Financing Sulla’s Reconquest of Italy (Pt. I)

This post (in two parts) has the ambitious goal to showcase the importance of RRDP in providing new data to the question of the financing of Sulla’s army in the crucial years between 83 and 82 BCE when, after the end of the First Mithridatic War, he marched through Italy and successfully defeated his adversaries (Appian, Bellum Civile 1.84–86). This very same topic has been recently addressed in a talk sponsored by the Department of Classics and the Interdisciplinary Program in Archaeology at the University of Virginia.

Appian states that Sulla had at his disposal an army of 40,000 men, including five legions of Roman infantry, 6,000 knights, plus Greek and Macedonian auxilia (Appian, Bellum Civile 1.79). According to M. Speidel’ s calculations (pp. 350–51, Tables 1–2), this would imply that Sulla needed to have at his disposal the equivalent of almost 10 million denarii. Since Sulla was barred from taking advantage of the enhanced monetary production of the Roman mint, it becomes clear that he must have taken advantage of the bullion supplied by his recent victories in the East.

The monetary production of the collegium of triumviri monetales of 83–82 BCE, composed by P. Crepusius (RRC 361/1a,b,c), C. Mamilius Limetanus (RRC 362/1) and L. Marcius Censorinus (RRC 363/1a,b,c,d) have been the object of foundational die studies that provided a model for future ones. Back in 1976, T. Buttrey published a fundamental study of Crepusius’ issues. Schaefer’s archive provided the material for the study of the issues of L. Marcius Censorinus and C.Mamilius Limetanus. The importance of these issues does not only reside in the historical moment they produced in, but also in their technical peculiarities. Issues like the ones produced by this collegium are defined by Richard Schaefer as ODEC: One Die for Each Control Mark. As the name suggests, ODEC issues have a specific correspondence between dies and control marks. Usually, there is a univocal correspondence between obverse and reverse dies for each of these control marks. This kind of issue seems to be more common in times of unrest, as in the years addressed here.

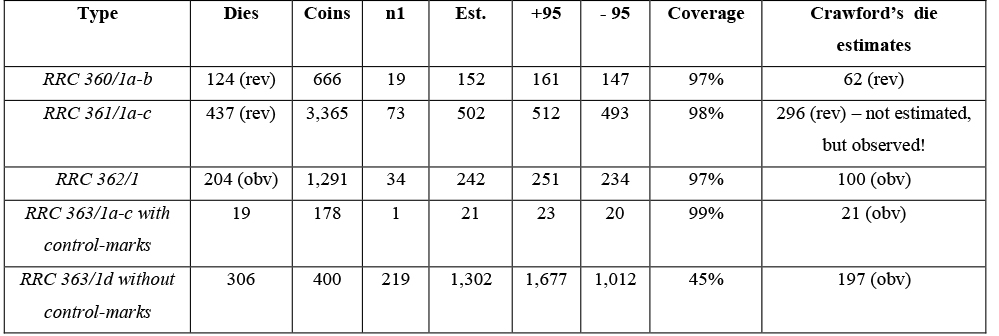

Table 1 presents the most updated estimates for the production of these moneyers.

The total of estimated dies for this collegium is 2,219, with a production that could be estimated as comprised between 32 and 45 million denarii. This is a truly exceptional production, as can be seen from Table 2.

This exceptional production, clearly dictated by the advance of Sulla’s army, will provide a necessary comparandum for Sulla’s production.

The estimates of Sulla’s production here presented integrate the data collected by R. Schaefer for three Sullan issues, RRC 359/2, RRC 367/1,3 and 5 and RRC 375/2 to revisit the scale of these issues also in light of what we know from other studies about Sullan issues at Athens and cistophoric production in Asia.

This allows us to see historical production beyond a single mint and begin to understand better the scale of the striking necessary to fund Sulla’s march on Rome.

After the battle of Chaeronea in 86 BCE, Sulla found himself master of the East. Plutarch provides a vivid description of the way in which he celebrated this victory over Mithridates. Sulla erected two trophies in the territory of the city of Chaeronea, where the troops of Mithridates’ general Archelaus first gave way, whose archaeological remains have been the object of contrasting interpretations. The two trophies probably refer to the battles of Orchomenus and Chaeronea, which resulted in game-changing losses for Mithridates. These trophies were inscribed with the names of “Ares, Nike, and Aphrodite.” These trophies were inscribed with the names of “Ares, Nike, and Aphrodite.” The reasons for dedicating the trophies to Ares-Mars and Nike-Victory seem quite straightforward, as the former was the patron of warfare and the latter was the personification of Victory herself, but the presence of Aphrodite needs some further clarification. F. Santangelo (pp. 188–90) convincingly correlates the goddess of Love on the trophies with the epithet that Sulla used in his correspondence with the Greeks, ’Επαφρόδιτος, ‘a favorite of Venus’, to stress his strong connection to the goddess. Indeed, Plutarch explicitly states that the dedication to Aphrodite on the trophies referred to Sulla’s epithet. Not surprisingly, the types of Venus and the two trophies erected after the battle of Chaeronea are also present on the aurei and the denarii issued by Sulla on his way back to Italy, very likely in 84/83 BCE.

