Emancipation Day Token: Sarah Ann Prout

Sutlers were civilian merchants who supplied the Union Army with non-military goods that the government did not provide for the troops. Each military post had a designated sutler and although their activities were supposedly governed by the Federal Army Regulations of 1861, in practice they did what they pleased. Beyond standard necessities like clothing, kitchenware, and foodstuffs, they also stocked pipes and tobacco, playing cards, writing materials, books, newspapers, and other sundries that the huge camps of men mobilized for the war required.

The article that accompanied the illustration above described the sutler as a “necessary evil” of army life. Because they were civilians whose primary motive was profit, sutlers could charge inflated prices and ensnare soldiers in credit schemes. Although officially prohibited, alcohol was a bestseller and contributed to their unsavory reputation, as bribes and smuggling quickly became standard operating procedure. Wherever the Union Army marched, the sutlers followed, selling their wares out of wagons, tents, and other temporary structures like the operation run by A. Foulke at a military camp in Virginia, ca. 1863-64.

As most posts had only a single appointed sutler, they faced no competition and a combination of exorbitant prices and poor merchandise often led to strife and raids by angry soldiers. In short the sutler system was something of disaster throughout the war and the morale and discipline problems it created were so pernicious that it was abolished in 1866.

What concerns us here were some of the interesting numismatic dimensions of the sutler system. Perhaps most notable in this regard were so-called ‘sutler tokens,’ which were essentially a way of extending credit to soldiers between paydays. Issuing tokens also prevented soldiers from spending their money elsewhere and more practically alleviated the acute lack of circulating currency in camp. Tokens and cardboard scrip issued by sutlers were oftentimes the only kind of small change available and they were the primary means through which business was transacted in camp.

