Mahlon Day's Originary Counterfeit Detecter, 1828

One of the most overlooked aspects of both numismatic and printing history in the United States is the ephemeral genre of serials known as “counterfeit detectors.” These publications flourished in the antebellum era, when a chronic lack of coinage led individual banks and businesses to issue diverse forms of paper money. A trickle of notes issued by private banks in the late eighteenth century turned into a veritable flood by the 1820s as an ever-greater number of banks issued increasingly large amounts to satisfy the needs of the growing populace and economy. These privately issued bank notes were a kind of representative money that promised the holder that the paper could be redeemed at the bank for specie, i.e. gold and silver, on demand. In practice this was not always the case as a given bank’s ability to ‘make good’ its circulating notes was often questionable.

While this newfound capital helped to fuel the United States’ runaway growth, the sheer number of different designs and varying quality of the notes created a chaotic currency situation that was ripe for abuse. Perhaps the biggest problem was the integrity of the note-issuing banks themselves, which ranged from prudent and well-capitalized institutions to unsafe and even outrightly fraudulent ones that printed notes with no intention of ever redeeming them. Rampant counterfeiting only further confounded matters, and the public was put in the essentially impossible position of attempting to assess whether or not a given note was genuine, and even if so, what it exactly it was worth for an incredible range of currencies.

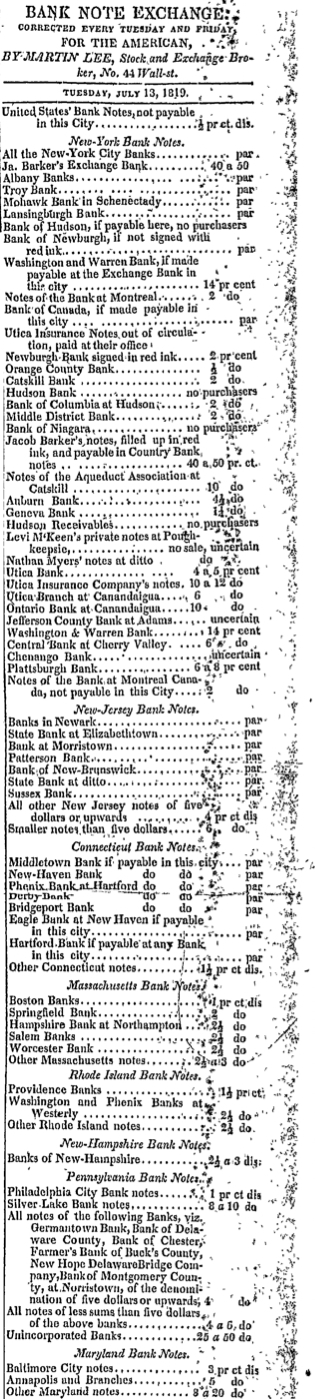

In an attempt to bring some clarity to this confusing situation, publishers printed broadsides and circulars that listed commonly counterfeited notes. Newspapers, most notably the Baltimore-based Niles Register (1811-1836), also featured financial columns that advised readers about the soundness of various banks, reported exchange rates, and took note of counterfeiting activities around the country. Yet it was not until 1819 that The American, a New York City newspaper, began to regularly publish a table entitled “Bank Note Exchange,” which gave the going rates for assorted notes and listed known counterfeits. The table at left is reproduced from the July 14 edition and indicates that it was updated every Tuesday and Friday by Martin Lee, a broker with offices at 44 Wall Street. A rating of “par” indicated that the note was equal to its printed value, while a number followed by “do” indicated the rate at which the note was discounted, which typically was related to either the perceived soundness of the issuing bank or its distance from the city. The column shows that notes issued by banks in Baltimore, for example, were discounted 3 percent, making a ten-dollar Baltimore bank note worth $9.70 in New York. Banks further afield suffered from even steeper discounts, and the geographic disparities created opportunities for “bill brokers” and “note shavers” to acquire and transfer the notes around the country at a profit. By the early 1820s, bank note tables became increasingly common in American newspapers, and often included notices about known counterfeit and so-called “spurious” notes that were issued by fraudulent banks. These bank note tables and columns were the precursor to a genre of newspapers that emerged in the late 1820s that focused almost entirely on the legitimacy and value of paper money in circulation.

