The far-reaching historical implications of the late Roman and Byzantine gold coinage, from the fifth century through the eighth, have made this period the focus of a great deal of research in recent decades. A great wealth of material awaits collection and interpretation, and it is not yet possible to produce a synthetic monograph on all aspects of the subject. This volume brings together contributions on various topics in the hope of demonstrating how current progress has been made possible by new or refined methods as well as by the evidence of new finds. The following introductory remarks are intended to provide a summary of the current state of scholarship and a rough sketch of the problems that remain to be solved.

Numismatic considerations, which are closely related to the political history of the period, define the termini of this volume. The permanent division of the empire between Arcadius and Honorius was reflected by different developments in the coinages of the East and the West. Various attempts to assimilate the western half of the empire during the sixth and seventh centuries all failed in the end, but they provide a fertile field for the study of monetary politics. By the end of the eighth century the empire had lost most of its western dependencies—notably the African and Italian exarchates—and with those losses provincial mints virtually ceased to exist.

These centuries have fared unevenly at the hands of numismatists. The period of Anastasius I, in modern times regarded as the beginning of the Byzantine coinage proper, has recently drawn the attention of several scholars, but the fifth century has been poorly served by modern studies, especially as the framework that could be provided by RIC 10 is still lacking. The old studies of Sabatier for the East and Cohen for the West lack photographic documentation and are in any case inadequate, since coins of the eastern and western emperors are listed separately and without regard to the mints that produced them.1 Eastern and western coins are confused, and those of the empresses are ascribed to their husband, with the consequence that (for example) the eastern issues of Galla Placidia and the western ones of Pulcheria are concealed, as is the entire system of mutual recognition pieces so characteristic of fifth century coinage. The distribution of issues of empresses who struck under more than one ruler has also been obscured.2

Tolstoi's work on the eastern emperors is written in much the same tradition and presents a wealth of material, but is confined mainly to coins in his own collection and that in the Hermitage with additional references to Sabatier. For the West Robertson's recent catalogue of a much more limited collection unfortunately follows the same princple.3 Hahn has dealt with the eastern gold and silver coinage of the reign of Theodosius II, and a similar study covering the period through the death of Zeno is in preparation; but for the West the work of Ulrich-Bana stands as a solitary milestone in a field otherwise tilled by amateurs.4

The most urgent desideratum remains the continued accumulation of numismatic material to permit the most detailed possible study of the coinage. The systematic listing of hoards and stray finds will provide a reliable picture of monetary circulation and should confirm mint attributions based on stylistic criteria. Sorting out the attributions of gold coins not distinguished by specific mint marks and allocating them to different mints will yield the outlines of monetary administration.

Moreover, though the studies of W. E. Metcalf, C. Morrisson, and D. M. Metcalf below are virtually unparalleled in the Byzantine series, the compilation of similar die studies for other mints will permit insight into their activities and provide at least a relative idea of output, which is perhaps the most important question for economic historians.

The connection between civil, fiscal, and monetary administration has been set out by J. P. C. Kent and Hendy.5 As we now have a good idea where and when to look for gold mints, the possible attributions have been considerably reduced and are more securely based. The guiding principle is the division of the gold coinage into the regular production of the four praetorian prefectures (Orien, Illyricum, Africa, and Italy) plus some extraordinary cases (the Crimea, Spain, and Sicily) in which the existence of a gold mint is at least a possibility. Under special conditions military mints seem to have been active temporarily in the East during the troubled first quarter of the seventh century.

The overwhelming preponderance of gold coinage was stuck in and for the eastern prefecture, where the metropolitan moneta auri operated continuously with a number of officinae; usually ten were charged with the production of solidi, the main denomination. One must suppose that fractions and ceremonial pieces (in gold and silver) were struck in a single officina, which did not need to mark its coins, although it is uncertain whether this officina (or these officinae, if each denomination came from a separate workshop) is to be identified with one of the ten solidus officinae or is in addition to them. During the fifth and (rarely) the seventh centuries a portion of the Constantinopolitan solidi, in many types, lack an officina number. These unmarked pieces may have been struck at the beginning of every issue, since they are relatively much more numerous in short issues than in longer ones.6 Perhaps this is to be explained on the assumption that special orders were given for the striking of distribution pieces, outside the normal quotas of the officinae, on the occasion of accessions or anniversaries or for other ceremonial purposes connected with the introduction of new types.

Several explanations have been proposed for cases in which solidi of Constantinopolitan fabric display officina numbers higher than ten. In the seventh century the additional letter was probably an issue mark.7 In the rare cases of sixth century solidi with higher numbers, other interpretations may be required: additional officinae detached for use in other regions,8 indictional dates,9 cooperation between two officinae, or reference to a special weight standad.10

Where secret or issue marks are involved, their proper purpose is debatable. Possible explanations include marking of an extraordinary issue with a numeral indicating its date, amount, or occasion, a special destination ordered by one or another department of the state for distribution purposes, or a special metal source. The mark ⊖ is especially frequent.11 It should be noted that the occurrence of these secret marks suddenly increases under Heraclius, when the government had to resort to loans. Dates were twice introduced to the regular solidi of Constantinople, then abandoned: 567/8 and 635-50; while a temporary preponderance of the fifth and tenth officinae over the others (especially around 610) is explained by C. Morrisson, who postulates the connection of different officinae with certain state departments.12 The high standard of weight and fineness (97 to 99 percent) was maintained in Constantinople throughout the period with only a minor decline under Constans II and Constantine IV.13

Stylistically, the Constantinopolitan gold coins display great uniformity: doubtless there were several die engravers working simultaneously with shared punches. This often makes comparison of obverse dies very difficult.14 A broader range of style can be observed when a single type is struck in large quantity or over a long period;15 this is due to changes over the course of time rather than to the existence of different eastern mints. Under normal circumstances there were no mints other than Constantinople in the eastern prefecture. The fanciful attributions of D. Ricotti Prina (Nicomedia, Cyzicus, Antioch)16 are untenable, and the acceptance of Grierson's incorrect attributions of sixth-century solidi to Antioch is unforunate.17

A more serious candidate for a gold coinage in the East is Alexandria, capital of the diocese of Egypt, which had long been isolated economically from the empire and which had its own system of local copper coinage. The irregular use of AΛᵻOB on solidi of Justin II of Constantinopolitan fabric reveals a temporary gold production with dies provided by Constantinople. Although the signature was corrected to the prescribed universal mark for gold, CONOB, production seems to have lasted for some years, since it had to be sustained by locally cut dies of distinct style. These Alexandrian solidi of Justin II, which were differentiated from Constantinopolitan issues by other secret marks, might be connected with the presence of the emperor's nephew Justin as augustalis of Egypt in 566. A similar situation, with a member of the imperial family being in charge of Egypt, occurred under Heraclius, when his cousin Nicetas had to fight the Persians and may have been short of money (616-18).18 The issue of solidi from Alexandria during the revolt of Heraclius (608-10), as proposed by Grierson, is less secure.19

There are two other groups of questionable attribution. One is of Carthaginian style and may belong to the special large-module series there (see below).20 The other shows the peculiar style of an itinerant military mint which also produced copper coins with mint marks, first of Alexandria, then of Cyprus. As Cyprus was the proper base for military campaigns in the eastern Mediterranean basin, it is plausible that it was the home of an extraordinary gold mint to meet military needs.21 The activity of this mint began under Phocas22 and continued with the unusual consular solidi of the two Heraclii, which were supplemented by fractional issues in the name of the deceased emperor Maurice Tiberius. The solidi are marked with immobilized indictional or regnal dates or by a sequence of the letters I, IX, or IΠ, which may refer to a lustral cycle.

