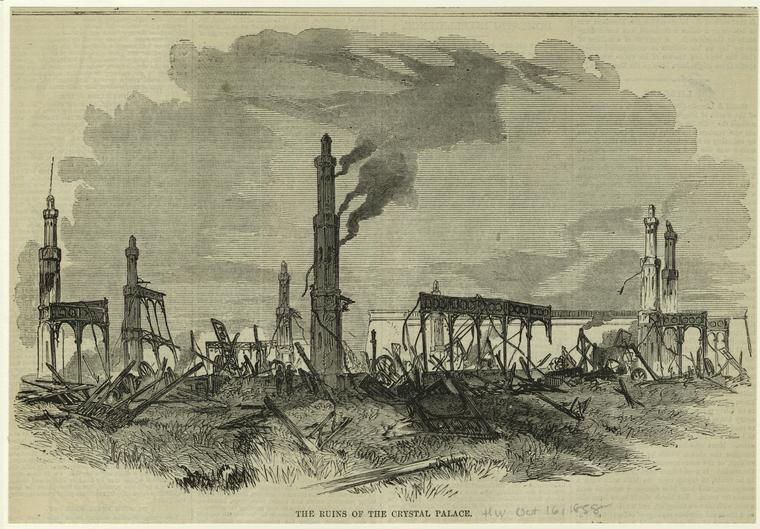

The New York Crystal Palace in Flames—October 5, 1858

On October 5, 1858, the New York Crystal Palace burned to the ground in just forty minutes after a fire broke out in the northeast corner of the building just after five o’clock in the evening. The American Institute, a civic organization dedicated to “encouraging and promoting domestic industry,” was holding its annual fair, and about two thousand visitors were in the building at the time. The New York Herald (October 6, 1858) reported that despite scenes of “indescribable confusion,” remarkably no one was killed in the fast-moving blaze.

Although the enormous structure was mostly made of iron and glass, the pitch pine that was used as flooring and in much of the framework “afforded a most inflammable pabulum for the conflagration to feed upon.” In a particularly evocative passage the Herald noted that at one point “the whole palace was like a burning coal, and vomiting up fire at a rate that would have done credit to Vesuvius.” The vivid scene was captured in a hand-colored lithograph by Currier and Ives in which you can make out a company of red-shirted New York City firemen arriving in the foreground to vainly battle the roaring blaze.

The New York version of the Crystal Palace was constructed to host an “Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations” in 1853, which was an American effort to replicate The Great Exhibition of 1851 held in London’s Hyde Park. The building was designed by architects Georg Carstensen and Charles Gildemeister in the shape of a Greek cross with arms measuring 365 feet in length and capped with a 100-foot diameter dome at its center. For the architecturally inclined a full description of the building with plates can be found here. The building was located on a site between Fifth and Sixth Avenues on 42nd Street, in what is today Bryant Park. It was completed in June 1853, at which time this large medal was struck to commemorate the occasion.

The obverse shows the Crystal Palace in all its glory while the reverse depicts a globe surrounded by allegorical figures bearing the varied attributes of industry. The beatified figure of Europe reigns supreme at the top while a man in native dress looks up at her from below. As the title and imagery implies, the exhibition was intended to highlight the industrial and artistic achievements of the United States, and the supposed march of civilization. The exhibition proved popular and it provided a model of sorts for the string of World’s Fairs that were subsequently staged around the country. Between July and November, over a million people visited the Crystal Palace to take in the exhibits and enjoy the varied entertainments that were on offer. One of the more unusual attractions on the grounds was the Latting Observatory, a 315-foot tower built adjacent to the exhibition building.

