During the past century, a great deal of scholarly attention has been directed to elucidating the coinage, and through it the internal history, of Lycia before the arrival of Alexander. 1 This was inevitable. Preeminent in Homer among the peoples of Asia, the Lycians seem always to have possessed a strong sense of national unity, which kept them free of outside colonization and relatively free from foreign domination throughout the archaic and classical periods. Even under the Persian Empire, whose strength they could not resist, the Lycians retained some degree of autonomy, for local dynasts coined in their own names throughout the fifth and much of the fourth centuries. During this time, although inevitably influenced by the Greek and Achaemenid worlds, a vigorous and original culture flourished in Lycia, whose architecture, sculpture, and coins all evoke admiration today.

For over a century and a half after the fall of the last dynast, ca. 362 b.c., the Lycians seem to have struck virtually no coins. 2 But in the early second century b.c. our sources speak of a formal Lycian League of cities which were now thoroughly Hellenized, and which struck a large and uniform federal coinage in silver and in bronze. Most of this coinage has been loosely dated over the entire two-century span from 167 b.c., when Lycia was freed from Rhodian dominion, to a.d. 43, when she finally lost her autonomy and was absorbed into the Roman Empire. Although the League coins are frequently cited as evidence for the membership of this or that city in the League, they have received remarkably little direct study.

Indeed, the League itself has been little studied, presumably because the Lycians were not racially Greek, and their government was not considered part of the stream of Greek political development. 3 Yet the area was almost completely Hellenized by the time the League sprang up, and its institutions so far as we understand them seem thoroughly Greek. In this politically sophisticated federation, at the end of the second century b.c. the largest cities controlled three votes each in the assembly, while other cities, according to size, controlled two or one. 4 But an examination of the League's institutions is not, and cannot be, the subject of this study. The coinage can, however, tell us something of the League's changing membership at different periods, and at times illuminate Lycia's relationships with her neighbors—and among these neighbors must of course be classed Rome.

As has been stated, scant attention has been paid to the Lycian League's coinage. Several scholars early in this century examined certain series struck under Augustus and Claudius, 5 but the last work to survey even briefly the League coinage as a whole appeared over half a century ago. 6 Except for the BMC and Historia Numorum, which are inevitably incomplete and occasionally inaccurate as well as extremely imprecise about chronology and even the denominations in use, no useful treatment of the Lycian League's coinage exists.

The southern coast of Asia Minor consists chiefly of two large mountainous bulges. The eastern is Cilicia Tracheia, separated by the Pamphylian Gulf from the western, which is Lycia. Northeast of Lycia lies Pamphylia, the border, ill-defined, shifting several times during antiquity; to the north are Pisidia and Phrygia; to the west, again across a shifting border, Caria; and to the southwest, some fifty miles away, the powerful island of Rhodes.

Lycia extends approximately 80 miles east to west, and 40 north to south, with an area of about 3400 square miles. A mountainous land, its two highest peaks are just under and just over 10,000 feet—and this within 10 or 20 miles of the sea. There are few plains: one in the north central region, which played little part in Lycian affairs either in classical times or in the period of the League; one around Telmessus in the west; one along both sides of the Xanthus River, the heartland of Lycia; and one east of Limyra, on the southern coast.

Although Lycia enjoyed a network of roads under the Roman Empire, travel in earlier times was extremely difficult: Alexander avoided the mountainous southern coast by marching across the level country in the north. And even in modern times, only very recently has a road system been built, notably along the coast. Internal communications in antiquity were thus chiefly by sea or by the rivers which flow to the southern coast. Of these the most important, west to east, were the Xanthus, the Myrus, the Arycandus, and the Limyrus.

All of the known minting cities of the Lycian League lie within easy reach of the coast or of one of these rivers. Telmessus, a major city, is on the northern part of the western coast. Patara, Lycia's chief port, lies on the western portion of the southern coast, near the mouth of the Xanthus River. A few miles up that river is Xanthus, Lycia's largest city. And within easy reach of the river's tributaries to the north lie Sidyma, Pinara, Tlos, and Cadyanda. Within an area no more than 10 by 20 miles in the center of the southern coast are Candyba, Phellus, Antiphellus, Aperlae, Cyaneae, Trebendae, and Myra. Slightly to the east lie Limyra, Rhodiapolis, and Gagae, around a small coastal plain; up the Arycandus River, which flows through this plain, is Arycanda. And on the eastern coast, cut off by the high Solyma Mountains from the rest of Lycia, are Olympus and Phaselis.

Broughton has estimated Lycia's population in ancient times as 200,000; 7 Moretti considers this high. 8 Two hundred thousand would indeed be considerably greater than the current population, but this is quite possible, as Broughton notes that in many instances Asian areas and cities are known to have had ancient populations greater than their modern ones. Lycia's population, however, whatever its absolute size, was dispersed in many small communities. Pliny states that while Lycia formerly had 70 cities, in his time it contained but 36. 9 Strabo, speaking of ca. 100 b.c., says that 23 cities shared the vote in the federal assembly. 10 But numerous sympolities are known from inscriptions, and these doubtless each controlled one vote. And what, in any case, is the definition of a city as opposed to a deme or village? It is clear that speculation on the absolute number of "cities" is idle. We can be sure only that the Lycian population was scattered in many small communities over its mountainous land.

Sea trade and agriculture seem to have been the Lycians' chief sources of livelihood. Timber was a highly important product, but ancient writers mention also wine, fruits, fish, sponges, cattle, and goats—but no mines, and nothing exceptional that would explain the rather surprising amount of coin struck in classical times, or in the period of the Lycian League, as one of the results of this study has been that the surviving League silver is a very small sample indeed of the original output.

Early nineteenth-century explorers in Lycia included the Englishmen Capt. Francis Beaufort, Sir William Leake, Sir Charles Fellows, Sir Charles Cockerell, and others. Later in the century three Austrian teams visited the area and also wrote valuable accounts of the topography and copied many inscriptions: O. Benndorf and G. Niemann, E. Peterson and F. von Luschan, and R. Heberdey and E. Kalinka. 11 But Lycia has remained little known. Archaeological excavations started only after the Second World War, 12 and the area remains one of the least visited and least known in Asia Minor. Especially now that roads have been built, much of archaeological and numismatic interest will certainly appear in coming years.

| 6 |

A. W. Hands, Common Greek Coins (London, 1907), pp. 151–68, preceded

only by Warren, pp. 35–44, and W. Köner, "Beiträge zur Münzkunde Lyciens," pp. 93–122, in

M. Pinder and J. Friedlaender, Beiträge zur älteren Münzkunde

(Berlin, 1851).

|

| 7 |

Broughton, pp. 815–16.

|

| 8 |

Moretti, p. 172.

|

| 9 |

NH 5.101.

|

| 10 |

14.665.

|

Although neighboring lands were settled by Greeks in heroic and archaic times, Lycia managed to remain free of Greek colonization. 13 That several Lycian cities have Greek names does not contradict this statement, for in most cases it is known that these were not the cities' original names: Xanthus, for example, was called Arna in the Lycian language. Even the national name of the Lycians was adopted only during the Hellenization following Alexander's conquest, as in their own language the Lycians were the Termilai. Phaselis on the eastern coast was indeed a Rhodian foundation, but in early times this coast, separated from Lycia proper by the Solyma Mountains, was not Lycian but Pam-phylian.

The Lycian culture of classical times flourished in the Xanthus Valley and along the southern coast. Its limits, as shown by the characteristic and picturesque rock-cut and tower tombs and by inscriptions in the Lycian language and script, were the western coast of the Gulf of Tel-messus to the west, Bubon to the north, and Rhodiapolis to the east, with no such remains north or northeast of Arycanda and Rhodiapolis, and none on the eastern coast. Local dynasts, whom the coins show to have controlled shifting groups of cities, governed Lycia at this time. Some of these dynasts emerged at certain times as leaders of the whole people, the most outstanding being Pericles, who in the first half of the fourth century commanded all Lycia except the east coast. But the cities clearly retained some degree of autonomy, since in the fourth century coins were struck also in the names of several of the larger cities.

Lycia alone in western Asia Minor stayed free of Croesus's dominion in the sixth century. After the desperate but unsuccessful resistance of the Xanthians to Harpagus, 14 Lycia passed into the Persian Empire, but presumably on favorable terms, for the Lycian princes coined in their own names, and Lycia did not join her western neighbors in the Ionian Revolt. Later in the fifth century she was at least briefly a member of the Delian League, for the tribute lists for 446 b.c. assess the Λύϰιοι ϰαὶ συν[τελεῖς] for ten talents.

The dynast. Pericles, mentioned above, joined in the Revolt of the Satraps. When this collapsed in 362 b.c., Lycia was placed under the control of Mausolus of Caria, whose house continued to control Lycia until Alexander's arrival. The dynasts would seem to have disappeared under Carian rule, for it was the cities with which Alexander dealt, and which submitted individually to him.

After Alexander's death, Lycia fell to Antigonus. The Ptolemies, however, also coveted it; and, after various vicissitudes, the area came completely under their control in the 270s and remained Egyptian territory until the end of the century. Papyri show that the Lycian cities did not pay tribute but a variety of specific taxes, and a well-known inscription from Telmessus gives a vivid picture of Ptolemaic exploitation. 15 This document of 240 b.c. records several acts of one Ptolemy son of Lysimachus (perhaps a nephew of Ptolemy III) upon receiving control of the city from the Egyptian king. Ptolemy son of Lysimachus found the city "suffering from the wars"—i.e. the Syrian Wars. He remitted the dues on certain crops and pasturage, and regulated more strictly the taxes due on a variety of grains, in order to curb the illegal exactions of the tax farmers. The Egyptians nonetheless thoroughly exploited Lycia economically; and the large number of Lycians known to have served in Ptolemaic armies also attests the impoverishment of the area during the period of Egyptian control.