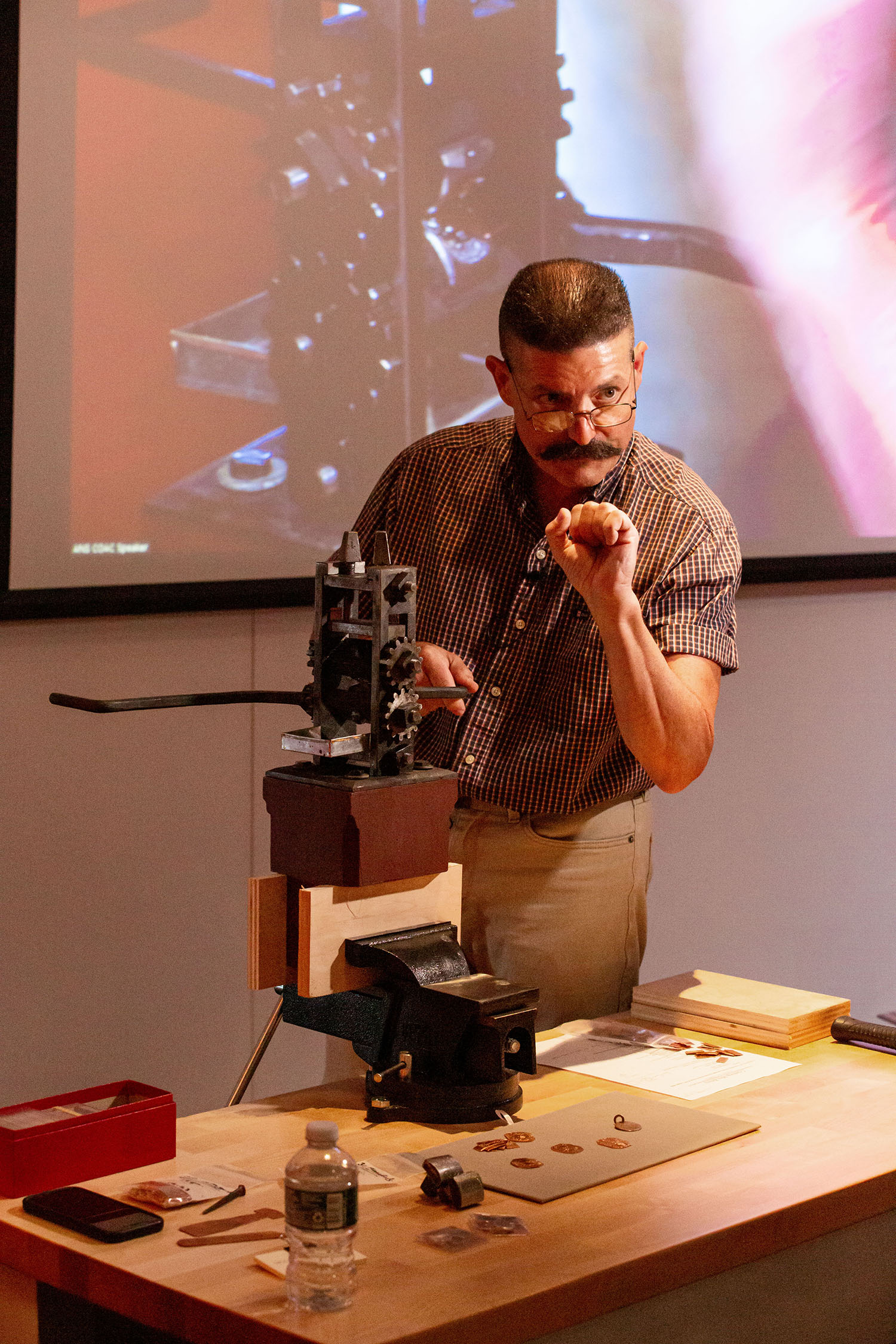

These thin brass tokens typically had the name of the sutler and the unit on the obverse and either a generic pattern or the mark of its maker on the reverse. The token above was struck by John Stanton in Cincinnati for J. L. Cooper, the sutler for the 2nd Regiment of the Ohio Cavalry. The general rarity of these tokens has inspired a community of Civili War-era collectors, but they were not the only numismatic objects related to sutlers.

One item that came to be sold by most every sutler were identification discs, which were an early version of what we now know as “dog tags.” As soldiers came to realize the brutality of the conflict and the near impossibility of being identified in the event of their death, a durable means of identifying oneself in case the worst happened was sought. A wide variety of solutions were used, from stencils used to ink names on clothes to preprinted paper tags that could be filled out and attached with wire. Any bit of metal that could be repurposed with a bit of engraving was tried and so an assortment of metal badges and pins appeared, but the most popular solution proved to be small brass coin-like tokens. These discs bore patriotic symbols or busts of renowned Americans on their obverse with the reverses left blank for stamping on identification information. A hole drilled in the top allowed it to be securely fastened to a uniform or worn as a necklace.