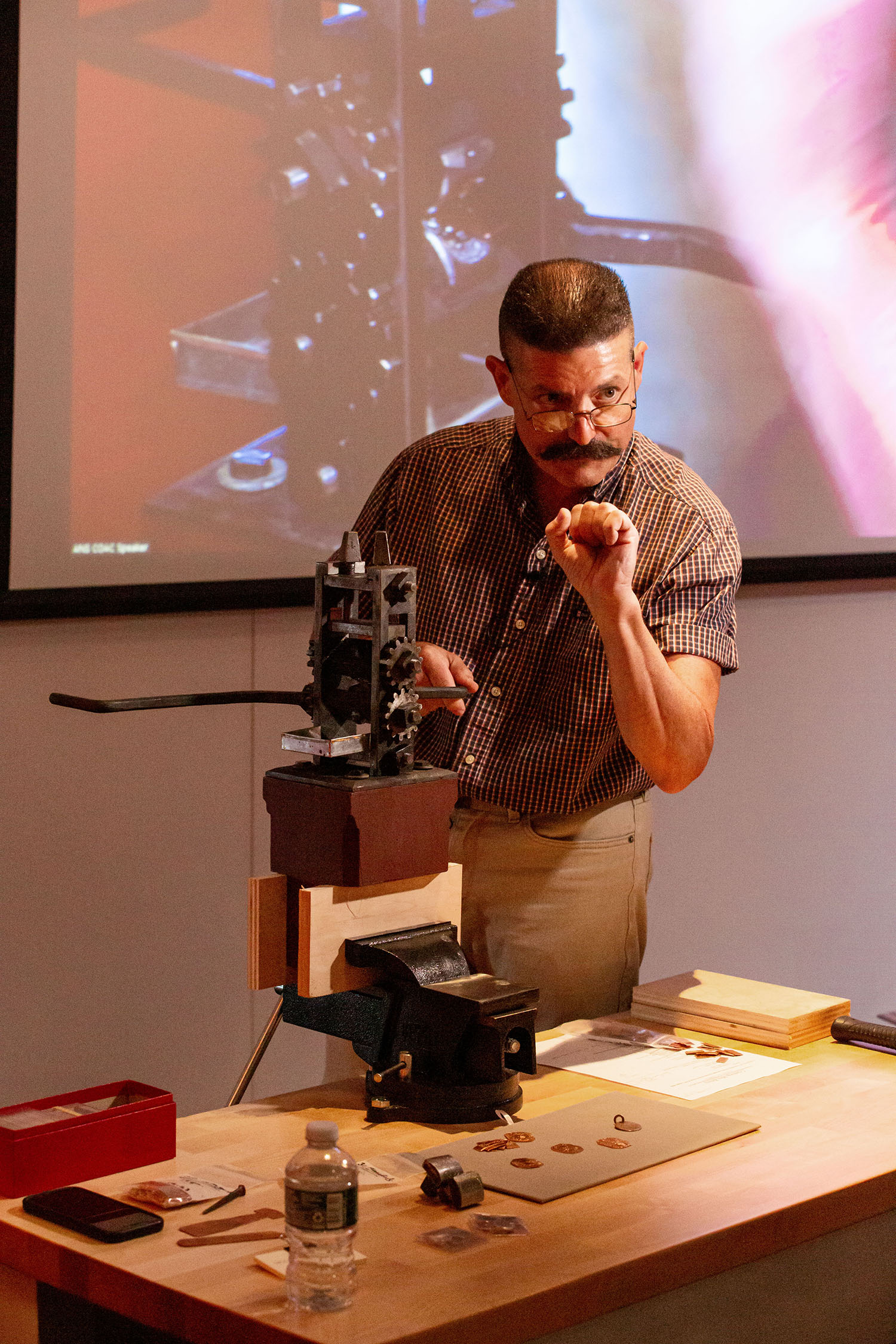

As depicted in this medal struck by G. H. Lovett, the Observatory was an iron-braced wooden structure with stores at its base and three landings from which visitors were treated to a panoramic view of the growing city. The tower did not live to see the fiery demise of its neighbor, as this structure was itself consumed by flames a few years prior to the spectacular Crystal Palace fire. It was not until the New York World Building was completed in 1890 that another structure in the city surpassed three hundred feet in height.

Despite the ostensible success of the initial exhibition, the Crystal Palace was something of an ongoing problem for the city and its owners as the building was simply too big to be of much practical use beyond the occasional event. For all of the remarkable happenings and superlatives that graced the short-lived structure, the Herald‘s description makes it clear that its dramatic and destructive final act on October 5, 1858 might have left the biggest impression.