This control weakened late in the century under the ineffective Ptolemies IV and V, and in 197 b.c. Antiochus III of Syria took possession of Lycia. It is known specifically that he took Limyra, Andriace (Myra's port), Patara, Xanthus, and probably Telmessus, but the sources read as though he gained control of the whole country. 16

It is to this period that a fragment of Agatharchides may belong, although there are difficulties: "the Arycandians, neighbors of the Limyreans, having become involved in debt because of their profligacy and extravagances, and because of idleness and fondness for pleasure being unable to repay their loans, turned their hopes to Mithradates, thinking that they would be rewarded by the abolition of their debts." 17 If the attribution to Agatharchides is correct, the fragment cannot refer to the invasion of Mithradates VI of Pontus, for Agatharchides wrote in the late second century b.c. But the reference to the cancellation of debts would fit nicely, for Mithradates did enact just such a policy. The fragment, however, does not sound like what we know otherwise of the Lycian response to Mithradates.

The usual view is that the fragment refers to the time of Antiochus III. When in 197 he sailed along the southern coast of Asia Minor, winning over the cities, he sent his army from Syria to Sardes under two generals. As one of these was named Mithradates, it is to him that the fragment may refer. The cancellation of debts in this case might well refer to Ptolemaic taxes (it would appear safe in any case to disregard the reference to profligacy and extravagance), although it is perhaps doubtful that the Egyptians at this late date were able to collect their revenues with much rigor. Nor is it likely that Antiochus's army passed very near to Arycanda. It is a pity we cannot be sure to which ruler, Antiochus III or Mithradates VI, this fragment refers, for it would be valuable to know how far either one of them penetrated into Lycia, and what the local response was.

There is no specific record of how easily Antiochus occupied Lycia. Livy says that in Cilicia only Coracesium resisted him and that the Rhodians helped "preserve the liberty of" several Carian cities. He then exasperatingly concludes with "it is hardly worth while to record in detail the events in this part of the world." 18 An inscription records Antiochus's dedication of Xanthus to Leto, Apollo, and Artemis. 19 This is usually taken as indicating that Xanthus was able to arrange some sort of compromise with the Syrian king, but it may have been a kind of face-saving measure, if not an indication that Lycia's relationship to Antiochus was closer to alliance than subjection.

One telling incident, however, seems to show that the Lycians were willing allies of Antiochus. When in 190 a mixed Roman and Rhodian naval force attempted to win over Patara with its important harbor, "the citizens, joining the troops of the king whom they had as a garrison," fought with the invaders, and, as the battle went on, "larger numbers were rushing out of the city, and … the whole population was pouring forth." 20 But finally they (and Livy says "the Lycians," not the Syrian garrison) were defeated and driven back into the city; the Romans, however, did not take the city but sailed off. A Lycian contingent of light-armed troops also served in Antiochus's army at Magnesia. 21

That this help was given willingly is also implied by the report that the Ilians, who interceded for Lycia at Apamea, did not plead duress, as surely would have been expected were such a plea possible. They merely begged forgiveness, for the sake of the kinship between Ilium and Lycia, for the Lycians' ἁμαϱτήμενα. 22 Polybius reports that the Ilians were successful to the extent that the only punishment Rome inflicted on Lycia was to grant her to Rhodes, who had taken the winning side in the late war. For her help, Rhodes was awarded Caria south of the Maeander and all of Lycia exceptTelmessus, which was given to Eumenes. 23

But Lycia bitterly resented this ruling, and Rhodes apparently had to subjugate the country forcibly. The Lycians revolted repeatedly, and the Rhodians later spoke of the "three wars" they had to wage there. A Lycian embassy to Rome in 177 procured an attempted compromise: Rome stated, no doubt falsely, that she had never intended the Lycians to be subjects of the Rhodians, but allies. This pleased neither side. At last the Rhodians made the mistake of attempting to mediate in the Roman-Macedonian conflict and the ensuing negotiations, and in 167 b.c. Rome, angered, stripped Rhodes of her mainland territories and declared the Lycians free. 24

From 167 until a.d. 43, when Claudius formally incorporated them into the Roman Empire, the Lycians retained their freedom, which, however, became increasingly nominal as time went on. To this period of slightly over two centuries the coinage of the Lycian League has traditionally been ascribed. The lower limit must still hold, but the upper limit should be raised somewhat, as will be seen.

| 11 |

O. Benndorf and G. Niemann, Reisen im südwestlichen Kleinasien 1: Reisen in Lykien und Karien (Vienna, 1884); E. Peterson and F.

von Luschan, Reisen im südwestlichen Kleinasien 2: Reisen in Lykien,

Milyas, und Kibyratis

(Vienna, 1889); R. Heberdey and E. Kalinka, Bericht über zwei Reisen im südwestlichen Kleinasien, Denkschrift der Akademie Wien 45 (Vienna, 1896). For

these and other travelers' accounts, see the bibliographies in the works cited in n. 3. Recent works dealing with the area

are TSS, which treats only Lycia's eastern coast; and Bean's posthumous

book, Lycian Turkey (London and New York, 1978), a splendid survey

which appeared only after the completion of the present study.

|

| 12 | |

| 13 |

This synopsis of Lycian history down to the arrival of Antiochus III contains

nothing, I believe, that is not generally accepted. Fuller treatment and specific references to the ancient sources can be

found in

Treuber, Magie, and Jones.

|

| 14 |

Herodotus 1.176.

|

| 15 |

TAM 1 = OGIS 55.

|

| 16 |

Livy 33.19–20 mentions no individual cities, but Antiochus's possession of Patara is repeatedly cited in 37.16 and elsewhere. Specific cities are given in

Jerome, Comm. in Daniel

11.15 (Porphyrius frag. 46 in F. Jacoby, Die Fragmente der griechischen Historiker, 2

Teil, B [Berlin, 1929], p. 1224); this and Jerome on Daniel 11.17–19

(Jacoby frag. 47), as well as Livy, imply that Antiochus won control over all

Lycia.

|

| 17 |

Athenaeus 12.527F. See also Kalinka in TAM, pp. 288–89, and Magie, pp. 1384–85, n. 41.

|

| 18 |

33.20.

|

| 19 |

TAM 266 = OGIS 746.

|

| 20 |

Livy 37.16.

|

| 21 |

Livy 37.40; Appian, Syr. 32.

|

A strong sense of national consciousness and unity is evident throughout Lycian history and a league of some sort is often assumed in classical times, chiefly because of the Λύϰιοι ϰαὶ συν[τελεῖς] entry in the Athenian tribute lists and because of the common reverse type, the triskeles, of so many of the dynasts' coins. 25 Mutual cooperation among the Lycians is clear, but to what extent this was voluntary rather than formalized and obligatory is not known. In any case, any early League would have been one of princes, not of cities; and it would have come to an end in the fourth century when the country was made subject to Mausolus.

The start of the League has often, especially in numismatic circles, been taken as 167 b.c. This date was based not only on the obvious fact that in 167 Lycia became free, but also on the BMC's dating of the League coinage. Hill in the BMC dated the League's silver coins to after 167 not only because of political considerations, but also because the earliest League silver so clearly imitated the Rhodian plinthophoric drachms and, at the time the BMC was written, the Rhodian plinthophoroi were themselves dated to after 167. 26 But Hill also, unfortunately, flatly stated that the Lycian League commenced only upon the withdrawal of the Rhodians; 27 and Head in Historia Numorum has followed the BMC in calling 167 the start both of the coinage and of the League itself. 28

But the start of the Lycian League has long been suspected by its historians to have occurred earlier, quite possibly in the late third century. Proof both of this and of an earlier date for the Rhodian plinthophoroi has slowly been accumulating. The Rhodian coins will be discussed below, but a summary of the evidence for a late third-century start for the League follows.

Both Treuber and Fougères had suggested that the League's origin was to be put in the third century, probably in its closing years when Ptolemaic control was weakening, 29 but J. A. O. Larsen first presented hard evidence for the League's existence before 167 b.c. He noted in 1945 that OGIS 99, which must be dated between 188 and 181, is a decree of τὸ ϰοινὸν τῶν Λυϰίων; and that in the 180s b.c. there were recorded at Athens and at Cos athletic victors identified by a form of ethnic characteristic of federal states: Λύϰιος ἀπὸ Γάγων Λύϰιος ἀπὸ ᾽Αντιφέλλου, Λύϰιος ἀπὸ Πατάϱων. Larsen also believed that the numismatists' dating of League coins to after 167 was arbitrary. 30

Dramatic evidence for an even earlier League, organized and effective, appeared shortly thereafter. In 1948 G. E. Bean published a long inscription from Araxa at the northern end of the Xanthus River. 31 The monument is a eulogy of one Orthagoras of Araxa, who had a long and varied career in public service. Moagetes, tyrant of Bubon, just north of Araxa, had been raiding Araxa's territory. Orthagoras first commanded his city's troops in fighting off the Bubonians, and went as Araxa's ambassador to the larger city of Cibyra, to which Bubon was evidently subject in some way. He also, which is what interests us here, went to the Lycian federal government in order to seek its aid. In this he was unsuccessful, the League apparently regarding the dispute as a mere border skirmish; but the League did appoint Orthagoras as its own ambassador to Moagetes, with whom some settlement was eventually reached.

