Medallic Representations of Dance in Fin de Siècle France

by Scott H. Miller, ANS Life Fellow

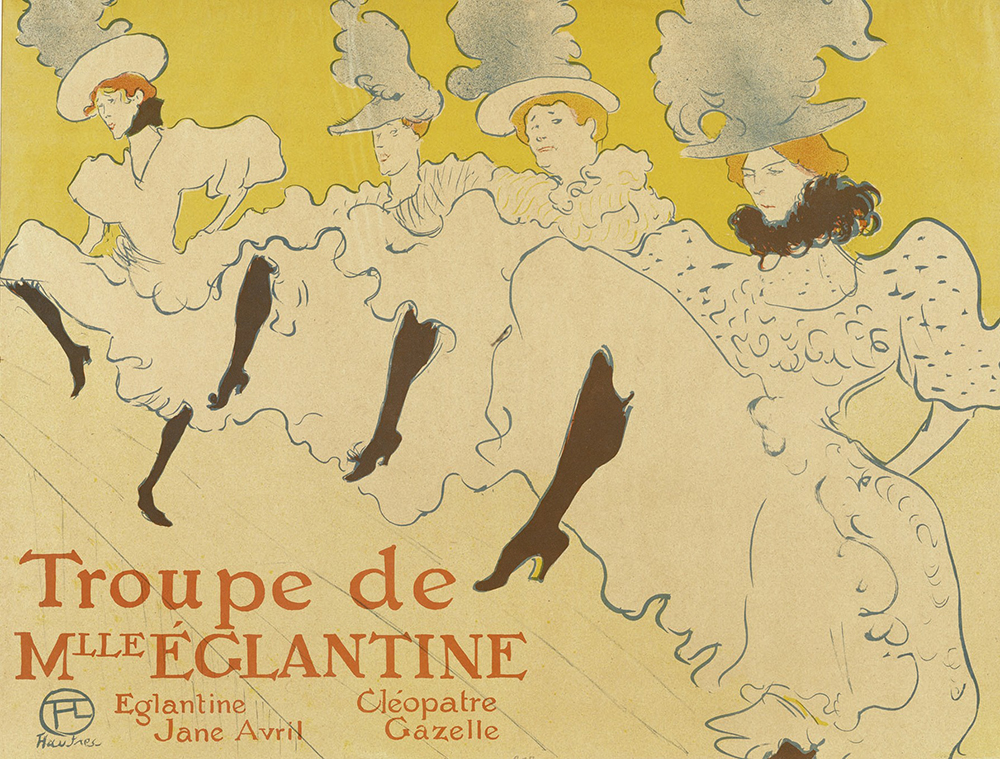

In our early twenty-first century world, where performance is often seen digitally, we tend to forget that only a century ago entertainment was still live—though about to be replaced by movies and radio. Then, as now, actors and singers were household names, and the experience of seeing a big name might leave an impression remembered for a lifetime. Some of our most enduring, popular images of France during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries revolve around images of the dance, most notably the infamous Can-Can, long associated with the Moulin Rouge, though not exclusive to it (fig. 1).

There was also the Folies Bergère, well past its prime, but still around today. Perhaps the most widely known, popular image is a work of the impressionist painter Edgar Degas. Although Degas created many paintings depicting dancers throughout his career, his best-known work, and one which has captured the public’s imagination as personifying the age is his statue of the Little Dancer, which was first shown at the Sixth Impressionist Exhibition of 1881, and more recently in the popular television series The Gilded Age (fig. 2).

As with other forms of decorative art in turn of the century France, medals were a part of popular culture just as they were a part of the art world. Whether produced for widespread distribution, or in limited numbers, they remain as contemporary illustrations of iconic people and events which help define the popular idea of France during the Belle Époque. Though little known today, it should not come as a surprise that dancers were a common theme for medals created during the period. The Société des Amis de la Médaille Française (SAMF) was the brainchild of Roger Marx, who was employed by the French government as Inspecteur Général des Musées des Départements (fig. 3).

