Local Coinages in a Roman World is at the printer!

For the fact that the Romans did not export their own coinage into the Greek world does not mean that their presence had no effect on existing monetary patterns.

M. Crawford, Coinage and money under the Roman Republic, 119

Over the course of the second and first centuries BC, Rome conquered most of the Mediterranean world in a whirlwind of military campaigns (Fig. 1). The lavish triumphal parades celebrated by Roman generals after their victories leave no doubt that Rome financially benefited from these victories and acquired an enormous quantity of bullion and foreign coinage on those occasions.

Joseph Mallord William Turner, The Decline of the Carthaginian Empire, exhibited 1817. Tate N00499, CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0.

However, despite the unrivaled military power achieved in the course of the second and first centuries BC, one of the most surprising factors in the development of Roman domination of the Mediterranean world is that the Romans conquered and ruled most of it without imposing their own coinage on the conquered. In their pragmatic attitude to imperialism, the Romans typically retained any form of effective organization as they acquired new territories.

It is thus all the more important to research how local coinages converged—at least partly—to create compatible monetary systems across the Roman Empire. The Roman Provincial Coinage (RPC) series offers an incomparable tool for studying the coinages issued in the Roman provinces and client-kingdoms from the age of the civil wars onward. However, this series does not include the coinages issued in the Roman provinces in the second century and in the first half of the first century BC, when most of the Mediterranean regions came under Roman dominion or established commercial relationships with the Roman power.

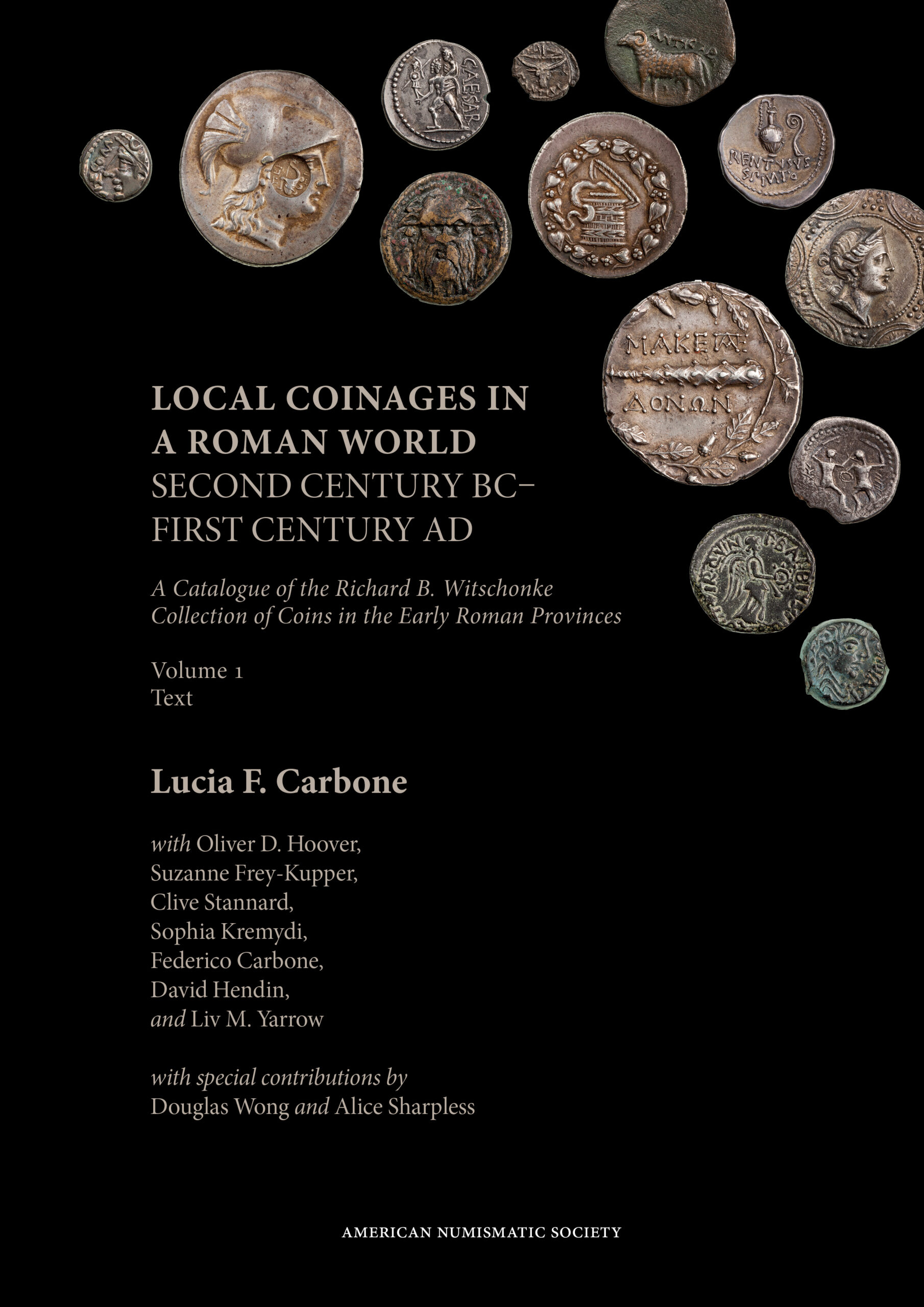

Figure 2. Cover of Local Coinages in a Roman World Vol. 1.

Local Coinages in a Roman World. The Catalogue of the Richard B. Witschonke Collection of Coins in the Early Roman Provinces (Fig. 2), now at the printer, represents a sort of “RPC Zero,” the historical and numismatic prologue to the study of Roman provincial coinage, as it addresses the coinage issued in the provinces of the Roman Empire in the second and first centuries BC.

