Scythian–Greek Relations in the North and Northwestern Black Sea Area (Sixth–Fifth Centuries BC): Numismatic Evidence

This blog post reproduces Elena Stolyarik’s chapter in Essays on Ancient Coinage, History, and Archaeology in Honor of William E. Metcalf (Numismatic Studies 38), edited by Nathan T. Elkins and Jane DeRose Evans, ISBN 978-0-89722-357-7, published by the ANS in 2018.

The migration of the Scythians, an Iranian-speaking group of nomads from Central Asia, to the North Pontic territory, today’s Russian and Ukrainian steppes, was one of the most important phenomena of the ancient oikoumene. Through military conflicts, cultural and ethnic interactions, as well as trade, it forever changed the social landscape of the Greeks and other ethnicities in the region.

During the late seventh and the sixth centuries BC, numerous Greek colonies were established at the mouths of the major rivers of this North Pontic region. The settlements of Olbia, Tyra, Niconion, and Istria, among others, were built on the lower Dnieper (the ancient Borysthenes), Dniester (ancient Tyras) and Danube (ancient Ister) river regions, just a few miles away from where they merge with the Black Sea.

By the time Greek colonists first encountered the Scythian tribes, Greek cities were already using metal coinage, and early coins are frequently found along the areas of Greco-Scythian trade. Probably the earliest coin-like objects were made in the form of arrowheads (Fig. 1).

This arrowhead money, according to finds, circulated widely among the Scythians, Thracians, and Greeks of the northern Black Sea. Examples have been found at various ancient sites such as Olbia and Berezan, Nikonion, Apollonia Pontica, Istros, Tomis, and Odessos.[1] A variety of dates have been proposed for the manufacture and circulation of this coinage. At Istros and on Berezan Island, arrowhead money was found in the Archaic strata, along with fragments of imported ceramic ware.[2] At Olbia, a graffito on a black-glaze vessel that is dated to ca. 600 BC demonstrates that arrowhead money was used among the Olbiopolitans at that time.[3] It continued to be in circulation a century later, as demonstrated by the Burgas Hoard, a container filled with arrowhead money[4] and also by the finding at Nikonion of an arrowhead specimen in a complex alongside ceramic fragments of the fourth century BC.[5]

Some scholars argue that the arrowhead money was made in Thrace, because the Burgas hoard included a clay mold for casting them.[6] Other specialists assign them to the Scythians.[7] Finally, there are some scholars who reject any connection of these objects with the Black Sea tribes. They believe that the residents of the Greek towns of Apollonia, Istros, and Olbia issued this money, because the finds have been concentrated in their vicinity. The discovery near Olbia, at Berezan, of a small weight with a relief of an arrowhead coin, as well as lead arrowhead objects, supports this hypothesis.[8] Irrespective of who exactly made the arrowhead money, it is clear that these finds are concentrated in the contact area between the Scythian and Thracian tribes and the Greek colonies of the northwestern and western Black Sea littoral.

During the latter half of the sixth century BC, the arrowhead money is accompanied by another unusual type, cast bronze tokens in form of dolphins (Fig. 2). These “dolphins” were in circulation in the North Pontic area and have been found in the Dobrudja as well, where they were adopted and improved upon by the local tribes.[9] The issuance of these cast coins was presumably a halfway measure between the local tradition of circulating small cast bronze artifacts and the production of a proper coinage.[10]

From the very beginning, the Greek colonies on the Black Sea coast were entrepôts for trade with the indigenous population. The Olbian polis, for example, supplied wheat from the Black Sea hinterland to Attica, and at the same time developed trade contacts with its Scythian neighbors, to whom it supplied wine in amphorae, expensive bronze vessels, jewelry from Greece, and its own manufactured products.[11] Rapid economic development and the consequent demands of trade required a more sophisticated monetary system than that provided by the cast copper tokens of the sixth century BC.[12] Consequently, the domestic market of Olbia began to use full-value bronze obols and their fractions in the second quarter of the fifth century BC.[13] These cast coins, known as “asses,” spread to the territories that were subject to Olbia and in the contact zone with the Scythian tribes, but they did not immediately replace the arrowhead and dolphin money already in circulation, nor did they fulfill the need that a more sophisticated local economy had for a higher-value coinage (Fig. 3).

