A Rare 1866 Obsolete Bank Note

The introduction of the ‘greenback’ in 1861 marked a turning point in the history of American currency. Greenback was the colloquial term for federal paper money issued during the Civil War, which consisted of both the Demand Notes of 1861 and the Legal Tender Issues that followed. Up until the 1860s, a patchwork of state-chartered banks and other entities were emitting a vast range of paper currency, much of it of dubious worth. This panoply of paper are now known as ‘Obsolete Bank Notes’ because they were superseded by federally issued currency as the government asserted control over the money supply during the 1860s. The creation of a common currency was part and parcel of the broader war effort, and the fact that it was backed not by specie, but only by the credibility of the United States government marked a momentous change.

As part of the federal government’s move to clean up the nation’s chaotic monetary situation, the wide range of existing bank notes in circulation needed to be dealt with. Senator John Sherman of Ohio led the charge against the confusing multitude of paper money in early 1863, calling for a tax on all notes not issued by the federal government and proposing much more rigorous regulation of banks. The resulting legislation passed in the form of the National Currency Act of 1863 (now known as the National Banking Act) on February 25. The act provided a framework for a new national banking system in which state banks had to apply for a charter from the federal government. If approved, the now “national” bank deposited funds with the Treasury Department and received some percentage of those funds back in the form of “National Bank Notes.” All of these new notes were of the same design, but entered circulation under the imprinteur of a particular bank. See, for example, this $2 note (known as a “Lazy Duece” for the horizontal 2), which was printed for the Mad River National Bank of Springfield, Ohio in 1865.

The new federal bank system had its advantages, and the accompanying effort to standardize American paper money proved popular with the public, but some banks were reluctant or not financially sound enough to become national banks. As a result, state bank notes continued to circulate, much to the chagrin of Senator Sherman, Secretary of the Treasury Samuel P. Chase, and other advocates of federal paper currency. It was not until 1865 that the legislation that spelled the end of what we now know as the Obsolete Bank Note Era was passed. It arrived in the form of a ten percent tax on any notes issued by state banks paid out after July 1, 1866. This particular tax is often erroneously credited to the “National Banking Act of 1865,” a piece of legislation that does not actually exist. The specific law was in fact part of the Internal Revenue Act of 1865, which you can find here. The law worked as intended as the looming penalty pushed state banks to either convert into National Banks and/or redeem their notes. Either route resulted in the withdrawal of the multitude of soon-to-be-taxed state bank notes from circulation.

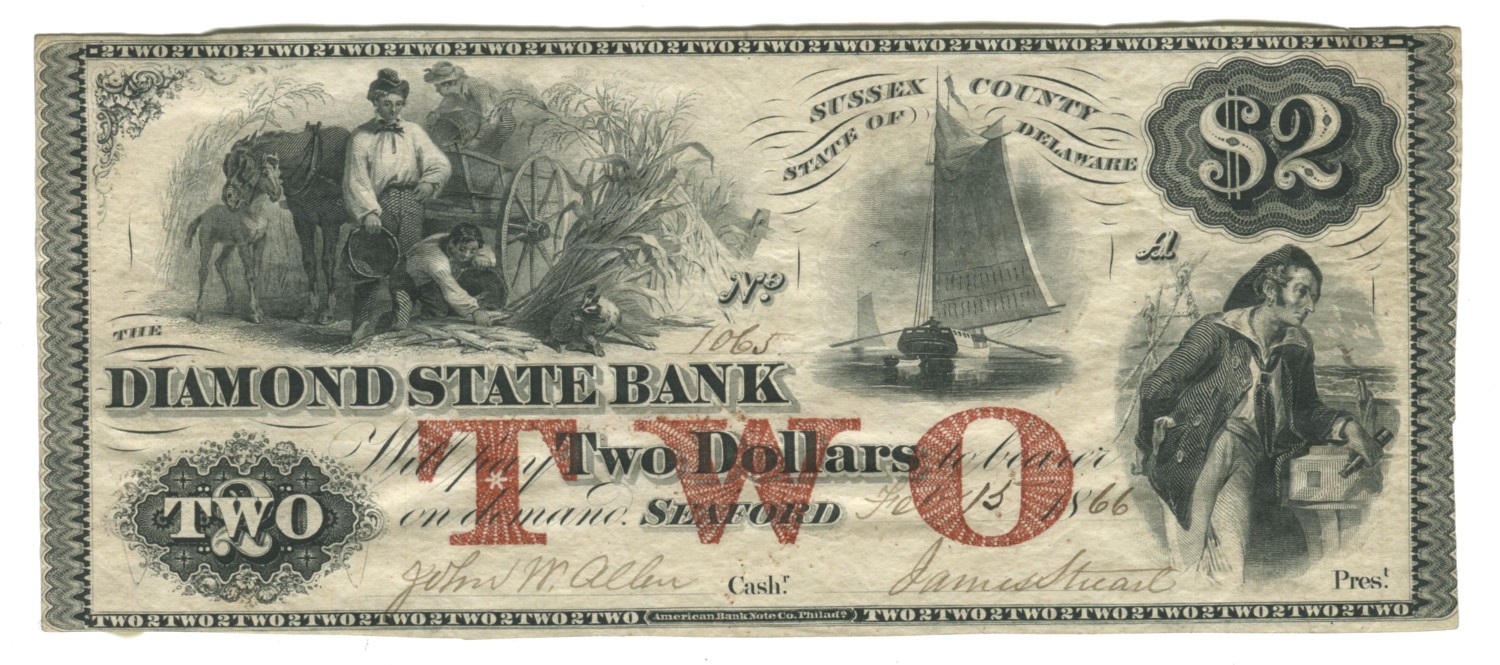

Among the final state bank notes issued was this attractive two-dollar note by the Diamond State Bank of Seaford, Delaware. It was printed by the American Bank Note Company and features some fine vignettes, wonderfully detailed counters, and a red tint plate. With a penned-in date of February 15, 1866, it is has the latest date of any of the obsolete note in the collection of the American Numismatic Society.

I suspect there’s more to the story of the Diamond State Bank than meets the eye. A report from a Pennsylvania newspaper in April 1866 shows that its notes were being rejected by banks in Philadelphia, so it does not seem to have been the most reliable institution. Whatever the case, this note seems to be one of the latest extant Obsolete Bank Notes, but perhaps our readers know of ones issued with later dates? If so, please let me know via email.