In F. Santangelo’s words, these issues “look like a perfect epitome of Sulla’s ideological agenda,” as they have a head of Venus and the name of Sulla on the obverse and on the reverse the legend IMPER(ATOR) ITERV(M), accompanied by a jug and a lituus, two symbols that are related to the augurate and to the concept of imperium, and surrounded by two trophies, quite certainly to be recognized as the ones from Chaeronea and Orchomenus (Assenmaker 2014, pp. 216–28). We also know from Cassius Dio (18.42) that these two trophies were also used by Sulla on his personal signet ring.

As already mentioned, the same trophies are to be found on the reverse of the New Style Athenian tetradrachms presumably issued in the years 86–84 BCE (Thompson 1961 no. 1341–1345, Fig.10). The presence of the distinctive Sullan trophies on the reverses both of the New Style Athenian tetradrachms and of the aurei and denarii of series RRC 359 has long led scholars, and M. Crawford in particular, to hypothesize that the latter issues ‘were made with metal from the Greek world, presumably in large measure melted down booty’ (p. 124). In the same direction goes the orientation of the dies for this issue, uniquely adjusted at 12:00, an orientation very common in Greek coinage, but in sharp contrast with Roman Republican practices. While no certainty is possible, these coinages might have been struck at the time of the end of Sulla’s sojourn in the East (and then sent to Italy with the army) or—more likely—in Italy, right after Sulla’s army landed in Italy, as the presence of the coins in Southern Italian hoards leads one to think.

RRC 359 issues would then have been struck at the moment of the Sulla’s arrival in Italy and their types were meant to remind everybody of Sulla’s victory over Mithridates and his privileged relationship with Venus.

These tables present here the latest estimates according to RRDP:

RRC 367, a Sullan issue composed of three denarii and two aurei, is usually dated to 83/82 BCE. The triumphator on the reverse of the coins of RRC 367 leads in the same direction as the trophies on the reverse of RRC 359, namely the depiction of Sulla as an imperator beloved by the Godswho succeeded in liberating the Roman East from one of Rome’ s arch-enemies. Notice that the triumphator holds a caduceus, not a laurel branch. The caduceus was a herald’s staff, sometimes carrying the connotations we might associate with an olive branch or a white flag, but was more generally, a symbol of peace, concord, and reconciliation (Cornwell 2017, pp. 36–41). Concordia (“harmony between the social orders”) has even been suggested as a key rhetorical component in Sulla’s own civic self-presentation (Yarrow 2021, pp. 163–65). We can read the caduceus as a statement that Sulla has brought peace and order with his return.

Here are the most updated estimates for these issues according to RRDP.

Another issue attributed to Sulla on the basis of iconographic and technical choices is the denarius RRC 375/2, which has been thoroughly studied by Alberto Campana in a very recent article (A. Campana, L’emissione con “Q” di Silla (RRC 375/1–2, 82 a.C.), Monete Antiche 118 —Luglio/Agosto 2021). A. Campana based his die study on RRDP, while further enhancing the sample.

Campana based his die study on RRDP, while further enhancing the sample.

These three Sullan issues were thus almost contemporary, very likely produced between 84 and 82 BCE. The relative chronology of these issues is still under discussion, but for the aims of this post, the relevant element is that they were all issued as a means to support Sulla’s reconquest of Italy.

The aggregate volume of these emissions is remarkable, with 976 estimated dies and a probable output of 13.39–20.69 million denarii. As a comparandum, the calculations in the previous part of this talk show that the estimated combined production for the moneyers of 82 BCE is 32–45 million denarii. The issues financing Sulla’s reconquest of Italy were thus roughly one-half of the issues of the Roman mint in the year 82 BCE.

While roughly half the size of the extraordinary issues of the Roman mint in 82 BCE, the scale of Sulla’s production is still extraordinary. This begs even more urgently the question of the provenience of the bullion used, which will be addressed in the second part of this post.