Lottery Mania in Colonial America

As Powerball mania sweeps the nation, I thought it would be interesting to explore the longer history of lotteries in America with a look back to the eighteenth century. For a run-down of the particulars about how they operated, Ainsworth Rand Spofford, who served as the official Librarian of the United States, wrote a useful introduction to the subject you can read here. By way of a short summary, the practice of holding lotteries to raise money for local governments and private entities was brought by English colonists to North America in the seventeenth century. The Third Virginia Charter of 1612 granted the Virginia Company of London a license to conduct yearly lotteries to raise funds for supplies for early colonists. Spofford goes on to note that the award for what seems to have been the first proper lottery to take place in colonial America in 1720 was rather unusually for a brick house in Philadelphia rather than a cash prize.

As an essentially speculative venture, lotteries bred a certain amount of attendant trouble as they were easy to manipulate and in some cases the holders simply neglected to have a drawing and made off with the money altogether. Abuses such as this led to a swath of legislation, but both private and public lotteries proliferated. The more reputable ventures were authorized by local governments and fronted by prominent citizens, frequently with the aim of funding some worthwhile public project. As Spofford notes, it was looked upon as a kind of “voluntary tax” for public works, with the added benefit for subscribers of potentially getting a windfall.

The Scheme of the Second Philadelphia Lottery (1748) published by Benjamin Franklin gives a good overview of how a contemporary public lottery operated. Numismatists will be interested to note that all of the values were enumerated in terms of “pieces of eight” as Spanish dollars were the dominant form of coin in circulation. The drawing was done by putting all of the numbers in a wheeled bin that could be spun during the drawing. The plan was to sell seventy-five thousand dollars worth of tickets while ultimately reserving twelve-and-a-half percent or $9,375 dollars for public use with the balance being awarded as prizes. Schemes such as these were so popular and innocuous that even churches held lotteries to raise funds for their endeavors.

