Ground Control to . . . Abe Lincoln?!

In the most recent issue of the ANS Magazine, I wrote an article on the existence of bacterial life on the surface of coins and paper currency. The discovery of these microbial lifeforms in the second half of the nineteenth century truly helped to advance the understanding of Germ Theory. This was especially true amongst the masses, many of whom may not have otherwise had access to the experiments performed at the time if it weren’t reported in newspapers. They began to fear their money due to its circulatory nature and potential to get them sick.

On Mars, however, humans hope to find microbial lifeforms. Formed in 1993, the Mars Exploration Program is NASA’s attempt to find it. This long-term initiative has sent orbiters, landers, and rovers to the planet, with four different missions still in operation: 2001 Mars Odyssey, Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, Mars Science Laboratory, and MAVEN (as well as four completed missions, two failed missions, and one mission planned for the future). The principal component of the Mars Science Laboratory is the Curiosity rover—a car-sized, 1-ton vehicle used to explore the climate, geology, and possibilities of life in the Gale crater of Mars, whether now or in the past. Launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida, on November 26, 2011, it took 254 days to reach the Red Planet’s surface.

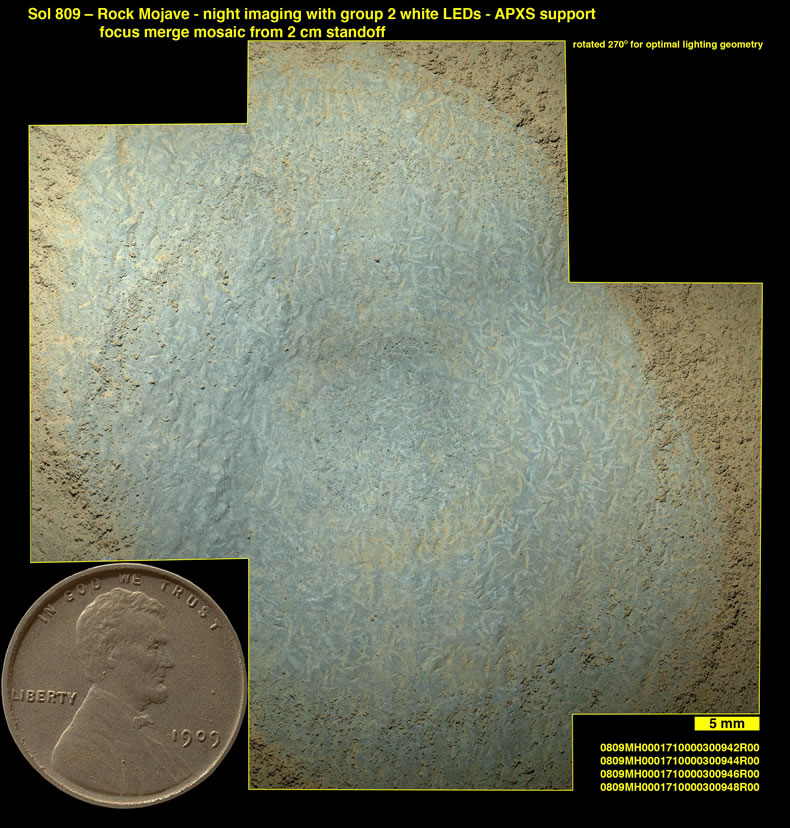

Just like with the advancement of Germ Theory in the nineteenth century, there is a coin helping to lead the way towards finding life on Mars. The primary method of analysis for Curiosity is through cameras, of which there are six different types for a total of 17. One of the 17 cameras is the Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI), which is located on the robotic arm of Curiosity. This camera, while it has long-distance focusing capabilities, is primarily used to take microscopic images of rock and soil with the hopes to find microbial evidence. It can produce images in true-color at a resolution of 1600 × 1200 pixels (now considered quite low) with the ability to focus to 14.5 micrometers per pixel.

On MAHLI, a 1909 VDB Lincoln cent is a part of its spatial calibration—a process necessary for both long-distance and up-close images (fig. 1). This provides a photographer, or MAHLI in this case, with a frame of reference to an object of known size. The Lincoln cent on board MAHLI is not essential to its calibration, which uses a more-precise ruler for the actual measurement through a series of black-and-white lines known as a scale bar. The 1909 VDB cent serves two key purposes, however. First, according to Ken Edgett (MAHLI Principal Investigator), it is a nod towards less-precise and “on the go” methods of spatial calibration used by early geologists on Earth, who often placed random coins into close-up photographs. Second, it serves as a calibration tool for the general public (fig. 2). While the scale bar gives scientists more-precise calibration details, this tool is still quite foreign to most people. The Lincoln cent, however, is one of the most ubiquitous objects on Earth. With hundreds of billions of these pennies having been produced, most individuals can instantly recognize them, know their general size, and can quickly grasp the size of another object placed next to one.

But, why a 1909 VDB cent? These coins are not necessarily rare, but there are many Lincoln cents from other dates that could have been easily acquired. According to Edgett, who considers himself an “amateur” collector, this coin was intended to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Lincoln cent, as Curiosity was originally slated to launch in 2009. This, however, was delayed, and since the window to launch to Mars comes roughly once every 23 months, the mission had to wait until 2011. “When the launch was delayed,” Edgett said, I made a decision to stick with the historic 1909 cent rather than try to find a 1911 cent. Honestly, I think 1911 would have been more difficult to explain.” I concur. While I was initially unaware exactly why Edgett opted for the 1909 VDB cent, that date just made sense, whereas a 1911-dated cent would have required some investigation to correlate it with the date of the launch. Furthermore, a 2009- or 2011-dated coin could not have worked because of the zinc inner core that became standard for Lincoln cents midway through 1982. Zinc is known to sublimate in a vacuum environment (especially at higher temperatures) and cause short circuits. Regardless of the date chosen, and knowing that money from Earth is covered in bacteria, NASA made sure to sterilize this specimen before takeoff to ensure not to introduce Earthly microorganisms to Mars.

The specimen that is currently (and probably forever will be) on the surface of Mars was one of four that Edgett purchased specifically for NASA. Two other 1909 VDB cents were used in testing the calibration panels at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, and the fourth was kept for possible use in future missions. Initially intended to be a two-year mission, the Mars Science Laboratory has been extended indefinitely, and Curiosity has been roaming Mars for eight-and-a-half years with the coin bearing the likeness of Abraham Lincoln keeping its images sharp (fig. 3).