Subsequently two would-be tyrants seized Xanthus, killed many of the citizens, and set themselves up as despots. This time, its major city threatened, the League intervened militarily, with Orthagoras commanding Araxa's contingent, and the tyrants were, after some difficulties, overthrown. Orthagoras next was involved in a war, whose outcome is unknown, between the League and Termessus, most probably Termessus Major in Pisidia.

He then successfully represented Araxa in a territorial dispute with an unnamed neighbor: the arguments were made to the federal government, presumably to a court of some sort, and were settled peaceably by that body. Orthagoras also arranged admission to the League of a small town near Araxa. Finally, he served as envoy to the first two of the pentaeteric festivals organized by the Lycians in honor of 'Ρώμη θεὰ ἐπιφανής.

There is no clear-cut evidence of the date of this highly interesting inscription, but various indications point to ca. 180 b.c., which now seems generally accepted. 32 One reason for the dating is the use of praenomina alone to refer to two Roman legates: this usage, characteristic of the early second century, is not found later. Another reason is the establishment of the cult of 'Ρώμη θεὰ ἐπιφανής. The epithet is most easily understood in relation to Rome's defeat of Antiochus, and thus the two festivals Orthagoras attended in his official capacity late in his career would have been in 189 and 185 b.c. 33 His active life, and that of the League, thus seem to antedate the 180s by some decades.

While this inscription provides little detail about the internal organization of the League, it does present us with a clear picture of an active and effective confederation in the earliest decades of the second century, and probably at the very end of the third century as well, for Orthagoras's career must have extended over some considerable time. The League sent ambassadors; waged wars; settled disputes, presumably in a court; and evidently had a fixed seat of government to which appeals could be sent, with an executive committee there of some sort which could make decisions between regular sessions of the assembly.

A final bit of information enables us to set the League's formation at least as early as 206/5 b.c. An illuminating study of the forms of ethnics used by individual Lycians, which extends the work on this subject by Larsen mentioned above, forms part of Moretti's lucid work on the Greek leagues. He finds three types of ethnics. The simple Λύϰιος, used chiefly by mercenaries, is found from the mid-fourth to the mid-third century. The federal ethnic, Λύϰιος ἀπὸ, e.g. Πατάϱων, is found first at the very end of the third century (see below), while most examples date from the early or middle second century. The simple municipal ethnic, e.g. Παταϱεύς, first appears in the first half of the second century, and later prevails over the federal ethnic by the time the predominant Roman influence in the affairs of the east had made membership in the League increasingly meaningless. Moretti observes that it is not without significance that the last known example of the federal ethnic belongs to the Sullan era. The importance of these ethnics for the start of the League, however, is that the earliest example of the federal ethnic found by Moretti is in a decree of Miletus, dated to spring 206-spring 205: the decree grants citizenship to a number of foreigners, among them one [Σϰ]ύμνος Πολέμωνος Λύϰιος ἀπὸ Ξάνθου. 34

It is accordingly to the decades preceding 167 b.c. that the following bronze issues have been assigned. They surely antedate the League's silver, with its profile heads, whatever the exact date of the silver's introduction, and are also presumably earlier than the Rhodian plinthophoroi which the League silver imitated. As will be seen below, the Rhodian coins are now known to have commenced some years before 167 b.c., but that date will be used here as a convenient and historically significant terminus ante quem for the Lycian League's bronzes of Period I.

| 22 |

Polybius 22.5.

|

| 23 |

Polybius 21.24 and 45; Livy 37.56 and 38.39.

|

| 24 |

Polybius 24.15, 25.4–5, 30.5, and 30.31; Livy 41.6, 41.25, 42.14, and 44.15. Livy again maddeningly says (41.25) that "it

is not worth

relating" the Lycians' struggles with the Rhodians.

|

| 25 |

See Mørkholm-Zahle, pp. 112–13.

|

| 26 |

BMCCaria and BMCLycia use 168, or at times 166, instead of 167, but 167 b.c. would appear to be the correct date. That the Lycian silver coins imitated the Rhodian plinthophoric drachms is stated not

in

BMCLycia but in BMCCaria, p. cvi; the Rhodian plinthophoroi's start is there dated to ca.

167 (pp. cix and 252). Perhaps because this is not mentioned specifically in BMCLycia, Larsen seems unaware of this

reason for Hill's dating of the Lycian drachms, regarding the accepted terminus post quem of 167 b.c. as purely

arbitrary ("Representation and Democracy in Hellenistic Federalism," ClassPhil 1945, pp. 72f.).

|

| 27 |

BMCLycia, p. xxii.

|

| 28 |

HN

2, p. 693 (168 b.c. instead of 167 b.c., but see above, n. 26).

|

| 29 |

Treuber, p. 149; Fougères, pp. 15f.

|

| 30 |

ClassPhil 1945, p. 72 f. See above, n. 26.

|

| 31 | |

| 32 |

Bean (above, n. 31) was uncertain about the date, but other scholars have agreed on ca. 180 b.c.:

J. and L. Robert, "Bulletin Épigraphique," REG 1950, pp. 185–97, no.

183; L. Moretti, "Una nuova iscrizione di Araxa," Riv.Fil.Cl. 78 (1950), pp. 326–50; Larsen, "The Araxa Inscription and the Lycian

Confederacy," ClassPhil 1956, pp. 151–69; Jones, pp. 100–101.

|

| 33 |

It may be objected that the Lycians would not have instituted, and then continued to celebrate, a cult of the goddess Roma

just as their

country was given by Rome to Rhodes.

But immediately after Apamea the Lycians had received a false report: the Ilians, who had interceded for them, reported to

the Lycians that

they had successfully secured their freedom; only later did the bitter truth become evident (Polybius 22.5). The

Roberts (see above, n. 32) accept this interim as the time of the establishment of the cult; and, as they say, once

the Lycians had publicly announced festivals in honor of the world's leading power and their only hope of eventual relief

from Rhodian

occupation, what else could they possibly do but continue those festivals?

|

| 34 |

Moretti, pp. 188–90; the Miletus decree is Milet III, Das Delphinion

(Berlin, 1915), p. 205, no. 46 (as cited in Moretti, p. 215, n. 36). Perhaps because of the

high interest of the Orthagoras inscription, this clear evidence of Moretti's for the League's existence in the third

century has been ignored by Jones and Larsen in their subsequent works. That the Ptolemies were

still in control in 206–205 b.c. is shown by TAM 263, the latest evidence for Egyptian

rule in Lycia: the inscription records the dedication of a temple at Xanthus on behalf of Ptolemy V, who acceded late in 205 (or perhaps

204).

|

| 1 |

Most recently, O. Mørkholm has been analyzing with considerable success the coinage of Lycian dynasts of classical times.

See Mørkholm and Mørkholm-Zahle, and also N. Olçay and O.

Mørkholm, "The Coin Hoard from Podalia," NC 1971, pp. 1–29, and O.

Mørkholm and J. Zahle, "The Coinages of the Lycian Dynasts Kheriga, Kherêi and Erbbina," Acta Archaeologica 47 (1976), pp. 47-90.

|

| 2 |

Any minting during this period was minimal. Dr. Mørkholm tells me he suspects that some of the cities' coinages

contemporary with the dynasts' may have continued for a while after the dynasts' overthrow; A. D. H. Bivar has suggested

that certain small bronzes with Aramaic inscriptions were struck in Lycia under Persian rule

in the later fourth century ("A 'Satrap' of Cyrus the Younger," NC 1961, pp. 124–27); and some of the autonomous bronze

of League cities may possibly antedate the League coinage (e.g. BMC

Patara 11–12).

|

| 3 |

The earliest works to deal with the Lycian League and its history are Treuber and Fougères; the former is concerned chiefly

with Lycian

history, with which it deals exhaustively, and the latter concentrates on the League and its institutions. E. A. Freeman

also discussed the League briefly in his History of Federal Government in Greece and Italy

, 2nd ed. (London and New York, 1893). Renewed attention has been paid to the League in the

last two decades by Moretti, by J. A. O. Larsen, GFS and a number of

articles, and by S. Jameson in a revised article on Lycia in RE Suppl. 13. H. von Aulock,

Gordian

, gives a convenient summary of Lycian geography and history, and a valuable compilation of sources (ancient and modern literary,

inscriptions, coins) for each of the twenty cities which struck under Gordian. And of course

Lycia and the League are also discussed in Magie and in

Jones.

|

| 4 |

Strabo 14.665.

|

| 5 |

This study deals with the post-Alexander Lycian League and its coinage in silver and bronze, ca. 200 b.c.–a.d. 43. Approximately 1,825 League coins have been located and are catalogued. Coins are considered League strikings if their markings include either 1) ΛΥΚΙΩΝ, or ΛΥ, the federal ethnic, or 2) ΚΡ or ΜΑ, the abbreviations of the League's two great subdivisions in the late first century, Cragus and Masicytus; or both types of inscription. Pseudo-League strikings of Olympus and Phaselis, with ΟΛΥΜΠΗ or ΦΑΣΗΛΙ replacing ΛΥΚΙΩΝ, are also included in the catalogue. Nineteen or twenty Lycian cities struck League coinage, and a few also struck autonomous issues during the second and first centuries b.c. These autonomous issues are not treated here.

Throughout the study, the term "mint" is used in the sense of the issuing authority, not necessarily the location at which a coin was actually struck.

