A Brief History of the Receipt

Today’s post comes from Jane Sancinito, Assistant Professor of History at the University of Massachusetts Lowell and a specialist in ancient social and economic history. Her first book, coming in 2023, is titled The Reputation of the Roman Merchant. Prof. Sancinito is a graduate of the Eric P. Newman Graduate Summer Seminar in Numismatics at the ANS.

Among the least glamorous documents in our daily lives is the humble receipt. These days, in the era of contactless payment and automatically generated emails, they are mostly redundant and apt to end up crumpled at the bottom of a bag.

Few among us still diligently file or retain receipts, and most are inclined to politely refuse them, out of an ecological consciousness of our waste, a health-conscious effort to avoid the (likely) carcinogenic thermal paper on which they are printed, or just to save ourselves the hassle of disposing of them later.

Still, receipts have a surprisingly deep and complex history. They have served the essential purpose of helping us remember our past spending, of protecting us from fraud, and of facilitating the exchange (and return) of goods and services. The modern receipt—long, thin, and heat-sensitive—is the product of a long chain of methods and ideas that can be traced all the way back to antiquity. As it turns out, practical and straightforward as they are, the history of receipts is the history of humans at work, and that can be extremely interesting.

Some of the earliest preserved writing comes in the form of receipts from Mesopotamia. Among that region’s many accomplishments and firsts come some of the earliest complex economic arrangements, and where there is complexity there must, eventually, be recordkeeping.

Proto-cuneiform tablets, like this one, record the purchase and delivery of goods from various parts of the region and cover everything from modest orders of staples to luxury goods sent from far away. The very earliest source of writing we have tracks a large order of cloth sent from Mesopotamia to what is modern Bahrain. This document provides evidence of both an early sailing venture into the Persian Gulf and of the different resources that were available in these two neighboring—but distinct—areas. From these little documents, we know something of people’s tastes, of where they went and what they needed, and of how they kept track of what they bought, imported, and exported.

Like most early receipts, cuneiform tablets were mainly created by buyers as a way to track their own expenses and predict their future needs. Mesopotamian merchants, at least five thousand years ago, felt little need to tell their customers what they had purchased, so the onus fell on the buyer to keep accurate records.

It was the Ancient Egyptians, and specifically the governing bodies of Ancient Egypt, that eventually saw the utility in providing citizens with a copy of official records. They issued tax receipts as proof of payment and expected citizens to hold onto the document, or risk being charged again. Today, governments can email or text citizens to let them know much of the same information, but their confirmation of payment stands at the end of a long tradition of recording who has paid and how much.