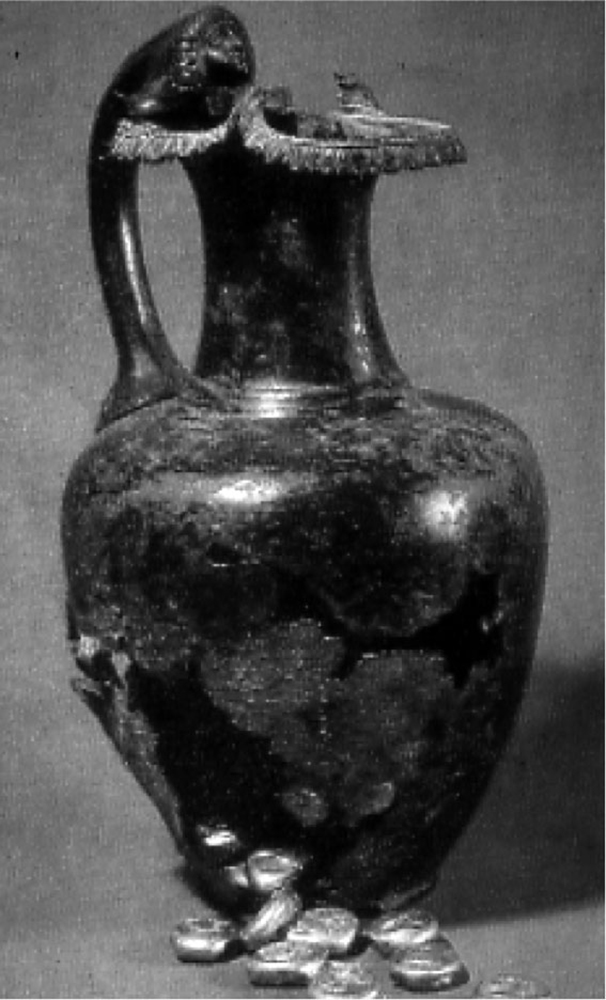

Money of high denomination was supplied by cyzicenes—the electrum coinage of Cyzicus in the form of staters and their smaller fractions, obtained in exchange for wheat exports. These coins provided the city markets with a resilient coinage in numerous denominations, which was at the same time accepted by the Greek cities as well as the Scythian and Thracian tribes of the Pontic area.[14] The second biggest hoard of cyzicenes ever discovered (the largest being the Prinkipo hoard, IGCH 1239, with over 200 examples) was found in 1967 in the lower Danube area in the village of Orlovka (IGCH 726), not far from modern Odessa. In ancient times, this location had Thracian and Scythian settlements and was associated with a commercial and military road that facilitated access across the Danube.[15] The hoard was composed of 74 cyzicenes stored in a bronze oinochoe dated to the second quarter of the fifth century BC (Fig. 4).

