The Poor Widow’s Mite

Every year at Christmas time, I seem to see mentions of the “poor widow’s mites” made famous by the story in Mark 12:41-44 (and also in Luke 21:1-4):

And Jesus sat over against the treasury, and beheld how the people cast money into the treasury: and many that were rich cast in much. And there came a certain poor widow, and she threw in two mites (λεπτόν), which make a farthing (κοδράντης). And he called unto him his disciples, and saith unto them, Verily I say unto you, That this poor widow hath cast more in, than all they which have cast into the treasury: For all they did cast in of their abundance; but she of her want did cast in all that she had…

The word “mite” first appears in the books of Mark and Luke in the 1525 publication of Tyndale’s New Testament, where it was likely intended as a shortened version of the word “minute” and not as the name of a denomination. As the late Fr. Augustus Spijkerman has noted, the word lepton “implies very small coins…even we may say…the smallest coin being in circulation in Palestine at the time concerned.”

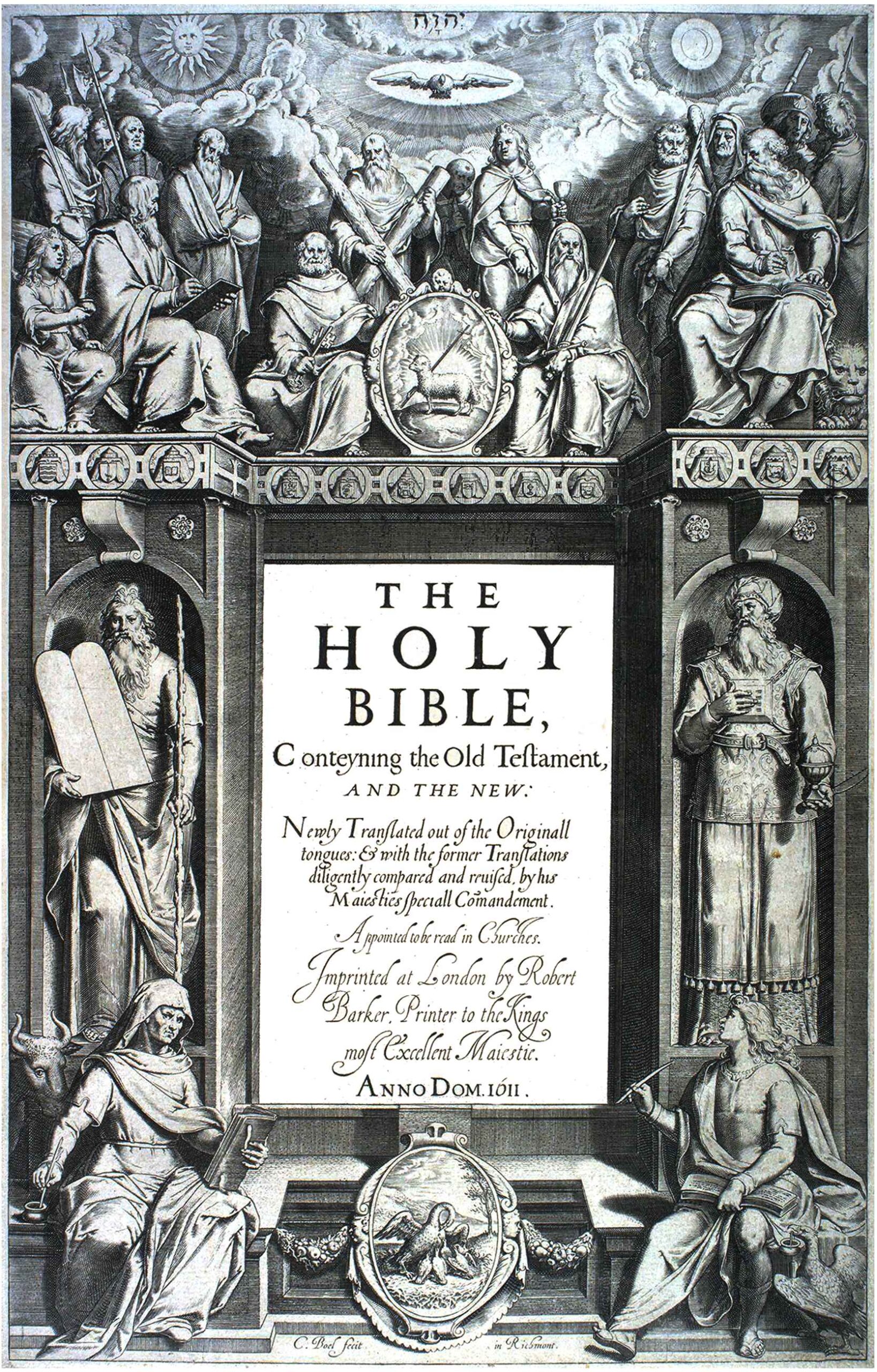

Oliver Hoover has noted that it is not surprising that scholars who made the early English translations of the Bible had a tendency to “reinterpret the ancient coin denominations of the Greek, Latin, and Hebrew scriptural sources in terms of contemporary sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English money.” Hoover, who discussed this in detail for an article in the ANS Magazine, points out that neither the original Greek text of the New Testament nor the Latin Vulgate Bible mention the “mite.” Instead the Greek or Latin words used in that version are, respetively, lepta or minuta.

The word “mite” was most widely disbursed by the authoritative King James version, which was printed in 1611 after work by dozens of scholars over nearly seven years. It became the most popular English version of the Bible ever published and it was noted for its scholarly translations and the artistry of its language, which influenced the course of English literature. In the preamble, the translators expressed the hope that the work would “speak like itself, as in the language of Canaan, that it may be understood even of the very vulgar.” In his article, Hoover observes that early English translations of biblical texts are of “some interest to numismatists, given their tendency to reinterpret the ancient coin denominations of the