“The Right of Trial by Jury Shall be Preserved” . . . Thanks to Numismatics

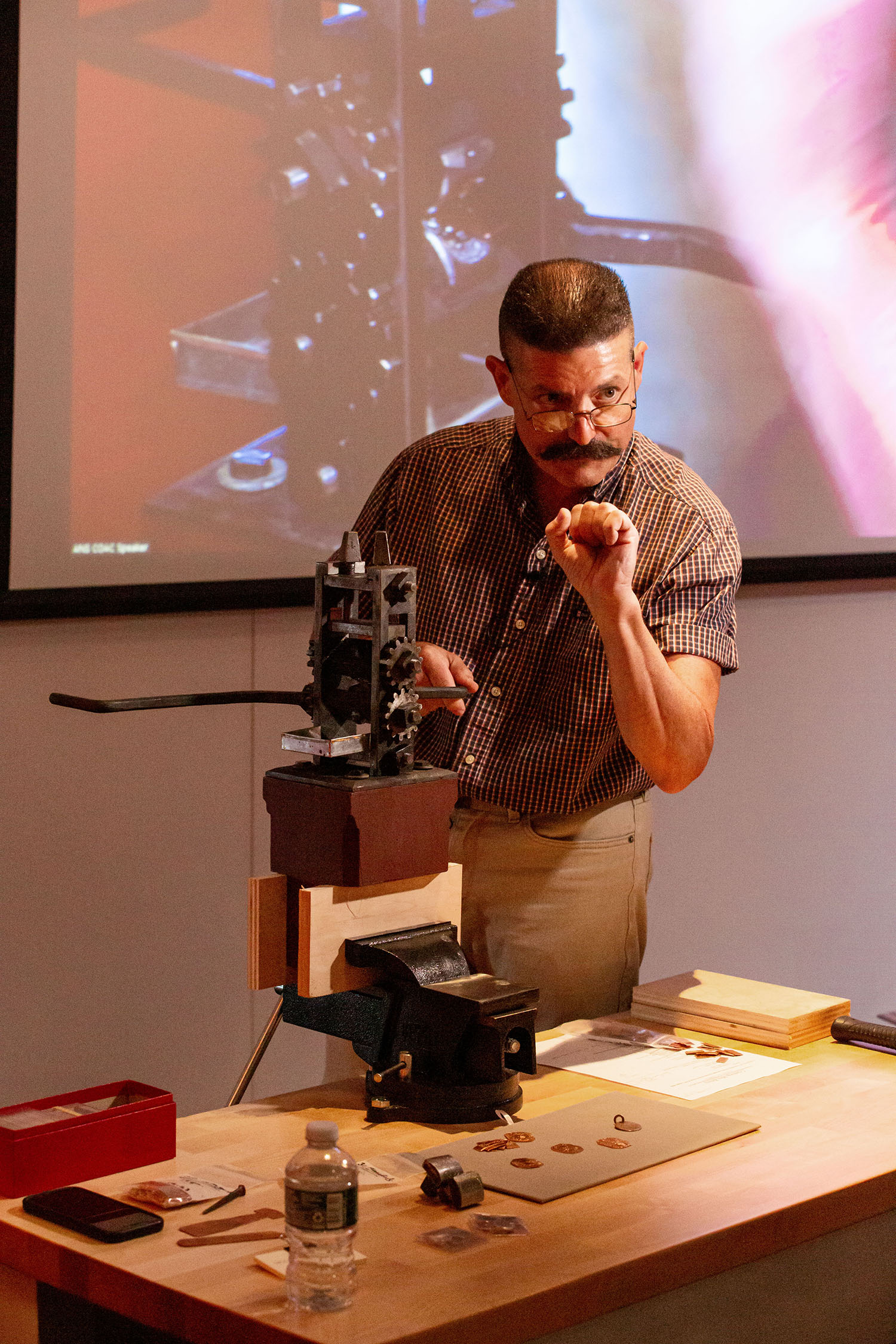

While few people truly hope to find themselves before a court of law, most should be happy that a jury is present when on trial (fig. 1). In the midst of such tense scenarios, few individuals stop to think (let alone care) about the historical processes that led to that development. However, even fewer recognize that a specific numismatic incident helped secure this right to American citizens.

In May of 1786, the General Assembly of Rhode Island authorized the printing of £100,000 in legal tender bills of credit (fig. 2). On its own, this was no strange occurrence. By this time, all the other newly-formed states of the Union had also issued paper currency, which was their legal right under the Articles of Confederation. Not unlike the paper currency of several other states, these notes were made a legal tender that “shall be received in all Payments” in the state. However, in August, the General Assembly further amended the legal tender status of the bills to be enforced by courts summarily without a jury trial or appeal.

By this time, 170,000 notes in 12 different denominations were released into circulation (6d, 9d, 1s, 2s6d, 3s, 5s, 6s, 10s, 20s, 30s, 40s, and 3 pounds). Unlike present-day money, colonial and pre-federal currency was issued in payment for specific objectives, such as the compensation of troops for a particular war or the construction of a specific building or utility. The May 1786 Rhode Island notes were issued to amortize a group of 4% 7-year loans on realty and known as the Tenth Bank.

Quickly, the legal tender status of the notes and, particularly, the juryless trial that ensued if a note was refused became a hot topic in the state. By September of that year, the case of Trevett v. Weeden had worked its way up the Rhode Island Supreme Court and heard by Justice David Howell. Everyone saw the inconsistency in the law, especially since the Constitution of Rhode Island had already guaranteed a trial by jury. The senior counsel for the defense, General James M. Varnum (fig. 3), successfully made the case that the colonial constitution of Rhode Island, despite being nullified by the American Revolution and held no legal footing, “continued in vigor as a part of the unwritten constitution of the new State.” The Court agreed and, in turn, gave them the power to decide on the constitutionality of any piece of legislation presented to them. On September 26, the May 1786 Currency Act has the distinction of being the first law in the United States to be declared unconstitutional and voided.

By December of 1786, the illegal features of the original act were amended, though the notes still remained a tender. In September 1789, their legal tender status was officially repealed, as the bills had depreciated down to only 10% of their stated values. Between 1793 and 1803, more than 96% of the original notes were burned by the State. Today, the legal right of trial by jury is protected by the Seventh Amendment to the Constitution, which was adopted as one of the Bills of Rights on March 1, 1792. For this, we have the Rhode Island currency of May 1786 to thank.