After Heraclius' coronation there were further issues, apparently for his Persian campaigns. Their attribution to Cyprus and their dating (up into the 620s) are not universally accepted and other suggestions, such as Alexandria or Jerusalem (from which we know copper coins from the siege of 614) have been made.23 The evidence of provenance is of little help because the finds, which range from Egypt to Turkey, correlate with the extended theater of war.

| 5 |

J. P. C. Kent, "Gold Coinage in the Later Roman Empire," Essays Mattingly, pp. 190-204;

M. F. Hendy, pp. 129-54. See also the latter's important new Studies in the Byzantine

Monetary Economy, c. 300-1450 (Cambridge, 1986), particularly pp.

386-423.

|

| 6 |

See Hahn (above, n. 4), p. 106.

|

| 7 |

MIB 3, pp. 84-85.

|

| 8 |

Following J. Lafaurie, "Un Solidus in�dit de Justinien I frapp� en Afrique," RN 1962, pp.

167-82. W. Hahn (MIB, p. 51) suggested Justinian I for Carthage, but this is refuted by

C. Morrisson, below, p. 52.

|

| 9 |

N. Fairhead and W. Hahn, below, pp. 33-38.

|

| 10 |

See MIB 1, p. 50, n. 20, for light weight solidi from Justinian I to Maurice.

|

| 11 |

Date: MIB 2, p. 32 for Justin II; amount: p. 61 for Maurice;

occasion: N for nalalis [dies imperii], p. 61; special distribution: P.

Grierson, "Solidi of Phocas and Heraclius: The Chronological Framework" NC 1959, p. 137. With respect to

the θ, a reference to a treasury (thesauros) is tempting (MIB 3, p. 129, and Hendy, "Studies" [above, n. 5], pp. 411-12, n. 169) but does not fit in all cases.

|

| 12 |

MIB 2, p. 32, for the earlier dates; for the later dates, MIB 3, pp. 86 and 124, and C. Morrisson,"Le trésor byzantin de Nikerta," RBN 118 (1972), pp. 29-91.

|

| 13 |

Weight and fineness: C. Morrisson, "L'or monnay� de Rome × Byzance," Comptes-rendus Acad.

Inscr. 1982, pp. 203-23; decline: C. Morrisson (above, n. 12), pp. 54-55.

|

| 14 |

Occasionally, however, obverse die links have indicated that a reverse die may have moved from one officina to another. See

P. Grierson, Coins mon�taires et officines × l'�poque du bas-empire," SM 11 (1961), pp. 1-8;

C. Morrisson (above, n. 13), pp. 39-40; W. E. Metcalf, below, p. 25.

|

| 15 | |

| 16 |

D. Ricotti Prina, La monetazione aurea delle zecche minore bizantine . . . (Rome, 1972).

|

| 17 |

See DOC 1, p. 133. Grierson now prefers Thessalonica: see Coins, p.

53.

|

| 18 |

MIB 2, pp. 45-46, for Justin; MIB 3, p. 95, for Nicetas. The

Alexandrian origin of the Justin II solidi was recently doubted by Hendy, Studies (above, n. 5), p. 404, who was not aware of the Egyptian hoard evidence.

|

| 19 |

DOC 2, p. 207.

|

| 20 |

MIB 3, p. 79.

|

| 21 |

MIB 2, pp. 85-86, and MIB 3, p. 89.

|

| 22 |

MIB 2, p. 97.

|

The second praetorian prefecture, Illyricum, had its small gold mint at Thessalonica. Little can be added to D. M. Metcalf's study in this volume except the hope that uncertainties regarding the fractions and the possible issues of Phocas will be elucidated by further discoveries.24 The fact that the output of this mint is estimated to be small raises the question of the extent to which it was designed to meet the needs of the whole prefecture or whether it had only to serve a small civilian department at Thessalonica (perhaps the idike trapeza of the area praefectoria).25 It is also pertinent to observe that dies provided by Constantinopolitan mint engravers were used from time to time; on the other hand, the mint showed relative independence in maintaining elements of older, out-of-date typology at least until 562, when it was brought into line at the same time that the local copper currency system was abolished.

The beginnings of gold coinage in the African prefecture from its creation in 534 to 578 are dealt with here by Morrisson. Before the Justinianic reconquest Carthage had never struck gold coins.26 It seems that the Vandals possessed enough gold emanating from imperial mints that they could afford to respect the gold prerogative of the emperors. The new Carthaginian gold mint was virtually a solidus mint, from which we know only a few fractional issues, struck for ceremonial purposes, from the time of Heraclius onwards. The coins were normally dated by indictional years and sometimes by regnal years as well (under Tiberius II and Maurice). It is now clear that the numerals on the early solidi of Justinian I are dates, not officina designations. The continuous dating enables us to follow the curve of the output: its fluctuation, as Morrisson has recently shown, can be connected with lustral taxation.27 Technical considerations now explain the puzzling tendency to a globular fabric from the end of the sixth century on: it obviated the need for hammering the blanks and speeded the process of striking, for less effort was required when smaller blanks were used.28 The globular solidi are, however, accompanied by limited issues on larger flans, and their deviation from the usual pattern and their accompaniment by rare fractions demonstrate their special ceremonial character.

It can easily be supposed that the strange looking globular solidi would not easily have entered the circulating medium outside Africa, and in fact the evidence for external finds is scanty.29 The African hoards have been carefully recorded by Morrisson, and to some extent these can be connected with historical events. Especially for the last years of Byzantine domination, the coins provide new evidence: they even pinpoint the date of the first Arab conquest of Carthage at the very end of 695.30 The splitting-off of the Sardinian branch mint antedates this event,31 but the circumstances remain uncertain.32 Another study by Morrisson has shown that there was a slight decrease in the weight of the African gold coins under Constans II (642-68), but that the high fineness was retained until the end.33

| 23 |

For Alexandria, DOC 2, p. 32; for Jerusalem, see Grierson, Coins,

p. 93, and Hendy, pp. 415-16. Hendy presumes a transfer of the staff of the Antiochene

mint by Phocas' general Bonosus in 608; the style of the portraiture, however, shows no resemblance to the copper of Phocas

from Antioch or that of Heraclius from Jerusalem.

|

| 24 |

S. Bendall, "A New Mint for Phocas," NCirc 92 (1984), pp. 256-57, has assigned to

Thessalonica under Phocas several tremisses hitherto given to Sicily. There remains the difficulty of the contrast with Thessalonican

issues of Maurice and with the Thessalonican copper of Phocas himself. Heraclius' solidus MIB

2 should probably be added to Thessalonica. The tremisses of Justinian I

almost certainly have to be augmented by specimens of a fabric like MIB 191 as can be seen from

comparison with the drawings of the imperial bust and diadem/hair styles on Thessalonican copper, D. M. Metcalf,

The Copper Coinage of Thessalonica under Justinan I (Vienna, 1976), p. 22, 3a, and p. 24, 4d. To this group belong the following specimens: BMC Vandals, pl. 16,

16, 1.47; DOC 19.1, 1.49; Mechitarist coll., Vienna = MIB 191; Rauch 36, 20-22 Jan. 1986 = Hahn coll., 1.48; Frankfurter Münzhandlung 90, 2 Mar. 1943,

28; Kress 112, 22 June 1959, 969; Hirsch 68, 1-3 July 1970, 916; Ciani and Vinchon, 6-7 May 1955, 514, 1.51.

|

| 25 |

For the subdivisions of the area praefectoria, see J. Karayannopoulos, Das Finanzwesen des

fr�hbyzantinischen Staates, S�dosteurop�ische Arbeiten 52 (Munich, 1958), pp.