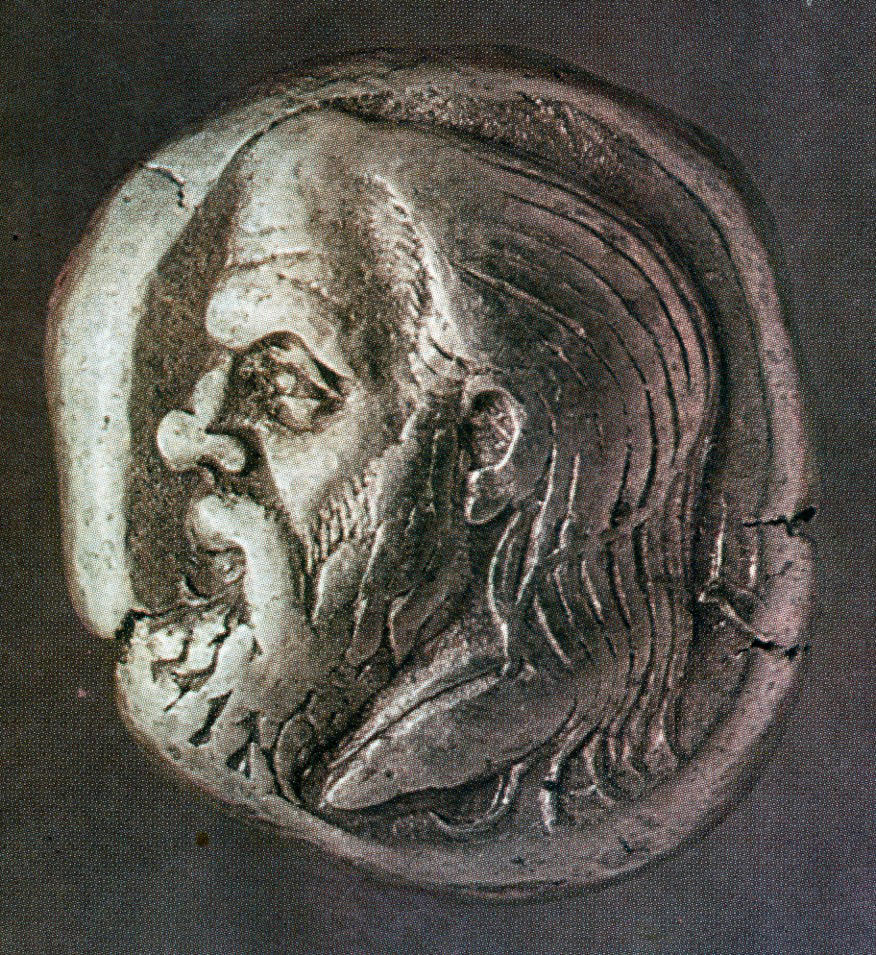

These coins, some of which were previously only known only from unique specimens, also provided several new, previously unrecorded types. Among these new types was a stater featuring the head of a bearded man (Fig. 5), which closely resembles the images of Scythians found on metalwork from the kurgans of the Black Sea Steppes (Fig. 6). [16]

The introduction of patently Scythian portraits on coinage suggests that people’s growing power. Scythian determination to rule the steppes had been noted in Herodotus’ legend about Heracles, which became entwined with local religious and epic traditions concerning a hero in whom the Scythians saw the progenitor of their race (4.8–10). In this myth, Herodotus tells us how Heracles arrived in Scythia with the herd of cattle stolen from Geryon. There, in the sacred place of the Olbiopolitans named Hylaia, he encountered Erchidna, a snake-legged local chthonic divinity. From the subsequent union of demi-god and monster, three sons were born. The myth further relates how Heracles said that the son who could draw his bow would inherit the Scythian lands. “He took off one of his bows (hitherto he had carried two), and he showed the way in which the belt was put on” (4.10). Scythes, the youngest, was the only one who was able to draw Heracles’ bow, thereby proving himself to be the strongest, and so he inherited the land and the power. This mythological tale is recalled on the first Olbian silver coins, struck around 460–440 BC, bearing the legend EMINAKO and showing Heracles stringing his bow (Fig. 7).[17]