For lack of a better term, "Period" has been used to denote the five major divisions of the League's coinage, alternately bronze and silver. There is, however, some considerable chronological overlap between Periods II and III, III and IV, and IV and V.

The cataloguing varies somewhat between the bronze and silver issues. Periods II and IV, the silver coinages, have series denoted by Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3). Here and in the silver issues of Appendix 3, obverse dies are numbered; reverse dies are indicated by lower case Roman letters (a, b, c); and brackets to the right indicate reverse die identities. Asterisks indicate coins illustrated.

Periods I, III, and V, the bronze coinages, have series denoted by upper-case Roman letters (A, B, C). There and in the bronze issues of Appendix 3, dies are not numbered, and Greek minuscules (α, β, γ) indicate merely the coins selected for illustration.

Relative die axes are not given because virtually all are ↑↑, with the few variations either ↑↗ or ↑↖; the only exceptions to this rule are issues of very small coins such as issue 4, in which a significant number of axes are random.

In the following catalogue of Period I, dies are not numbered. The three coins of issue 1 are from three pairs of dies, and the dies of issues 3 and 4 cannot be identified with certainty. Relative die axes of the few coins known of issues 1–3 are, like those of all Lycian League issues, ↑↑ with the few variations either ↑↗ or ↑↖. In issue H, however, composed of very small coins, in which a significant number of axes are random.

Coins illustrated are indicated by Greek minuscules (α, β, γ) merely for the purpose of identifying the coins on the plates and to facilitate reference to them in the text. Neither these letters nor the sequence of coins catalogued indicate particular dies, and only a representative selection of obverse dies is illustrated.

Quadruple Units:

Obv. Laureate bearded head of Bellerophon, facing.

Rev. ΛΥΚΙΩΝ Chimera r.; in exergue,  (preserved only on 1α).

(preserved only on 1α).

Double Unit:

Obv. Head of Apollo facing; to l., bow and quiver.

Rev. ΛΥΚΙΩΝ Apollo Patroös standing facing, holding branch (probably, although it is not preserved) in outstretched r. hand, and bow in lowered l. hand.

Units:

Obv. Laureate head of Apollo facing; to r., cithara.

Rev. ΛΥΚΙΩΝ Head of Artemis facing; to l., bow and quiver.

Quadruple Units: 3 coins, 3 obv. dies, av. wt. 3.53

Double Unit: 1 coin, wt. 2.15

Units: 3 coins, av. wt. 1.15

1. Quadruple Units.

α. Private coll. 4.12; β. Paris 2.86 = "Rhodes," p. 31, fig. 4 = BMC pl. 44, 14 = E. Babelon, "Récentes acquisitions du Cabinet des Médailles," RN 1893, p. 336, 22; Oxford 3.62, purchased at Kestep in the Xanthus Valley = "Coins Lycia," pp. 37 and 41–42, 34.

2. Double Unit.

α. Oxford 2.15, purchased at Kestep = "Coins Lycia," pp. 37 and 42, 35.

3. Units.

α. London 1.03 = BMC p. 38, 4; β. Paris 1.41 = Waddington 3007; Berlin 1.00.

Units:

Obv. Radiate bust of Apollo facing; to r., cithara (present on many and perhaps all specimens).

Rev. ΛΥΚΙΩΝ Bow and quiver.

Units: 15 coins, av. wt. 1.07

4. Units.

α. New York 0.98; β. Paris 1.26 = Waddington 3009; γ. Oxford 0.86; Berlin 1.32, purchased at Pinara, 1.04; Copenhagen 1.23 = SNG 39, 0.95 = SNG 40; London 1.69 = BMC p. 38, 1; New York 1.26, 1.07, 0.86; Paris 1.00 = Waddington 3008, 0.61; Vienna 1.11, 0.79.

Issues 1–4 differ from all other League issues in bearing only the simple inscription ΛΥΚΙΩΝ, without further city or district identification. (The exergue monogram of issue 1 cannot, perhaps fortunately, be equated with any known mint—but its position and the fact that it is a monogram rather than simple initials would indicate a reference to an individual rather than to a mint, whatever that individual's relationship to the coinage.) Issues 1–4 are also alone among League issues in bearing facing heads, as did the dominant coinage of the area, the Rhodian, down to the 170s b.c. Sir Edward Robinson long ago in 1914 recognized that these four issues were associated and that they were among the earliest issues of the Lycian League. 35

Issues 3 and 4, which are the same size and weight (average weights 1.15 and 1.07, respectively), appear to be not contemporary but successive issues. Issue 4 appears to be the later, with its inanimate reverse type of bow and quiver both simpler in execution than the facing head of issue 3, and also related to the crossed bow and quiver of later small bronze issues. 36

The average weight of the three known specimens of issue 1 is 3.53; the single weight of issue 2 is 2.15. These agree tolerably well with a quadruple and a double, respectively, of the weight of the smallest denomination represented by issues 3 and 4; and issues 1 and 2 may then be considered multiples of one or another of these smaller issues. Issue 3 seems the more likely, as it, like 1 and 2, bears two animate types, and like them appears to show a simple head rather than a bust, and a radiate one at that, such as appears on issue 4. Accordingly, issues 1–3 have been placed in Series A of the Lycian League's first period of coinage, and issue 4 in the following Series B.

All of Period I's types show connections with the Xanthus Valley, the heartland of Lycia and presumably of the League, and this is appropriate for the League's first coinage, possibly minted in one or another of the major western cities of Xanthus and Patara. And, al- though the Xanthus Valley is probably the area of Lycia most travelled by antiquarians and scholars during the last two centuries and thus would be expected to provide more coin provenances than other areas, it is noteworthy that all three known provenances of Period I coins are in the west.

The types of issues 3 and 4 are those of certain small bronzes of Patara, 37 but whether these are earlier or later than the League coins is not clear.

Although the single coin of issue 2 is poorly preserved, its reverse representation of Apollo is precisely that found on Lycian coins throughout the League's history and even later: Apollo (sometimes radiate), stands left (facing or half-facing), clad in a long gown, holding a branch (sometimes filleted) in his extended right hand and a bow (and sometimes also an arrow) in his lowered left hand. This most probably is the figure portrayed on League bronzes of various cities in the mid-first century b.c.; 38 and is without a doubt that shown on the late first-century bronzes of the districts of Cragus and Masicytus, 39 on both the silver and bronze of Claudius from, probably, a.d. 43, 40 and on the Imperial bronzes of Gordian III from the mid-third century a.d. 41 The base lines on Claudius's and Gordian's coins show that a statue was portrayed, and the Apollo of Gordian's coins, sometimes shown in his temple, is unquestionably a cult image. But in any case the consistent iconography, unvarying over more than four centuries, demands a specific model. This can only be the renowned Apollo Patroös at Patara, for it is Patara's coins under Gordian which make extensive and virtually exclusive use of this figure. Apollo's cult and oracle at Patara were widely famed throughout antiquity, and it is strange that the Apollo on Gor- dian's coins has never, apparently, been identified as the actual Apollo of Patara. 42 So too must the earlier coins, under Claudius and under the free League, show the same cult image.

Inscriptions reveal that the Lycian League's records were kept at Patara, and Apollo's temple there has been suggested as the actual repository. The coins would seem to confirm this. The coins' Apollo is here called Apollo Patroös, the epithet under which he was known to the Patarans and to the League. Numerous inscriptions of the League refer to Apollo Patroös, whose priest was a League official, and whose cult with its oracle was celebrated at Patara. 43

Issue 1 shows a spirited rendition of the chimera, body tense, head facing. When Bellerophon, banished from Corinth, arrived at "Lycia and the stream of Xanthus," the first task assigned him by the "king of wide Lycia" was to slay this mythical creature, part lion, part goat, and part serpent, which breathed forth terrible fire. 44 In later times the chimera became localized and identified with a burning jet of natural gas escaping from a hillside above Olympus on the eastern coast; this weak flame can still be seen today. The identification of the monster with the natural phenomenon may have been made in the third century b.c., 45 but as several localities in Lycia alone were named Chimera, one suspects that gas may have escaped from the earth also in other places in this land so subject to earthquakes.

In any case, the coins show a mythical creature and not a gas flame, and it is with the city of Xanthus that the myth is connected. Strabo furthermore specifically states that the scene of the myth was the mountains of the western coast. 46

By the time the coins of Period I were struck, Lycia had become quite thoroughly Hellenized, and the chimera of the coins may well be understood as a deliberate reference to the Greek Bellerophon, grandfather of the Lycian Homeric heroes Glaucus and Sarpedon. Furthermore, the bearded head of issue 1's obverse may represent Bellerophon himself. Babelon suggested that the head was Helios, "type rhodien et carien." 47 But Helios is never, to my knowledge, shown bearded. Hill in the BMC did not describe the obverse; and Robinson called the head Heracles, believing that the Lycian obverse imitated certain coins of Selge which show a head of that deity. 48 But the style of the Lycian and Selgean coins is quite dissimilar, those of Selge showing the hair and beard in short, tightly curled, distinctly separate locks, while the Lycian heads' hair and beard are loosely waved and long and flowing. And Heracles, while he appears occasionally on Lycian coins of the classical period, has no particular connection with either Lycia or the chimera, while Bellerophon assuredly does.