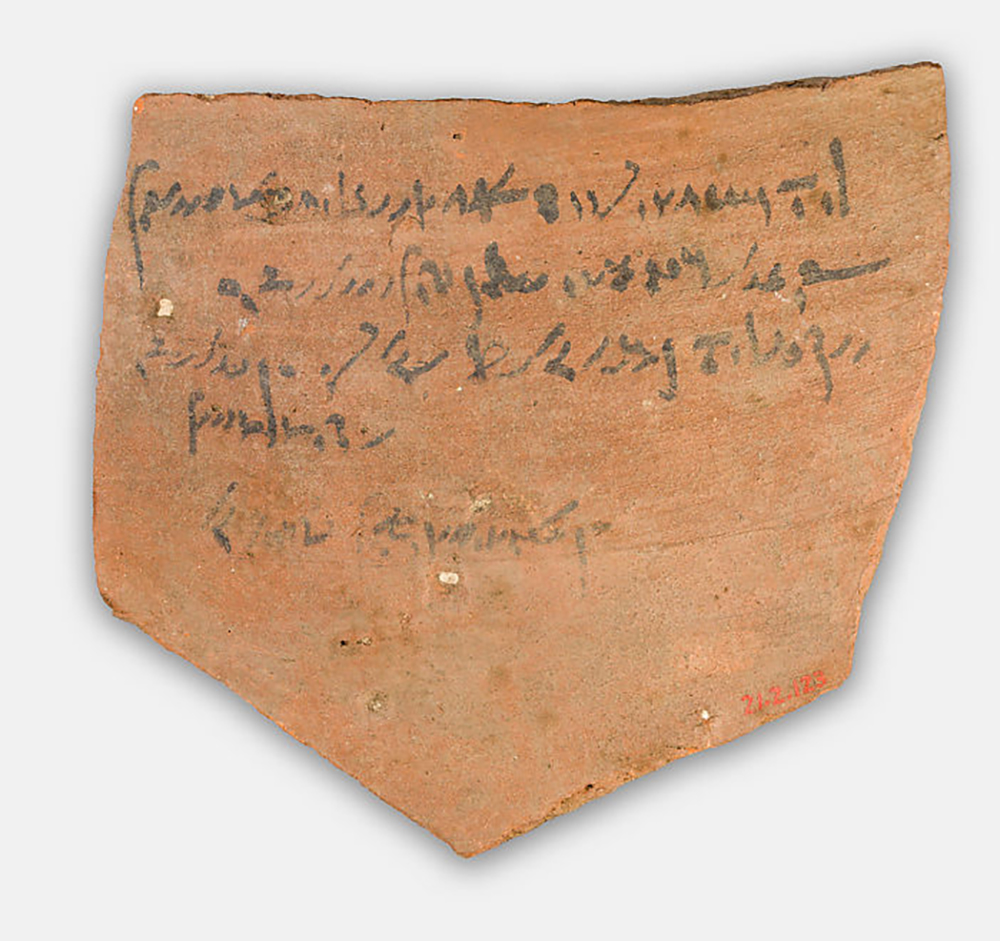

Egypt had many taxes, and their receipts came in a variety of forms. Many of them seem to us today profoundly casual, as they could be scribbled on broken pottery or on scraps of papyri. These were mostly issued for goods or animals being imported or exported and the need for receipts greatly out-stripped the supply of good papyrus. Officials collecting tolls wrote on whatever they had, even if it meant fishing a sherd out of their garbage pile.

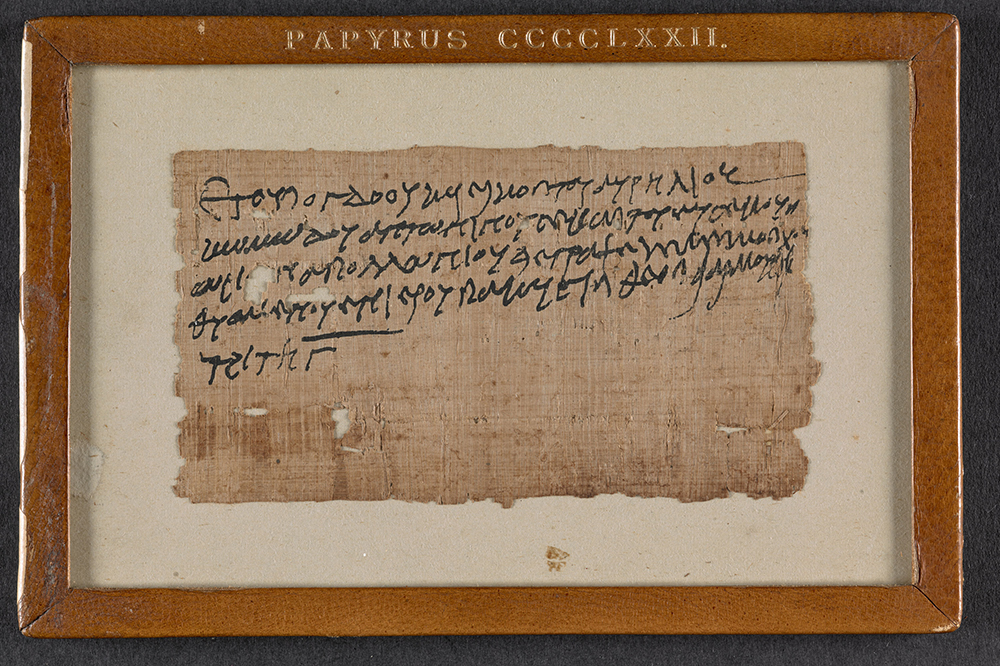

When papyrus was available, it was the preferred medium for receipts. Today, papyri, especially from Roman Egypt, are preserved in large numbers and grant historians unparalleled insight into the daily life and challenges of ancient people.