Greek, Latin, and Hebrew scriptural sources in terms of contemporary sixteenth and seventeenth-century English money.” In numismatic terms, the King James Bible can often tell us as much about the the circulating coinage of early modern Great Britain as it does that of the ancient world. However, there was no mite coin known to exist in British coinage of this period.

Hoover notes that the mite (meaning “small cut piece” in Old Dutch) only began circulating Flanders in the early fourteenth century. The early example below is billon, but by the sixteenth century, it was being minted in copper.

ANS, 0000.999.7906

One might guess, therefore, that this denomination was imported and used in Britain at the time, but there is little evidence to support that possibility. Even though the Dutch mite did not circulate in Britain, and no British mites existed per se, it was mentioned in contemporary arithmetic books as a fraction of a farthing, varying from one-third to one-sixteenth.

Given all this, Hoover concludes that it seems likely that the mite entered into the King James Version “as a result of a translational quandary created by the original.” In the early English translations, the Gospel of Mark gives the value of two lepta as a kodrantes or quadrans. The crux of the matter for Hoover is that “any Latin grammarian would have known that a quadrans was a bronze coin worth one-fourth of a Roman as, making its English translation as farthing (one-fourth of a penny) almost unavoidable. Unfortunately, in the English coinage system there were no denominations smaller than a farthing, creating the problem of how to deal with Mark’s lepta/minuta.” With no British parallel for any coin smaller than a farthing, there is a good chance that the arithmetic term mite was brought into play.

Hoover also speculates, however, that Tyndale’s earlier translation might have been a little influenced by the contemporary Flemish monetary system. He continues:

After all, Tyndale is known to have had good Flemish connections, and he composed and printed his translation of the New Testament while in the nearby German cities of Hamburg, Cologne, and Worms. In 1534, Antwerp became his home and a base for shipping his contraband translations into Tudor England, until he was finally arrested and executed for heresy in 1536. Thus, Tyndale is likely to have been conversant with the Flemish currency system, in which there were twenty-four mites to the penning.

