ISIS, Numismatics, and Conflict Antiquities

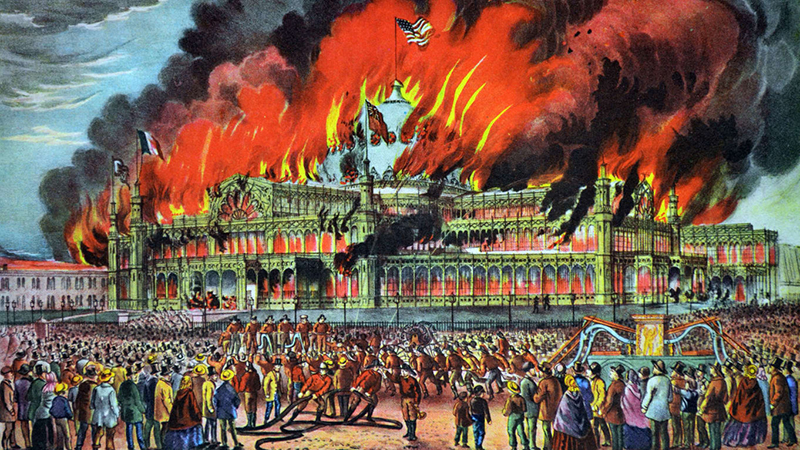

In preparing a session on cultural property issues for the Eric P. Newman Graduate Seminar, I was reading more of the news about the systematical looting of Syria. The debate about how the sale of antiquities, including coins, helps to fund ISIS has been hotly contested, but images such as the aerial views of the ancient site of Dura-Europos are just too depressing for words.

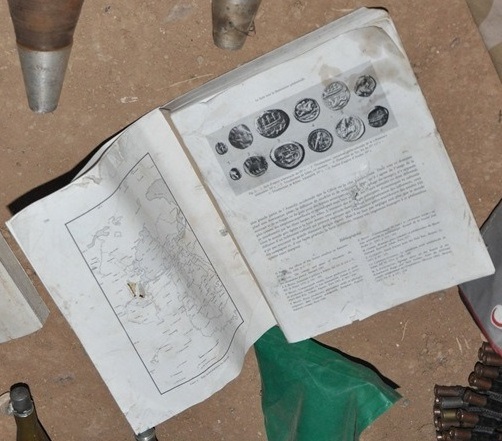

What I had missed until I read Sam Hardy’s blog on conflict antiquities is the discovery of a numismatic book among an unlikely assortment of weapons and somehow academic-looking publications. The photograph below was one taken of materials confiscated by the Kurdish People’s Defence Unit after a battle with Turkish Islamic State fighters.

