Admit One: Sprague & Blodgett's Georgia Minstrels

One of the most popular and complicated cultural forms that enlivened popular entertainment in the nineteenth-century United States was the minstrel show.

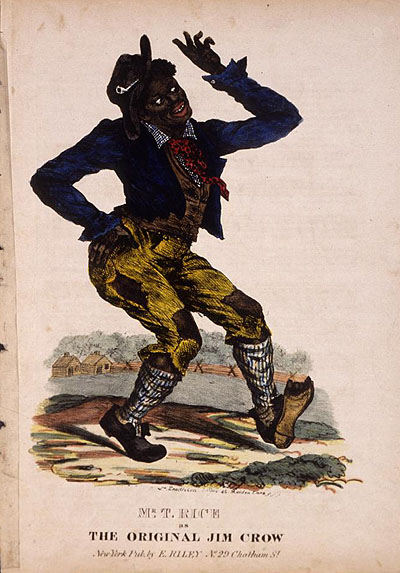

While musicologist Dale Cockrell has usefully detailed the longer historical trajectory of blackface performance in the United States, the immediate origins of the minstrel show rested on the spectacular success of Thomas Dartmouth Rice’s performance of “Jump Jim Crow” in the late 1820s and 1830s. This was a ribald song-and-dance routine that Rice, a white actor, performed dressed as a ‘black’ man in tattered clothes with his face blackened with burnt cork. His success opened the floodgates of blackface entertainment as white performers and musicians all over the country began ‘blacking up.’ By the 1840s, groups like the Virginia Minstrels and Ethiopian Serenaders were offering full evenings of entertainment know as minstrel shows that featured a mix of songs, dances, and skits.

Blackface minstrelsy was the most popular form of entertainment in the United States during the mid-nineteenth century, but the racial elements that it embodied and transgressed have made it a source of continuing controversy. Many early scholars looked at the minstrel show as an honest representation of black folk culture, which was a perspective that echoed the claims of contemporaries. Other scholars have argued that the minstrel show was a caricature of black life that effectively denigrated blacks and legitimized white supremacy. Part of the problem with trying to understand minstrelsy is that it proved so durable over time, and found such a broad audience, that it makes any overarching interpretations about its meaning problematic.

One particularly difficult thing for many people to understand is how and why African-American performers began to appear in minstrel shows in the decades after the Civil War. The reasons were of course manifold and complex, but essentially there was an opportunity because minstrel shows were a form of entertainment that already featured ‘black’ performers. African-Americans were able to capitalize on white fascination with black life by playing up their novelty as “genuine Negroes” and offering ostensibly authentic performances of plantation life in contrast to the “counterfeits” of white minstrels. Because of its association with the South and slavery, the moniker “Georgia” came to signify that a minstrel troupe was made up of African-American performers. The formula proved strikingly successful, and by the 1870s there were a number of black minstrel troupes touring the United States, despite what was often an acrimonious relationship with the white theatrical establishment.

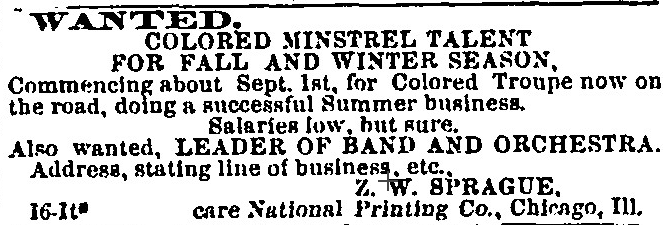

It was in this context that the Sprague & Blodgett’s Georgia Minstrels known to numismatists came about. Z. W. Sprague was a longtime manager of white minstrel troupes associated with the city of Chicago. Wash Blodgett was an agent for assorted traveling entertainers, most notably working for the magician and ventriloquist DeCastro. During the summer of 1876, Sprague took out an ad in the New York Clipper, the semi-official organ of the American show trade, looking for black performers. Although listed as co-proprietors, it seems that Sprague financed and organized the troupe while Blodgett was the agent who actually traveled with it. The manager of this initial iteration of Sprague & Blodgett’s Georgia Minstrels was the notable African-American performer Charles B. Hicks.

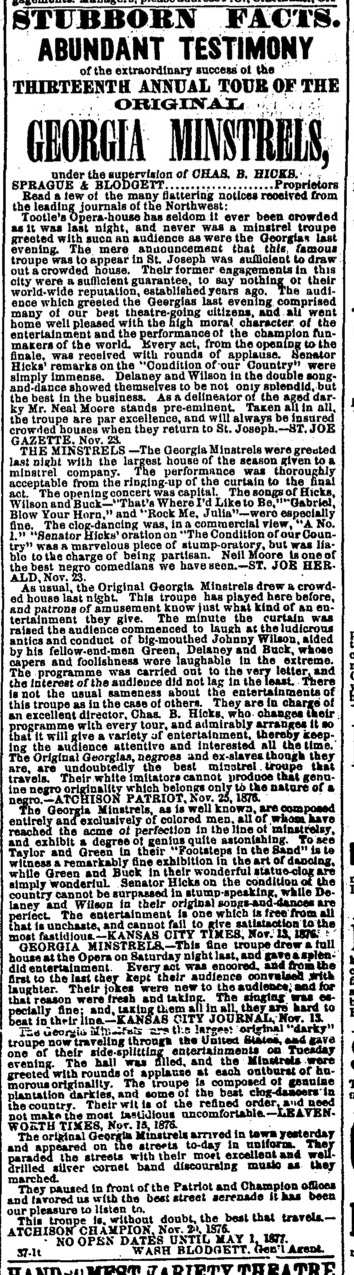

Hicks had been one of the originators of African-American minstrelsy and was able to put an impressive array of talent together for the ongoing tour. In late December, the troupe took out an advertisement in the New York Clipper that trumpeted its success and reproduced fawning press notices.

