Seige of Louisbourg Medals, 1758

During the summer of 1758, British and colonial forces captured the fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, which marked a turning point in the Seven Years’ War. Louisbourg was a strategically important stronghold that provided a safe harbor for the French navy and protected access to the St. Lawrence River, which was the outlet for the Great Lakes into the Atlantic Ocean and the critical waterway connecting the colonies of New France to the outside world.

The war originated in an ongoing and complex struggle over control of the Ohio River Valley between varied local agents (colonists, soldiers, missionaries, traders, etc.) representing Britain and France and the assorted Indian tribes that either inhabited the region or exerted power there. The flashpoint occurred in the course of competing efforts to establish a fort at the so-called “Forks” where the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers met. In the spring of 1754, French forces arrived at the Forks, knocked down a small British fort that had been established there, and built Fort Duquesne. In retaliation, a company of colonial militia under the command of the young Lieutenant Colonel George Washington and some Indian allies ambushed a French patrol in late May. This seemingly minor but bloody skirmish kicked off a conflict that lasted almost a decade and spanned the globe.

While the ins and outs of the war are invariably interesting, the most important thing to understand in the context of the North American theater was that things did not go particularly well for Britain and its colonial proxies during the early years of the conflict. This string of setbacks and defeats culminated in the summer of 1757 with the loss of Fort William Henry at the southern edge of Lake George and a failed expedition to capture Louisbourg. These failures led to wholesale changes in the British military leadership and saw the energetic William Pitt emerge to direct the overall war effort. Because Louisbourg played such a key role in protecting the lines of supply that sustained French forces, it became the primary target of Pitt’s ambitious strategy for the 1758 campaign in North America.

Major General Jeffrey Amherst and Admiral Edward Boscawen were placed in charge of the land and naval forces, which ultimately comprised some 14,000 soldiers and 200 ships, including twenty-three ships of the line. The prior year’s expedition failed in part because the French navy was able to concentrate enough warships at Louisbourg to make a direct assault on the fortress difficult, but by 1758 it no longer had that capability. The tightening of the blockade of French ports by the Royal Navy made resupply challenging, and the main relief fleet was destroyed at the Battle of Cartagena in February. A sally from the main French Navy port at Brest was likewise turned back in April, leaving the defenders at Louisbourg with just five ships of the line and no hope of resupply for the summer.

Despite a brief but determined resistance from entrenched defenders at Gabarus Bay, British troops were landed on June 8 and the formal siège une forme commenced. Vauban’s famed treatise De l’attaque et de la défense des places (“On the Attack and Defense of Fortified Places”) laid out a strategy for overcoming the defenses at Louisbourg that Amherst followed to the letter.

