The Wildcat Bank of Brest

The Bank of Brest in Michigan was one of the most infamous “wildcat” banks that sprang up amidst the more freewheeling economic environment that took hold during the Market Revolution in the United States. Wildcat banking encompassed a broad array of dubious practices that banks indulged in during the state-chartered era of banking. It most commonly referred to banks established in out of the way locations that flaunted regulation and issued bank notes in large quantities without any intention of ever redeeming them. Although there were state regulations and commissioners, enforcement was often lax and as we will see, wildcat banks constantly came up with creative ways to circumvent the law.

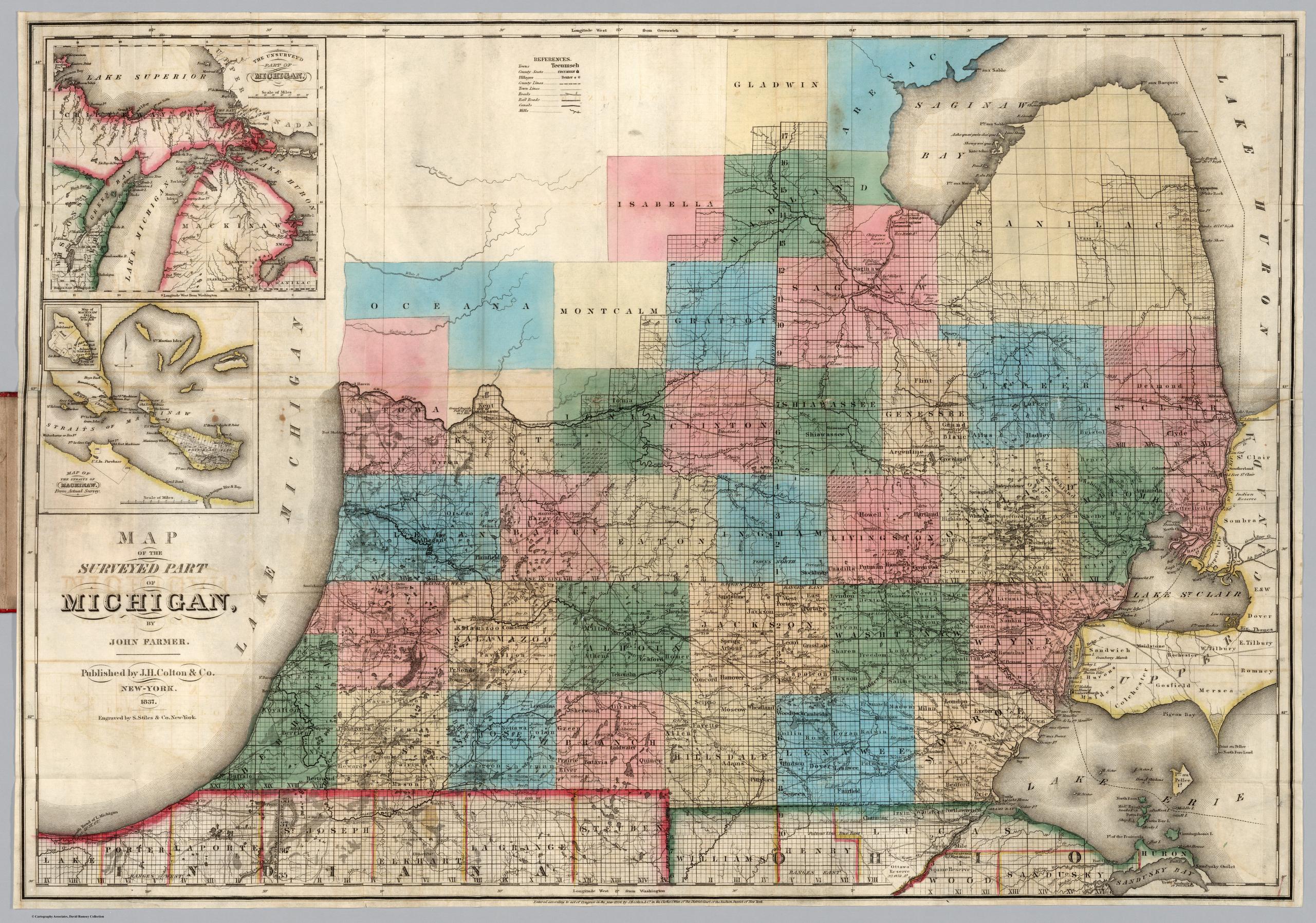

Michigan was admitted into the Union on January 26, 1837, as the 26th state. There was a strong sentiment in the new state for “free banking,” which sought to extend the privilege of banking beyond the elite and politically connected. The legislature duly passed “An Act to Organize and Regulate Banking Associations” that significantly loosened requirements and oversight of banks. It allowed any twelve ‘freeholders’ who wanted to start a bank to simply notify the Secretary of State, open books for subscription, and commence operations when thirty percent of the capital