Mysteries from the Vault: A Roman Lead Token from Hispania Baetica

The dating, function, and iconography of Roman lead tokens from Spain have been objects of speculation among scholars for decades. Several of these tokens, with weights ranging from 4–400 grams, have been found in the Spanish region of Cordova, once part of the Hispania Baetica, an area known in Roman times for silver mines. Spanish silver mines were one of the most important sources of silver bullion for Rome, and the connected smelting activities took place on such a huge scale that the lead pollution generated by them is still traceable in the Greenland ice core. At the same time, Baetica was also an important producer of olive oil, traded all over the Mediterranean Sea. Spanish lead tokens then, made out of a by-product of silver smelting but possibly also connected to agriculture, represent a useful yet poorly understood tool to understand the economic organization of this province.

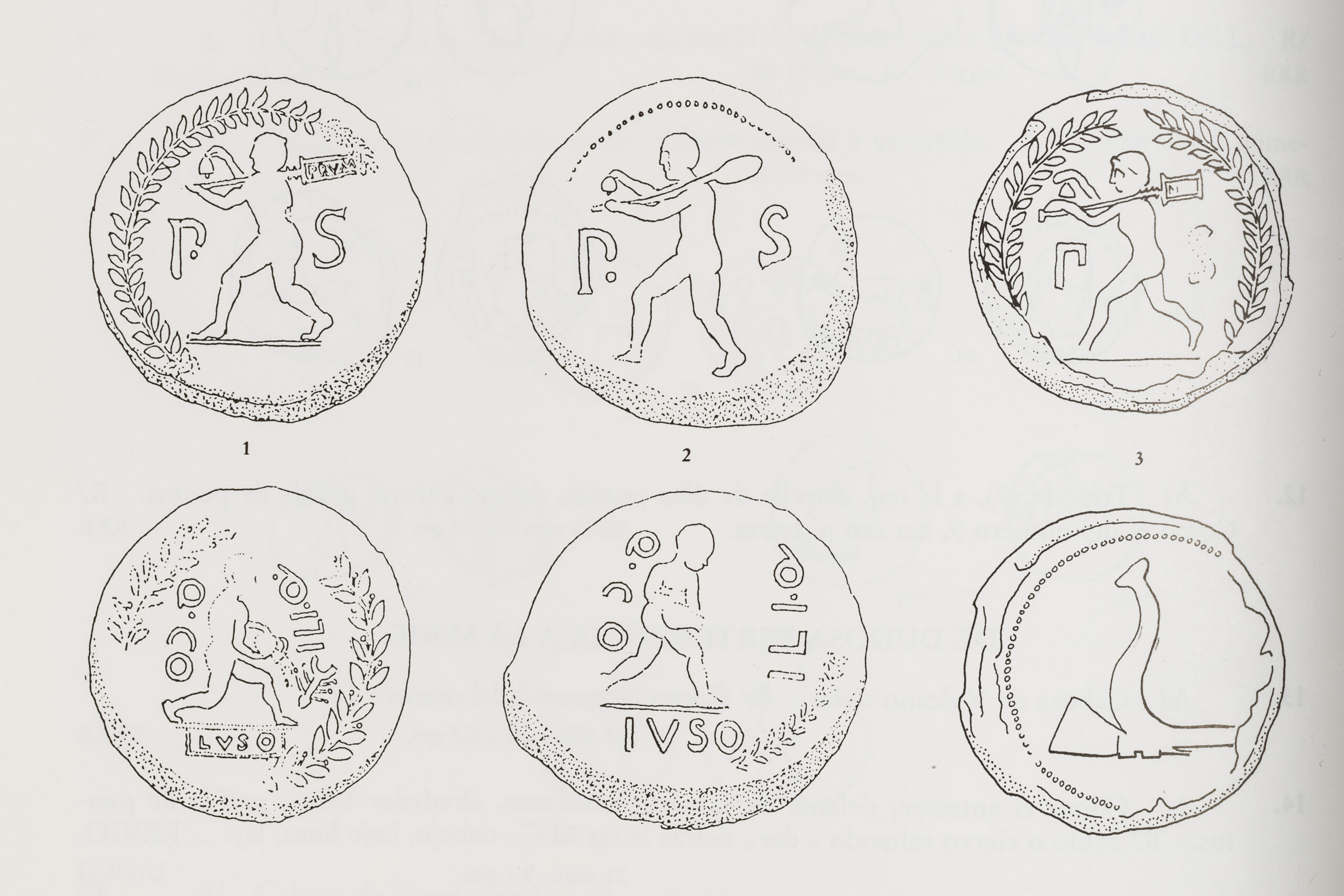

The Richard B. Witschonke Collection at the ANS includes 16 specimens of these tokens, nine of which remain unpublished. One of them (fig. 1) is a unique piece, part of lot of 10 Spanish lead tokens offered for sale in CNG MBS 67 on September 22, 2004 (lot nos. 1070–1079). The CNG catalogue offers the following description:

