St. Helena, the First Christian Pilgrim

On a visit to Rome, we sought out the church of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme. My American Express Guide to Rome (long out of print, but still handy) says it was “One of the seven pilgrim churches of Rome, it is said to have been built to house the precious relics of the True Cross brought to Rome from Jerusalem by St. Helena, the mother of Constantine.”

It is said that Helena founded the church on land where her private palace stood. Although it was on the edgte of the city, the relics of the crucifixion of Jesus Christ that Helena brought back from Jerusalem made Santa Croce in Gerusalemme a center for pilgrimage. Most important were some pieces of Christ’s Cross (croce means “cross”) and part of Pontius Pilate’s inscription, called the Titulus Crucis, proclaiming “Jesus of Nazareth King of the Jews,” written in Latin, Hebrew, and Greek. There is little doubt that this wooden plaque is very old, but numerous tests performed over the years have never established its authenticity absolutely. Nevertheless, even to a non-Christian observer, it is quite moving to view these relics.

When we entered the church, only a few days after Easter, we seemed to be the only visitors. We walked up to the altar and around the chapel. We did not see any relics, so we made our way into the smaller side rooms and found them in a small room behind the main altar. Here we saw St. Helena’s relics: three pieces of wood set in a larger cross; they are said to be actual pieces of the True Cross. Two thorns, said to be from Jesus’ crown of thorns are mounted and stand alongside it, as does a piece of a bronze nail, said to be from the crucifixion itself. And finally, we saw the piece of wood that is said to be from the sign Pontius Pilate was said to have erected over Jesus while he was crucified.

Whether or not they are authentic relics, I cannot say. But seeing them was a fascinating experience.

It led me to recall the importance of Helena, later revered as St. Helena, to the ancient land of Israel. Hers is a real “rags to riches” story. We believe Helena was born in about 249 AD in the town of Drepanum in Bythnia, which Constantine later renamed Helenopolis. St. Ambrose referred to her as an inn-keeper, others say she was a simple bar maid in her father’s tavern. Eventually she attracted the attention of a Roman soldier, Constantius Chlorus and she became either his longtime mistress, or his wife. In either case there is no doubt that together they bore a son, Constantine.

In 292, when Constantius became Caesar of Spain, Gaul, and Britain, he dumped Helena and married Theodora, the daughter of Maximian, his patron.

Meanwhile, Helena’s son Constantine became a soldier, and spent a lot of time at Diocletian’s court. When Constantine persuaded the Roman legions in Britain to proclaim him Caesar in 306, he immediately called for his mother and installed her in his court with the appropriate honors befitting the mother of the Emperor.

In 312, the most significant event of Constantine’s reign occurred. While preparing for a battle with the army of his rival Maxentius at the Milvian Bridge in Rome, he saw a cross in the sky with the inscription IN HOC SIGNO VINCES (“In this sign you will conquer”). He immediately ordered his troops to paint the monogram of Jesus, the labarum, on their shields and this extra strength enabled their victory and gave Constantine control of the West as well as the East, whereupon Constantine vowed to make the Roman Empire a Christian nation.

In 324 AD Constantine named Helena as “Augusta,” a title that was established by Augustus for Livia, but certainly not granted every empress, much less every royal mother.

In 325 AD, the Council of Nicea met and Constantine declared Christianity to be the nation’s official religion. Incidentally, it is not clear whether Constantine himself actually ever became a Christian. His mother, Helena, was not only converted but was so excited by her spiritual experience that it enticed her to make a pilgrimage, circa 326 AD to Judea, where she could visit all of the sites that were important in the life of Jesus. She was in her late 70s at the time she embarked. Helena’s pilgrimage was the prototype for the travels of virtually every Christian pilgrim to the Holy Land for some 1,700 years, right up to today.

Until Helena’s visit, nobody outside of the Christians in the Holy Land had paid much attention to the sites there. In Helena’s day the Jews maintained important academies at Tiberius, Sepphoris, and Lydda (Lod). Led by Rabbi Yehudah Ha’Nassi the Jewish scholars were in the final stages of developing the Talmud itself. When I was the numismatist at the Joint Sepphoris Expedition in 1985 and 1986, led by Duke’s Eric and Carol Meyers and Hebrew University’s Ehud Netzer, we discovered some remarkable mosaic floors—and many more were subsequently discovered at Sepphoris—which indicated that the city was extremely wealthy at the time Helena arrived in the country. In fact, we dated some of these mosaics by small groups of Constantinian coins lying on top of and just under them.