stock had been paid in specie (in practice the bar was even lower). The act was signed into law by the “Boy Governor,” 25-year old Stevens T. Mason, on March 15, 1837, and Michigan became a forerunner of the free banking experiment.

When the legislation passed there were sixteen chartered banks operating in Michigan; a year later there were more than fifty. This was due in part to the effects of the Panic of 1837, which among other things led people to hoard hard money and made it very difficult for banks to redeem their notes with specie. In June, the legislature passed a measure that allowed banks to suspend specie payments, i.e. they were no longer required to redeem paper notes with hard money (gold and silver). The loosening of specie requirements only encouraged more dodgy characters and banking ventures.

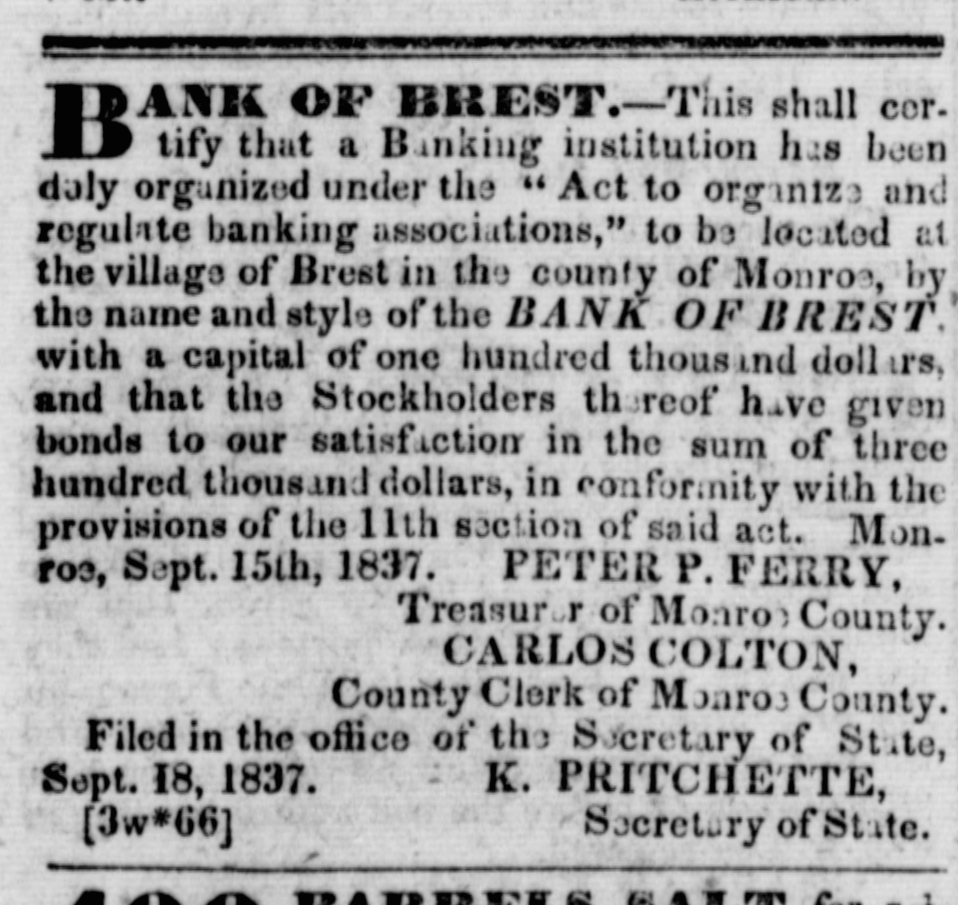

Among those joining the rush was the Bank of Brest, which announced its incorporation in September 1837 with a notice that appeared in papers around the state. Brest was a hamlet located about forty miles from Detroit on the shores of Lake Erie (present-day Newport, MI). The fact that Brest now had bank would have been rather surprising news to those in the know. In Banks and Banking in Michigan (1887), Theodore Hinchman sarcastically described the “city” as follows:

The City of Brest was on the lake road to Monroe, in that county. A trip in the fall of 1838, on horseback, discovered the palaces of ” rag barons ” to consist of a very small hotel, a store, and a bank building, costing $1,711. There were also included in this category hundreds of city lots for sale in currency of any kind. The population was myriads, consisting, unfortunately, of mosquitos. Large fires were built about the tavern to determine whether the guests should eat or be eaten, and whether the hum of the busy and musical denizens should disturb their sleep. They were the natural guardians of the untold gold that the bank vaults were supposed to contain. No one visited that place twice in pursuit of gold or a gold mine. At this date the city lots are not sold, and but for its banking history the city would be unknown.

Perhaps the biggest clue as to the bank’s true purpose was that it began issuing bank notes even before its notice of organization was filed with the Secretary of State. It was capitalized by a combination of paper assets (real estate, personal checks) and $10,000 in specie provided by Lewis Godard, something of a wildcat banking king who simply shifted this same reserve of specie to the many different institutions around the state he had a hand in. On this meager security, the Bank of Brest was able to issue over $200,000 in bank notes before state authorities caught up to the scheme. An audit in August 1838 that was part of a larger crack down on the orgy of speculation and chicanery led to the bank being shut down. By the end of 1839, there were just seven banks in operation throughout the state, but over a million dollars of worthless currency in circulation.