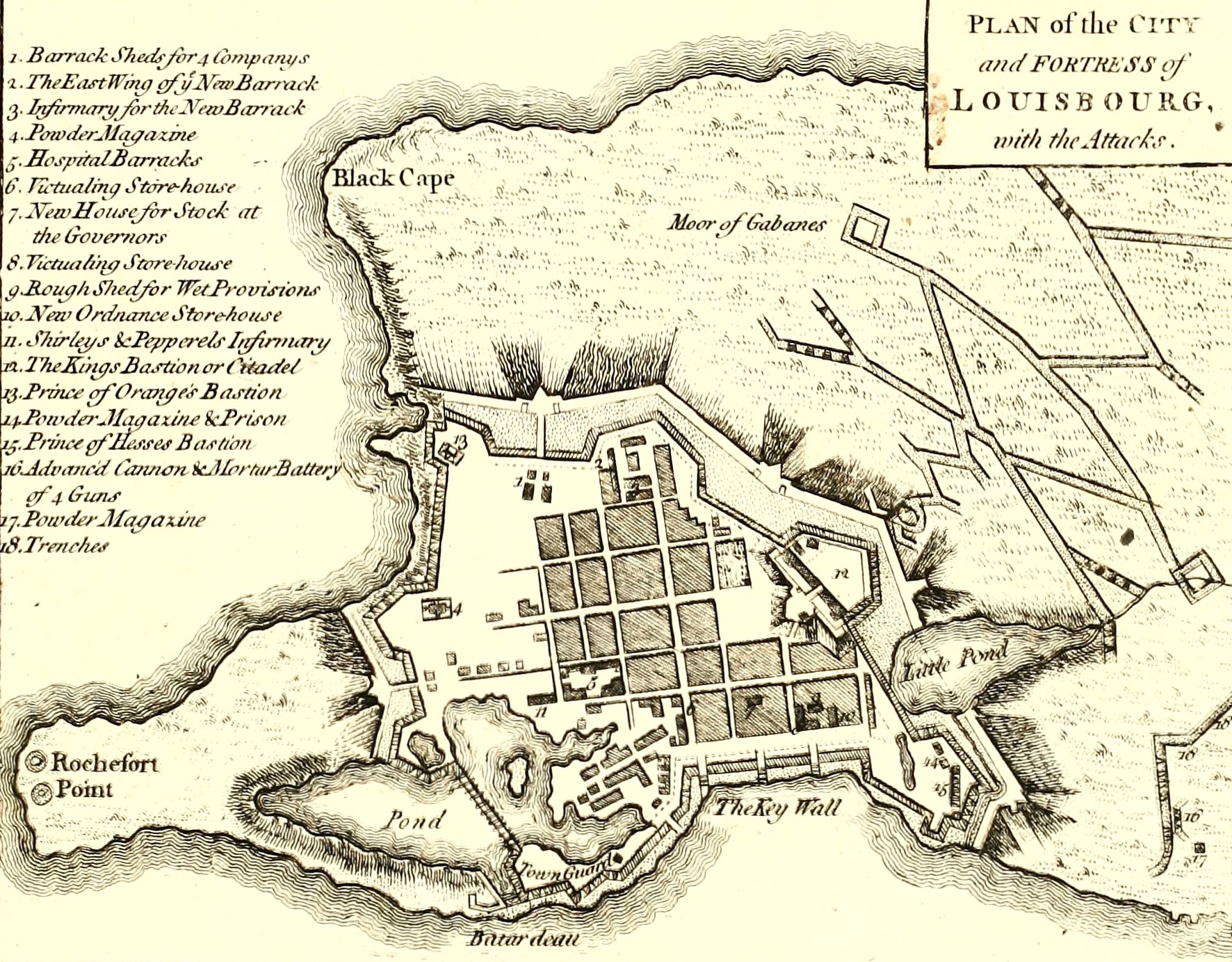

The illustration above shows the impressive landward defenses and bastions of the fortress, as well as the network of trenches dug by its attackers. The comparatively vulnerable fortifications facing the harbor were buttressed by the French warships, which rode at anchor just offshore and prevented Admiral Boscawen’s fleet from forcing an entrance into the harbor. Still, with any kind of relief made impossible by the Royal Navy, it was only a matter of time before the fortress fell. The British soldiers set to work digging, slowly hauled their cannon forward, and soon began shelling the French into submission. By July 6, the attackers were within 600 yards of the walls and red hot cannon shots were raining on the city. Six-weeks of constant shelling, mounting casualties, and frequent fires taxed Louisbourg’s defenders to the breaking point. Boscawen’s marines delivered the coup de grâce on July 25, sneaking into the harbor under the cover of fog and burning or capturing the remaining French warships.

Toronto Public Library

With the city now surrounded and the shelling set to intensify, the chevalier de Drucour surrendered Louisbourg the next day. Although generous terms might have been expected given the precepts of contemporary warfare and the vigorous defense mounted, Amherst was unforgiving. Honors were denied to the garrison, and all who bore arms were made prisoners of war and transported to England. The entire civilian population of Cape Breton was deported back to France and many of the Indians allied with the French, primarily Micmacs and Abenakis, were slaughtered by British soldiers and American rangers in revenge for the massacre that followed the surrender of Fort William Henry in 1757.

The Siege of Louisbourg was a brutal and decisive victory that paved the way for the successful invasion of Canada and the larger Annus Mirabalis of 1759 that left France and its allies reeling. Its capture and the humiliating terms of the defeat were quickly commemorated in medallic form. At least in terms of the numismatic legacy of the siege, it was Boscawen, not Amherst, who figures much more prominently, despite the latter’s ostensibly more significant role in the fall of the fortress. In C. Wyllys Betts’ catalog of American colonial medals, Boscawen is listed as gracing eight of the twelve Louisbourg medals. The medal above depicts and celebrates the moment of French capitulation, and its obverse features a bust wreathed with the legend: TO BRAVE ADM. BOSCAWEN

A number of medals feature the same rather crudely executed bust of Boscawen on the obverse. The most interesting of the varied reverses depicts the scene in Louisbourg harbor on July 26, 1758. By far the most notable and elaborate medal in the series was one Boscawen commissioned from the distinguished medallist Thomas Pingo (1692-1776).

The medal was struck in gold, silver, and copper. The ANS holds examples of each, but the gold specimen (ex-Norweb) is the prize as it is supposed to have been Boscawen’s own, with the few other gold medals having been awarded to trusted officers. It is a masterpiece of medallic propaganda that depicts a prostrate female figure in the foreground seemingly being crushed by a globe and forlornly pointing at a falling fleur-de-lis. Standing triumphantly above her are a soldier and a sailor with the legend PARITER IN BELLA (“equally brave in war”) stretching between them. Above, Fame holds a laurel wreath in one hand and blows on a trumpet, announcing the British victory to the world.

The reverse shows the events of July 25, when Boscawen’s sailors burned the Prudent and stole the Bienfaisant in a daring raid. This well-engraved scene shows the ships of the Royal Navy preparing to enter the harbor in the background while a British battery shells the fortified town in the foreground. One of the remarkable details is the dotted line of a cannon shot that tracks across the face of the medal from the lower left corner to the ball just bellow the V in the date (click to enlarge). As the plethora of Louisbourg medals held by the ANS suggests, it marked a significant turning point in the Seven Years’ War.

British engineers systemically destroyed Louisbourg’s fortifications after the battle, but a garrison was maintained at the site until 1768. The present-day town of Louisbourg is located on the north side of the harbor, some distance away from the original fortress to its southwest. The historical town and fortress was the subject of a fascinating government-sponsored research and reconstruction project in the 1960s and 1970s. The site today stands as a wonderful example of effective cultural and heritage work, and it is well worth a visit if you are in the area.

Those wishing to learn more about the history of Louisbourg and the larger conflict in which it played such a pivotal role are in luck! Christopher Moore’s masterful Louisbourg Portraits (1982) follows the varied experiences of an accused thief, a young bride, and a Swiss mercenary, among others, to give readers a vivid impression of what life was like in the eighteenth-century French outpost. Fred Anderson’s Crucible of War (2000) focuses on the participation and perspective of British North American colonists in the conflict and highlights how the legacy of the war led to the Revolution. It is quite simply one of the best history books published in recent years.