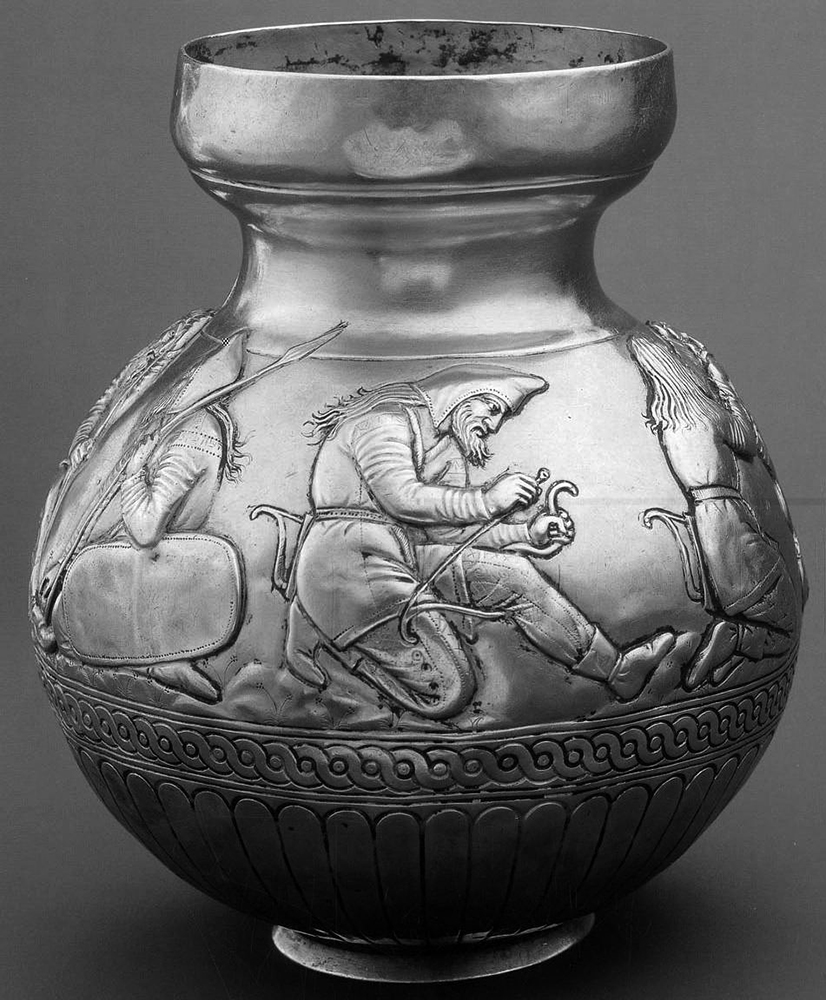

This myth also is reflected on the gold vase of the fourth century BC, from the Kul-Oba kurgan, a famous Scythian barrow excavated in 1830 in eastern Crimea, modern Ukraine (Fig. 8).

Although the mythology behind the type is clear, the name EMINAKO has engendered a vigorous debate. Some hold that the coins show the dependence of Olbia upon the Scythians and that a ruler with the name EMINAKO—which is attested for some Scythian rulers—resided near Olbia. [18] Others argue that this image of Heracles shows him as a Greek hero with his usual attributes and that the name Eminakos could be an Olbiopolitan magistrate.[19] Another hypothesis suggests that the brief emission of these staters is to be associated with the rule of a tyrant in Olbia.[20] Whether the coin is a Scythian issue or an Olbiopolitan issue, it should be pointed out that these coins were in circulation in Olbia proper during the fifth century BC, which demonstrates that the Hellenes of Olbia were not distinct from nor hostile towards the religious and epic traditions of the autochthonous population. The mythology also reflects a positive relationship between Greek and non-Greek people through the conclusion of a sacred marriage between the famous Greek hero and the local snake goddess, an event epitomizing mixed marriages between Greeks and Scythians and a religious syncretism in their beliefs.[21]

At the beginning of the second quarter of the fifth century BC, the Scythians not only controlled the Pontic steppe regions but also held economic and political sway over the Greek cities.[22] Although some scholars have taken issue with the idea of a “Scythian protectorate,”[23] numismatic evidence shows that the Scythian king Scyles (470–450 BC), the son of King Ariapeithes, exercised control over the lower Dniester basin. In this period Scyles began to issue his own bronze cast coinage in the city of Nikonion, with the image of an owl and his own name, ΣΚ, ΣΚΥ or ΣΚΥΛ (Figs. 9–10).[24]

Nikonion, founded in the second half of the sixth century BC on the eastern shore of the Dniester (ancient Tyras) estuary[25] together with Tyra (another important Ionian colony on the western edge of the Dniester Liman) played a key role in the trade and commerce of the Dniester-Danubian region.[26]

Scythian control may have also extended to Istros, a Milesian colony in the lower Danubian area.[27] Scyles was the son, after all, not only of the Scythian king Ariapeithes, but of a Greek mother from Istros (Herodotus 4.78). Numerous finds of Istros’ cast coins with the wheel device at Nikonion and the lower Dniester basin[28] may be offered as support for the hypothesis that Nikonion was in fact a colony of Istros.[29]

