Early America

North America’s first European settlers often traded by barter, using corn, tobacco, and other goods as currency. During the 17th and 18th centuries, coins were often hard to come by in the British colonies, and royal authority was generally inattentive to the economic needs of its North American possessions. While Massachusetts did strike coins in the late 17th century, most of the money in circulation at the time of the Revolution was either Spanish or British. The pressing need for currency meant that people often used counterfeit coins or small-denomination private issues. Colonial governments also printed their own paper notes.

The Articles of Confederation that governed the relationship among the states allowed each one to issue its own coinage. Between 1776 and 1788, when the Constitution was ratified, both the states and the federal government produced coins, either as test patterns or for circulation. After 1788, the right to issue coins was reserved for the federal government, and the U.S. Mint finally began operation in 1792.

The early coinage of the independent United States is fascinating for what it says about the formation of the new nation, and coin design even drew the attention of the Founding Fathers. Benjamin Franklin designed a coin that exhorted Americans to “Mind Your Business,” which here means to keep one’s attention on one’s work. President George Washington rejected coins bearing his portrait on the grounds that they were tyrannical. Instead, U.S. coins first showed a personification of Liberty, and this word still appears on all new coins issued by the U.S. Mint.

Colonial America

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Britain fought with other European powers for territorial control of North America, but tended to neglect the economic needs of her colonies. In 1652, the Massachusetts Bay Colony began striking its own silver shillings. Unfortunately, the minimalist design allowed people to clip the edges for bullion and they were soon replaced by willow, oak and pine tree designs. British businessmen and some colonial governors also produced tokens and copper coins with royal permission. Many of these were rejected by colonists, who preferred Spanish silver.

Photo?

British tin token worth 1/24 real (1688) of James II (1685-1688) made for use in the “plantations,” as the American colonies were sometimes known.

1969.222.1460

Spanish bronze proclamation medal (1788-1808) from East Florida with the jasmine flower symbol of Florida between a lion and castle, representing Spanish Leon and Castile.

0000.999.71338

British copper St. Patrick farthing imported or use in New Jersey in 1681. These tokens were produced in London 40 years earlier, but were unpopular there.

1927.38.76

British silver 12 pence (1658-1659) from London for circulation in Maryland under Cecil Calvert (1609-1675), the second Lord Baltimore. The coin shows Lord Baltimore’s coat of arms.

1950.185.1

Massachusetts silver “pine tree” shilling (1652) marked “NE.”

1946.89.7

Massachusetts silver “pine tree” shilling (1667-1682). These shillings bear the date 1652, perhaps because it was that year that the crown had granted permission to strike coins.

1944.94.2

New York copper token marked “New Yorke in America,” depicting an eagle. These tokens were made for Frances Lovelace, New York’s governor from 1668 to 1673.

1952.159.1

British copper “Rosa Americana” 2 pence (1722) produced for the colonies by William Wood.

1931.58.407

The Continental Currency and State Coinage

In 1775, the Continental Congress, in rebellion against the British monarchy, introduced paper currency in an attempt to meet military expenditures. However, bullion that had been promised by France never appeared and the paper money was rapidly devalued.

After the revolution, many states introduced their own copper coins. These often borrowed elements from the British half penny of King George III (1760-1820), the most commonly used coins in the United States, but entirely new designs were also used.

