REDRESSING THE BALANCE, PART 1: THE GLORIES OF LEAD

Brasher dubloon (ANS 1969.62.1)

When thinking about the collection of the American Numismatic Society, the mind often leaps first to the trays of gold and silver coins, to beautiful and famous rarities, and the extremely valuable pieces that only a select few could ever hope to own privately. The shiny stuff has a great allure. There is no question about that. Who doesn’t like the warm glow of the Brasher doubloon or appreciate the rarity of the Confederate States silver half-dollar? I can personally attest to the great thrill of holding one of these in each hand while we were preparing the Drachmas, Doubloons, and Dollars exhibit for the Federal Reserve back in 2000.

Lead token of Boure, A., Canada (ANS 1966.176.492)

This edition of Pocket Change, however, is not about such pretty and valuable coins. Instead it is about the coins in the collection that many readers may not know about. They are the forgotten coins, the odd coins, the sometimes distrusted and maligned coins. They are those humble and unsung heroes of the ANS cabinet—the lead coins.

It may come as some surprise (perhaps even shock) to learn that the ANS collection includes some 4,448 lead pieces (including ancient scale weights, seal impressions, medals, and modern fakes). These range in place and period from Archaic Greece and Classical India to the Netherlands in the sixteenth century and the United States in the nineteenth century.

Samian lead hemistater (ANS 1979.116.1)

Lead coins of all periods generally fall into one of four main categories:

Counterfeits intended to deceive the unwary in commercial transactions. This use of lead can be traced in the Western World all the way back to the late sixth century BC, not long after coinage was invented. Herodotus reports a rumor that Polycrates, the tyrant of Samos, struck lead coins and plated them with gold (probably really electrum, an alloy of gold and silver) to buy off a besieging Spartan force in 525/4 BC. Despite the doubts of the Father of History, the ANS collection includes a Samian lead hemistater that tends to support the story as well as several Milesian lead issues of even earlier vintage (c. 560-545 BC). Although plated bronze cores seem to have been far more common than plated lead in later periods, lead counterfeits were still produced by unscrupulous individuals to pass as silver coins as late as the early twentieth century AD. The Society’s collection includes a number of lead U.S. half-dollars, quarters, and dimes that were cast from authentic silver examples, apparently for circulation.

Lead half-dollar (ANS 1934. 2010.22.11)

Official coinages. When other forms of metal currency—especially copper/bronze—were in short supply, governments sometimes produced official fiduciary coinages in lead as a means of preventing the collapse of quotidian transactions. Thus, in southern China of the Ten Kingdoms Period (AD 907-979) lead coins were cast both officially and in private with value ratings against copper cash coins. Lead sporadically occurs as a coinage metal in India of the Classical Period (first-third centuries AD), especially in central India, but also later under the occupation of the English East India Company in the eighteenth century. The Company’s lead pice not only filled a need for low-value coinage, but also returned a hefty profit since the face value of the coin was much greater than the cost of the lead from which it was made.

Lead pice, Mumbai, 1741 (ANS 1988.21.63)

These coin-like objects are distinguished from emergency coinages in that they were produced officially or privately usually to be exchanged for goods or services rather than to circulate as money, although in times when other low value coin was scarce they were pressed into service as emergency money. In Roman times, tokens, known as tesserae, were used by emperors and lesser officials in Rome and the provinces to distribute the grain dole and other bonuses to the populace. The also seem to have been used by private businesses. The ANS collection is notable for a group of tesserae from the Roman client-kingdom of Nabataea, which may have been distributed in the context of a religious celebration or were used as tokens to purchase votive gifts in a temple. English shopkeepers in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries also often produced their own tokens in part because there was rarely enough copper halfpence in circulation for daily transactions. Lead tokens made business more manageable and some of the more trusted issues even gained the status of local currencies. Lead tokens were still used by small businesses in North America and elsewhere in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Lead tessera (ANS 1967.160.11)