The use of the owl, a quintessential Athenian image, on the coins of Scyles surely indicates the importance of Athens in the Black Sea region after the Athenians’ decisive victories over the Persians in 490 and 480/79 BC, when imports from Athens increased in the northern Black Sea region. Athenian influence in the North Pontic area grew still further after Pericles’ expedition into the Pontus in 437 BC. Olbia, Tyra, Nikonion, and Istros were included in the Athenian maritime league.[30] This influence was possible because the Scythians’ control over the Greek colonies was weakening. Increasing sedentism disrupted the traditional nomadic social system and weakened Scythian military power in the last quarter of the fifth century BC. The growth of the nomad population and limited territory led to active foreign expansion.

In the first half of the fourth century BC, an independent group of Scythians under King Ateas crossed the mouth of the Danude delta and invaded the Dobrudja (the territory situated between the lower Danube and the Western Black Sea region). This event marks a new chapter in the history of Scythian relations with the Greek colonies of the Western part of the Black sea littoral. By this time the old token currencies and the early mythological references to Scythian foundations were all abandoned, and new, up-and-coming rulers seeking to consolidate their power struck a variety of emissions bearing their names and likenesses, following traditions well established by the neighboring Greek cities.

Bibliography

Alekseev, V. P. and P. Loboda. 2002. “Neizdannye i redkie monety Nikoniya i Tiry.” Vestnik Odesskogo Muzeya Numizmatiki 13: 6–8.

Anokhin, V. A. 1986. “Moneti strelki.” In Ol’viya i ee okruga, ed. A. S. Rusyaeva, 68–89. Kiev: Naukova Dumka.

______. 1989. Moneti Antichnikh Gorodov Severo-Zapadnogo Prichernomor’ya. Kiev: Naukova Dumka.

Aricescu, A.1975. “Tezaurul de semne de schimb premonetare de la Enisala.” Studii si cercetari de numismatica 6: 23.

Avram A. 2003. Histria. Ancient Greek Colonies in the Black Sea Vol. I. Thessaloniki: The Archaeological Institute of Northern Greece.

Avram, A., J. Hind, and G. Tsetskhladze. 2004.”The Black Sea Area.” In An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis. An Investigation Conducted by the Copenhagen Polis Centre for the Danish National Research Foundation. M. Hansen and T. H. Nielsen (eds.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. 924–73.

Balabanov, P. 1986. “Novi izsledovaniya v rstrelite-pari,” Numizmatika. 20/2: 3–14.

Bruyako, I. 2013. “Kultury Getov.” In Drevnie Kultury Severo-Zapadnogo Prichernomor’ya, 429–43. Odessa: SMIL.

Bulatovich, S. A.1970a. “Klad kizikinov iz Ol’vii.” Sovetskaya Arkheologiya 2: 222–24.

______. 1970b. “Klad kizikinov iz Orlovki.” Vestnik Drevnei Istorii 2: 73-86.

______. 1976. “Obraschenie elektrovih monet Maloy Azii v Egeiskom Basseine i v Prichernomor’e.” Materiali po Arkheologii Severnogo Prichernomop’ya 8: 95–108.

______. 1979. “Nova znakhidka moneti Kizika.” Arkheologia 29: 95–98.

Dimitrov, B. 1975. “Za strelite-pari ot Zapadnogo i Severnoto Chermorsko kraibrejie.” Arkheologia 2: 43–48.

Gerasimov, T. 1939. “S’krovische ot bronzobi streli-moneti.” Izvestija na Balgarskoto Arheologiceskija Druzestvo Institut 12: 424–27.

______. 1959. “Domon.etni na pari u trakiiskogo pleme acti.” Arkheologia 1/2: 86–87.

Grakov, B. N.1968. “Legenda o skipfskon tsare Ariante.” Istoriya, arkheologiya i etnographia Srednei Azii. Moskva. Nauka: 101–15.

______. 1971. “Esche raz o monetah-strelkakh.” Vestnik Drevnei IstoriiI 3:125–27.

Karyshkovskiy, P. O.1960. “O monetakh s nadpis’yu EMINAKO.” Sovetskaya Arkheologia 1:179–95.