This papyrus records a tax that was levied on a calf. The text is brief, and does not specify the amount paid, but from it we know that Horion, the son of Apollonius, paid a tax on a calf that was intended for sacrifice in a temple. This receipt actually records the name of a rare, probably local, god Πακῦσις, Pakusis, whose responsibilities are now unknown. Still, from this little scrap, we know that the calf was offered to that deity over 1800 years ago.

Relatively few receipts are known from antiquity that are unrelated to taxation of one kind or another. Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans likely kept personal ledgers of what they bought in the forum or agora, as works like Xenophon’s Oeconomicus encourage householders to budget and spend with care. We know that sellers also must have kept track of their sales, especially when they sold to customers on credit or loaned out money, but few examples of this kind of accounting remain.

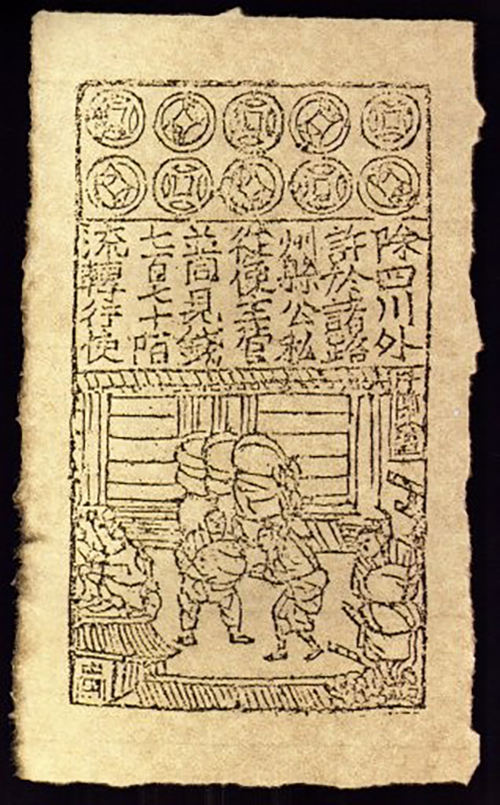

In the late Roman and medieval world, banking systems slowly grew more complicated, and receipts become more plentiful. In time, they became an invaluable piece of long-distance trade. Bankers and moneylenders were the ones who realized the potential receipts had and soon began to offer merchants and other travelers a deal: deposit your money and take a receipt; then, when you arrive at your destination, take the receipt to bankers there, and they, for a small fee, will give you “your” money back. Receipts facilitated trade across different currencies, and meant that travelers did not need to carry heavy gold or silver whenever they left home. These receipts were very valuable in their own right and they eventually morphed into promissory notes, receipts or IOUs, that, once they acquired sufficient legal backing, shared many of the same uses as paper money.