80-84, and Hendy (above, n. 5), pp. 411-12. J. M. Carrie, Collection

de l'école Française de Rome 77 (1986), p. 129, has advanced the idea that the Thessalonican moneta auri was

active only in order to check the weight of the solidi paid to the treasury and to recoin the light ones; but, in fact, Thessalonican

solidi tend to be somewhat lighter in weight.

|

| 26 |

See P. Grierson, Münzen des Mittelatters, trans. A. P. Zeller

(Munich, 1976), p. 16, illus. 2-3, his supposed Vandalic solidus from Sardinia is very

doubtful. See also C. Morrisson, "La Circulation de la monnaie d'or en Afrique a l'epoque vandale, bilan des

trouvailles locales," M�langes de numismatique offerts × Pierre Bastien..., ed. M. Huvelin

et al. (Wetteren, 1987), pp. 325-44.

|

The gold of the adjacent Italian prefecture has other antecedents. The old central mint of Rome retained its role as an institution of the regular administration from the time of the western empire through the Ostrogothic dominion and into early Byzantine times. The court mint of Mediolanum, first opened as a moneta comitativa or traveling mint, had been moved to heavily fortified Ravenna in 402. Aetius reactivated the Milan mint in ca. 450 for military purposes. Thus the magistri militum of the western empire had their own money supply during the second half of the fifth century. It was only here that Odoacer could maintain a continued coinage in the name of the last western emperor, Julius Nepos, whom Zeno demanded that he recognize in 476.34

Theodoric closed the Milan mint in the late 490s, perhaps as a result of his treaty with Anastasius I, in which imperial prerogatives were newly defined.35 The same fate befell Ravenna, a demonstration that the western court had ceased to exist. A typological caesura in the Italian gold marks a new stage in the gradual assimilation to Constantinople under Theodoric.36 The distribution of fifth-century solidi among the three Italian mints (and a fourth at Arelate) is fairly clear-cut, since most of them bear mint marks, but that of the unsigned fractions is more problematic. Only the Milanese tremisses display a distinctive style.37 The differentiation between Rome and Ravenna must rest on a close comparison of dies with those of the mint marked silver pieces of small module. The lack of a monograph in this field is keenly felt. The reconstruction of the framework of the fifth-century gold issues of Italy will provide important insights into the relationship between the eastern and western courts, inasmuch as the western mints struck a certain number of coins in the name of the eastern emperor at times of mutual recognition.

From about 500 onward the mint of Rome was the only Italian moneta auri until Justinian's Gothic war once more involved Ravenna. While the Ostrogothic kings had to move their mint first to Ravenna (536-40) and then to Ticinum (540-52), the Byzantines reorganized the Rome mint in the newly installed Italian prefecture, dividing it into ten officinae. This corresponds with the Constantinopolitan model.38 The mint soon followed the praetorian prefect to Ravenna as a consequence of the second siege of Rome (545/6). The distinction between the Roman and the early Ravennate solidus issues is problematic. Although the Roman pieces under Byzantine auspices started out with a clearly cut star of six rays—differentiating them from the eastern solidi, which are marked with a star of eight rays—this characteristic disappears later in Ravenna. Again the comparison with the mint marked copper provides a guide. As activity decreased during the later part of Justinian's reign, the indication of officinae became meaning less, and the letters in question seem to have become dates. The date at which this occurred and what kind of dating was employed are still under discussion.39 Even less is understood in the case of Tiberius II, when the western authorities could not decide whether to count his years as Caesar or his years as Augustus.

The contemporary gold coinage of the last three Ostrogothic kings—Hildebad, Totila/Baduila, and Theia—served mainly to pay their Frankish auxiliaries, and therefore evoked Frankish imitations which are not always easily recognizable as such. In the last third of the sixth century the Ravenna attributions need to be purged of similar coins which should be given to Sicily (see below). There are further difficulties in sorting out the early Lombard imitations which also use the Ravenna model. In addition to the royal mint in Ticinum, several smaller workshops of varying quality operated in the centers of the duchies.40

Rome's resumption of the striking of gold seems to coincide with Ravenna's growing isolation. The attributions in the earlier period (from Tiberius II to Heraclius) have hitherto been very hypothetical,41 but from Constans II onward they become more coherent: at this time Rome's issues begin to exceed those of Ravenna in quantity. From Constans II to Justinian II they show small monograms which probably refer to church treasuries or to a magistrate who had something to do with coinage.42 In any case there is no connection with the papal monograms which made their appearance on the small silver coins of Rome from the pontificate of Constantine (708-15) onward.43

In the last three decades of the seventh century a third Italian gold mint emerges at the seat of the Neapolitan dukes. Among a group of more or less imitative coins, its products are at first difficult to identify, but they become intelligible as soon as we can trace a sequence of issues on which style and administrative marks can be seen to correlate.44

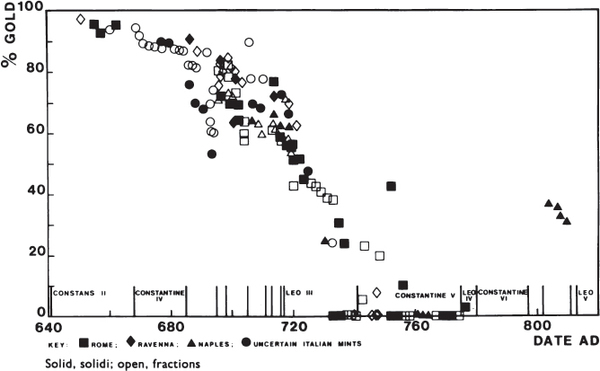

In the eighth century the characteristic feature of the Italian coinage is its visible decline in weight and fineness. This has attracted the application of newly developed or refined methods of metallurgical investigation: see the contribution of Oddy to this volume. In general a short age of gold in the Mediterranean world accounts for its limited striking. The fluctuations in the gold content of the Rome coins, which resulted in a temporary token coinage of copper solidi, are extremely puzzling. These coins can be dated precisely on the basis of a continuous sequence of indictional years.45 The end of this old currency came with the Carolingian reform in Italy and with it the end of Byzantine hegemony over Rome. The latest Byzantine issue of copper solidi, as recognized by R. Denk,46 dates from 777/8. The end of gold coinage in Ravenna had come a little earlier. After the Lombard conquest of the city in 751, King Aistwulf continued to strike there in the exarch's mint,47 but under Frankish pressure he lost the city to the Popes and with the departure of the court there was no longer any need to maintain a gold mint. The differentiation between Rome, Ravenna and Naples under Leo III and Constantine V is less difficult, because the very distinct style of Rome is also seen on the small silver coins with papal monograms mentioned above, and also because a mint signature is occasionally used. On the other hand we can observe affinities between coins of Naples and those of Beneventum, where the Lombard dukes are found striking coins with ducal monograms from about 705 onward.48 Naples is the only Byzantine mint in Italy where a limited production has to be reckoned with after 800.49 The remnants of Byzantine territory in southern Italy were by now provided with coinage from Syracuse.

Having dealt with the gold mints under regular administration, there remain attributions to possible mints with special status. Three localities are considered: the Crimea (Cherson), Spain (Cartagena), and Sicily (Syracuse). Of these only the Spanish and the later Sicilian attributions (after 640) are secure; the Chersonese and the earlier Sicilian attributions are affected by various uncertainties.

| 27 |

C. Morrisson, "Estimation du volume des solidi de Tib�re et Maurice × Carthage," PACT 5

(1981), pp. 267-84.

|

| 28 |

For hammering, MIB 3, p. 91. For smaller blanks, see F. Delamare, P.