———. 1984. “Novie materiali o monetakh Eminaka.” Ranniy jelezniy vek Severo-Zapadnogo Prichernomor’ya, (Kiev): 78–89.

______. 1987. “Monety skifskogo tsarya Skila.” Kimmeritsy I Skiphy. Tezisy dokladov vsesoyznogo seminara posvyaschennogo pamyti A. I. Terenozkina. Kirovograd: 66–68.

______. 1988. Moneti Ol’vii. Kiev: Naukova Dumka.

Karyshkovskiy, P. O. and I. B. Kleiman. 1985. Drevnii gorod Tira. Kiev: Naukova Dumka.

______. 1994. The City of Tyras. Odessa: Polis Press.

Kryzhitskiy, S. D. 2001. “Olviya I Skifi u Vst. do n.e. Do pitannya pro Scifskii ‘Protektorat.’” Arkheologia 1: 21–35.

______. 2005. “Olbia and the Scythian in the Fifth Century B.C. The Scythian Protectorate.” In David Braund (ed.) Scythian and Greeks: cultural interactions in Scythia, Athens and the early Roman Empire (sixth century BC – first century AD. Exeter University of Exeter Press: 123–30.

Kryzhytskiy, S. D., V. V. Kapivina, N. A. Lejpunskaja, and V. V. Nazarov. 2003. “Olbia-Berezan.” Ancient Greek Colonies in the Black Sea, vol. I. Thessaloniki: Archaeological Institute of Northern Greece. 389–651.

Laloux, M. 1971. “La circulation des monnaies d’electrum de Cyzique.” Revue Belge de Numismatique11: 31–69.

Lapin, V. V. 1966. Grechiskaya kolonizatsiya Severnogo Privernomor’ya. Kiev.

Leypunskaya, N. A. and B. I. Nazarchuk.1993. “Nova znahidka moneti Eminaka”. Arkheologia 1: 115–20.

Marchenko, K. K. 1993. “K voprosy o protectorate skiphov v Severo-Zapadnom Prichernomor’e V v. do n.e.” Peterburgskiy arkheologicheskiy vestnik 7: 43–47.

______. 1999. “K probleme greko-varvarskikh Kontaktov v Severo-Zapadnom Prichernomop’e V-IV vv. do n.e.(sel’skie poseleniya Nijnego Pobuj’ya).” Stratum plus, High Anthropological School 3: 145–72.

Mielczarek, M. 1999. “Monety obce i miejscowe w greckim Nikonion.” Wiadomosci Numizmatyczne 43,1–2: 12.

______. 2005. “Coinage of Nikonion. Greek Bronze Cast Coins between Istrus and Olbia.” XIII Congreso Internacional de Numismática. Madrid-2003. Actas-proceeding- Actes. Madrid: 273–76.

______. 2012. “On the coin circulation and coin hoards in Greek Nikonion.”

I ritrovamenti monetali e i procesi storico-economici nel mondo antico. Padova: 79-86.

Okhotnikov, S. B.1990. Nizhneye Podnestrov’ye v VI-V vv. do n.e. Kiev: Naukova Dumka.

______. 1995. “Prostranstvennoe razvitie i kontakti polisov Nijnego Podnestrov’ya (VI-III v.v. do n.e.).” In Antichnie polisi i mestnoe naselenie Prichernomor’ya. Materilai Mezhdunarodnoi Nauchnoi Konferentsii Sevastopol: 120–24.

______. 1997. “Phenomen Nikoniya.” In Nikoniy I antichnyi mir Severnogo Prichernomor’ya, 27–32. Ed. By S. B. Okhotnikov. Odessa:Vetakom.

______. 2006. “The Chorai of the Ancient Cities in the Lower Dniester Area (6th century BC–3rd century AD).” Surveying the Greek Chora: The Black Sea Region in a Comparative Perspective. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. 81–98.

Oreshnikov, A. V. 1921. “Etyudi po numizmatike Chernomorskogo poberej’yaI.” Izvestiya Rossiyskoy Akademii Istorii Material’noy Kul’turi 1/1: 225.

Pippidi, D. M. and D. Berciu. 1965. Geţi şi greci la Dunărea de jos. Bucureşti: Editura Academiei republicii populare Române.