(c) Mehmet Nuri Ekinci, Ajansa Nûçeyan a Firatê (ANF), 3rd June 2015

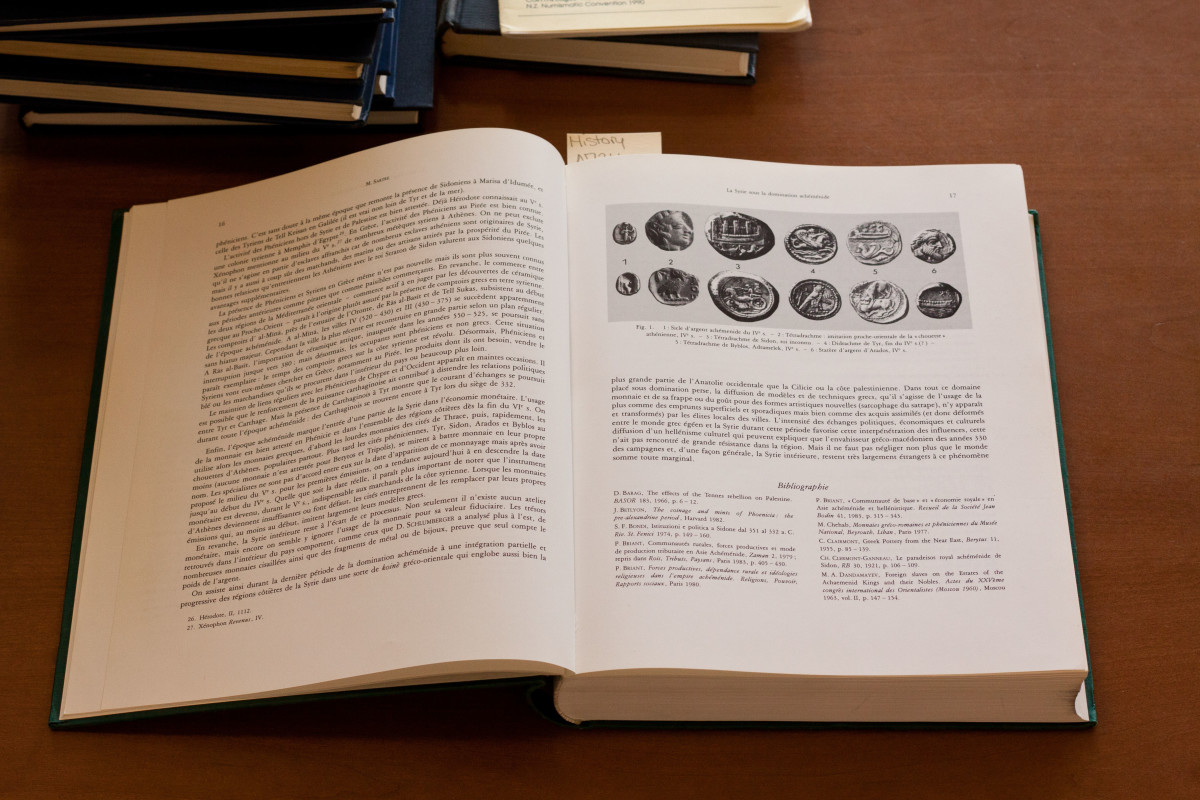

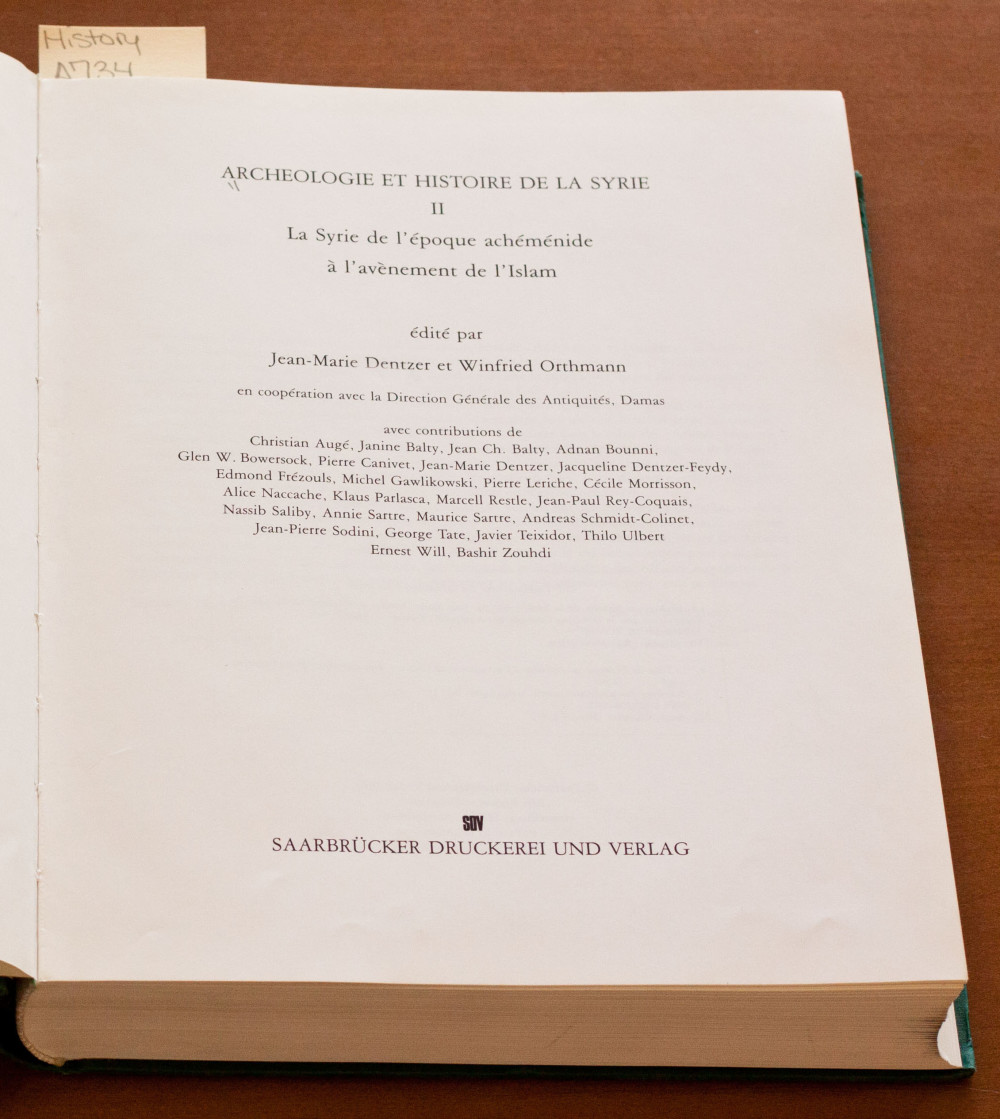

An open page shows what numismatists and archaeologists identified immediately as a group of various Persian and Phoenician coins, with some text below. I knew right away that I had seen this page some time in the past, and after a few minutes I was able to decipher the title of the article, ”La Syrie sous la domination achéménide” by Maurice Sartre. A Google search quickly confirmed that this was published in the volume Archéologie et Histoire de la Syrie II, edited by Winfried Orthmann and Jean-Marie Dentzer and published in 1989. Here is the entry for the book in the ANS Library Catalogue, and upon arriving at the ANS this morning, I was able to confirm the identification:

Towards the end of the book, there is a map of archaeological sites of Hawran, an area in southwestern Syria:

The confiscated book is missing the first pages, its dark-green hard cover, and very last page (p. 591). The page with the text and images of coins in the Syrian photograph is page 17. Incidentally, the first volume of Archéologie et Histoire de la Syrie was published in 2013.

There is indeed a personal connection of mine to the book. Winfried Orthmann was professor of Near Eastern Archaeology at Saarbrücken University, where I attended his lectures as an undergraduate. And the book was published and printed in my hometown Saarbrücken.

