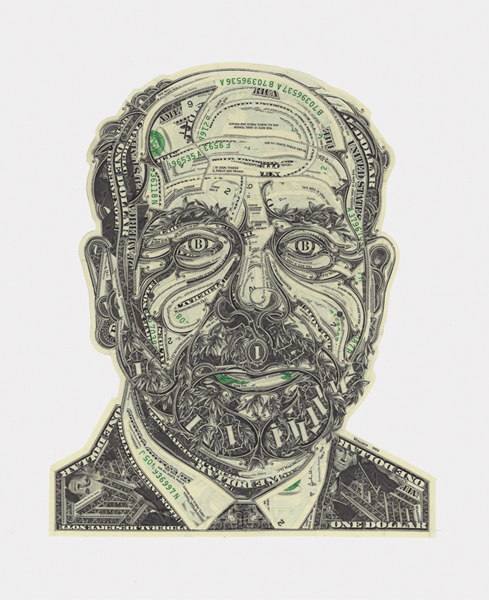

Artist Mark Wagner is Reinventing the US Dollar Bill

Visual Artist Mark Wagner exclusively uses US dollar bills in his work, and has done so for decades. From creating collage-style portraits, still lives, and sculptures to an actual money tree, Wagner attempts to meticulously use every detail of the banknotes he works with. Wagner’s humorous, approachable, and culturally relevant pieces have made him a favorite of the New York City art world and beyond.

Over the years, Wagner has continued to create subversive works that offer a larger social commentary on money, economics, and beyond. In 2009 he constructed a 17’ x 3’ recreation of the Statue of Liberty entitled Liberty, made from pieces of over 1,000 dollar bills. Several of Wagner’s other works including, FROM DARKEST DECAY was featured at the Expo Chicago in September and his other work, CUT UP CUT CUT is on view at the Bellevue Arts Museum and will be traveling as part of a group exhibition through 2009. We sat down with Wagner to discuss his relationship to money, how he obtains the bills he uses in his work, as well as the larger personal and political underpinnings that fuel his art.

ANS: What first attracted you to working with money?

Mark Wagner: I’ve always been a sucker for paper culture—for different printing methods and graphic design styles, as well as different methods of illustration and text presentation. Everything from fine art printing, to common stuff like packing materials, and paper napkins. In the ’90s I’d been doing a lot of collage from a bunch of different materials, anything I could get my hands on. I always had a large supply of Camel Cigarette wrappers because a couple friends saved them for me. There was something about the familiarity of the package that made those collages effective, especial to Camel smokers. So, I tried to think of other popular pieces of paper I could use and settled on the single most popular piece of paper on the planet: the US One Dollar bill.

At first I loved the dollar bill for material reasons—it was readily available, the paper it’s printed on is super sturdy, more durable than literally any piece of paper you can buy from an art supply store; the printing on it is super fine, and anything you make from it is immediately familiar to the viewer on a subconscious level. It started to dawn on me what it meant to use MONEY. That money is not some neutral thing, it’s not like cutting up bus tickets or playing cards at all. That everyone has money issues and that addressing those issues with this material could make for some pretty OK art.

ANS: What is your process like in conceptualizing a piece and then getting the materials needed to create it?

MW: I’m always processing materials. I’ve got an assistant who helps me as well. We break down bills into rudimentary parts and build these up into shapes, textures, and passages that might be useful in the future—Bins of head parts, a binder full of constructed trees and other plant life, little hands, little birds, little figures of George Washington. Then I work from the other end as well. Drawing sketches and figuring out how I can deploy these “moves” to greatest effect. How I can use money to say something about money or sometimes just make something pretty.

ANS: How do you obtain the money used in your pieces?

MW: I get stacks of crispy ones directly from the bank when they have them. Sometimes I set aside crispy bills I receive as change. I like the small portrait bills from the 90s for the larger US denominations; usually I buy these on Ebay.

ANS: What is your attitude towards money?