Montmitonnet, and C. Morrisson, "A Mechanical Analysis of Coin Striking: Its Application to the

Evolution of Byzantine Gold Solidi Minted in Constantinople and Carthage," Journal of Mechanical Working Technology

10 (1986), pp. 253-71.

|

| 29 |

There are only a few intruders in later Sicilian hoards, at a time when Sicilian gold coins were struck on flans of similar

shape.

|

| 30 |

For the sixth century, see C. Morrisson, "Le trésor byzantin de Souassi," BSFN 37 (1982),

pp. 214-15, and her contribution in this volume; for the seventh, R. Guery, C.

Morrisson, and H. Slim, Rougga, le trésor de monnaies d'or byzantines (Rome, 1982), p. 71. For the last issue see MIB 3, p. 167.

|

| 31 |

MIB 3, p. 167.

|

| 32 |

C. Morrisson, "Un trésor de solidi de Constantin IV de Carthage," RN 1980, p. 159;

contrast MIB 3, p. 153.

|

| 33 |

C. Morrisson, J. Barrandon, and P. Poirier, "Nouvelles

recherches sur l'histoire mon�taire byzantine: �volution compar�e de la monnaie d'or × Constantinople et dans les provinces

d'Afrique et de

Sicile," J�B 33 (1983), pp. 267-86, esp. pp. 274-75.

|

| 34 |

J. P. C. Kent, "Julius Nepos and the Fall of the Western Empire," Corolla memoriae E. Swoboda

dedicata (Graz, 1966), pp. 146-50, and W. Hahn, "Die letzten Jahre der

Mediolanenser Münzpr�gung vor der Schliessung der Münzst�tte durch Theoderich," G. Gorini, ed., La zecca di Milano. Atti del convegno internazionale di studio Milano 9-14 maggio 1983 (Milan, 1984), pp. 229-40.

|

| 35 |

MIB 3, p. 56, and Hahn (above, n. 34), p. 235.

|

| 36 |

MIB 1, pp. 77-78.

|

| 37 |

For documentation, see O. Ulrich-Bana, Moneta Mediolanensis 352-498 (Venice, 1949) and W. Hahn, "Die Münzst�tte Rom unter den Kaisern Julius

Nepos, Zeno, Romulus Augustus und Basiliscus (474-91)," RIN (forthcoming).

|

| 38 |

MIB 1, pp. 53-54.

|

| 39 |

MIB 3, pp. 66-67, and the contribution by N. Fairhead and W.

Hahn in this volume.

|

| 40 |

For Ticinum see E. Bernareggi, Il sistema economico e la monetazione dei Longobardi nell'Italia

superiore (Milan, 1960); comparative material for the unattributed pieces is

assembled in MIB 3, pl. 55. See also P. Grierson and M.

Blackburn, Medieval Coinage, vol. 1 (Cambridge, Eng., 1986), pp. 55-66.

|

| 41 |

W. Hahn, "More about the Minor Byzantine Gold Mints from Tiberius II to Heraclius," NCirc

87 (1979), pp. 552-55.

|

| 42 |

MIB 3, pp. 131 and 154.

|

| 43 |

See M. D. O'Hara and I. Vecchi, "A Find of Byzantine Silver from the Mint of Rome for

the Period A. D. 641-752," SNR 64 (1985), pp. 105-40.

|

Cherson, a trading outpost under Byzantine hegemony, had long retained some sort of autonomy, as is documented by its anomalous copper coinage. Under Heraclius and Constans II a few solidi of eastern appearance, but differing from the Constantinopolitan fabric and marked by the sign X, have been given tentatively to Cherson.50 The lack of find evidence for them is hardly surprising since almost no gold coins have been recorded as found in the Crimean peninsula.51 Six corresponding issues are attested by single specimens;52 it seems that most of them were dated, although the elucidation of these dates is somewhat problematical.

| 44 |

MIB 3, pp. 155 and 169-70; M. D. O'Hara, "A Curious and Interesting Solidus for the Mint

of Naples under Justinian II," NCirc 96 (1988), pp. 43-44.

|

| 45 |

DOC 3, pp. 87-88.

|

| 46 |

R. Denk, "Zur Datierung der letzten byzantinischen Münzserien aus Rom," LNV 1 (1979), pp.

139-43.

|

| 47 |

See P. Grierson (above, n. 26), p. 46, and above (n. 40), p. 65.

|

| 48 |

MIB 3, p. 188. For this series see also W. A. Oddy, "Anaysis of the Gold Coinage of

Beneventum," NC 1974, pp. 74-109, and P. Grierson and M.

Blackburn (above, n. 40), pp. 66-72.

|

| 49 |

DOC, 3, pp. 84-85.

|

| 50 |

W. Hahn, "The Numismatic History of Cherson in Early Byzantine Times: A Survey," NCirc 86

(1978), pp. 414-15, 471-72, 521-23. The Russian specialists in the coinage of Cherson have not discussed the attribution of

this solidus,

but see I. V. Sokolova, Moneti i petshati vizantijskogo Chersonesa [Coins and seals of

Byzantine Cherson] (Leningrad, 1983), p. 28.

|

At the opposite end of the Byzantine world, in the West, there was a military district on the Spanish coast which was loosely attached to the African prefecture. Since this had been Visigothic territory and was surrounded by the Visigothic kingdom, where the tremissis was the only denomination struck, a need for this denomination had to be met. Carthage did not supply them, since it was not a tremissis mint, and was in any case remote. They were therefore manufactured locally from the beginning of the Byzantine presence under Justinian I (554) to its end under Heraclius (615-24). They have a pronounced and peculiar style with reminiscences of Visigothic coins in their lettering and even occasional typological borrowings. The evidence of provenance makes their attribution even more secure. Since the group was first identified by Grierson,53 the whole sequence of emperors from Justinian I to Heraclius is illustrated by a handful of specimens. Those of Justin II and Tiberius II have been discovered only recently.54

By far the most important extraordinary gold mint was that of Sicily, which became the second most active mint in the empire from the later seventh century onward. Until recently not only its beginnings but the entire first hundred years of its supposed existence were more or less obscure. The spectacular Monte Judica hoard, presented in this volume, has shed new light on the early period of Sicilian gold coinage. The position of this island had always been of exceptional importance, so it is hardly surprising to find that for a long time it was not subject to the regular administration but was more directly controlled from Constantinople. Whenever the money supply from the capital was insufficient or its maintenance was considered inadvisable, a local mint had to serve as a substitute. Its products were not, at first, intended to reveal their non-Constantinopolitan origin, and we have the same difficulties contemporaries must have had in distinguishing them. This is, incidentally, also partially true of sixth-century copper from Sicily. Constantinopolitan as well as Ravennate stylistic influences hinder the attributions. While the attribution of Sicilian solidi now seems secure throughout (with minor exceptions under Heraclius),55 the fractions offer serious problems from Maurice into the first half of Heraclius' reign. A distinct group of them, which has been given tentatively to Sicily before 610, has recently been moved to Thessalonica without satisfactorily solving all the problems connected with this transfer.56

The Sicilian style proper and the use of specific administrative marks begins late in the reign of Heraclius. Occasional dating occurs under Heraclius and Justinian II.57 The effect of the temporary stay of Constans II in Syracuse (663-68) on Sicilian coin production is still a matter of dispute: it is connected with the question of a traveling field mint accompanying the emperor and with the supposed coinage of the usurper Mezezius in Sicily, the authenticity of which has been contested.58 The weight was reduced by Justinian II in his first reign (685-95) and again under Philippicus (711-13) following the western tendency toward lower weight standards.59 The fineness fell during the reign of Leontius (695-98) and after, but after some fluctuation it was stabilized by Leo III in the 730s at a level about 15 percent lower than in Constantinople.60 When the Arabs began their piecemeal occupation of the island (a process which extended from 827 to 878) and the Byzantine presence there became more and more isolated, a final debasement in weight and fineness began which led to coins consisting of one half copper. The first metallurgical investigations pioneered by the French team have shown the outlines, but more results are desirable to follow the development in detail.