Now how this very scholarly book on archaeology of Syria ends up in the hands of ISIS fighters is an interesting question. I, for one, have never underestimated the often erudite knowledge people who are involved in looting ancient sites in the Mediterranean. For people interested in a general overview of coins from Syria, this book is indeed helpful. Articles by Christian Augé on “La monnaie en Syrie à l’époque hellénistique et romaine” (pp. 149–190, with four plates illustrating 71 coins) and by Cécile Morrisson (who won the ANS Huntington Medal in 1995) on “La monnaie en Syrie byzantine” provide excellent and well-illustrated introductions to the coins of this region. Her article gives a considerable amount of detailed scholarly information on site finds of coins in Syria.

So this is an extremely unlikely find—a scholarly, not exactly inexpensive, and heavy—book on the archaeology of Syria in the hands of ISIS fighters. If anyone doubts the multifaceted connections between looted antiquities and war in Syria, this discovery has to make one wonder.

Update:

After my last post identifying the Archéologie et Histoire de la Syrie (1989) as the volume confiscated from ISIS fighters, Professor Winfried Orthmann, one of the editors of this German collection of essays on the archaeology of Syria, sent me an email. He informed me that he had sent a copy of the book to the director of antiquities at the Ar-Raqqah Museum. It is also possible that the had an additional copy of the book. Raqqa, a city in the Euphrates River in the northern region of Syria, has been a stronghold of ISIS for a while, and the looting of its museum has been widely online (see, for example, this and this). In any event, it is certainly possible that this relatively rare academic volume seen in the photos was one of the copies from the Ar-Raqqah Museum.