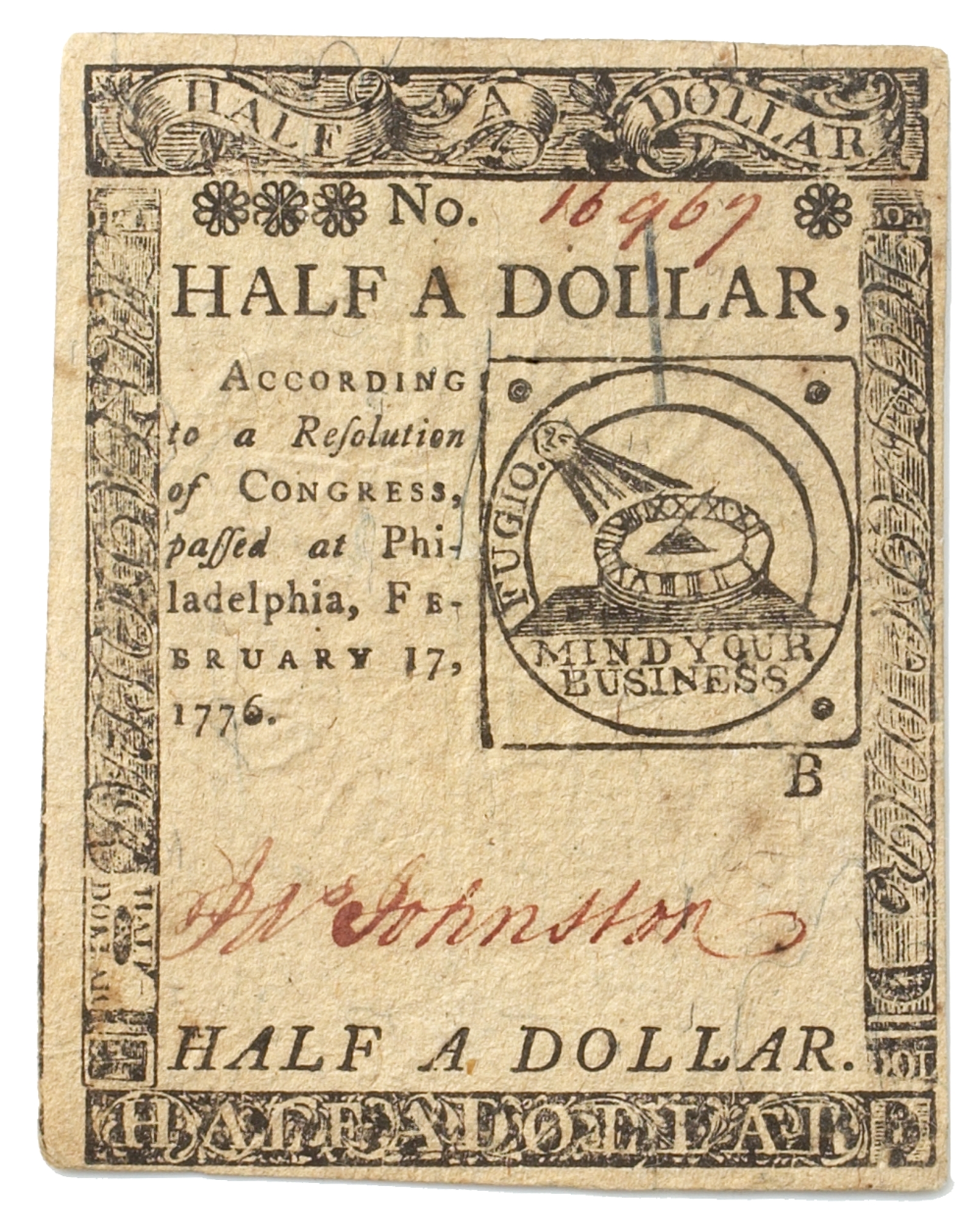

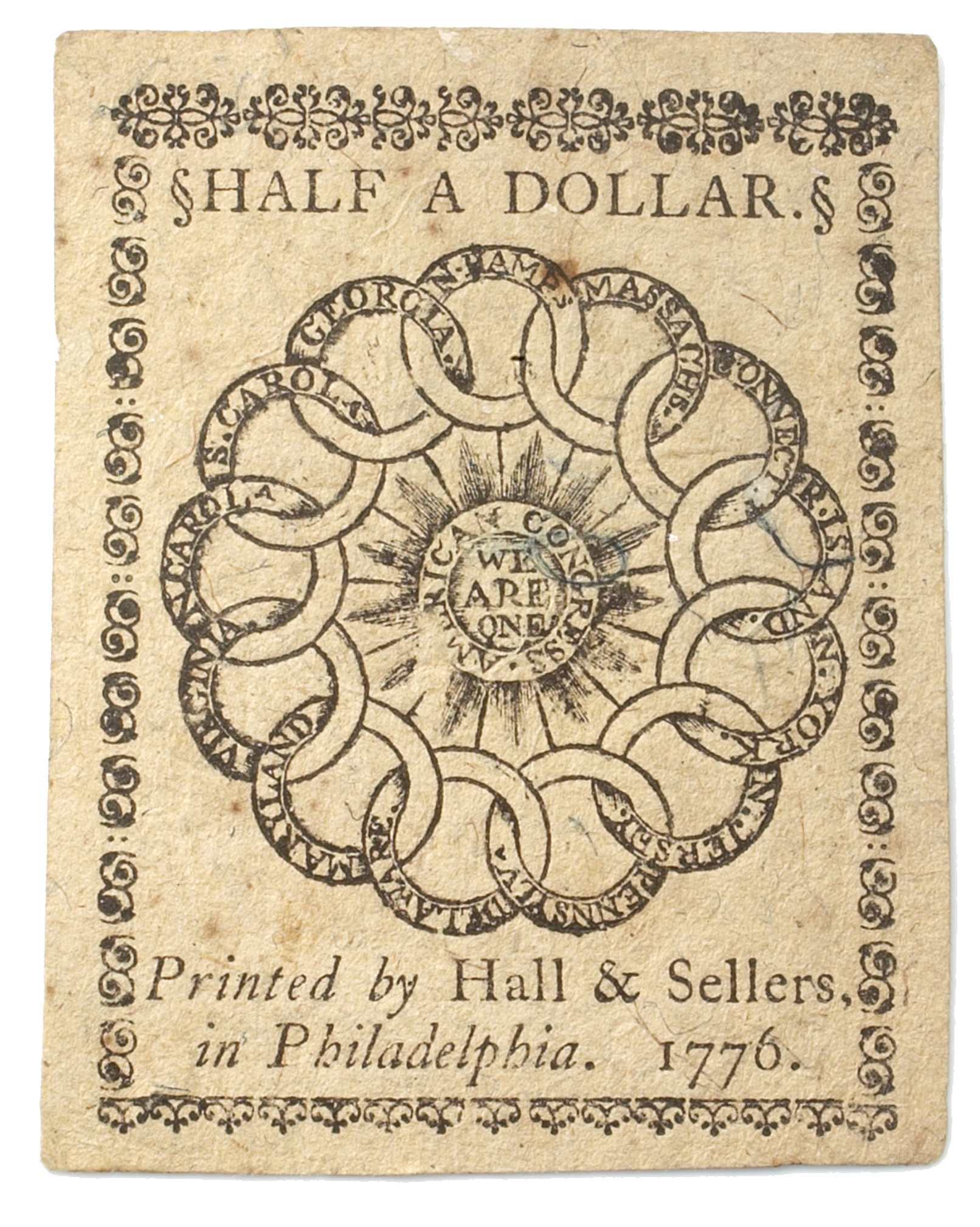

Continental Currency paper half dollar (1776) showing the 13 linked chains, one for each colony, and sundial motifs of Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790).

1974.103.3

Pewter Continental Currency pattern.

1911.85.7

British copper half penny (1770) of George III with the king’s portrait.

1940.113.119

British copper half penny (1774) of George III showing the personification of Britannia.

1949.65.44

New York copper cent (1787), using the Latin name for the state, Nova Eboraca. Although now independent, New York based this portrait on those of King George III.

0000.999.28466

Connecticut copper cent (1787) depicting Britannia as the personification of American Liberty. The legend translates as “Independence and Liberty.”

1931.58.489

Vermont copper cent (1785). Although an independent republic in 1785, Vermont became the 14th state in 1791.

1979.124.8

Massachusetts copper cent (1787) with the first usage of the denomination cent.

1943.9.31

New Jersey copper cent (1787) using the Latin name for the state, Nova Caesarea. This is the first coin to use the motto e pluribus unum (“out of many [states], one [country]”).