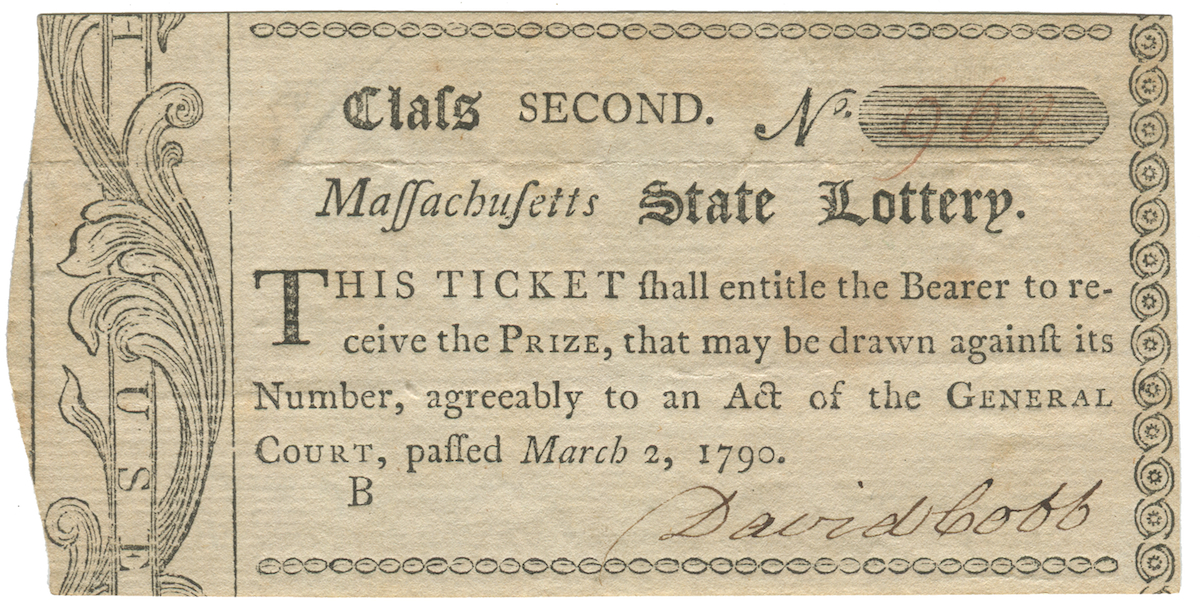

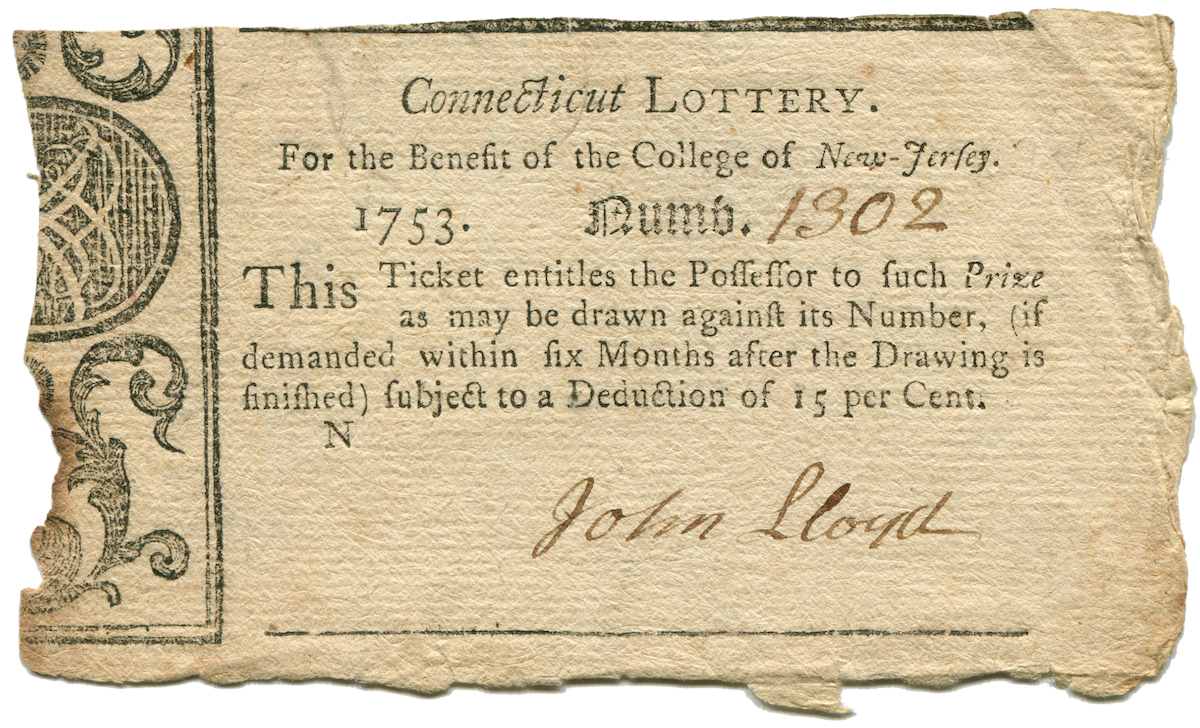

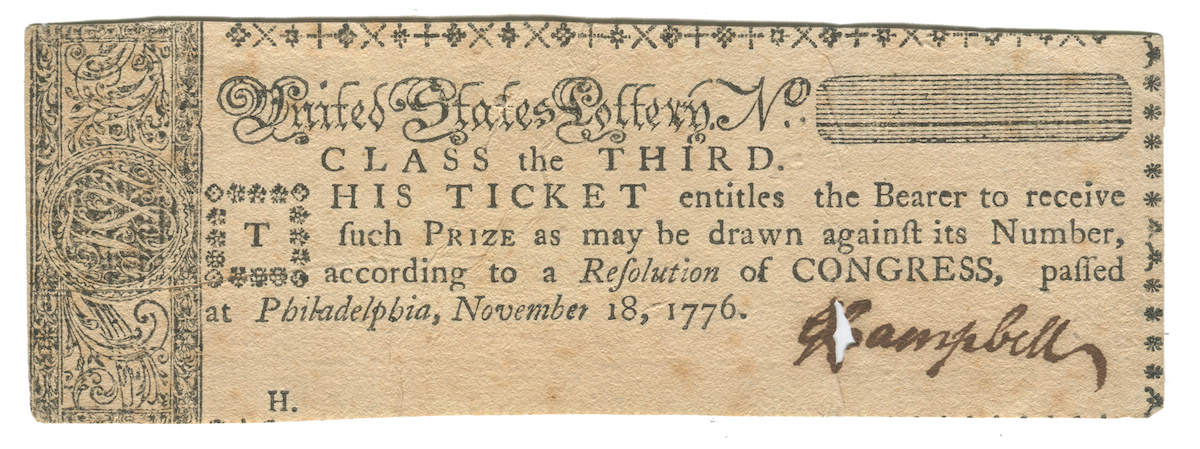

The American Numismatic Society holds about a dozen eighteenth-century lottery tickets. They are interesting in part for the numismatic and economic information they reveal, but also in terms of their design. Counterfeiters could easily manufacture a ‘winning’ lottery ticket because they were pen-numbered (and thus easily altered) and it took time for reports of the numbers to circulate and for winning tickets to be redeemed. Precautions needed be taken to prevent chicanery, which led to some innovative features.

The 1753 Connecticut lottery ticket above has a seemingly haphazard left edge because it was cut from a larger sheet. Anyone redeeming a winning ticket thus needed to have both the correct number and an edge matching the original sheet to validate its authenticity. Because the lottery was so much smaller, tickets were simply issued with consecutive numbers over the much more complex systems of today. Incidentally, this 1753 lottery was one of several held for the benefit of the “College of New Jersey,” i.e. Princeton University, and this particular one seems to have funded the construction of Nassau Hall.

Connecticut was a very active place for lotteries. In 1754 one was held to construct a wharf in New Haven. The ticket for that lottery at the ANS is particularly noteworthy because it seems to have been a winning ticket for the sum of £25. All in all, eighteenth-century lotteries were much more even in terms of dispersing winnings, with larger tiers of moderate payouts over what is more or less the winner-take-all format of today.

Arguably the most important lottery in American history was created by the Continental Congress in 1776 for “carrying on the present and most just and necessary war.” The “scheme” of the inaugural United States Lottery rather entertainingly refers to ticket holders as “adventurers.” Tickets were issued in different classes as the amount of awards and the cost of tickets escalated. This “Class the Third” ticket in the ANS collection was rather curiously signed but not seemingly issued as it lacks a number. Note the lines in the ‘No.’ field, which was meant to prevent alteration after a given ticket had a number written on it.

Just as the issuing and counterfeiting of Continental currency was part and parcel of the larger conflict, financing via lottery was another arena of contention. The ticket below was used as part of a Loyalist lottery held in British-occupied New York City in 1777 to raise money for the provisioning of British troops.

Although the rebellious colonists prevailed, the victory seemed to have done little to whet the public’s appetite for the lottery, and they proliferated in the United States during the late eighteenth century. A series of scandals in the nineteenth century, and the burgeoning of more or less fraudulent commercial lotteries hurt their reputation, but as today’s Powerball drawing suggests, the lottery still occupies a prominent place in American life and continues to play a significant role in funding public projects.