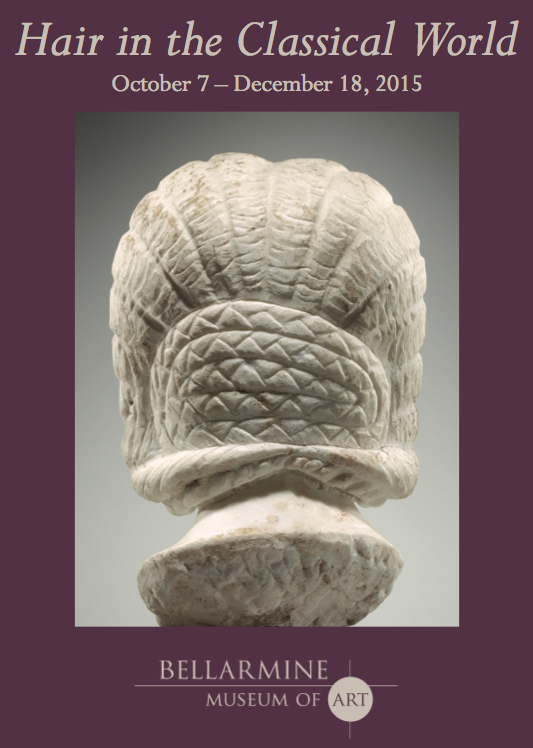

Hair in the Classical World

The Bellarmine Museum of Art at Fairfield University has just opened a fascinating new exhibition with the theme of “Hair in the Classical World.” On display in the gallery are an assortment of objects and images from the Bronze Age through late Antiquity, including a diverse array of sculptures and, of course, coins. As the introduction to the exhibition notes, hair is particularly “resonant of cultural identity,” and the way that it was styled and sported in antiquity served a variety of different purposes. Among other things, hairstyles signified social position, served as a medium of cultural exchange, and played an important role in various rituals and rites of passage.

One of the most compelling aspects of the exhibition is its manifest interdisciplinarity. Any consideration of hairstyles must necessarily draw upon a wide range of material, historical, and visual sources, and the interpretation effectively mixes insights from archaeology, art history, and cultural studies. As everything from the intricate hair pins on display to the careful texturing and arrangement of hair on the statuary suggests, hairstyles were an important means of self and artistic expression in the classical world.

A significant inspiration for the exhibition was the Caryatid Hairstyling Project, which employed a professional hairstylist and student models in an attempt to replicate the elaborate hairstyles on the famed marbles of the Erechtheion. A short film of that project is on view as part of the exhibition. While all of this might give the impression that the focus is exclusively on women, there is also material reflecting on men’s hairstyles, which at times were as elaborate as those that adorned women. Braids were one style common to boys and girls in ancient Greece. Grown out along the central part, the braid was ritually cut and dedicated to the goddess Artemis when entering adulthood.

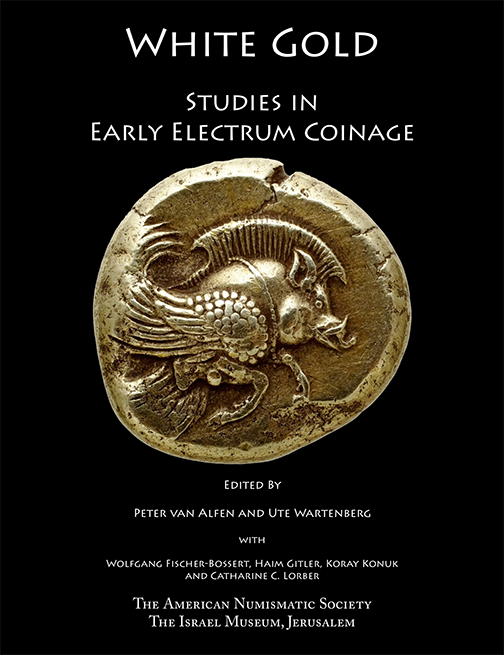

The reason we are writing this up here is of course because coins feature prominently in the exhibition. The curators liken coins to the social media of today insomuch they were a medium through which images of hairstyles circulated and reached a wide audience.

The American Numismatic Society has ten coins on loan to the Bellarmine Museum for the exhibition, including a silver decadrachm from Syracuse, a denarius of Julia Domna and a gold aureus of Faustina the Younger. Coins were a form of propaganda and a way to project power in the classical world, and the variety of hairstyles captured in the portraits reflect the politics and fashion of their age. Perhaps the pièce de résistance in terms of the coinage is a silver decadrachm that features a portrait of the water nymph Arethusa wreathed by swimming dolphins. It was minted in Syracuse between 405 and 400 BCE, when the city-state was ruled by the tyrant Dionysius. In an attempt to buttress his reputation and power, he engaged the best engravers available to produce some of the finest coinage anywhere in the Greek world.

“Hair in the Classical World” will be on view through December 18, 2015, and the Bellarmine Museum is free and open to the public (see here for hours and directions). It should also be noted that the museum will also be hosting a scholarly symposium on the subject on the afternoon of November 6. Speakers include Dr. David Konstan from New York University, author of Beauty: The Fortunes of an Ancient Greek Idea (2015) and Janet Stephens, a Baltimore-based hairdresser and amateur forensic archaeologist. To pre-register for the symposium and to see more information about other public programs connected to the exhibition, head here.