Figure 3. ANS 2015.20.1924. A sestertius of L. Calpurnius Bibulus.

Figure 4. ANS 2015.20.1769. A cistophoric tetradrachm from Tralles with initials of Macedonian months.

The 3,726 coins included in this catalogue are all part of the Richard B. Witschonke Collection, acquired by the American Numismatic Society in 2015. Most of the specimens are of great historical and numismatic value, as argued in the historical introductions preceding each of the 36 sections of this catalogue. The 36 sections of the catalogue, encompassing the Mediterranean basin from West to East, adopt a progressive numbering comparable to the one adopted in RPC. The reason for adopting this progressive numbering is, again, the underlying idea that despite their diversity in media, types, and denominations, all the coinages included in the catalogue represent an answer to the shared need to operate in a world controlled by the Romans. Rather than providing only an overview of the monetary production in a specific area, each section is organized around a research question always related to changes brought in by Roman dominion to the monetary systems of the conquered areas.

Figure 5. ANS 2015.20.3238. Æ as, second half of second century BC. Ripollès and Gozalbes 2016, Group A2, no. 2a (A2-R2). 32.5 mm, 32.43 g; 9:00.

Fig. 6. ANS 2015.20.2393. Denarius Imitating RRC 302/1. Overstruck on a drachm of Illyrian Apollonia (SNG Copenhagen 387). Part of the name of the signers [API]ΣΤΩΝ and [AΠΟΛΛΟ]ΝΟΣ are visible, respectively, on the obverse and on the reverse of the host coin.

Figure 7. ANS 2015.20.2519. Eraviscan denarius imitating the reverse type of P. Crepusius (RRC 361/1) with the name of the chieftain DVTETI.

The typological (rather than geographical) criteria adopted in some sections of this catalogue represent a major difference from the organizational criteria adopted in RPC. This is the case for the sections dedicated to the so-called “fleet coinage” of Mark Antony’s praefecti classis (Section 15; Fig. 3) and to cistophori (Sections 23–27; Fig. 4). The sheer number of specimens of these series included in this catalogue certainly played a role, but historical questions related to these series and their function were the main reason for singling out these series. For example, the “fleet coinage” was issued by three different magistrates at different mints, but the whole coinage probably addressed the same function, i.e., the need for small change compatible with the Roman denominational system in the eastern provinces. For what concerns cistophoric coinage, which alone represents one-fifth of the collection, the historical importance of its chronological development from one of the silver coinages of the Attalid kingdom to the provincial coinage of the province of Asia could be addressed only if treated separately from the rest of the coinage issued in that region. While building on previous publications, Spanish, Geto-Dacian, and Eraviscan imitations of Roman coinage are organically addressed for the first time here (Sections 10 and 11; Figs. 5–7).

Figure 8. ANS 2015.20.2032. Minturnae. Æ sextans, ca. 214–212 BC. Stannard 2021, 268, fig. 4.8 (this coin). Overstruck on a Neapolis coin, early third century BC.

Figure 9. ANS 2015.20.3129. Æ unit, Por(cius), ca. 190/170–150/140 BC. Bahrfeldt 1904, no. 1; Calciati I, 341, no. 67; Frey-Kupper 2013, no. 182.

Figure 10. ANS 2015.20.2196. An Aesillas tetradrachm struck over a “Thasian style” tetradrachm.

While most of the sections are authored by Lucia Carbone, scholars of international acclaim contributed to specific sections, offering ground-breaking insights on previously understudied coinages. In Section 6, dedicated to “Non-State Coinages of Central Italy,” Clive Stannard offers a new chronological and typological organization for the complex materials encompassing imitative and special-purpose coinages issued in the region (Fig. 8). In Section 9, Suzanne Frey-Kupper hugely revises the chronology for the Romano-Sicilian coinage, showing how Roman quaestores were signing these coinages in the early second century BC (Fig. 9). Sophia Kremydi (Section 16) provides an updated overview of the coinage produced in Roman Macedonia right after the defeat of Perseus, the last of the Antigonids, in Pydna in 168 BC (Fig. 10). Oliver Hoover (Sections 20, 30–36) addresses the coinages issued in Bithynia, Cappadocia, Cilicia, Syria, Coele Syria, Judaea, and Egypt and discusses the most updated bibliography on this subject (Fig. 11). Moreover, Federico Carbone (Sections 7 and 13), Liv M. Yarrow (Section 4), and Oliver Hoover (Sections 28 and 29) wrote introductions for specific sections. Together with Lucia Carbone and Oliver Hoover, David Hendin contributed to the catalogue of the Decapolis, Idumaea, and Judaea (Section 35; Fig. 12).

Figure 11. ANS 2015.20.2844. Philip II Barypous. Silver tetradrachm, Antioch on the Orontes, ca. 57/6 BC. A previously unknown exergue control mark.

Figure 12. ANS 2015.20.3614. Uncertain Decapolis or Ituraea. Æ, Roman (Pompeian) era year 1 (64/3 BC). HGC 10, no. 381; Spijkerman 1978, 128–129, no. 1; Sofaer 11. 18.4 mm, 6.81 g; 1:00.

In sum, this catalogue aims at shedding light on the bilateral (yet unequal) relationships between Rome and its provinces in the formative second and first centuries BC. With this goal in mind, the study of the coinage issued in Rome has been integrated with the study of the coinage produced in the Roman provinces to assess the impact of Roman imperialism on the monetary systems of the provinces of the Roman Empire and vice versa.