Even though it was probably struck more than a century and a half before the first League coins, the coinage of the dynast Pericles was the last major coinage struck in Lycia before the League's. In these circumstances Pericles's coinage may have circulated for some considerable time, and might be considered to have furnished some of the models for the League coinage. The two League denominations represented by issue 2 and issues 3 and 4 (here termed double units and units, respectively) are the same sizes and approximate weights of the two small bronze denominations of Pericles, the chief if not the only Lycian bronze prior to the League's. 49 And Pericles's staters showing his facing laureate head, with long flowing hair and beard, 50 may possibly have served as the artistic prototype for the head of issue 1.

Whether or not issue 1 portrays Bellerophon, however, the choice of the chimera for the reverse must be significant. While the chimera is depicted in Lycian art from the late fifth century onward, there is but one instance of its use on Lycian classical coinage, although other monsters are frequently depicted. 51 Its appearance on issue 1 would seem to be intended to stress the Lycians' ties with Greece and with the Greek world, and if this is so, the most probable time for the commencement of Period I is the time of the Lycians' alliance with Antiochus and other Asiatic Greeks against Rome. It is worth noting that Telmessus, a major Lycian city which was not a formal member of the Lycian League until Augustan times, 52 also issued bronzes under Antiochus's dominion. These coins were the size of issue 1, with facing Helios head on obverse and Apollo seated on the omphalos on the reverse, as on Seleucid coins. 53

Period I must have ended before the Lycian adoption of the Rhodian plinthophoric format, with obverse head in profile and reverse type in incuse square. This is the format of most of the League coinage, especially the silver, and it is first seen on the silver drachms of the following Period II. A discussion of the date of this style's introduction, first at Rhodes and then in Lycia, will be found in the commentary on Period II.

| 35 |

"Coins Lycia," pp. 41–42.

|

| 36 |

See below, the units of Period III and the half units of Series A of Period V.

|

| 37 | |

| 38 |

E.g. Plate 1, A and B, bronze coins of Period III (63α and 71α).

|

| 39 |

E.g. Plate 1, C, a bronze coin of Series F of Period V (222δ). Series E also shows the same figure.

|

| 40 |

E.g. Plate 1, D, a drachm from Appendix 3's obverse die C2.4; and E, a bronze coin from Appendix 3 (C11α).

|

| 41 | |

| 42 |

On Apollo Patareus and Apollo Patroös, see RE II, col. 63 (Wernicke). G. F. Hill long ago equated

the Apollo of Claudius's coins

with the figures shown on the Masicytus bronzes and the Imperials of Gordian, but made no suggestion as to the prototype ("Miscellanea," NC

1903, p. 402). Even von Aulock in his recent

Gordian

did not attempt to identify the coins' Apollo.

|

| 43 | |

| 44 |

Iliad 6.172f.

|

| 45 |

RE III, col. 2281, s.v. Chimaira 2 (Ruge). Strabo

speaks of the locality called Chimera in the west (14.665). Pliny mentions one on the southern coast (NH 5.131) and one in the east (NH 5.100), and says that the latter is one of two nearby

places where fires burn.

|

| 46 |

14.665.

|

| 47 |

RN 1893, p. 336, 22.

|

| 48 |

"Coins Lycia," p. 42, n. 19: BMC Selge 35. This coin shows

Heracles's head to r.; 36–44, with facing heads, would seem closer parallels.

|

| 49 |

BMC, pp. 36–37, nos. 158–62 and 163–64. The sizes are those of the League issues 2, and 3–4. Pericles's weights

average 2.03 (14 specimens located) compared to issue 2's single weight of 2.15; and 1.18 (12 specimens located) compared

to issue 3's

1.15 (3 specimens) and issue 4's 1.07 (15 specimens). See Table 8. Other extremely minor bronze issues possibly struck in

Lycia before the League coinage are mentioned in n. 2.

|

| 50 |

SNGvAulock 4249–53.

|

| 51 |

Traité II.2, 219; see also Mørkholm-Zahle, p. 92.

|

| 52 |

See pp. 212–13.

|

| 53 |

BMC 1.

|

There are two drachm coinages which have in the past been erroneously attributed to Lycia. The first of these is a series of pseudo-Rhodian drachms, without ethnic, whose obverse shows a facing head of Helios with an eagle in front of one cheek, and whose reverse shows the usual Rhodian rose with a great many differing combinations of letters and monograms. 54 It was in the last century ascribed to various cities of Caria, and also to Lycia. A number of the reverse combinations (e.g. ΞΑ ΜΑ) were applicable to Lycia and seemed analogous to the true Lycian League coins with, e.g., ΚΡ ΞΑΝ or ΚΡ ΤΛ. 55 The error of accepting these coins as Lycian has persisted as recently as 1950, for Magie regarded them as evidence that Xanthus was briefly a member of the Masicytus district. 56

Hill's attribution of the coins to Caunus, 57 plausible politically although not yet the true attribution, has unfortunately been revived in the most recent and thorough publication of the series, by W. Sheridan in 1972. 58 Sheridan appears not to have grasped the arguments of A. Akarça, who in 1959 convincingly ascribed the coins to Mylasa. Akarça's reasons were that no finds of the coins have ever been reported from Caunus (or from Lycia, for that matter), while the six known provenances are all from the environs of Mylasa; and that an identical head of Helios with eagle across his cheek is found on silver coins, probably of the Augustan period, inscribed ΜΥ ΛΑСΕωΝ. 59 In any case, this pseudo-Rhodian series is emphatically not Lycian.

Sir Edward Robinson in 1914 published a silver drachm of another pseudo-Rhodian class, which he had acquired in Lycia. The coin was countermarked with a chimera, and he suggested that it had been struck and countermarked in Lycia during the period of Rhodian supremacy. 60 He noted a similar piece at the British Museum, whose countermark had previously been identified as a lion, 61 and a third example has since surfaced, from the island of Calymnos. 62 The beast of the countermark is remarkably similar in its stance to that of issue 1, with the lion head facing and the goat head reverted; and Robinson is undoubtedly right, as usual, that the countermark was applied in Lycia. It is less certain, however, that the coins were also struck in Lycia.

Several other silver coins, long known, seem to have been counter-marked by individual Lycian cities during the period of the League. A Rhodian drachm of the pre-plinthophoric series bears a stamp with a cithara bracketed by the letters ΚΥ, just as on the League silver of Cyaneae; and several tetradrachms of Side bear countermarks of a cithara and ΑΝ similarly arranged, evidently applied by Antiphellus. 63 These two cities issued very little League silver in Period II (Cyaneae is known from eight coins, Antiphellus from but one) and may have completed their contributions to the League with this counterstamped foreign currency. 64

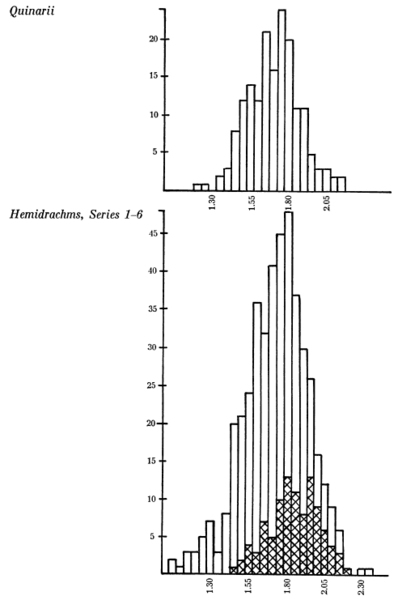

The earliest true Lycian League silver, however, that struck by the cities, consisted of drachms whose format echoes that of the plinthophoric drachms of Rhodes. The Rhodian obverses show a radiate head of Helios facing right; the Lycian ones a laureate head of Apollo facing right. The Rhodian reverses have the Rhodian rose in a shallow incuse square with, above, a magistrate's name written out in full, and, to either side, about half-way down the square, the two letters ΡΟ. The Lycian coins replace the rose with a cithara, also in a shallow incuse square, with, above, the federal ethnic ΛΥΚΙΩΝ, and, in the same locations as the Rhodian Ρ and Ο, the first two letters of the particular minting Lycian city. The Rhodian coins with this format were known in antiquity as plinthophoroi (πλινθοφόϱοι, as opposed to δϱάχμαΙ παλαιαί or old style drachms) and the Lycian ones as kitharephoroi (ϰιθαϱηφόϱοι). 65