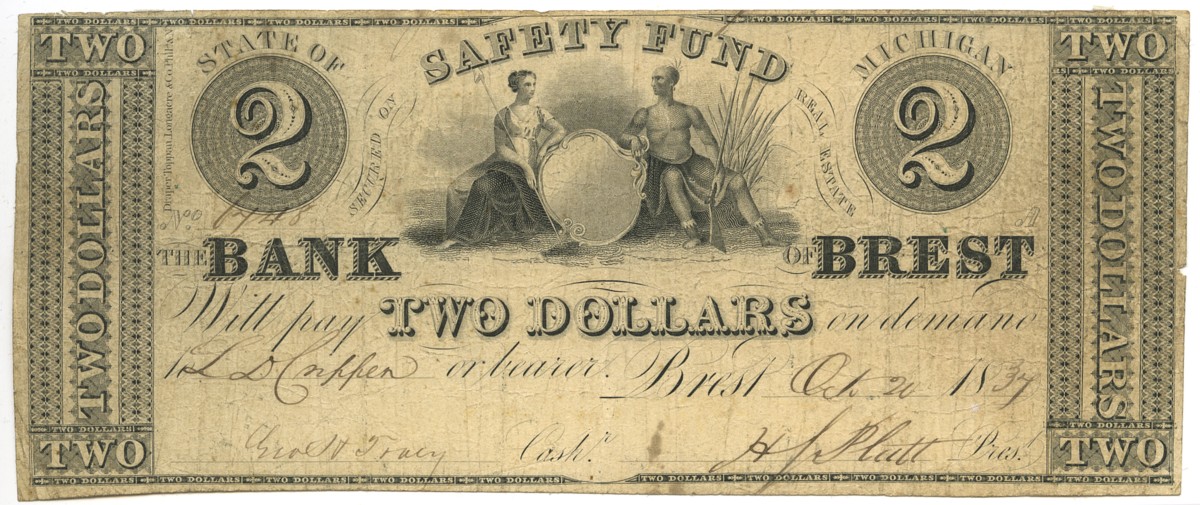

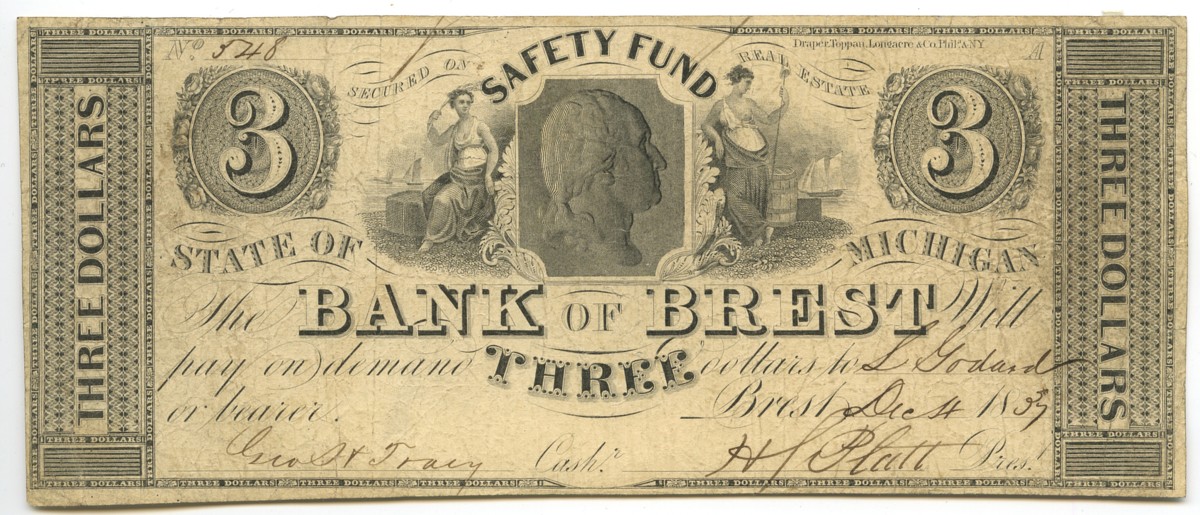

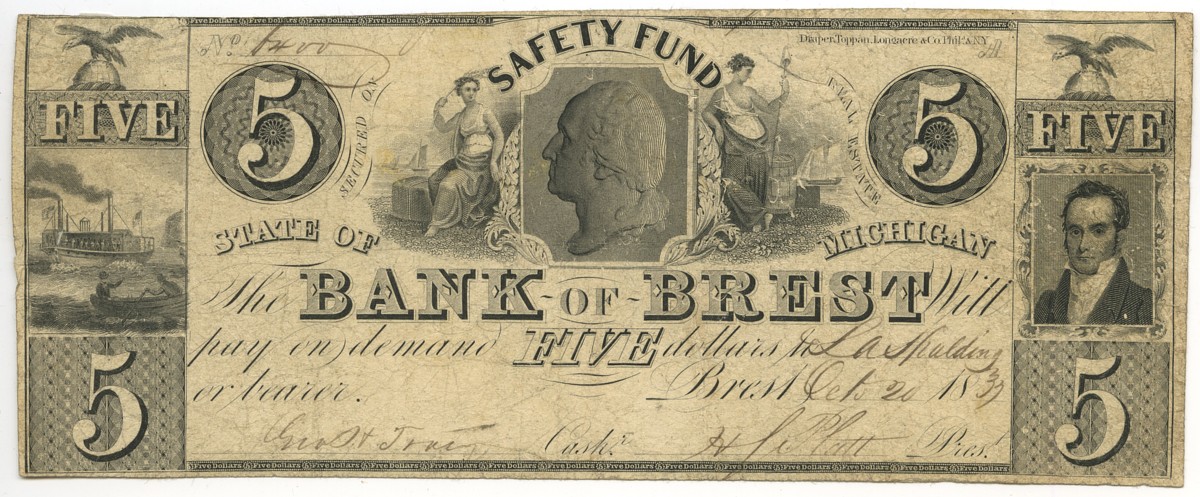

A good portion of that was from the Bank of Brest, which issued notes notes in $1, $2, $3, and $5 denominations. They were printed by Draper, Toppan, Longacre & Co. of Philadelphia, and they are rather attractive notes for their time. With well-cut vignettes, elaborate counters, and other security features, the bank notes at least conveyed an air of legitimacy.

All of the notes were pen numbered and dated, and signed by the cashier George H. Tracy and the president Henry S. Platt. Given the volume that the Bank of Brest printed over its short life and the fact that almost none of it was able to be redeemed, these are fairly common among collectors of obsolete bank notes. But they are also a wonderful bit of Americana, and a reminder of an era when banks ran wild in the Great Lakes State.

For more on the wildcat banking era in Michigan see, T. H. Hinchman, Banks and Banking in Michigan (1887); Gerald P. Dwyer Jr., “Wildcat Banking, Banking Panics, and Free Banking in the United States” (1996); Harold L. Bowen, State Bank Notes of Michigan (1956).