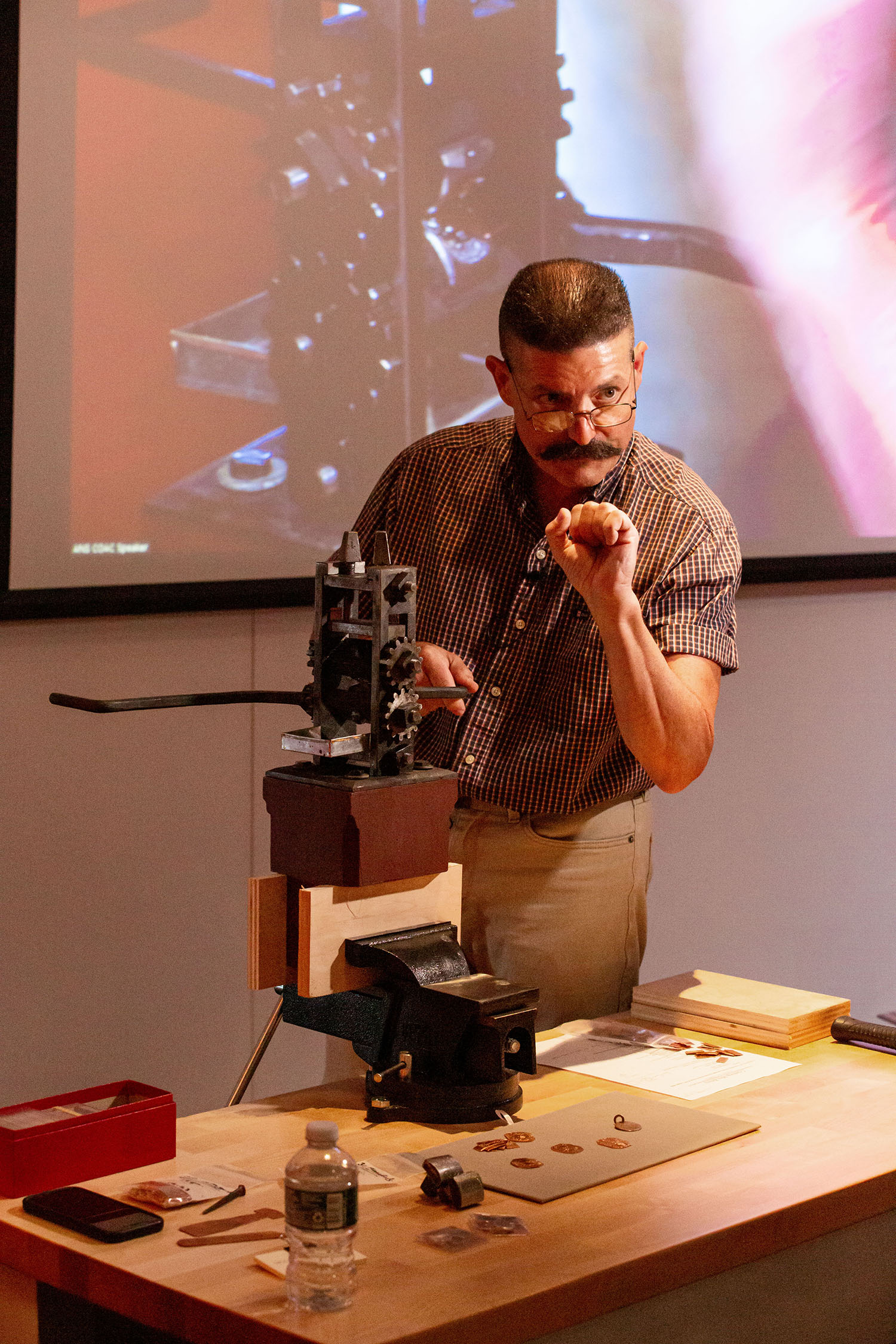

Although Hicks soon left the troupe, many of the most celebrated black entertainers of that era, including James Bland and Sam Lucas, performed with Sprague’s show. Sprague’s association with Blodgett was likewise short-lived, and by June 1878 the latter’s name was dropped from the advertising. The countermarked coins associated with Sprague & Blodgett were thus produced sometime between the fall of 1876 and the spring of 1878. In Gregory Brunk’s comprehensive catalog of countermarked American currency, he lists ten specimens of the countermark on Liberty Seated half dollars, with a date range from 1862 to 1877. The ANS specimen is an 1877 half dollar minted in Carson City, Nevada.

It is not clear precisely how these countermarked coins were used. While they obviously served as a kind of admission check for the show, the denomination of the host coin was actually the same price (50¢) as a ticket for the performance. In this context it seems likely that they were distributed by an agent of the Georgia Minstrels to get favorable publicity from the press or to ensure the goodwill of the local community by giving away some free ‘tickets’ to the show. Although a few circus countermarks are known, this seems to have been the only minstrel troupe to use them.

Sprague sold out his interest in the Georgia Minstrels to Richards & Pringle in 1880, but the show continued under that title into the twentieth century. Over time, black performers undermined and eventually exploded many of the impoverished white-controlled representations of African-Americans that minstrelsy had introduced into American culture. This countermarked coin is a material reminder of the complex legacy of the minstrel show, and the dynamic but often painful interactions between white and black Americans that have animated U.S. popular culture.

The best history of the minstrel show in the United States is Robert Toll’s Blacking Up (1974), but perhaps the most compelling work on the subject is W. T. Lhamon’s Raising Cain: Blackface Performance from Jim Crow to Hip Hop (2000). On African-American minstrelsy, see Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff’s Out of Sight : The Rise of African-American Popular Music (2009).