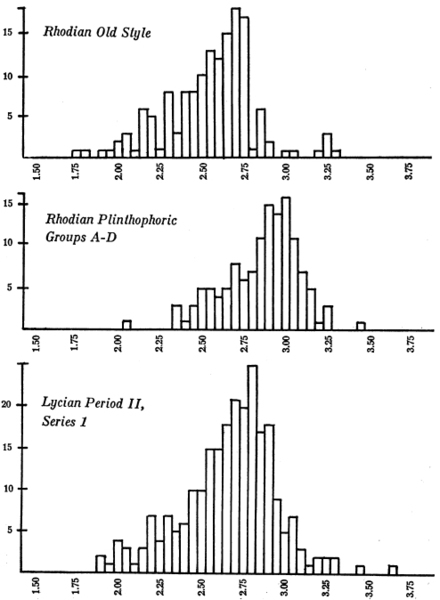

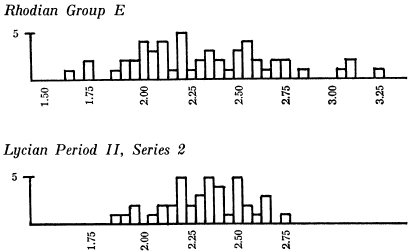

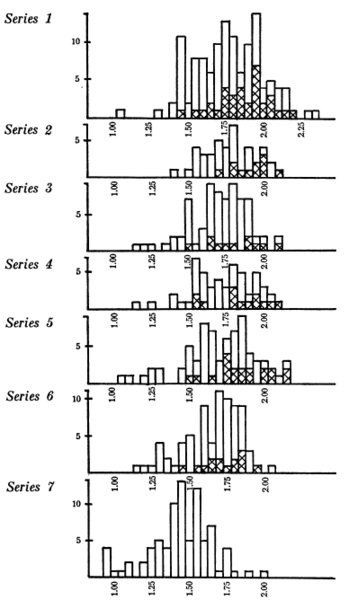

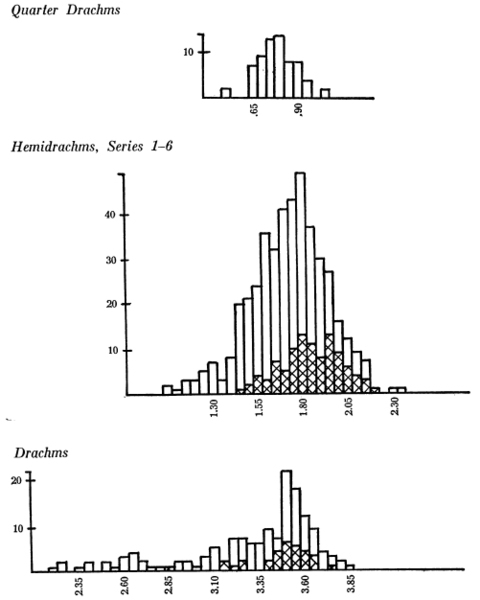

The Lycian drachms of Period II divide into three series: the bulk of the coins are in Series 1, with relatively small numbers in the later, reduced-weight Series 2 and 3. The original series, Series 1, is very close in its weights to the Rhodian plinthophoroi—at least to the full-weight plinthophoroi, for this coinage also in its final years included small emissions of reduced-weight coins. 66 Groups A-D, shown in Figure 2, are the large, full-weight plinthophoric groups.

The Rhodian plinthophoroi were struck to a standard noticeably higher than that of the old style drachms. 67 The weight of the Lycian coins of Series 1 is intermediate between these two, but must be understood as representing a standard very slightly reduced from that of the plinthophoroi. This slight reduction was generally the case among the many imitations of Rhodian coinage: the weights of the plinthophoric style coins of Carian Stratoniceia from the Muǧla 1965 Hoard, for instance, fall in exactly the same range as those of Period II's Series 1. 68

Late in 1970 a deposit reported to have consisted of some 200 Lycian League drachms was unearthed in Lycia. 69 One account gave the find spot as near modern Finike, on the southern coast; another, from probably a more reliable source, gave it as near modern Kemer on the eastern coast (not to be confused with another Kemer in western Lycia). The composition of the known portion of the hoard (133 coins, of which well over half are from the east coast cities of Olympus and Phaselis) confirms Kemer as the find spot. Only slightly over a hundred of the Rhodian-weight Lycian kitharephoroi struck by the cities were known before the appearance of this hoard, which has approximately doubled the number known of these civic coins of the League.

All the hoard coins were issues of the cities, with ΛΥΚΙΩΝ and city initials on the reverse; or, in the case of most of the coins of Olympus and Phaselis, with ΟΛΥΜΠΗ or ΦΑΣΗΛΙ replacing ΛΥΚΙΩΝ. Fourteen of the sixteen cities known to have struck League silver were represented, two of them for the first time. The hoard contained, however, none of the commonest League silver, that struck by the districts of Cragus and Masicytus, and none of the relatively rare city issues with the district issues' format (ΛΥ on obverse replacing ΛΥΚΙΩΝ on reverse).

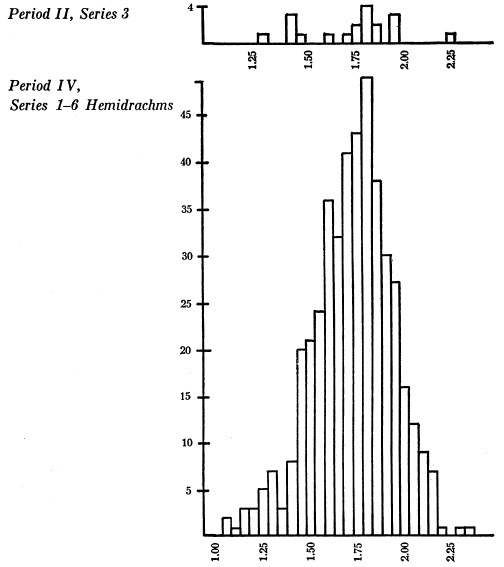

Virtually all of the hoard coins, furthermore, were of Rhodian weight, peaking at 2.80 grams (see Figure 2, above). Indeed, with very few exceptions, 70 all the previously known examples of League coins issued by the cities and bearing ΛΥΚΙΩΝ on reverse are of Rhodian weight. The Cragus and Masicytus pieces, on the other hand, most of which have ΛΥ on obverse, and all the civic pieces with the same format are struck to a lighter standard, peaking at 1.80 grams.

A basic distinction is to be made between the two groups of kitharephoroi. One group is the civic kitharephoroi with ΛΥΚΙΩΝ on reverse: these comprise the present work's Period II. The other group is the district kitharephoroi of Cragus and Masicytus, with which are to be classed the rare civic kitharephoroi with ΛΥ on obverse; these form Period IV. Both weight standards and the usual placement of the ethnic differentiate Periods II and IV.

Because the League silver has not been understood as comprising two separate groups, confusion has been the rule in most former treatments of their denominations. Hill in the BMC's catalogue calls the districts'—and Limyra's, for some reason—kitharephoroi drachms, but does not venture a denomination for the other mints' coins. Elsewhere in the BMC he calls the League's silver "drachms and hemidrachms (of degraded? Rhodian weight)." In the drachms he includes all the kitharephoroi, city and district; by hemidrachms he means the small district silver pieces with Artemis's head and quiver as types. 71 In still another place in the BMC he considers these smaller coins as half drachms or quarter drachms, and then lists them in the catalogue as quarter drachms, once with a question mark and once without. 72 Head in Historia Numorum repeats Hill's indecision, mercifully in shorter form, 73 and these two publications have been generally followed. The first work which has consistently distinguished the two classes of kitharephoroi is O. Mørkholm's publication of SNGvAulock, where the heavier coins are consistently called drachms and the lighter ones hemidrachms. 74

To return to the Kemer Hoard: through the kindness of many individuals in this country and in Europe it has been possible to collect a record of 133 of the reported approximately 200 coins. The coins reached various parts of Europe in separate lots, two of about 50 coins each, one of probably 30 or so, and the remainder apparently a few at a time. The known mints of the Period II drachms, the number of their coins previously known, and those known from the Kemer Hoard are given in Table 1. The mints are listed geographically from west to east, in order to facilitate later discussion; this is the order employed in the catalogue and in the discussion of individual mints. Table 1 also gives the number of obverse dies known for each mint in each of the three Series (1, 2, and 3) of Period II, both before and after the appearance of the Kemer Hoard.

All the coins of Period II have the same format, with ΛΥΚΙΩΝ and two city initials on the reverse. ΟΛΥΜΠΗ or ΦΑΣΗΛΙ, however, replaces ΛΥΚΙΩΝ on most coins of Olympus and Phaselis. Such coins of these two cities, without the federal ethnic, may be considered and are here termed, pseudo-League coins. The only true-League coins of Olympus and Phaselis are found in Series 1; their coins of Series 2 and 3 are all pseudo-League.

| Kemer Hoard | Other | Totals | |||

| Series 1 | Coins | Coins | Coins | Dies | |

| West | |||||

| Xanthus | 4 | 11 | 15 | 14 | |

| Sidyma | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1–2 | |

| Pinara | – | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Cadyanda | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | |

| Cadyanda or Candyba | 1 | – | 1 | 1 | |

| Tlos | 3 | 9 | 12 | 9 | |

| Patara | 4 | 18 | 22 | 19 | |

| South | |||||

| Phellus | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | |

| Antiphellus | 1 | – | 1 | 1 | |

| Aperlae | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Cyaneae | 5 | 3 | 8 | 6 | |

| Trebendae | 1 | – | 1 | 1 | |

| Myra | 18 | 18 | 36 | 22–23 | |

| Limyra | 8 | 24 | 32 | 18–19 | |

| Gagae | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Rhodiapolis | 7 | 11 | 18 | 5–6 | |

| East | |||||

| Olympus, true League | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |

| Olympus, pseudo-League | 26 | 7 | 33 | 17 | |

| Phaselis, true League | 5 | 1 | 6 | 3 | |

| Phaselis, pseudo-League | 35 | 19 | 54 | 32–33 | |

| Imitations | 2 | – | 2 | 2 | |

| 125 | 131 | 256 | 156–61 | ||

| Series 2 | |||||

| Limyra | – | 10 | 10 | 7 | |

| Olympus, pseudo-League | 4 | 14 | 18 | 11 | |

| Phaselis, pseudo-League | 4 | 9 | 13 | 12 | |

| 8 | 33 | 41 | 30 | ||

| Series 3 | |||||

| Cyaneae | – | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Limyra | – | 10 | 10 | 7 | |

| Olympus, pseudo-League | – | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Phaselis, pseudo-League | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| – | 19 | 19 | 16 | ||

| Totals | 133 | 183 | 316 | 201–6 |

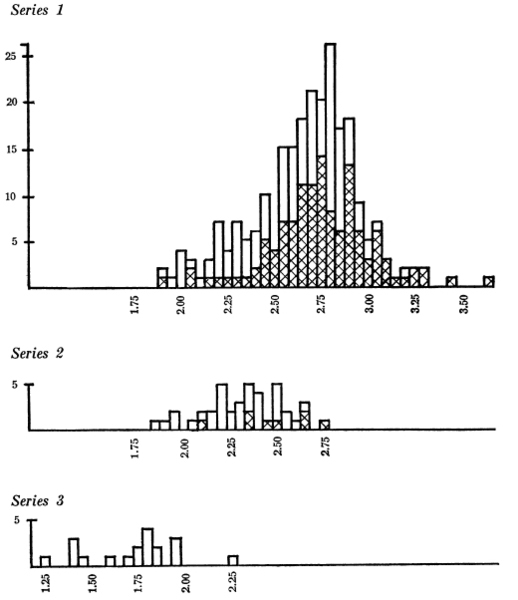

Series 1's coins, as noted above, are of Rhodian weight, or nearly so: just very slightly under the weight of the Rhodian plinthophoric drachms. Series 2 is noticeably reduced from Series 1; and Series 3 is still further reduced (see Figure 3).