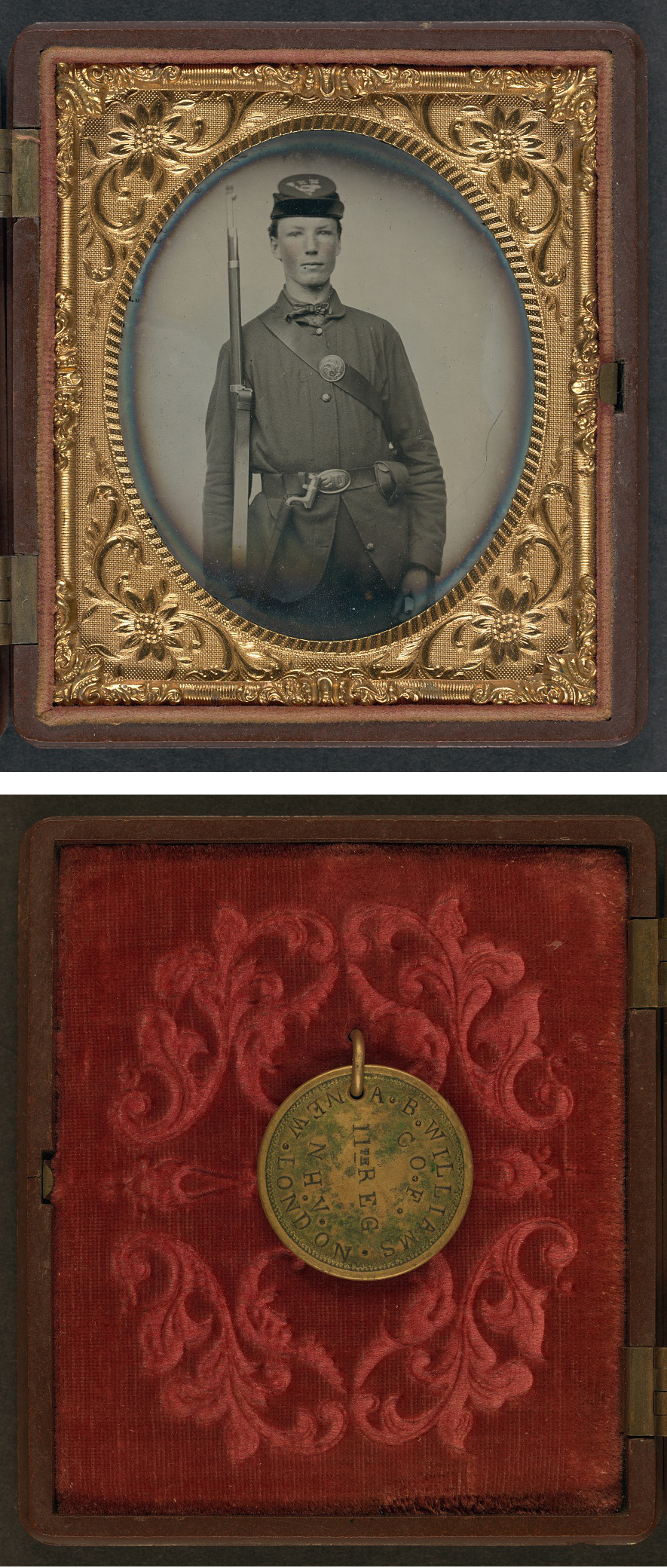

Their utility was borne out in battle. The cased tintype at left from the Library of Congress pictures Corporal Alvin B. Williams, who enlisted at the age of eighteen and was killed in May 1864 at the Battle of Spotsylvania. Although the precise circumstances of his death are unknown, the case poignantly contains his identification disc, which might have been the only means by which he could be identified amidst the carnage of that particularly bloody battle. Williams was originally buried at Beverly’s Farm, but his remains were later relocated to the Fredricksburg National Cemetery. Because these brass discs were relatively cheap, they proved popular with the troops and sutlers concomitantly stocked them in many different styles. Discs with assorted obverse designs and blank reverses were purchased wholesale from die-sinkers in New York, Boston, and other locales, and then the sutler finished the work at the point of purchase by stamping letters on with metal punches. Maier and Stahl’s research suggests the sutlers bought the blank discs for about a dollar each and then sold them to soldiers for two or three dollars, a seemingly fair mark-up, at least by contemporary sutler standards. The finished product looked something like this:

Note that in this case the reverse was not simply blank but pre-stamped with certain generic information, which made finishing the work with punches much easier.