This brief survey of the history of gold mints should make evident the need for further research. To understand the correlation between monetary circulation and transactions new hoard registers are needed. Regional projects have been initiated to replace Mosser's outdated and cursory bibliography of Byzantine hoards. Aside from the African inventory mentioned above, large scale efforts have been made to begin a regional examination of all fifth to seventh-century hoards from the Balkans,61 with a view toward achieving a better understanding of the Slavic incursions. Another attempt is underway in Italy,62 where smaller museums probably house unknown hoard material. All this work should be undertaken in light of new attributions resulting from recent research. Unfortunately the eastern empire cannot be expected to receive similar coverage. We have to rely on the occasional discovery of recently unearthed hoards, which rarely come from controlled excavations63 but are mainly known through information from the trade. The dawning recognition of the importance of preserving provenances offers a faint ray of hope. Several responsible dealers are to be thanked and encouraged for their efforts in this regard.

A second approach to understanding the coinage is metrology in its broadest sense, which involves investigation not only of weight and fineness, but of the exchange rates between metals — in other words, the price of gold expressed in copper or in kind (adaeratio). Aspects of this question border on the territory of the economic historian, but the numismatic implications are primary, since the coins themselves provide the evidence for monetary reforms or debasements as documented by the introduction of new denominations such as the light weight solidus. Since Adelson's monograph on these peculiar coins of the sixth and seventh centuries, much new material has come to light,64 so that a new corpus of dies might be a promising venture. Meanwhile we have been able to include in this volume a contribution devoted to one aspect of the subject, their distribution. The importance of the light weight solidi for the reckoning of exchange rates has been argued in MIB: they enabled the payment of various sums in carats.

The differentiation between coin units and units of account is a problem which has caused much confusion when related to contemporary texts. Two examples recently discussed in the light of exchange rates (i.e. solidus prices) are the Abydos inscription and the Donori inscription.65 Both give insights into Byzantine taxation policies. Similar problems are encountered when the numerous references to payments recorded in papyri are used for numismatic analysis.66

It has been supposed that the output of the mints was dictated in advance by the authorities of the tax administration, in close connection with taxation policies. This would imply that the volume of an issue was calculated by the expected demands, an idea that has not gone unchallenged.67 Where the solidi are dated by years, we should be able to check the fluctuations in mint activity as soon as we have calculated more reliable estimates of output through die corpora. A comparison with fiscal periods such as taxation cycles and census terms might also provide new insights.68 The financing of the augustaticum, which was to be paid by the emperor to his soldiers on his quinquennial anniversaries, must have been burdensome, since Anastasius I had abolished the collatio lustralis auri argentive in 498.69 Raising of such large sums seems to have been facilitated by monetary measures, such as altering exchange rates from time to time.70 In any case, the economic situation of the empire will be elucidated by better knowledge of the quantities of gold needed in circulation to support taxation on the one hand and, on the other, for the payment of troops, civil servants, subsidies, and tributes. A new compilation of the limited evidence referring to such budget figures would be useful and would facilitate reference to complementary evidence.71

As always, new questions may seem to retard the progress of numismatic research. The authors and editors of this volume have not hesitated to advance their ideas and speculations; nor have they concealed their feelings whenever the assembled numismatic material seemed insufficient to solve inherent problems. Although they differ in their style of presentation, they hope that their comments on the numismatic evidence (of which, it is hoped, some will endure) will be noticed by historians.

| 51 |

I. V. Sokolova, "Nakhodki vizantijskich monet VI-XIvv v Krimu" [Byzantine coin finds of the sixth to twelfth

centuries in the Crimea], VV 29 (1969), pp. 254-68.

|

| 52 |

Add to the five specimens listed in MIB 3, pp. 218 and 242, a piece which came to light in the Schulten sale of 2-3

Nov. 1983, 990, and reappeared in Schweizerische Kreditanstalt sale, 27 Apr. 1984, 700, with commentary.

|

| 53 |

P. Grierson, "Una ceca bizantina en Espa�a," NumHisp 4 (1956), pp. 305-14.

|

| 54 |

Justin II, MIB 2, p. 41, 19; and W. J. Tomasini, The Barbaric Tremissis in Spain and Southern France, Anastasius to Leovigild, ANSNNM 152 (1964), p. 171, pl. D, 7;

Tiberius II, in the museum of Seville, see F. Percz-Sindreu, Catalogo de monedas y medallas de

oro, gabinete numismatico municipal (Seville, 1980), p. 29, 45.

|

| 55 |

The group MIB 3, 101-3, has once more been claimed for Carthage by C. Morrisson, "Note de

numismatique Byzance × propos de quelquss ouvrages r�cents," RN 1983, p. 218.

|

| 56 |

See W. Hahn, "Some Unusual Gold Coins of Heraclius and Their Mint Attribution," NCirc 85

(1977), pp. 536-39, group C, and Hahn (above, n. 41), group C; see also S. Bendall

(above, n. 24), pp. 256-57.

|

| 57 |

MIB 3, pp. 94, 168, and 193.

|

| 58 |

W. Hahn, "Mezezius in peccato suo interiit. Kritische Betrachtungen zu einem Neuling in der Münzreihe der

byzantinischen Kaiser," J�B 29 (1980), pp. 61-70; MIB 3, p. 159. The coin in question was

taken as genuine by P. Grierson, Coins, p. 139, and C. Morrisson

expressed skepticism regarding Hahn's conclusions (at least with respect to the British Museum specimen) in "Note

de numismatique byzantine × propos de quelques ouvrages r�centes," RN 1983, p. 215, n. 8. See now P. Grierson, "A semissis of Mezezius," NC 1986, pp. 231-32, where a coin in Dumbarton Oaks from the

collection of Hayford Pierce (acquired in 1946), omitted from DOC, is reattributed and taken as suggestive of the

authenticity of Mezezius' solidi. Grierson assumes that the coin is of Sicilian fabric, but it shares the

Constantinopolitan style with the solidi and therefore cannot resolve the question. The involvement of an older Italian forger

(Tardani ? —

see RIN 9 [1896], p. 150) cannot be ruled out.

|

| 59 |

DOC 2, p. 17.

|

| 60 |

See Morrisson (above, n. 33), pp. 275-76.

|

| 61 |

Directed by V. Popović, Belgrade.

|

| 62 |

The project "Ripostigli monetali in Italia, documentazione dei complessi" was begun in 1980 by the Civiche raccolte numismatiche

di Milano

and aims to publish hoards of all period, not only the Byzantine.

|

| 63 |

There are, fortunately, exceptions, such as the hoards of Nikertai (above, n. 12) and Rougga (above, n. 30), published by

C. Morrisson, and of Hajdučka Vodenica in Serba, published by N. Duval and V. Popović, Le Trésor de Hajdučka Vodenica, Collection de l'école Française de Rome 75

(1984), pp. 179-82.

|

| 64 |

The 23-carat solidi were not recognized by Adelson, but were identified by E. Leuthold,

"Solidi leggieri da XXIII silique degli imperatori Mauricio, Foca ed Eraclio," RIN 1960, pp. 146-54; for the

introduction of this denomination see also W. Hahn, "A propos de l'introduction des solidi l�gers de 23 carats

sous Maurice," BSFN 36 (1981), pp. 96-97.

|

| 65 |

Abydos has recently been discussed by J.-P. Callu, "Le tarif d'Abydos et la r�forme mon�tairee d'Anastase," T. Hackens and

R. Weiller, eds., Actes du J congr�s international de

numismatique Berne, sept. 1979 (Louvan, 1982), pp. 731-40; W. Hahn, MIB 3, pp. 36-39; and J. Durliat and A. Guillou, "Le tarif

d'Abydos (vers 492)," BCH 108 (1984), pp. 581-98. For Donori see J. Durliat, "Taxes sur

l'ent�e des marchadiseses dans la cit� de Carales-Cagliari × l'�poque byzantine," DOP 36 (1982), pp. 1-14.

|

| 66 |

J.-M. Carr�, "Monnaie d' or et monnaee de bronze dans l'�gypte protobyzantine" Les

'd�valuations' × Rome: �poque r�publicaine et impériale 2 (Rome, 1980), pp.