Figure 4 shows the weights of each area (west, south, and east) within Series 1, and of each mint within Series 2 and 3. The Kemer Hoard has nearly doubled the number of coins known of Series 1, and added a few to the examples previously known of Series 2. It contained no coins of Series 3. That the geographical breakdowns within each series agree with each other confirms the validity of the division of Period II into the three series. This uniformity in weights is a new phenomenon for Lycia: Lycian silver in classical times had been struck to differing contemporary weight standards, the cities and dynasts of the west using a lighter standard than those of the south central region. 75

The Kemer hoard has provided the first silver coins known of Antiphellus and of Trebendae. It included the second known drachm of Sidyma, although no record was obtained of this piece and it has unfortunately dropped from sight; the third drachm of Phellus; and the third and fourth of Cadyanda (although one of these may instead be of Candyba, for which no other League coins are known). The only other known drachms of Cadyanda are also here published for the first time.

The Kemer Hoard also contained true League coins of Olympus and Phaselis, i.e. coins with the legends ΛΥΚΙΩΝ ΟΛ and ΛΥΚΙΩΝ ΦΑ, instead of these cities' usual markings of ΟΛΥΜΠΗ and ΦΑΣΗΛΙ. One true League coin of Phaselis has been for some years in a private collection, but unpublished; and one of Olympus in the Copenhagen cabinet was published in SNGCop in 1955, but in vain, for the coin has gone seemingly unnoticed ever since. 76

Several new issues of known mints also appeared in the hoard, and the large number of coins from the two eastern cities of Olympus and Phaselis has seriously altered the understanding of these cities' emissions. But the surviving proportion of all League Period II coinage is pitifully small. Only for one mint, Rhodiapolis, in Period II do the coins exceed two per obverse die, and only for a handful of other cities do they even approach two. For all of Period II, leaving aside the five hoard coins reported but not recorded, there are known 311 coins from 201 dies, a ratio of almost exactly 1.5 to 1. Clearly the known material represents but a mere fraction of the original output, and any conclusions drawn from the surviving material must be regarded as tentative.

| a |

Brackets to the left indicate obverse die identities; dotted brackets to the right indicate cases where the reverse initials

of one city

have been cut over those of another. See discussion after Xanthus. "Pseudo-League"

coins are those without the federal ethnic, ΛΥΚΙΩΝ. Indefinite numbers of new dies result from specific reported hoard coins

of which no

cast or photographic record could be obtained, and of which the dies are thus not known. Die totals are of course reduced

by the number

of shared dies. A number of coins in trade since 1970 are quite possibly, even probably, from the hoard but are not here or

in the

catalogue called hoard coins in the absence of specific evidence.

|

| a |

Shaded areas indicate Kemer Hoard coins.

|

| a |

Shaded areas indicate Kemer Hoard coins.

|

| 66 |

For discussion of the Rhodian plinthophoric drachm groups, see below, pp. 81–84.

|

| 67 |

R. H. J. Ashton has kindly pointed out (private communication) that the old style drachms were of substandard

weight, weighing considerably less than the appropriate fraction of the contemporary old style didrachms and tetradrachms;

and that even

though the plinthophoroi are somewhat heavier than the old style drachms, they still were struck to a reduced standard in

terms of those

didrachms and tetradrachms.

|

| 68 |

H. von Aulock, "Zur Silberprägung des karischen Stratonikeia," JNG 1967, pp. 7–9 (

IGCH 1357).

|

| 69 |

The hoard is mentioned in

Gordian

, pp. 34, 37, 47, and 52; it is no. 96 in Coin Hoards 1.

|

| 70 |

These exceptions form Series 2 and 3, in contrast to Series 1 of Rhodian weight.

|

| 71 |

P. xxii. The Artemis-head pieces are indeed the half denominations of the

district kitharephoroi but bear no relation to the heavier civic drachms.

|

| 72 | |

| 73 |

HN

2, p. 693.

|

| 74 |

His division of the two classes in SNGvAulock is nearly perfect; he recognizes that the lighter civic coins (nos.

4318 and 4365) are to be classed with the district issues, but calls no. 4325 (an unusual heavy coin, with only Μ for mint

identification) a drachm of Masicytus rather than of Myra. Still, Mørkholm seems to be the first scholar to have recognized that

the kitharephoroi fall into two distinct groups.

|

| 75 |

Mørkholm, pp. 65–76.

|

French excavators at one of the major Lycian sanctuaries, the Letoön near Xanthus, unearthed in the summer of 1975 a deposit under the cella of one of the sanctuary's temples. The hoard is the first containing Lycian League material to have been found under controlled conditions, and it is the first to contain another coinage together with the League's. The coins were found over a limited area under the cella floor, or more accurately in the earth under where the floor had been, for the blocks had been removed in late antiquity. The following brief summary is based on a provisional account of the hoard, written before all the coins had been properly cleaned and identified. 77

The hoard contained about 30 bronzes and about 50 silver coins. Identified silver coins are three kitharephoroi of the League with reverse legend ΛΥΚΙΩΝ, hence probably city coins of Period II; eight Rhodian drachms, both old style and plinthophoroi; 41 Rhodian triobols (the only two described are plinthophoric); and at least one pseudo-Rhodian drachm (the last coin described, erroneously called a hemidrachm). The only bronze coins described are three small ones of Xanthus as issue 60 in Period III, below. 78

Clearly none of the Letoün Hoard coins are included in the present study, and it would be premature to speculate on the hoard's date or significance without fuller knowledge. It is mentioned here only for completeness.

| 76 |

SNGCop 111; cf. Mionnet, Suppl. 7, p. 17, 69. Overlooked, for example, by

Jones: "It is curious that the coins of Olympus, though of

federal type, never bear the name of the federation" (p. 102), and by von Aulock, who is at least aware of the

Mionnet entry (

Gordian

, p. 34). Waddington and Warren, however, appear to have seen true League coins of

Olympus (Asie Mineure, p. 113; Warren,

p. 42).

|

Our chief literary source for the Lycian League is Strabo. In the midst of his

geographical account of the country, he says of the League: There are twenty-three cities which share the vote. The Lycians come together

from their various cities to their congress (συνέδϱιον), at whichever city they have selected. Each of the largest

cities controls three votes, the medium-sized two, and the others one. In the same fashion they pay their contributions and

perform other

liturgies. Artemidorus said that the six largest cities were Xanthus, Patara, Pinara,

Olympus, Myra, and Tlos …. At the congress first they choose the Lyciarch and the other officials of the League, and

appoint common courts of justice. Earlier they used to decide about war and peace and alliances, but now they do not, of course,

as all

such things by necessity are settled by the Romans …. Similarly, judges and magistrates are elected from the cities in proportion

to their

votes.

79

And near the end of his treatment of Lycia, Strabo says of Phaselis: "Now this city too is Lycian … but it has no part in the common League and is a separate organization to itself." 80 The floruit of Strabo's source, Artemidorus of Ephesus, was in the 169th Olympiad, 104–100 b.c., and this gives us the valuable information that at the very end of the second century b.c. the six most important cities were Xanthus, Pinara, Patara, and Tlos in the west, Myra in the south, and Olympus in the east. Phaselis, however, was not then a League member.

The names of these six cities are capitalized in Table 2, which gives a brief summary of the several types of evidence for the nineteen Lycian cities which coined for the League, and for a twentieth, Candyba, which may have coined. Most of these cities minted the silver drachms of Period II, while two (Telmessus and Arycanda, italicized) are known only from later issues. Among the cities striking the civic bronzes of Period III, only Arycanda is not yet known in silver. Drachms of Arycanda may yet appear, for drachms of several other cities are known from only one coin or from a very few.

Columns 1–4 of Table 2 give the League coinages of the twenty cities: column 1 shows the drachms of Period II and column 2 the civic bronzes of Period III. Columns 3 and 4 give silver and bronze struck during Periods IV and V in the names of the cities, although the bulk of the coinage struck in those periods was, of course, in the names of the districts, with only occasional issues bearing city initials. Many of the League cities also struck autonomous coinages, some quite possibly contemporary with League issues; these are not included in this study.

| League Coinage | Literary Sources | Inscriptions | Gordian III Coins | |||||||

Per. II

|

Per. III Æ |

Per. IV

|

Per. V Æ | Strabo | Pliny | Ptolemy | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||

| West | ||||||||||

| Telmessus | ? | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| XANTHUS | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Sidyma | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| PINARA | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Cadyanda | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| TLOS | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| PATARA | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| South | ||||||||||

| Candyba | ? | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Phellus | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Antiphellus | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Aperlae | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Cyaneae | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Trebendae | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| MYRA | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Arycanda | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Limyra | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Gagae | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Rhodiapolis | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| East | ||||||||||

| OLYMPUS | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Phaselis | x | x | x | x | x | x |

Columns 5–7 give the occurrences of the minting cities in the three chief geographical treatments of Lycia: Strabo, 81 who wrote in Augustan times but whose account was based on the earlier work of Artemidorus; Pliny, 82 from the late first century a.d.; and Ptolemy, 83 from the middle of the second century a.d.