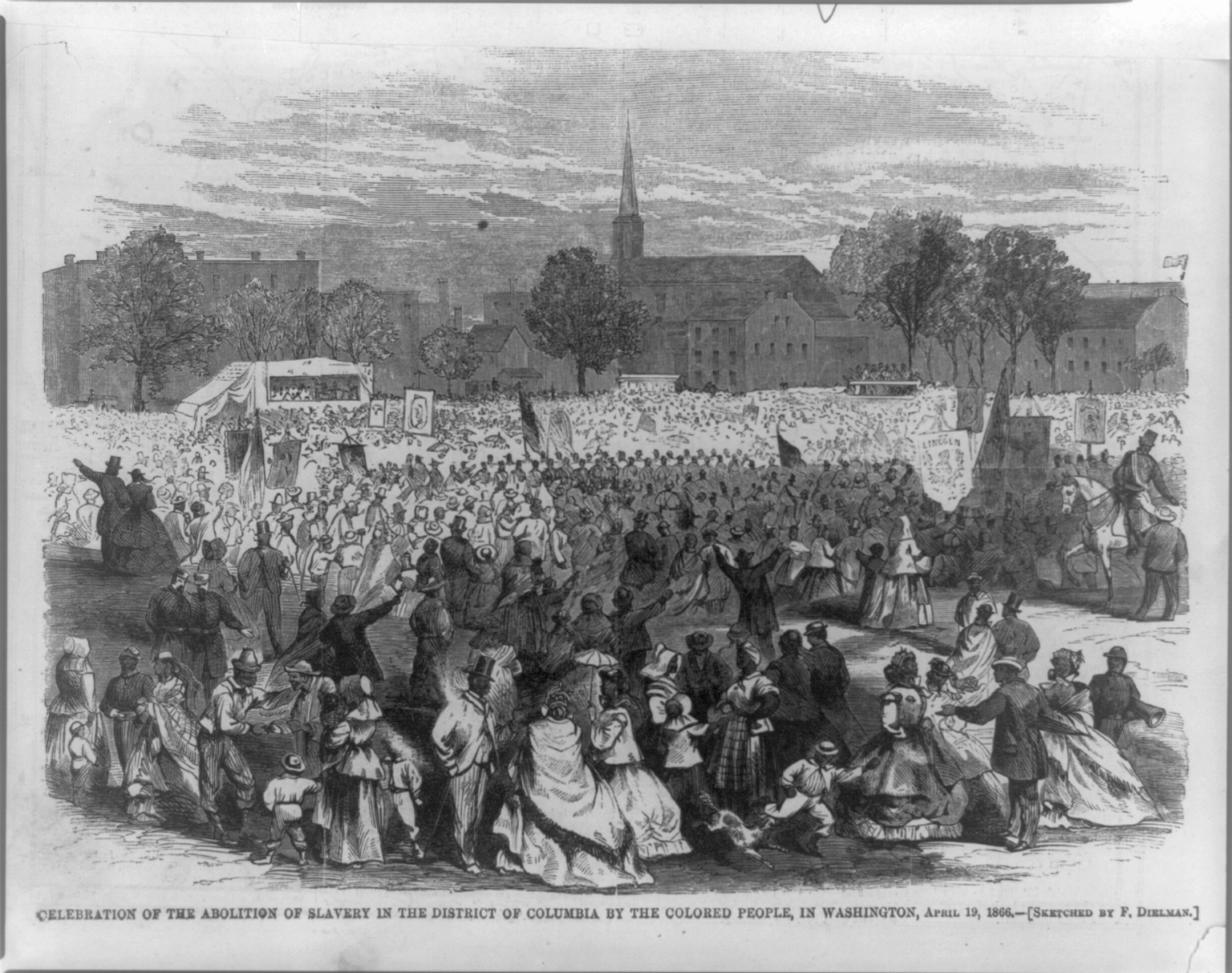

The American Numismatic Society has dozens of identification discs, each possessing its own interesting story, but the one I want to single out was not sold to a soldier. It was inscribed with the name of a woman named Sarah Ann Prout on the occasion of the passage of the District of Columbia Emancipation Act, which was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on April 16, 1862. The act was a notable precursor to the Emancipation Proclamation and the debates that surrounded it. This was in a sense a model piece of legislation in that it combined emancipation with compensation to slave owners, and also provided funds to newly freed slaves willing to emigrate abroad. The act obviously had the most direct impact on the three thousand or so slaves in the District of Columbia who were freed, but its passage was celebrated by African Americans and abolitionists around the country. The jubilation was such that Sarah Ann Prout went to a sutler and had this disc stamped to mark the day.

Who was Sarah Ann Prout? The likeliest candidate that I have been able to find is a “Sarah Prout” enumerated in the 1860 census. She was then a 33-year-old African-American woman living in Millersville, Maryland about twenty five miles east of Washington, DC. Listed as a “Free Inhabitant” of the state, her occupation was given as “Farm Laborer.” As detailed on the handy Legacy of Slavery in Maryland website, the slave (87,189) and free (83,942) black populations were then roughly equal in Maryland. I do not presently have access to some of the more specialized research tools and databases used by historians and genealogists so perhaps this identification is in error, but of the Sarah Prouts listed in the census she seems to make the most sense in terms of both background and geography. Perhaps she was attracted to work in the burgeoning military camps and complexes that sprang up around Washington as the war effort expanded. The passage of the Emancipation Act would certainly have been an occasion for celebration by the black community in and around the District of Columbia. Moreover there is always the possibility that this Sarah Prout, although free in 1860, was born into slavery, which would make the day particularly redolent. While this presupposes much, the token was certainly purchased by someone for whom the Emancipation Act was a significant event, and perhaps further research will tell us more about Sarah Ann Prout’s experience.

As it was in many other African American communities around the United States, the day of emancipation subsequently became something of an annual holiday that was celebrated with a festival and parade. Indeed, it is observed in Washington DC to this day.

If a reader has any ideas or suggestions on tracking down more information about Sarah Ann Prout, please just email me here.

For more on sutlers and Civil War-era numismatics see Francis Lord, Civil War Sutlers and their Wares (1969); David E. Shenkman, Civil War Sutler Tokens and Cardboard Scrip (1983); Larry B. Maier and Joseph W. Stahl, Identification Discs of Union Soldiers in the Civil War (2008).