Obv. Nude male walking left, carrying bell(?) and shovel over his shoulder; P · S across field; all within wreath. Rev. Harrow (or miner’s axe?). Weight: 166.78 g

The identity of the man represented on the obverse, together with the function of the objects he is carrying, is a mystery. Is he a miner, carrying a shovel? This is the interpretation offered by F. Casariego, G. Cores, and F. Pliego, who first published this piece in their catalogue of Iberian lead tokens from Roman times. They classified this piece as part of the series de las minas (“mines series”), conventionally related to the Roman mining operations in Baetica. These mine tokens (figs. 2, 3, 4) are usually characterized by the presence of a man with a “shovel” (a conventional term; it is unclear what this is).

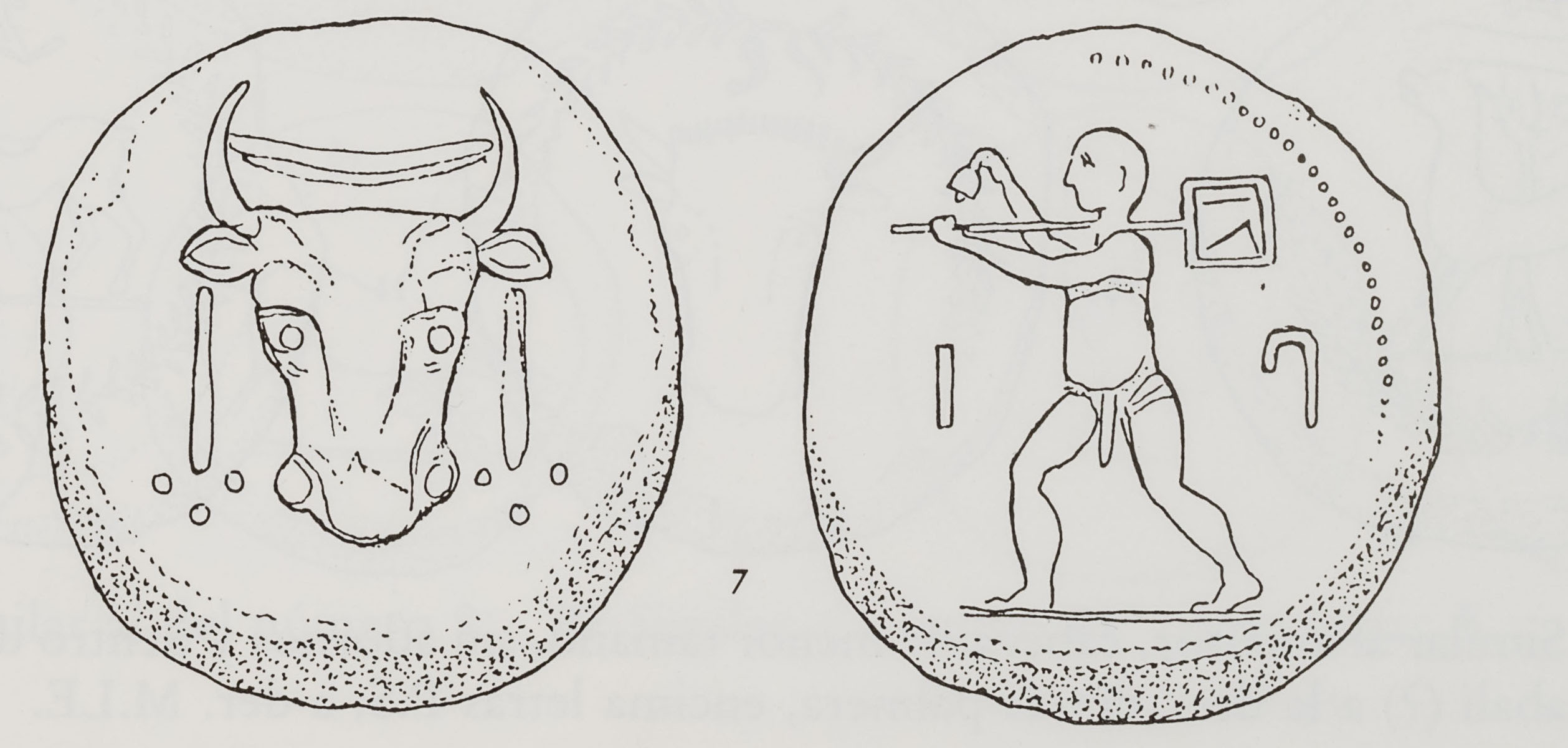

This representation closely resembles the miners portrayed on the Linares bas-relief (fig. 5). Moreover, some tokens of the series de las minas were found in the Roman mines of El Maderero (fig. 6) and of Posadas (fig. 7), both in the Baetican district of Cordova. The archaeological context suggests a dating in the first century BC for these tokens. According to this interpretation, these tokens may have served as a ‘company coinage’ for these mines, a practice well attested in modern times. This token and the others of the “mines series” would therefore be one of the first instances of this use of tokens.

However, some elements in the iconography of the token represented in fig. 1 do not seem to match this interpretation. The bell carried by the man with the “shovel” and the arrow on the reverse need to find an explanation. A possible solution for this enigma does not come from Spain, but from Central Italy.

In a series of articles, C. Stannard showed the certain iconographical relationship between lead tokens from Baetica and local bronzes from Central Italy. The motif of the man with the “shovel” is attested in the area of Minturnae, Naples, and Pompeii, where no connection to mining activities can be made (fig. 8). The man with the “shovel” was probably not a miner, after all. As represented in fig. 4, the most frequent iconography of this figure is a walking man, either naked or wearing a short tunic, carrying the “shovel.” In the Italian material, he often also carries an askos, an oil or wine jar; in the Baetican, a bell (as in the case of the token in fig. 1). Could the man with the “shovel” be a farmer? The farming context could help explaining the presence of a harrow on the reverse of our token. Moreover, M. P. García-Bellido argues that the letters P · S, appearing on the token at ANS and on other ones of the same series, could be interpreted as P(ublica) S(ocietas), a State-owned enterprise exploiting oil-production in Baetica. According to this second interpretation then, the tokens of the series de las minas were used as a “company coinage” in an agricultural context, not in a mining one.