253-70, and "Comptes et depenses en or," M. Manfredini, ed., Trenta testi greci da papiri

letterarie e documentari editi in occasione del XVII congresso internazionaee de papirologia (Florence, 1983), pp. 112-19.

|

| 67 |

MIB 1, p. 17; MIB 3, p. 85, n. 5, challenged by D. M. Metcalf, "New

Light on the Byzantine Coinage System," NCirc 82 (1974), p. 15.

|

| 68 |

C. Morrisson (above, n. 27), and below, pp. 50-51 and 54-55.

|

| 69 |

For the practice of collatio lustralis in connecionn with the augustiaccum see RE 4, col. 371 (Seeck, Karayannopoulos (above, n. 25), pp. 129-30, and Hendy, Studies (above, n. 5), p. 647. For the abolition of this special kind of taxation see T.

N�ldecke, "Die Aufhebung des Chrysargyron durch Anastasius," BZ 13 (1904), p. 135; for Anastasius'

innovations, J. Karayannopoulos, "Die Chrysoteleia der Iuga," BZ 49 (1956), pp. 72-84.

Contrast R. Delmaire, "Remarques sur le chrysargyre et sa periodicit�," RN 1985, pp.

120-29.

|

| 70 |

See Hahn (above, n. 65), pp. 96-97. Alterations of the exchange rates are denied by Hendy, Studies (above, n. 5), p. 493, and J. Durliat, La valeur relative de l

or, de l'argent et du cuivre dans l'empire protobyzantine," RN 1980, pp. 138-54. Contrast W.

Hahn, "Das Römerreich der Byzantiner aus numismatischer Sicht. West-�stliche Wahrungspolitk der Byzantiner im 5.-8. Jahrhundet,"

SNR 65 (1985), pp. 175-86.

|

| 71 |

For the eighth and ninth centuries see the detailed study of W. T. Treadgold, The Byzantine

State Finances in the Eighth and Ninth Centuries (New York City, 1982).

For the earlier period one had to rely on older studies, e.g. E. Stein, "Zur byzantinischen Finanzgeschichte,"

Studien zur Geschichte des byzantinischen Reiches vornehmlich unter des Kaisers Justinus II. und Tiberius

Constantinus (Stuttgart, 1919) and BZ 1924, pp. 337-87, where references to

earlier, sometimes controversial studies are to be found. See now Hendy, Studies (above, n. 5), pp. 164-81.

|

| 1 |

H. Cohen, Description historique des monnaies frapp�es sous l'empire romain, vol. 8 (Paris, 1892).

|

| 2 |

This includss the empresses Pulcheria, Galla Placidia, Eudoxia II, and Ariadne. For the last see W. Hahn, "Die

M�zpr�gung für Aelia Ariadne," Festschrift für H. Hunger (Vienna,

1984), pp. 101-6.

|

| 3 |

A. S. Robertson, Roman Imperial Coins in the Hunter Coin Cabinet, University of Glasgow 5

(Oxford, 1982).

|

| 4 |

W. Hahn, "De �stliche Gold- und Silberpr�gung unter Theodosius II," LNV 1 (1979), pp. 103-28;

W. Hahn, "Die Ostpr�gung des R�mischen Reiches im 5.Jahrhundet" (in press). O.

Ulrich-Bansa, Moneta Mediolanensis 352-498 (Venice,

1949). For an example of the latter category, see G. Lacam, La fin de l'empire romain el le

monnayage d'or en Italie (Lucerne, 1983).

|

In the spring of 527, Justin I, who had ruled for nine years, fell ill; on April 1, under pressure from the Senate, he co-opted Justinian, whose career he had been promoting since his own accession. Three days later, on Easter Sunday, Justinian I was crowned by the Patriarch Epiphanios; that this event occured in the Delphax rather than, as usual, in the Hippodrome, bespeaks the gravity of Justin's illness. The old emperor (he was 75 or 77) finally succumbdd on August 1.1

The gold coinage of the brief joint reign of Justin and Justinian has attracted little systematic study despite its obvious allure.2 The elegant presentation of two enthroned emperors on the obverse stands out against the otherwise bleak background of the sixth-century gold: moreover, the very brevity of the reign and the rarity of the coins render them a controllable mass and insure that a high percentage of the population surviving above ground is either preserved in major collections or illustrated in sale catalogues.

Alfred Bellinger, who made no attempt at comprehensiveness, was able to assemble a corpus of 33 specimens in 1966; less than a decade later W. Hahn increased the number of recorded specimens to 40, and to 45 by 1981.3 Neither made a systematic study of the dies, although both attemped to classify the bewildering variety of obverse variants and obverse/reverse combinations in trying to educe a structure for the coinage. The purpose of this essay is to present a fuller listing and an ordered catalogue of the coins incorporating its extensive die linkage. It is not claimed that a rational structure can be perceived, and indeed it is plausible that that system, if any, would elude detection even if all the coinage survived to us. But it is possible to take the evidence somewhat further than either Bellinger or Hahn was able to do and, if one can generalize from the experience of a relatively brief episode in the early history of the solidus, to suggest some flaws in the way we now look at imperial mint organization.

In the catalogue, the major categories follow the presentation of Hahn in MIB 1, with numbers romanized for convenience. For varieties of his groups I and II, the obverse dies are prefixed "O" and numbered serially in order of appearance; reverse dies are prefixed with the officina numeral and, within each officina, numbered serially in order of appearance. In group III, the obverses are prefixed "C" (curved); reverses continue the numbering of groups I and II. Weights are given where known, merely for the sake of completeness, since the weights approach the normative 4.5 g; the dies seem to be oriented at 6:00 without variation. All coins are illustrated except nos. 4, 18, 29-30, 41, and 43.