While there is no doubt that the local traditions held some, or perhaps many of the sites Helena visited as holy shrines, it did not hurt that the mother of the Emperor of Christian Rome further declared the sites to be true.

And indeed, Helena was said to have:

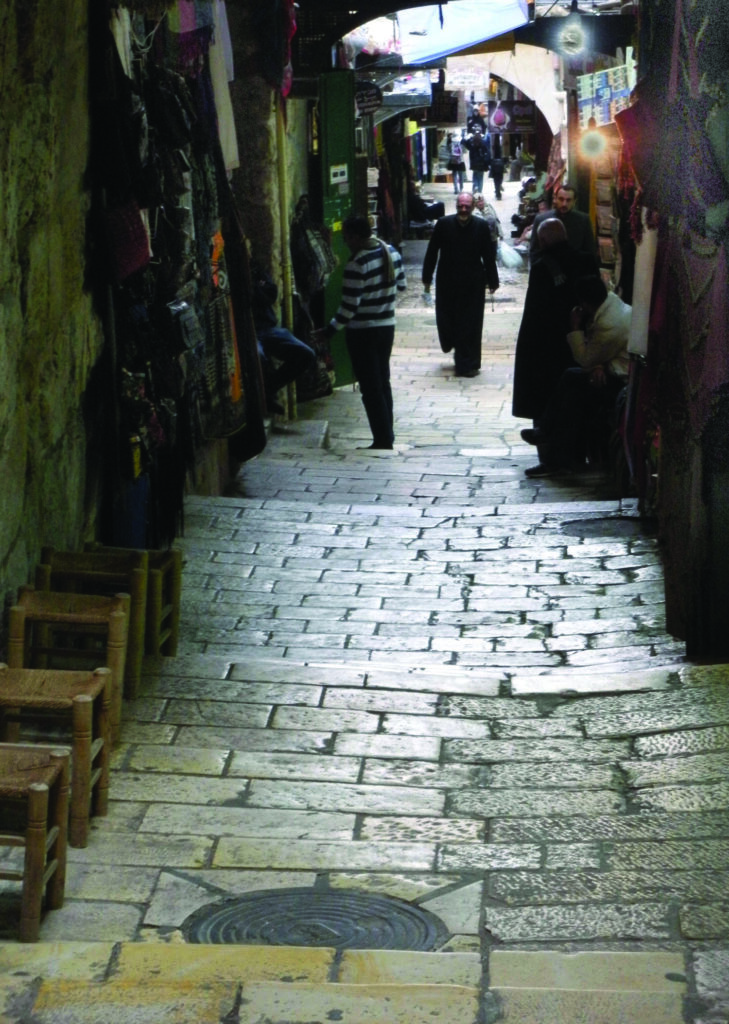

—Proclaimed the actual path Jesus took on his way to the cross, the Via Dolorosa, and declared the precise spots of all of the fourteen Stations of the Cross;

—Found at least several pieces of the true cross itself;

—Identified the spot near the Sea of Galilee where the miracle of fish and loaves occurred;

—Confirmed the place where Jesus stood when he gave his Sermon on the Mount;

—Marked the place of the Annunciation, where Mary learned that she would give birth to Jesus;

—And she also identified places where Joseph’s carpentry shop stood, where Jesus was born, the field in which the shepherds saw the Bethlehem Star, and the inn of the Good Samaritan.

The story of Helena’s pilgrimage is certainly not fantasy. In his Life of Constantine (c. 340 AD), Eusebius wrote (only about ten years after her death) that Helena lavished good deeds on the Holy Land, and “Although well advanced in years, she came, fired by youthful fervor, in order to know this land” and she “explored it with remarkable discernment…And by her endless admiration for the footsteps of the Savior…she granted those who came after her the fruits of her piety. Afterward she built two houses of prayer to the God she revered, one in the Grotto of the Nativity (this is the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem) and the other on the Mount of the Ascension (this is the Eleona Church on the Mount of Olives).” Helena also is said to have identified the spot where Jesus was crucified and buried, and ordered the first Church of the Holy Sepulcher to be built there.

It is a matter of some interest that while Helena’s important pilgrimage is well documented, not a single numismatic memento of these events was issued. So the coins of Helena can only offer us a glimpse of the appearance of this important woman of antiquity.