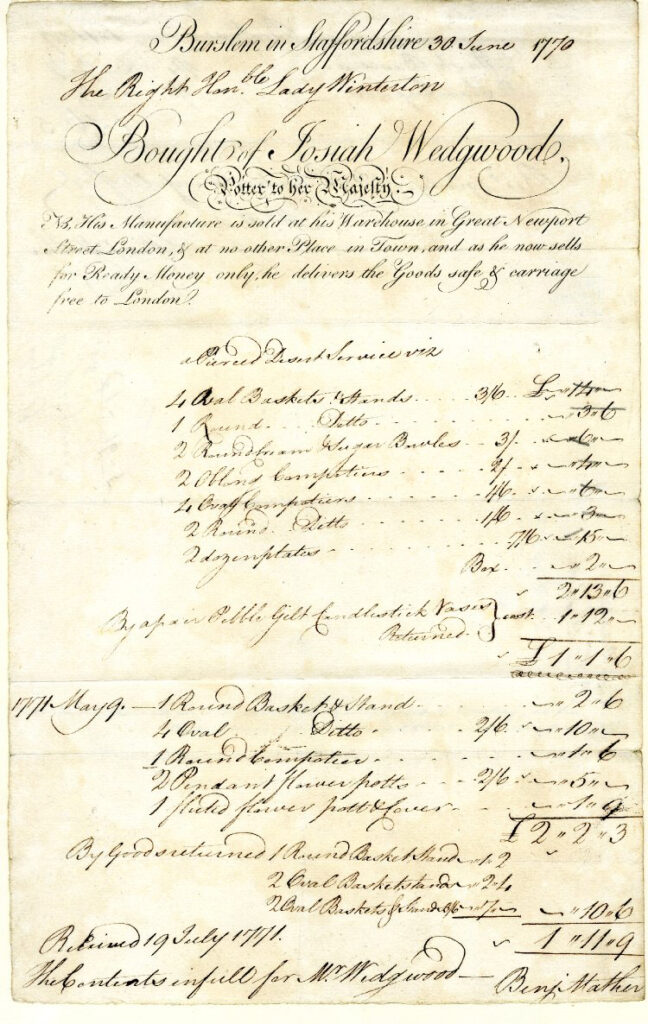

In the early modern period, receipts as we know them today—produced by the vendor for the consumer’s personal records—became both widely available and an expected practice. The advent of moveable type made it possible for merchants to order pre-printed forms that could easily be completed with the specifics of a transaction. By the 18th century, receipts could be elaborate, even highly decorated, to suit the needs of the vendor. This example not only boasts that the seller, Josiah Wedgwood, was “Potter to her Majesty,” Queen Charlotte who acted as regent for her husband George III, but also that goods could be transported to London free of charge.