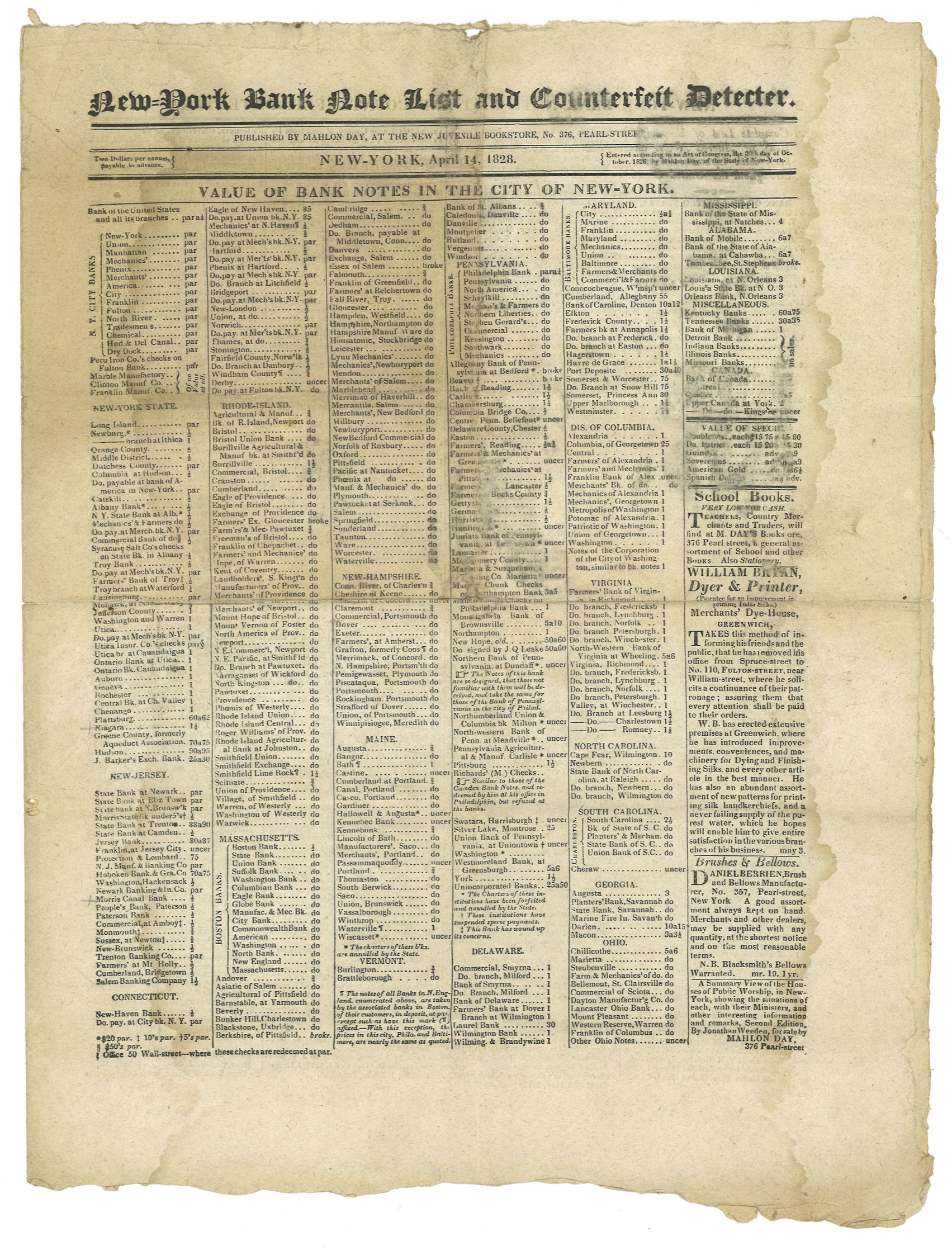

William H. Dillistin’s Bank Note Reporters and Counterfeit Detectors, 1826-1866 (1949) represents the only serious study of these popular publications to date. As delineated by Dillistin, these serials had two essential purposes: (1) “to show the rate of discount at which uncurrent notes would be purchased or exchanged for specie in the more important business centers,” and (2) “to furnish a brief description of counterfeit, spurious, altered, and raised notes.” The noted New York printer and Quaker Mahlon Day (1790-1854) was the first to publish a bank note list and record of counterfeits at regular intervals, beginning a biweekly broadsheet in 1826 called the New York Bank-Note List and Counterfeit Detecter. Because each new issue superseded prior editions with updated information, they were typically discarded and few examples have survived relative to the numbers in which they were printed. A survey of major libraries for Day’s New York Bank-Note List and Counterfeit Detecter, which was published continuously from 1826 to 1851, turns up only a few dozen extant issues. When Dillistin produced his 1949 study, the earliest that he discovered was an August 1830 edition at the Huntington Library. Looking through a sheaf of counterfeit detectors donated to the ANS the other day, I discovered an even earlier date.