1945.42.688

Experiments of the Confederation Period

In addition to the state coinages, in the 1780s, several new Federal designs for copper cents were issued. Because there were no laws against the private production of coinage, silver and goldsmiths like John Bailey, Ephraim Brasher and John Chalmers also struck coins for their native cities and states.

U.S. copper “Nova Constellatio” cent (1785) depicting 13 stars, representing the original Thirteen Colonies, as a new constellation around the eye of Divine Providence.

1941.131.1005

U.S. copper “Confederatio” cent (1785), depicting the personification of America trampling a crown. The inscription translates as “America, the enemy of Tyrants.”

1941.147.3

U.S. copper “Immune Columbia” cent pattern (1785). The seated Britannia copied from British coins is modified with the scales of justice and the legend “Immune Columbia,” signifying the freedom of the new nation.

0000.999.28547

U.S. copper “Fugio” cent (1787) authorized by Congress, reusing the sundial and linked chain designs of the Continental Currency.

1949.136.9

New York copper “Excelsior” cent (1787) depicting the state seal. It is believed to have been made by John Bailey, the partner of the famous New York goldsmith Ephraim Brasher (see Case 18).

1899.25.1

Annapolis silver shilling (1783) privately produced by John Chalmers.

1941.149.8

George Washington

Although a number of patterns for U.S. coins were made with his portrait, George Washington disapproved of this practice as a sign of tyrannical rule. It has been suggested that, after his 1791 portrait designs were rejected, John Gregory Hancock Sr. (1775-1815) privately produced the “Roman Head” cent in which Washington is made to look like a despotic Roman Emperor.

U.S. copper “Large Eagle” cent pattern (1791) by Hancock Sr.

0000.999.28515

U.S. copper “Roman Head”cent pattern (1792) by Hancock Sr.

1951.192.1

Bronze “Washington before Boston” medal (1786) produced in Paris for Congress to commemorate the British evacuation of Boston (1776).

1940.100.366

Coin Patterns of 1792

When Congress officially established the U.S. Mint in 1792, engravers with varying degrees of skill submitted new designs for American coinage. The patterns shown here were never produced as circulating coins.

U.S. pewter quarter dollar pattern by Joseph Wright, depicting Liberty.

1980.66.2

U.S. copper cent pattern by William R. Birch, designed to have a silver plug added to bring the metal value up to 1 cent.

1956.163.25

U.S. silver half dime pattern probably by William R. Birch, depicting Liberty. The inscription translates as “Liberty: Parent of Science and Industry.”

1932.51.38

Early U.S. Cents

The design of early U.S. cents was heavily influenced by the iconography of Liberty developed by the French artist Augustin Dupré for the “Libertas Americana” medal of 1782. George Washington, who owned one of these medals, may have suggested its use as a model for U.S. coinage. Franklin’s linked chain motif also continued to be used.

Bronze “Libertas Americana” medal (1782) by Augustin Dupré.

0000.999.38369

Copper cent (1793).

1946.143.4

Copper half cent (1795).

1906.99.4

Early U.S. Silver and Gold

The fledgling U.S. mint had difficulty producing large quantities of precious-metal coinages. In 1794, only 1,758 silver dollars were issued. In the first year (1795) that the mint issued gold 10 dollar pieces (officially known as “eagles”), it could only produce 5,583.

Silver half dime (1795) depicting an eagle. Because of the poor design, it was replaced in 1796.

1931.109.2

Silver dollar (1794) depicting Liberty.

1965.97.1

Gold 10 dollar piece (1795) depicting an eagle.

1908.93.60

Gold 2 1/2 dollar piece (1796) depicting capped Liberty.

1980.109.2098

Exhibition Parts

I. Ancient Greece and the Mediterranean World

III. Medieval Byzantine and Islamic Empires

V. Ancient and Medieval East and South Asia

VI. New Sources: The 15th and 16th Centuries

VII. Europe in Transformation: The 17th Century

VIII. The Enlightenment: The 18th Century

XI. East and South Asia in the 19th Century

XII. Empires and Colonialism in the 19th Century

XIII. Moving West: 19th-Century America

XV. The United States in the 20th Century