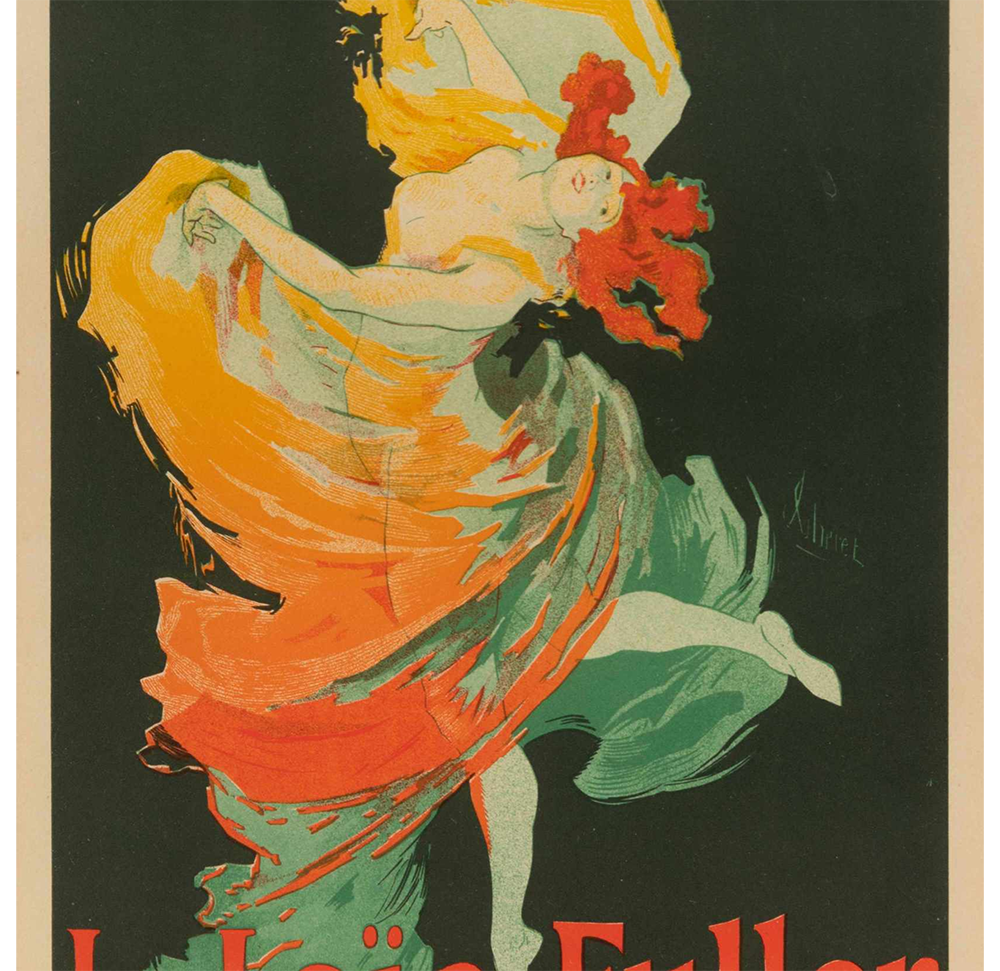

He was also one of the great promoters of decorative arts, including posters, prints, and medallic art. Founded in 1899, the SAMF issued several medals each year, examples of which were available for purchase by members in silver and bronze. A medal by Pierre Roche was issued at the time of the 1900 Universal Exposition then being held in Paris. It depicted Loïe Fuller, who was then performing at her own theater within the Exposition, designed by Henri Sauvage and which featured sculptures by Roche at the entrance (fig. 4). Her performances made innovative use of free movement, as well as color and lighting.

Fuller was born Marie Louise Fuller in Illinois in 1862. She began her career as a practitioner of free dance in burlesque, vaudeville, and other popular venues, but moved to France in 1892 because she felt she was not appreciated sufficiently as a serious artist in the United States. She regularly performed at the Folies Bergère, and became a popular subject for posters and sculpture, including works by Jules Chéret and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. While Fuller’s prominence in the contemporary Parisian culture in 1900 might have been sufficient for her placement as the subject of Roche’s SAMF medal, her personal friendship with both Roche and Marx were almost certainly contributing factors as well.

The medal itself measures 71 mm. The obverse depicts Fuller dancing, along with her name, while the reverse depicts two calla lilies, crossed and elaborately tied with a ribbon, apparently in reference to Fuller’s Lily Dance (fig. 5). A total of 275 medals were struck, of which 157 were in bronze and 109 in silver, with a small number in other metals.