The iconographical similarities between Baetican tokens and Italian bronzes bear testimony to the active commercial relationships between Italy and Baetica in the Age of High Empire (first–second centuries AD), especially wine and oil trade. Mount Testaccio in Rome, an artificial mound composed almost entirely of testae, fragments of broken oil and wine amphorae dating from the first– third centuries AD (figs. 10, 11) bears testimony to the enormous scale of this trade. While researching Mount Testaccio’s amphora stamps, B. Mora Serrano (fig. 9) noticed the correspondence between the names appearing on some tokens of the series de las minas and the ones on amphora stamps from Testaccio. He therefore argued that at least some of the Iberian lead tokens of the series de las minas are connected to the transport of the Spanish olive oil to Rome. It follows that the man with the “shovel” on the unique piece of the Richard Witschonke Collection would not be an Iberian miner, but rather an Italo-Baetican farmer, probably occupied in producing wine and oil to export to Italy.

However, neither the presence of a bell nor the generously ithyphallic representations (cf. fig. 4) of the man with the “shovel” are addressed by this interpretation. C. Stannard argues that these elements could be explained if these figures were mimes. The Roman mime differed from Greek Comedy in that actors did not wear masks, as in the images on the Iberian lead. According to Stannard’s hypothesis, the man with the “shovel” represents a mime, a decorative element on tokens that were used as a “company coinage” in the context of an Italo-Baetican oil-trade enterprise.

In sum, the identity of the man with the “shovel” on the token presented in fig. 1 raises historical and iconographic questions that show the strength of the commercial and cultural interconnections within the Roman world. Were the tokens of the series de las minas really connected to mining activities, as their findspots seem to suggest? Or were they connected to the trade of Spanish oil, as B. Mora Serrano posits? The debate is still open.

Two elements still need further interpretation:

- Even if not univocally linked to mines, some tokens of the series de las minas did circulate in mining areas. It is therefore not possible to entirely dismiss the “mining” interpretation.

- The findspots of some tokens of the series de las minas show that these kind of tokens were already circulating during the first century BC, so they could not be directly linked to the Spanish oil trade of the first and second centuries AD.

Not all the questions are solved, then. The mystery of “our” man with the “shovel” is still intact.

New hypotheses on the iconography and the function of the man with the “shovel” and the function of the fascinating Spanish lead tokens will be formulated at the interdisciplinary conference “Tokens: Culture, Connections, Communities” at Warwick University (June 8–10, 2017), where all the published and unpublished lead tokens from the Richard W. Collection will be presented.