Preda, F. 1961. “Virfuri de săgeţi cu valoare monetară.” Analete universitaţii. C. I. Parhon, Bucureşti, Ser. Stiinţe Sociale şi Istorice 9/16: 11, 13–14.

Preda, C. “In legatura cu curculatia staterilor din Cyzic la Dunarea de jos.”

Pontica 7: 139–46.

Rayevskiy, D. S. 1977. Studies in the Ideology of the Scythian-Sakian Tribes.

Moscow: Nauka. [in Russian].

Rusyaeva, A. S.1979. Agricultural Cults in Olbia in the Pre-Getan Period. Kiev: Naykova Dumka. [in Russian].

______. 2007. “Religious Interactions between Olbia and Scythia.” In Classical Olbia and the Scythian World: from the sixth century BC to the

second century AD, pp. 93–102. D. Braund and S. D. Kryzhitskiy (eds.). Proceedings of the British Academy 142. Oxford: British Academy.

Samoylova, T. L.1988. Tira v VI-I vv. do n.e. Kiev: Naukova Dumka.

Severiano, G. 1926. “Sur les monnaies primitives des scythes.” Buletinul SNR 21, no. 57/58: 4–6.

Snitko, I. A. 2011. “Ol’viyckaya Tiraniya, Skifskii Protektorat i nekotorie voprosi sotsial’no-politicheskoi i ekonomicheskoy istorii Olviyskogo polisa pozdhearhaicheskogo i ranneklassicheskogo vremeni.” Materiali po Arheologii Severnogo Prichernomor’ya 12:125–49.

Sekerskaya, N. M. 1989. Antichniy Nikoniy i ego okruga v VI- IV vv. do n.e. Kiev: Naukova Dumka.

______. 1995. “Nizhnee Podnestrove i Afiny v period pentekontii. Tezisi dokladov mezhdunarodnoi konferencii.” Problemy Skifo- Sarmatskoi Arkheologii Severnogo Prichernomor’ya”, Zaporozhe: 170.

______. 2001. “Nikonion.” North Pontic Archaeology. Recent Discoveries and Studies, Colloquia Pontica 6, pp. 68–90. Gocha R. Tsetskhladze (ed.). Leiden: Brill.

Sekerskaya, N. M. and S. A. Bulatovich. 2010. “Monetnie nakhodki iz Nikoniya (1964–2010).” Zapiski otdela numismatiki i torevtiki Odesskogo Arkheologicheskogo Muzeya. V. I. Odessa: SMIL: 27–38.

Talmaţchi, G. 2007. The mints’ issues from the Black Sea coast and other areas

of Dobrudja. The pre-Roman and early Roman periods (6th century BC–1st century AD). Coins from Roman sites and collections of Roman coins from Romania XI. Cluj-Napoca: Mega Editura.

______. 2010. SEMNE MONETARE din aria de vest si nord-vest a Pontului Euxin. De la symbol la comert (secolele VI-V a. Chr.). MONETARY SIGNS in the West and North-West Are4a of Pontus Euxinus. From Symbol to Trade (6th–5th Centuries B.C.). Cluj Napoca: Mega Publishing House.

Vinogradov, Yu.G. 1980. Persten’ tsarya Skila: politicheskaya i dinasticheskaya istoriya skifov pervoi poloviny 5 veka do n.e. Sovetskaya Arheologiya 3: 92–109.

______. 1989. Politicheskaya istoriya Ol’viiskogo Polisa. VII-I vv. do n.e. Istoriko epigraphicheskoe issledovanie. Moscow: Nauka.

______. 1997. Pontische Studien. Kleine Schriften zur Geschichte und Epigraphik des Schwarzmeerraumes. Mainz: von Zabern.

Vinogradov Ju.G. and S. D. Kryzitckij.1995. Olbia. Eine altgriechische Stadt im nordwestern Schwarzmeerraum. Leiden: Brill.

Zaginailo, A. G. 1966. “Monetnie nahodki na Rokcolanskom gorodische (1957–1963 gg.).” Materiali po Arkheologii Severnogo Prichernomor’ya 5: 100–30.