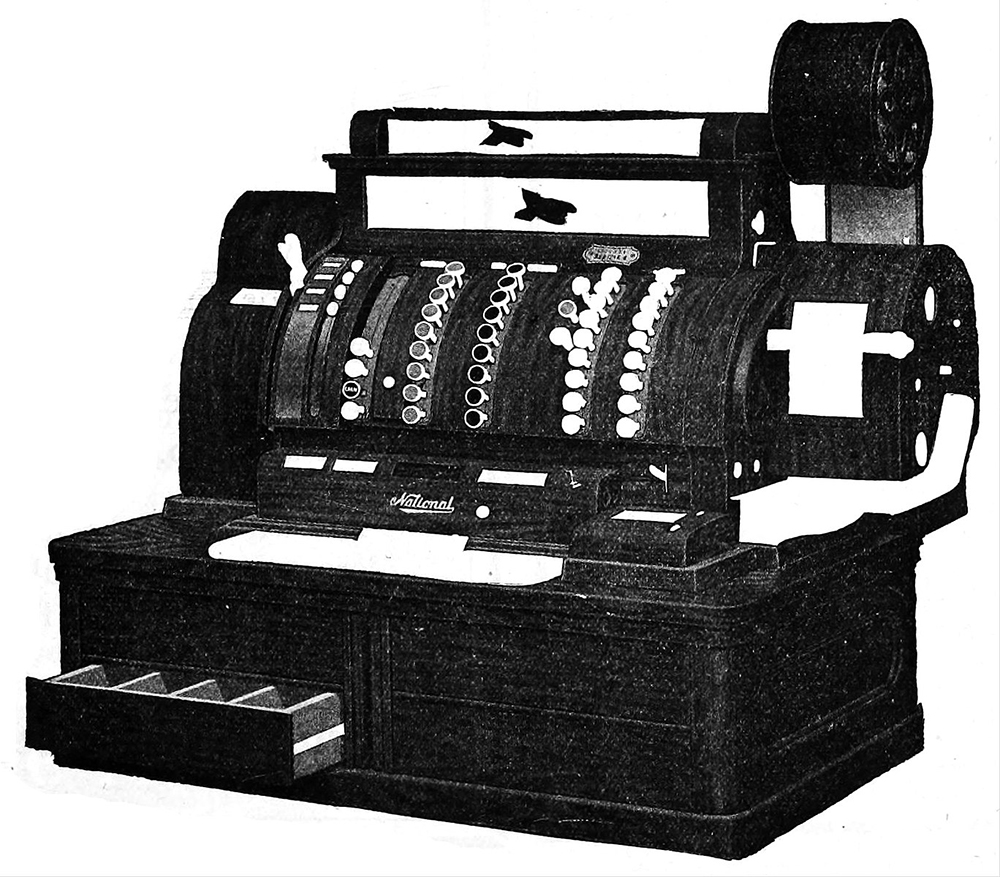

The late 19th century saw the mechanization of receipts, with the invention of the cash register by the National Cash Register Company of Dayton, Ohio. While these machines initially only tallied up sales and calculated change, they quickly adapted to generate receipts. Special paper and ink were now required to supply the machines, but these inconveniences were balanced with greater speed and accuracy of accounting for sellers and convenience for the customer.

Over the course of the 20th century, stores adapted to the use of credit cards and initially used card imprinters and carbon paper to create separate credit receipts. After the invention of electronic payment terminals in the 1980s, most registers adopted thermal paper as a way to save ink without sacrificing clarity or speed and to combine receipts that detailed the goods purchased with the receipt for the credit card purchase.

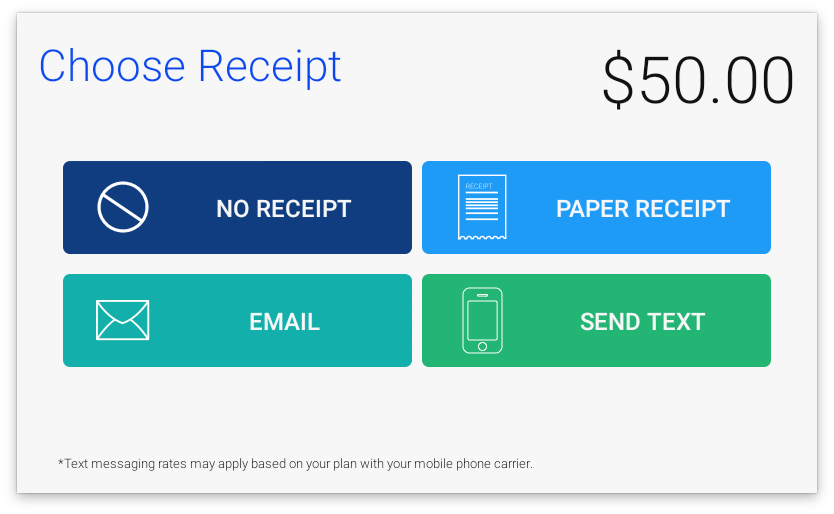

Today we have many kinds of receipts. Paper is still commonplace, available nearly everywhere, but, if we are willing to part with our personal data, we can receive a record of our purchases by email or text.

We can even refuse receipts entirely, as new point-of-service devices offer the option to save a tree and keep inboxes tidy, since cards, debit and credit alike, preserve a running ledger of our expenditures. Behind the scenes, all that data is compiled by companies and banks and leveraged, not only for our convenience, but also to gather ever-more data about our habits and tastes.

With receipts, it seems, we have simultaneously revolutionized and found ourselves at the end of a long evolution. On the one hand, digitization has facilitated a near-instantaneous exchange of information and changed the whole system in less than a generation. With the push of a button, we can have a receipt or an up-to-the-minute record of the contents of our bank accounts. Customers have more options than ever before, and their preferences are increasingly taken into account by more and more sellers. On the other hand, the form of receipt has fossilized. Though they might take any number of possible forms, most receipts these days preserve their early modern form: the vendor’s name at the top, separate columns for items and prices, culminating in a total, typically at the bottom right. Though the earliest receipts were paragraphs, the advent of double-entry bookkeeping in the Middle Ages fundamentally changed the way we think accounts should look. Thus, even as we take full advantage of technological advancement, we preserve part of the long history of receipts.

This holiday season, or as the new year rolls around, take a second to give your receipt a second look. If nothing else, it is a piece of history and someday a historian may be happy to study all the items you couldn’t live without, and how you and your society decided to record them.