Roughly contemporary with Ptolemy or perhaps a bit earlier was an extremely rich Lycian citizen named Opramoas: a long inscription from his native city of Rhodiapolis lists the cities which benefited from his donations. This inscription, supplemented by a few others in TAM, provides the inscriptional data shown in column 8 for all the cities except Trebendae and Candyba. These two, however, occur in a contemporary inscription listing the cities honoring the Lyciarch Jason of Cyaneae. 84

Lycia as a Roman province coined under Claudius in a.d. 43 (see Appendix 3), and under Domitian, Nerva, and Trajan in the brief period a.d. 95–99, but these strikings bear no indication of mint. Lycia's final ancient coinage was an isolated and rather surprising outburst of Imperial bronzes in 242–44, under the young Gordian III and his wife Tranquillina. Twenty cities struck this coinage; the fourteen that correspond to the League mints are shown in column 9.

This tabular form should be more useful, and certainly is more compact, than a textual description, city by city, with all these bits of evidence. Von Aulock's recent compilation and study of the coinage of Gordian and Tranquillina includes for each of their minting cities an excellent summary of its geographical, inscriptional, and numismatic evidence. 85 For many of the League cities, the inscriptions have been conveniently collected in TAM, which includes the inscriptions from the western mints, Arycanda and Rhodiapolis among the southern mints, and both the eastern mints.

Several cities which in the past have erroneously been ascribed League coinage are discussed in Appendix 1.

| a |

Period II silver mints are in Roman letters, and Strabo's six largest cities

are in capital letters. Italic letters indicate cities whose coinages are only known later than Period II.

|

| 77 |

E. Hansen and C. Le Roy, "Au Létôon de Xanthos: les deux temples de Léto," RevArch 1976, pp. 321–25. I am obliged to M. Mellink and H. Metzger for having put me in

touch with M. Le Roy, who was directly responsible for the excavation of the temple where the hoard was found. I am

much indebted to M. Le Roy for his long and extremely helpful letters on the subject of the hoard, which he expects

will be published by O. Picard.

|

| 78 |

Hansen and Le Roy (above, n. 77), p. 324, n. 1.

|

| 79 |

14.665.

|

| 80 |

14.667.

|

| 81 |

14.664–67.

|

| 82 |

NH 95–96 and 100–101.

|

| 83 |

Geog. 5.3.

|

| 84 |

TAM 905 (Opramoas) and IGR 704 (Jason).

|

| 85 |

Obverse dies are numbered within each issue. Individual dies are referred to on the plates and in the discussion by issue number followed by die number: thus 8.3 indicates the third obverse die of issue 8.

Illustrated coins are marked with asterisks. When more than one coin from one obverse die is illustrated, the illustrations follow the order of the catalogue. Every obverse die is illustrated. Unknown obverse dies are indicated in the catalogue by an x.

The reverse dies found with each obverse die are shown by lower-case letters (a, b, c) following the obverse die number; these lower-case reverse letters are not repeated on the plates. Brackets to the right indicate reverse die identities.

Relative die axis positions are not given, as the great majority are ↑↑, with the few variations either ↑↗ or ↑↖.

(Kemer) indicates that the coin is from the Kemer 1970 Hoard.

Mints are listed in order from west to east, and commentary on each mint follows its catalogue. General commentary follows Series 3.

Drachms:

Obv. Laureate head of Apollo r.; behind shoulder, usually, bow and quiver.

Rev. ΛΥΚΙΩΝ above and city initials to either side of cithara; all in shallow incuse square (the inscriptions vary on the pseudo-League and imitative issues 42–45 and 47–49).

Xanthus 15 coins, 14 obv. dies, 15 rev. dies

5. Rev. ΞΑ (Ξ alone on 5.10a).

5.1 = 6.1 (Sidyma). It is not clear which city's coins were struck first.

5.2 = 8.1 (Cadyanda). The die's slight deterioration (spreading lines in the field present only on the Cadyanda coin) shows that Xanthus's coin was the first struck.

Xanthus lies on a high plateau over the Xanthus River, some eight miles north of the southern coast of Lycia. Xanthus's remains are the most extensive and impressive in Lycia; from it come the Nereid monument and other remarkable sculptured tombs now in the British Museum. And Strabo, speaking of ca. 100 b.c., says that Xanthus was, besides one of the six cities controlling three votes each in the federal assembly, "the greatest city in Lycia." 86

It is therefore somewhat surprising that but 15 of the 316 coins of Period II are of Xanthus. But as these 15 are struck from 15 reverse and 14 obverse dies, of a variety of styles, it is clear that the surviving material is a poor guide to the original size of Xanthus's League coinage. Most of the drachms of Period II presumably were melted down for recoining as the lighter district issues of Period IV; any surviving today must have been lost or buried before the change in standard. The Kemer Hoard, for example, buried in eastern Lycia just as the coins' standard started to fall, has expanded the known Period II Series 1 coinage of Olympus from 8 to 36 examples. A hoard of similar date from the west could well do the same for Xanthus.

What is remarkable, however, given the meager amount of material available from Xanthus and the three other Xanthus Valley cities of Sidyma, Pinara, and Cadyanda, is the amount of die linkage connecting these cities. Two Xanthus coins share an obverse die and the two Pinara coins a reverse die: this is all the intra-city linkage provided by the 21 coins of these four cities. But there are three inter-city obverse links: Xanthus-Sidyma, Xanthus-Cadyanda, and Pinara-Cadyanda; and there are also two cases of recut reverses, from coins other than the obverse-linked ones: Cadyanda cut over Xanthus, and Pinara also cut over, most probably, Xanthus. A schematic portrayal of these relationships follows. The cities' positions correspond to their geographical locations, Cadyanda being the northernmost and Xanthus the southernmost. The arrows point towards the second users, when known, of the particular dies. The recuttings are self-explanatory, and the Xanthus-Cadyanda and Pinara-Cadyanda dies have broken down somewhat by the time of their use by Cadyanda.

The recutting of Xanthus's reverses for Pinara and Cadyanda, together with the shared obverses and strong similarities between other obverses of the four cities, shows that Xanthus was probably the source of all four cities' dies. But once again the vexing question of central mint or travelling dies arises. Three possibilities present themselves: Xanthus sent out dies to each of the other three cities separately; it sent out one group of dies which went in turn to each of the other cities; or it struck all the coins itself. The obverse link between Pinara and Cadyanda rules out the first possibility. The second, one traveling group of dies, is not disproved but is indicated as unlikely by the fact that the Sidyma reverse is not a recut one. A traveling group of dies would presumably have gone first to Sidyma, then to Pinara, and finally to Cadyanda, the farthest town from Xanthus. It seems unlikely that the mint workmen would have cut a fresh reverse for use at Sidyma while saving used Xanthus reverses for later recutting at Pinara and Cadyanda—especially as Sidyma's Σ would have covered Ξ so much more easily than would Pinara's Π.

Therefore it seems probable that all the coins of the four cities were struck at Xanthus. That the die breaks and recuttings all show Xanthus as the dies' first user need indicate only that the home city's required coinage was struck first, which is after all what one would expect.

It is interesting to note that, although Patara and Tlos in the west minted under Gordian, none of these four die linked cities of Xanthus, Sidyma, Pinara, and Cadyanda did. (The only other Period II mint missing from Gordian's mints is the insignificant Trebendae.) Whatever the nature of the bond between the four cities here discussed, it evidently was an enduring one.

Sidyma 2 coins, 1–2 obv. dies, 1–2 rev. dies

6. Rev. ΣΙ.

6.1 = 5.1 (Xanthus). It is not clear which city's coins were struck first.

The reverse die used with 6.1 is not recut. Although a Σ could easily cover a previous Ξ, and the Ι is tilted somewhat, there is no trace whatever of a previous letter under the Ι, and, with the cithara off-center to the right as it is, the space would hardly have been large enough for an Α.

The coin struck from 6.x was reliably reported to have been in the Kemer 1970 Hoard, but no record was made of it, and its dies are unknown.

Sidyma lies on the southwestern slope of Mt. Cragus, west of the Xanthus River, and some eight or nine miles northwest of Xanthus. Sidyma's remains from pre-Roman times are not extensive.

The single drachm here catalogued, first published in 1902, is the only known coin of the city. A second League drachm from the Kemer Hoard has unfortunately dropped from sight. Sidyma's drachms seem to have been struck at Xanthus. 87

Only four of the 16 cities represented in Period II are missing from those striking the civic bronzes of Period III. The absence of two, Olympus and Phaselis, is probably significant and will be discussed below. But that no small bronzes of Sidyma or of Rhodiapolis have yet appeared is probably due to chance.

Pinara 2 coins, 2 obv. dies, 1 rev. die

7. Rev. ΠΙ, cut over Xanthus.

7.1 = 8.2 (Cadyanda). It is not clear which city's coins were struck first.