______. 1982. “Kamenskiy klad strelovidnikh litih-monet.” In Numizmatika Antichnogo Prichernomor’ya, 20–26. Kiev: Naukova Dumka.

Zaginaylo, A. G. and P. O. Karyshkovskiy.1990. “Monety skifskovo tsarya Skila.” In Numizmaticheskie issledovaniya po istorii yugo-vostochnoy Evropi, pp. 3–15. Kishinev: Shtiintsa.

Zlatkovskaya, T. V.1971. Vozniknovenie gosudarstva u Frakiitsev. Moscow: Izd-vo Nauka.

[1] Zaginailo: 1966, 111–12; Dimitrov 1975: 43–48; Zaginailo 1982: 20–28; Anokhin:1986, 68–89; Balabanov 1986: 11; note 28; Karyshkovskiy 1988: 30–33; Talmatchi: 2010).

[2] Preda 1961: 11, 13–14; Pippidi and Berciu 1965: 192; Lapin 1966: 144–46; Aricescu 1975: 23.

[3] Grakov 1968: 101–15: Grakov 1971: 125–27.

[4] Gerasimov 1939: 424, 427, obr. 210.

[5] Zaginailo 1966;111–12.

[6] Gerasimov 1939: 424, 425; Gerasimov 1959: 85.

[7] Severiano 1926: 4–6; Pippidi and Berciu: 1965, 109–10; Zlatkovskaya 1971: 65–66.

[8] Lapin 1966: 145; Grakov 1971: 125–26.

[9] Karyshkovskiy 1988: 34–40; Talmatchi 2010: 118.

[10] Karyshkovskiy 1988: 33; Karyshkovskiy 2003: 383.

[11] Vinogradov, Kryziciskij 1995.

[12] Kryzhytskiy 2003: 401.

[13] Karyshkovskiy 1988; 42–49.

[14] Bulatovich 1970a: 222–24; Laloux 1971: 31–69; Preda 1974: 139–46; Mielczarek 1999: 12; Alekseev, Loboda 2002: 6–8; Alekseev, Loboda 2003: 273; Alekseev, Loboda 2012: 83; Talmaţchi 2007: 28–29.

[15] Bruyako 2013: 416, 430.

[16] Bulatovich 1970b: 73–86; Bulatovich 1976: 95–108; Bulatovich 1979: 95–98.

[17] Karyshkovskiy 1984: 78–89; Karyshkovskiy 1988: 49–52; Leypunskaya, Nazarchuk 1993: 115–20.

[18] Karyshkovskiy 1960: 179–82; Karyshkovskiy 1984: 78–89; Rayevsky 1977: 166–71; Vinogradov 1989: 93–94.

[19] Oreshnikov 1921: 225; Rusyayeva 1979: 141–42; 2007: 98; Anokhin 1989: 15–16; Kryzhitskiy 2001: 21–35.

[20] Snitko 2011: 125–49.

[21] Rusyayeva 2007: 96.

[22] Vinogradov 1980: 108; Vinogradov 1989: 90–109; Marchenko 1999: 155.

[23] Kryzhitskiy 2001: 21–35; Kryzhitskiy 2005: 123–30.

[24] Karyshkovskiy 1987: 66–68; Zaginailo, Karyshkovskiy 1990: 3–15; Mielczarek 2005: 274–75; Sekerskaya, Bulatovish 2010: 30, Pl. 2, 11–13; Mielczarek 2012: 83.

[25] Sekerskaya 1989: Sekerskaya 2001; Okhotnikov 1990; Okhotnikov 2006.

[26] Karyshkovskiy, Kleiman 1985; Samoilova 1988.

[27] Marchenko 1993: 43–47.

[28] Sekerskaya 1989: 92, Sekerskaya 2001; Okhontnikov 1995: 121–22; Vinogradov 1997: 35, 229; Avram, Hindi and Tsetskhladze, 2004: 936.

[29] Ohotnokov 1997: 29; Avram 2003.

[30] Karyshkovskiy, Kleiman 1994: 91–93; Sekerskay 1995: 170; Vinogradov, Kryzickij 1995.