Ia. No cross, no globe

| 1. | O1-B1 | London, BMC 1, 4.48. |

| 2. | O1-Δ1 | London, BMC 2, 4.44. |

| 3. | O1-H1 | a. Padua, Museo Bottacin 2206; b. Bank Leu 13, 4 May 1976, 446, 4.49. |

| 4. | -H | R. N. Bridge, "Some Unpublished Byzantine Gold Coins," NCirc 78 (1970), pp. 246-47, 4, 4.40. |

Ib. No cross, globe

| 5. | O2-I1 | DOC 2, 4.46. |

Ic. Cross, no globe

| 6. | O3-B1 | a. Tolstoi 132, 4.45; b. Hess-Leu, 12 Apr. 1962, 549, 4.50; c. Istanbul, Archaeological Museum. |

Id. Cross, globe

| 7. | O4-B2 | Paris BNC 03/Cp/A//01, 4.46 (pierced). |

| 8. | O5-B2 | a. ANS 1968.131.12, 3.52 (clipped); b. Christie's, 22 Apr. 1986 (Goodacre), 68, 4.42. |

| 9. | O6-ᒥ1 | a. London, BMC 4, 4.39; b. Canessa, 28 June 1923 (Caruso), 657 = Hirsch 24, 10 May 1909 (Consul Weber), 3012, 4.48. |

| 10. | O5-Δ1 | a. Tolstoi 138, 4.4 = Rollin and Feuardent, 20 Apr. 1896 (Montagu), 1096; b. DOC 5b, 4.40. |

| 11. | O7-A1 | H. J. Berk, Roman Coins of the Medieval World, 383-1453 A.D. (Joliet, Ill., 1986), 41, 4.19. |

| 12. | O8-E1 | Rollin and Feuardent, 25 Apr. 1887 (Ponton, d'Am�court), 873. |

| 13. | O5-S1 | London, BMC 5, 4.50. |

| 14. | O9-S2 | London, BM 1918-5–3-2 ex Dewick = Christie's, 5 May 1885 (Tomassini), 4.39. |

| 15. | O10-S3 | a. Whitting = Glendining, 16 Nov. 1950 (Hall), 2212 = Naville 3, 16 June 1922 (Evans), 297, 4.25; b. Glendining, 9 Mar. 1931, 424 (plugged;; c. Kyrenia Girdle no. 3, pl. 8.4. |

| 16. | O6-S4 | NFA 18, 1 Apr. 1987, 658 = Bank Leu 13, 30 Apr. 1975, 574, 4.48. |

| 17. | O8-S4 | Oxford (Evans coll.) =Schulman, 28 Feb. 1939, 92, 3.99. |

| 18. | -S | Photiades cat. 113 see Bellinger [above, n. 2], p. 91, 25, and BMC 5, n.). |

| 19. | O6-Z1 | ANS 1977.158.1025, 4.33. |

| 20. | O11-H1 | Hess 249, 13 Nov. 1979, 459, 4.48. |

| 21. | O12-H2 | Münz. u. Med. 43, 12 Nov. 1970, 541, 4.07. |

| 22. | O5-⊖1 | NFA 18, 1 Apr. 1987, 659, 4.48 = NFA [1], 20 Mar. 1975, 427, 4.47 = Numismatic Fine Arts, vol. 3, 2-4 (Autumn 1974), G155. |

| 23. | O8-⊖2 | a. London, BMC 6, 4.48; b. Berlin 4052, 4.45. |

| 24. | O5-I2 | a. Stack's, 20 Jan. 1938 (Faelten), 1712 = Canessa, 28 June 1923 (Caruso, 658; b. Hess, 30 Apr. 1917 (Horsky), 4692; c. Münzhandlung Basel FPL 13, Nov. 1938, 74 = Ratto 436; d. Hess-Leu 41, 25 Apr. 1969, 734, 4.47. |

| 25. | O5-I1 | Münz. u. Med. 52, 19 June 1975, 823. |

| 26. | O8-I3 | a. Paris, BNC 03/Cp/AJ/02, 4.24; b. Münz. u. Med. 12, 11 June 1953, 909; c. Ratto 437. |

| 27. | O13-I1 | Oxford, Keble coll, 4.45. |

| 28. | O6-I4 | Schotten, H�bl 3470 (pierced). |

| 29. | -I | Turin. |

| 30. | -I | Moustier 3959 (see Bellinger [above, n. 2], p. 91, 26, and BMC 6, n.). |

IIa. No cross, no globe, no crossbar on throne, cushions

| 31. | O14-Γ1 | Kyrenia Girdle no. 2, pl. 8.3. |

| 32. | O15-Z2 | a. DOC la, 4.35; b. Glendining, 17 June 1964, 265 = Glendining, 27 May 1941, 883 = Glendining, 8 Dec. 1922 ("Foreign Prince" [Cantacuzene]), 40. |

| 33. | O16-⊖1 | Tolstoi 135, 4.5. |

| 34. | O17-⊖1 | Klagenfurt, Dreer. |

| 35. | O14-I5 | a. London, BMC 3, 4.45; b. Kastner 10, 18 May 1976, 320 = Sternbeg, 28 Nov. 1975, 568 4.45. |

IIb. Cross, globe, no crossbar on throne, cushions

| 36. | O18-I1 | a. DOC 6b.1, 4.48; b. DOC 6b.2, 4.22. |

IIc. Cross, globe, cushions

| 37. | O19-A1 | Numismatic Fine Arts, vol. 3, 2-4 (Autumn 1974), G154. |

| 38. | O20-A2 | Kunst u. Münzen 12, May 1974, 845. |

| 39. | O21-B2 | a. Bellinger coll., 4.37; b. The Hague, 4.47. |

| 40. | O22-Γ2 | DOC 3, 4.41. |

| 41. | -Γ | Vienna = Longuet, pl. 6, 89. |

| 42. | O23-S5 | a. Paris, BNC 03/Cp/A//03, 4.45; b. Kricheldorf 28, 18 June 1974, 331. |

| 43. | -S | Bucharest. |

| 44. | O24-Z2 | ANS 1962. 170.1, 4.30. |

| 45. | O25-H3 | a. ANS 1968.131.13, 4.34; b. Slocum coll. 1974, 4.45. |

| 46. | O26-H4 | Kricheldorf 30, Apr. 1976, 382 = Kastner 6, 26 Nov. 1974, 430. 4.19. |

| 47. | O26-H5 | Sternbeg, 28 Nov. 1975, 569, 4.45. |

| 48. | O ?-H4 | Tunis, Bardo (El Djem). |

| 49. | O23-⊖3 | Ratto, 26 Jan. 1955 (Giorgi), 1207 = Glending, 14 Jan. 1953, 184 = Ratto 438. |

| 50. | O24-I6 | a. Berlin, Friedbaum, 4.47; b. Hess-Leu 28, 5 May 1965, 564 = Hesperia Art Bulletin 24, [1963], 82 = Münz. u. Med. 25, 17 Nov. 1962, 688. |

| 51. | O27-17 | Cahn 35, 3 Nov. 1913, 578 = Cahn, FPL 24, Nov. 1912, 1938 (MIB "1338"). |

IIIa. No cross, no globe, cushions

| 52. | C1-S3 | a. Hirsch 31, 6 May 1912, 2095 = Hirsch 26, 23 May 1910, 881, 4.50; b. Bank Leu 10, 29 May 1974, 462, 4.47. |

IIIb. Cross, globe, cushions

| 53. | C2-S6 | DOC 7a, 4.47 = Grierson, Coins, pl. 2, 19. |

| 54. | C3-H6 | Tolstoi 141, 4.35 = Rollin and Feuardent, 20 Apr. 1896 (Montagu), 1095. |

| 55. | C4-I8 | Tolstoi 143, 4.25. |

| 56. | C5-I9 | a. Kyrenia Girdle no. 4, pl. 8.2; b. NFA 18, 1 Apr. 1987, 660, 4.51. |

| 1 |

Additional abbreviations used are:

The sources are conveniently summarized in A. A. Vasiliev,

Justin I. An Introduction to the Epoch of Justinian the Great, DOS 1, pp. 95-96; for Justin's death, p.

414. For April 1 as the date of Justinian's installation, see J. R. Martindale, Prosopography

of the Later Roman Empire 2 (Cambridge, 1980), s. v. Iustinianus 7 (pp.

645-48, esp. 647) and Iustinus 4 (pp. 648-51, esp. 650), apparently following the lead of E. Stein, RE 10, col. 1326-27, s. v. Iustinus 1.

|

||||

| 2 |

The fullest treatment is that of A. R. Bellinger, "Byzantine Notes 3: The Gold of Justin

I and Justinian I, ANSMN 12 (1966), pp. 90-92.