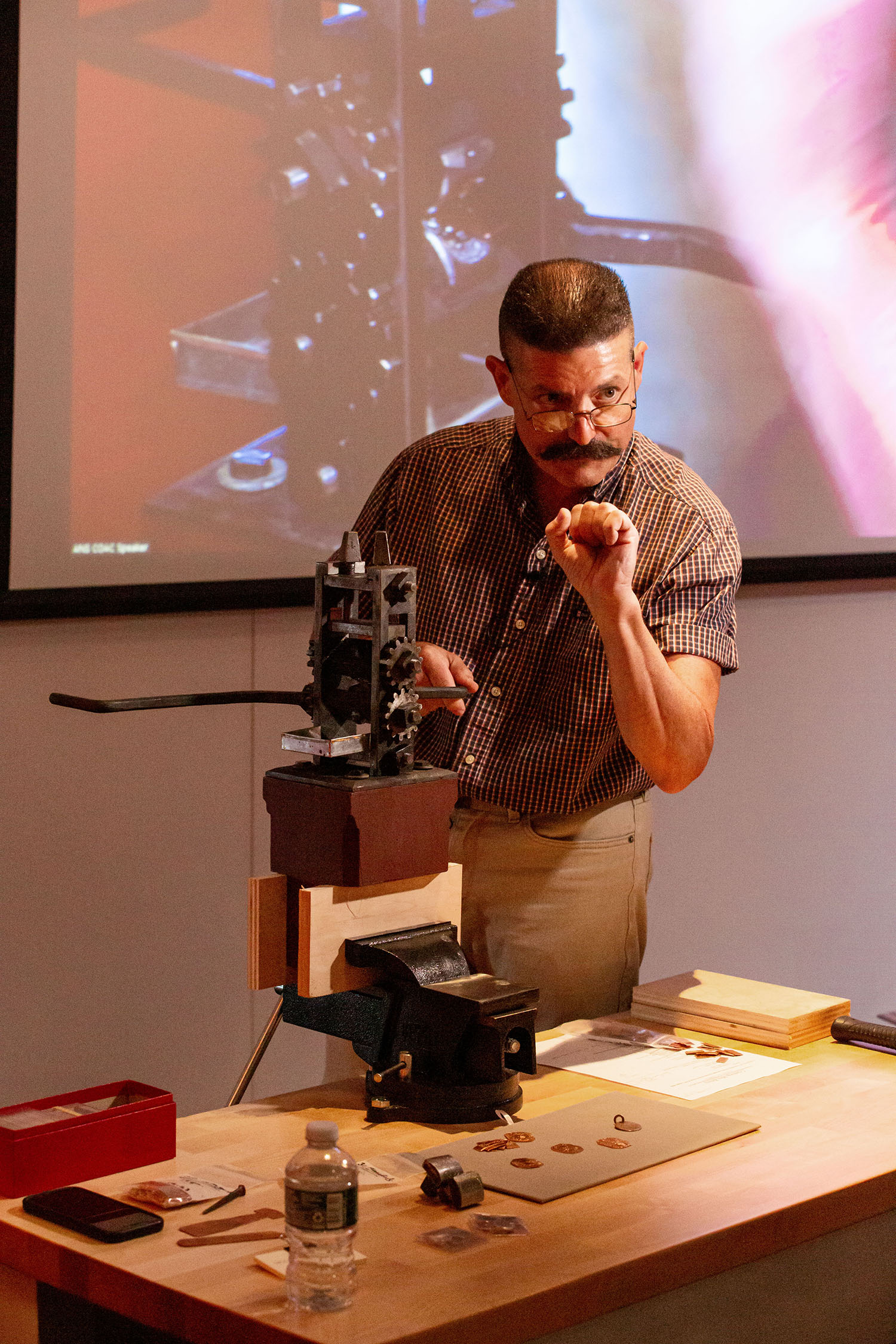

Test strikes and patterns. As a soft metal, lead was often used for trial strikes at many mints in different periods in order to test the quality of dies and their engraving or as patterns for coins and medals not yet struck. The ANS collection includes a variety of lead trial pieces and patterns for U.S. coins that were ultimately rejected by the Mint. It also holds numerous lead trial pieces for medals struck or planned by the American Numismatic Society during its long history as a medal-producing institution. Indeed, even as late as the 1990s lead blanks were used to demonstrate hammer-striking when the Society used to have its open house at the old Audubon Terrace location. Some readers may still have one of these ANS “test strikes” carried off as a memento. As one of the demonstrators back then, I still have mine. Out of a concern for safety, all demonstration strikes made at the ANS now use plasticene rather than lead.

Lead half-dollar, Philadelphia, 1859 (ANS 1956.122.3)

It is easy to love gold and silver, but this brief survey of the Society’s holdings of lead should shown that their humble cousin, lead, is of comparable interest from the historical and numismatic technical perspective. Just because they are often small, have less than stunning patinas, and could cause physical harm if you do not wash your hands after handling them, there is no reason why they should not sometimes share the spotlight with their shinier and more attractive relatives. After all, in some cases there might not have been the finished gold or silver coin in the trays if there had not already been a lead piece first.