The Cleveland Museum of Art has in its collection a number of items relating to Loïe Fuller, as well as several pieces donated by her. Included in the museum’s collection are a pair of uniface casts of this medal, the obverse being 19.1 cm, and the reverse 18.1 cm (1978.120.a, 1978.121.a). Other Fuller-related items in their collection include a color lithograph by Henri Toulouse-Lautrec (1925.1202), a 53.4 cm high bronze statue of a standing Loïe Fuller, donated by the subject in 1917 (1917.368), a 1904 book by Pierre Roche entitled La Loïe Fuller (1995.54), and a 68 mm medal of Orpheus by Lucien Coudray, awarded to Loïe Fuller (1978.116).

Another American dancer whose performances proved popular in France was Isadora Duncan. Angela Isadora Duncan was born in San Francisco about 1878. As with Loïe Fuller, Duncan did not feel appreciated in the United States and moved to England in 1898, and then to France two years later, where her uninhibited, improvisational and free-style dance proved popular.

Her dress, as well as her movements, were inspired by depictions of ancient Greek art. Duncan was as unconventional in her personal life as in her professional one, ultimately giving birth to three children, all out of wedlock. As with Fuller, Isadora Duncan was a popular subject for artists. However, while Loïe Fuller remains an icon of turn of the century Paris, Duncan, whose popular image has not survived as well, has retained better name recognition nearly a century after her death in a freak accident in 1927.

In 1912, Victor Canale published a 100 mm uniface plaque of a dancer by the then young sculptor, Henri Dropsy. In a 1964 catalogue of Dropsy’s work, this medal was described as having been inspired by Isadora Duncan, who gave, at that time, memorable representations of dance. The medal depicts Duncan in her Greek inspired costume, dancing in the free-spirited style for which she was known (fig. 6).

While many artists created the occasional work related to dance, Maurice Charpentier-Mio spent a good part of his career depicting aspects of the dance, most notably Isadora Duncan and the Ballets Russes (fig. 7). Maurice Charpentier (1881–1976) added Mio after his name sometime about 1913 in order to avoid confusion with other sculptors bearing similar names, most notably Alexandre Charpentier and Felix Maurice Charpentier. Even that was not enough, as confusion between the three still occurs.

The Ballets Russes was an itinerant ballet company that gave its first performance in Paris in 1909 under the direction of its founder, Sergei Diaghilev. Most of the original performers were members of the Imperial Ballet of Saint Petersburg who worked for Diaghilev during the off-season. In popular culture, the Ballets Russes maintained an image of high-brow culture, even making it into the theme song of the Patty Duke Show, which aired from 1963 to 1966. In 1931, Belgian medalist Godefroid Devreese created a plaquette entitled Pastorale-Ballets Russes. Pastorale, which was first performed by the Ballets Russes in 1926, was composed by Georges Auric, with choreography by George Balanchine.

In addition to the depiction of specific dancers, a number of medalists of the period used the theme of dance as a general subject, avoiding specific dances or performers. Perhaps the best known was Alexandre Charpentier, who visited the theme on several occasions, as with this pair from the collection of the American Numismatic Society (fig. 8).

While the billowing fabric might be a slight nod to popular dancers, such as Loïe Fuller, the performers’ nudity makes it clear that these are not public performances, but more in line with traditional sculpture of the period, which often presented nude women as simultaneously seductress and chaste. As with many similar pieces by Charpentier, these would have been available as both stand-alone works of art, or as inserts for furniture or hardware for the home. In this case, these plaques, along with two depicting nude, female musicians, were inserted in a music cabinet, now in the collection of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs.

Other medalists who approached dance as a subject for art medals did so as a generic theme, rather than illustrations of specific dancers. François Rupert Carabin, who created a series of six bronze figures depicting different phases of Loïe Fuller performing her Serpentine Dance, chose to depict a more generic image. Issued in 1901, this 50 mm medal was simply titled The Dance (fig. 9). On the obverse, Carabin depicts a woman on what appears to be a stage, while the reverse shows two couples dancing. Taking a different approach, Charles Pillet produced a plaquette for SAMF with the title Enfants (fig. 10). One side depicts four young children dancing in a circle, the models for which were probably his own children.

After World War I, medals began to lose popularity, and rarely depicted current, cultural trends. However, during that brief period, we think of as the Belle Époque, when artists, collectors, critics, performers, and the audience all came together, it is gratifying to know that medalists had their place at the table, next to a glass of absinthe.