The April 14, 1828 edition of the New York Bank-Note List and Counterfeit Detecter is a four-page folio approximately 20 by 13 inches in size. Underneath the title, an inscription reads: “Published by Mahlon Day, at the New Juvenile Bookstore, No. 376, Pearl Street.” Indeed, Day is perhaps better known today for his pioneering role in publishing children’s books, but combating counterfeiting also proved to be a profitable business. A notice lists the price of a subscription to the paper as two dollars per annum, and indicates that the serial was “entered according to an Act of Congress the 30th day of October, 1826,” which raises the possibility that there might be even earlier extant issues that could come to light.

The first page lists the value of notes for over one hundred banks around the country in the city of New York at that time, indicating whether particular notes were circulating on par with their nominal value or at a discount. Bankrupt banks were straightforwardly labeled as “broke,” while in many cases the value of given bank’s notes were listed as “uncer,” i.e. uncertain.

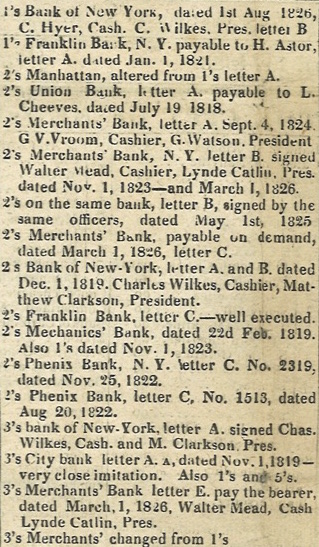

The remaining three pages of the paper were taken up with what purports to be “A Complete List of Counterfeit Bills, of Altered Notes, and those with Spurious Signers, throughout the United States,” organized by geography and denomination. The list offers a window into the principal means by which counterfeiters operated. The most straightforward method was to simply reproduce a genuine note as best as possible. The Counterfeit Detecter sometimes described a bogus bill in detail, explaining for example that a twenty-dollar note attributed to the Charleston Branch of the Bank of the United States was “fainter than the genuine, particularly the eagle and work around it,” and that it was “shorter than the genuine note.” Other known counterfeits were simply listed, as in this excerpt from the section on New York City banks. Here one sees a listing for a counterfeit $2 note from the Merchant’s Bank dated March 1, 1826, The ANS actually holds an example of this particular note, which although crudely made, we did not regard as a counterfeit until reading this counterfeit detecter.

Day’s Detecter also shows that wholesale counterfeits were less common than the practice of “raising” bank notes, which involved changing the denomination of a genuine bill. The New York City excerpt above indicated $1 notes of the Manhattan Bank were being altered into $2 notes and that $1 notes of the Merchant’s Bank were being changed into $3 notes. In the specimen below, a genuine one-dollar note issued by the Northern Bank of New York has been raised to a value of ten dollars, the telltale signs being the discoloration around the engraved numbers, which were rubbed or cut out and then replaced with the higher value.

Note the dark spots around where the numbers have been altered. While this counterfeit was not particularly well crafted, I chose it as an example because the tampering was so easy to see. Better executed raised notes were very difficult to detect without the kind of specialized information that counterfeit detectors provided. Another technique for altering notes was to change the name on worthless paper issued by a broken bank to that of a sound institution. Day’s Counterfeit Detecter thus also lists “spurious” notes, which refers to either currency issued by plausibly-named but non-existent banks or those notes that were purely fraudulent, bearing no resemblance to any genuine notes. That notes for a completely fictional bank could and indeed did circulate suggests something of the confusion that reigned in the monetary system and the appeal of something like this serial that helped individuals and businesses navigate the bewildering mix of paper money in circulation.

The two-and-a-half pages devoted to counterfeits list over eight hundred fraudulent notes, which casts some light on the scope of the problem; and it was one that was only getting worse as banks and bank notes proliferated amidst the Market Revolution. A short notice “To our Patrons and Friends” on the back page of Day’s paper informed readers that the publication would soon be increasing in size and promised “an improved general appearance,” and asked “the community for a continuance of their favors.” By 1830, it was an eight-page publication and in 1837 Day’s Counterfeit Detecter expanded to sixteen pages. Clearly Mahlon Day had struck upon a popular and profitable idea, and it would not be long before competition in counterfeit detection began to heat up. Interestingly enough, the back page of the paper contains and advertisement for Sylvester J. Sylvester, a broker who would shortly become Day’s biggest rival and whose endeavors we will cover in part II of this series.