Whatever the case, British money was organized according the £sd or pound-shilling-pence system. There were 20 shillings in a pound and 12 pence (pennies) to the shilling, so a pound was 240 pence. There were smaller denominations than the penny, such as the farthing, which was one-quarter of a penny. There was an even smaller coin, worth a half-farthing (1/8 penny), that, borrowing the Flemish term, came to be known as a mite. It was for this reason that the smallest coin in circulation in early first century Jerusalem became known worldwide and probably for all time as the mite.

It is only natural that people who are interested in the stories of the Bible would want to know more about these coins and exactly which ones could be associated with the stories. In his History of Jewish Coinage and of Money in the Old and New Testament, Frederick Madden uncritically stated that the mite “was the smallest coin current in Palestine in the time of our Lord.” In a Handy Guide to Jewish Coins (1914), Edgar Rogers wrote of the story that it was natural to assume that the coins cast into the treasury were strictly Jewish and suggests that “with some degree of certainty it may be said that the popular coins for this purpose were the small copper of Alexander Jannaeus and his successors.” Whatever its origin and identity, the poor widow’s mite has become one of the most frequently referenced and most popular ancient biblical coins.

Here are two things we know about the widow’s mite story, as related by both Mark and Luke:

- It is certainly a story about charity and goodwill, rather than a story about money. The poor woman gave all she had to the treasury of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem, while, relatively speaking, many rich people gave little of themselves.

- The amount of money the widow threw into the Temple treasury was two coins of the smallest size in existence in Jerusalem at that time. There is no doubt that the small prutah (Guide to Biblical Coins Nos. 1152, 1153) or half-prutah (GBC Nos. 1134, 1138, 1147, 1185-87) coins of the Maccabean kings and Herod the Great, fit that description. The most common, easily by a factor of more than 1000 to 1, is the small prutah. It would have most likely been struck by the Hasmonean successors of King Alexander Jannaeus (103 – 76 BC), which have been documented to range in weight from 0.20 to 1.70 grams, with an average of 0.81 grams.

The massive issue of these tiny bronze coins in this poor land filled a market need. Some versions of these coins may have been first struck very late in Jannaeus’ reign and likely continued to be minted periodically until as last as 50-45 BC. These coins were all decorated on one side with an anchor and on the other side a crude star.

ANS, 1944.100.62695

Herod the Great also minted very similar looking but much more scarce coins, possibly quite early in his reign, which technically began on the ground in Judea around 37 BC. These coins range in weight from 0.49 grams to 1.78 grams with an average of 0.94 grams. Herod’s coins are decorated on one side with an anchor and on the other side with crude inscription.

The similarities of the Herodian to the Hasmonean in both design and general appearance coins suggest that the latter were crudely copied from the earlier ones, and archaeological finds suggest that their circulation overlapped. The illustration below shows the similarities between Hasmonean small prutot (GBC 1153, top 2 rows) and the slightly later Herodian small prutot (GBC 1173 – 1177 bottom 2 rows).

Both the Hasmoneans and Herod I also issued relatively small numbers of a few coin types which were clearly meant to be half denomination prutot. The best current evidence suggests that during the first century, the Judean shekel was made up of 256 prutot. Consider that there are 100 cents to the dollar and this was very small change indeed.

Archaeological evidence proves that even though these small coins were struck in the first century BC, prutot continued to circulate well into the first century AD when Jesus lived, and even as long as the fourth century AD. At the joint Sepphoris excavation in 1985, we found the small prutot of Jannaeus in the same areas as fourth-century Roman bronze coins. They were useful pieces of small change at a time and place that small change was not easy to find. Many late Roman and Byzantine small bronze coins were chopped in halves and quarters to accommodate the needs of the market.

One final aspect of the story of the poor widow’s mite remains relevant today. Many people of great means contribute little to charitable causes, while less wealthy individuals contribute a great deal relative to their ability. This is a topic fit for everyone to ponder.