MW: Money is basically a form of magic. Here is a substance I can transform into any other substance. That money and all our attitudes about money are a funny amalgam/chimera of everything money has ever been in the past. It is part honor-exchange, part commodity, part bank draft, part debt. Our last clear foci of money was as an amount of metal: here is a quantity of gold that can be exchanged for a quantity of some other substance. Or new foci, I think, will be more like the electricity inside a battery—here is a quantity of power I can use to perform an amount of work.

ANS: What are some of the broader themes you explore in your work in relationship to wealth and capitalism?

MW: I prefer subject matter that has a direct link with the materials. I use US bills for the most part anything Americana, American identity, or Founding Father-ish. I do portraits at least in part because of coin and currency addiction to portrait busts, sometimes the portraits are representations of some sort of human “value” trying to reclaim that word from its fiduciary use.

There are lots of representations of wealth in the work, architecture, leisure activities, lavish gardens, artworks. Concentrations of wealth have given us both some of the most beautiful things in our culture, as well as gross examples of decadence. There are lots of barriers and dividing lines depicted in the work—fences, hedge, walls. There’s a fair amount of menace. And there’s no shortage of both mystery and mythology. The thing is, I could represent anything out of money and it would seem like I was on topic and making a statement. If I depicted, say, the coffee cup sitting in front of me it would seem like I was commenting on the prices at Starbucks.

ANS: Do you think there is a gendered component to the work you create? And if so, what do you think that is?

MW: I hadn’t thought about this until you asked, but of course there is. There are no women on US bills I can easily cast as characters in my work. And money itself is probably considered a masculine thing. I do think the patience of execution harkens back to my Mom sewing, though. Quilts and embroidered samplers have informed my work as well as cropping up as subject matter.

ANS: What are some current projects you have in the works, and do you have any upcoming exhibitions?

MW: I’m just finishing up a 6’ x 4’ money tree. I’m making some dollar bill “Loan Ranger” masks. I’m making some portraits of at-risk children from Ghana. I’m working on a couple of essays about the nature of money and art. I’m working on plans for a 12’ x 18’ collage of movie monsters battling over New York City.

ANS: Do you collect any coins or other currency beyond $1 bills?

MW: Yes, mostly in a catch-as-catch-can manner. My coin collection started as a kid with a jar of European coins that my dad had brought back decades earlier from World War II. I came from a small town in rural Wisconsin, and I loved the connection to another place and time.

As a kid I loved—and still love to this day—a few of the coins from the jar, which had circulated for well over 100 years, worn almost completely smooth: Napoleon’s name, or one of the George’s only barely visible. I still have the US silver quarter and about a 1/4 of it worn away that I used for silver-point drawing in art school. I still have the silver quarter I was handed as change at the deli, that I recognized first by the unfamiliar, deeper note within the handful of jingle. I love the beautiful face on the Mercury dime and the oddness of the fasces on the back. I love the weight of the Franklin half-dollar which is judged most comfortable for practicing my finger rolls and palming.

I’ve got a small collection of paper currency. People know I like money, so they give me unwanted currency left over from their foreign trips. And I’ve got a small collection of late 19th, early 20th century stock certificates I love for the art and design’s sake—the decorative borders, the classicism meeting anachronistically with technology and modernism, all the rubber stamps and signatures and cancellations.

ANS: Have you run into any legal issues with cutting up US currency? If so, what happened and how did you resolve it?

MW: No legal issues so far. I think it’s pretty clear there’s no fraudulent intent in what I’m doing. I’m hurting no one. I’m generating a fair amount of economic activity, tax revenue, and seigniorage through my actions. I’m naughty, but safe-naughty.

ANS: Do you view your work as subversive and are there any political underlinings to your current work given the current administration?

MW: Subversive, I’d like to think so, but then again maybe I’m just commodifying my own dissent. My first reaction to the new regime art-wise was to try to ignore it. I’m still on that tack, trying to make pretty things or timeless things or the same sort of things I would have made a couple years ago.

Before the election I made a portrait of Trump for an art show. It hung in a voting booth next to a portrait of Clinton back in September of 2016. After the exhibition (but before the election) I burnt the Trump portrait because I’d really come to detest the man.