See also MIB 1, pp. 44-45, and the Materialnachweise, p. 107.

|

||||

| 3 |

The material assembled by Hahn is augmented in MIB 2, p. 23, and 3, p. 32.

|

Obverse dies show the two emperors (presumably Justin I on the left and Justinian I on the right) nimbate seated facing; the seat may be invisible or partly visible, or may take the form of a rectilinear or "lyre-backed throne. Unless otherwise indicated, the obverse legend is D N IVSTIN ET IVSTINIAN P P AVC. "Globe" indicates that a globe is held in the left hand of the imperial figures, the absence of a notation that the left hand is drawn up to the breast. Notes regarding the knee advanced refer to the figures l. and r. respectively: "r. and l. knees" indicates that the left figure's right knee and the right figure's left knee are advanced, "l. knees" that the left knees of both figures are advanced, and so on.

Ia. No cross, no globe

| O1: | l. and r. knees, Pl. 1: 1-3. |

Ib. No cross, globe

| 02: | l. knees, Pl. 1:5. |

Ic. Cross, no globe

| O3: | r. knees, Pl. 1:6. |

Id. Cross, globe

| O4: | cushion on r. of throne, l. knees, Pl. 1: 7. |

| O5: | l. knees, Pl. 1:8, 10, 13; Pl. 2: 22, 24, 25. |

| O6: | cushion, l. knees, Pl. 1:9, 16; Pl. 2: 19, 28. |

| O7: | r. knees, Pl. 1:11. |

| O8: | D N IVSTIN ET IVSTINI P P AVC, I. knees, Pl. 1: 12; Pl. 2: 17, 23, 26. |

| O9: | l. knees, Pl. 1:4. |

| O10: | l. knees, Pl. 1:15. |

| O11: | r. knees, Pl. 2: 20. |

| O12: | I. knees, Pl. 2: 21. |

| O13: | l. knees, Pl. 2: 27. |

IIa. No cross, no globe, no crossbar on throne, cushions

| O14: | l. and r. knees, Pl. 2: 31, 35. |

| O15: | l. and r. knees, Pl. 2: 32. |

| O16: | l. and r. knees, Pl. 2:33. |

| O17: | l. and r. knees, Pl. 2: 34. |

IIb. Cross, globe, no crossbar on throne, cushions

| O18: D N IVSTIN ET IVSTINAN P P AVC, | l. knees, Pl. 3: 36. |

IIc. Cross, globe, cushions

| O19: | l. knees, Pl. 3: 37. |

| O20: | l. knees, Pl. 3: 38. |

| O21: | N always two unconnected vertical strokes, l. knees, Pl. 3: 39. |

| O22: | l. knees, Pl. 3 : 40. |

| O23: | D N IVSTIN ET IVSTINAN P P AVC, l. knees, Pl. 3: 42, 49. |

| O24: | l. knees, Pl. 3: 44, 50. |

| O25: | D N IVSTIN ET IVSTINIANVS P P AVC, I. knees, Pl. 3: 45. |

| O26: | l. knees, Pl. 3: 46, 47. |

| O27: | l. knees, Pl. 4:51. |

IIIa. No cross, no globe, cushions

| C1: | r. knees, Pl. 3: 52. |

IIIb. Cross, globe, cushions, D N IVSTINV ET IVSTINIANVS P P AVC,

| C2: | l. knees, Pl. 3: 53. |

| C3: | r. and l. knees, Pl. 3: 54. |

| C4: | l. knees, Pl. 3: 55. |

| C5: | l. knees, Pl. 3: 56. |

In the catalogue, the obverse dies are presented in increasing order of complexity of the type and within the major headings according to adjuncts. This preserves the essence of Hahn's system, which is based on the shape of the throne, the presence or absence of a cross, and presence or absence of a globe. These are by no means the only diagnostics that might have been chosen. Bellinger, who first drew attention to the varieties of throne type, also noted that the presentation of the imperial figures is not consistent throughout: either may have either knee advanced, and it may be the same as or opposite to that of his partner. Bellinger noticed the differences in obverse legend that are observed here without, apparently, attaching any significance to them; Hahn ignored the legends entirely. The presence or absence of a cross has elicited no detailed comment.4 After a lengthy discussion of such variations in the obverses, Bellinger concluded that they are not the idiosyncrasies of die engravers and that the divergencies are not demonstrably connected. He remarked, "We can only conclude that a number of engravers, working in a hurry, produced dies which conformed in general, to be sure, but which were not strictly controlled as to details."5 The "hurry" factor is often associated with short reigns, but except insofar as we suppose a pressure for immediate coinage at an imperial accession, Grierson is quite right to remark that short reigns are only short in retrospect, and that contemporaries could hardly have foreseen their brief duration.6

Yet within this broad context of supposed haste and consequent jumbling of attributes, some aspects of the types have been thought significant. Bellinger, for example, supported Wroth's distinction between styles 1 and 2, the former characterized by clasped hands, the latter by the left holding a globus. Bellinger remarks, "One hesitates to speak of a sequence of issues in a period of only four months but it may be suggested that the superior majesty of Type 2 was felt to be more appropriate than the superior piety of Type l."7 Hahn's discussion is brief and, in part, derivative from Bellinger's. Like Bellinger he sees chronological significance in the shift from folded arms to globus in left; and for him the variable seating arrangements (no throne/throne/lyre-backed throne) are the hallmarks of three different die engraves..

None of this will withstand examination. Hahn's own observation of the frequent linkage among obverse types, further elaborated here, disposes of any chronological significance they might be supposed to have, since no consistent pattern emerges. Note, for example, the following shared reverses:

B1: groups Ia and Ic

B2: groups Id and IIc

Γ1: groups Id and IIa

Δ1: groups Ia and Id

Z2: groups IIa and IIc

⊖1: groups Id and IIa

I1: groups Ib and Id

Dies paired with obverses of group Id are those most commonly linked with obverses of other groups, but by any measure that is the most common variety in the series and its linkage to the others would be expected to be most frequent. No single attribute or adjunct appears with sufficient consistency among the groups to be taken as a chronological signpost unless we suppose the simultaneous striking of three very different obverse styles; in that case we would be reduced to discussing nothing more than the relationship of the dies inter se, a bootless endeavor. What may be significant—though not necessarily in chronological terms—is the elaboration of the throne.

The most elaborate of the thrones that appear on the coinage of the joint reign is commonly called "lyre-backed," for obvious reasons. Until the study of Cutler in 1975,8 this form had attracted hardly any attention at all, perhaps because its representation is confined to coins. In a study of the appearance of the motif he concluded, largely from overwhelming ex silentio arguments, that there is no evidence for the existence of the lyre-backed throne as a piece of furniture, and that its significance is therefore to be sought in its symbolism. To summarize broadly (and without considering its possible orphic origins and implications), this throne may be seen as the medium by which the Logos, through intermediaries, harmonized the conflicts of the world. It originally had the connotation of wisdom, but this was eventually forgotten and the form degenerated so far as to become virtually unrecognizable.

This interpretation is certainly consistent with the coins of the joint reign, both politically and numismatically. The association of Justinian I in the rule was clearly intended to formalize his succession to the elderly emperor, who was either 75 or 77 years old at the beginning of 527. The coinage, like the events of Holy Week, simply confirmed a longstanding dynastic plan that would be the signal achievement of Justin's rule.

The view that the type is to be read only in such broad terms is reinforced by the casual admixture of other symbolic forms—globe and cross as attributes and adjuncts—as well as inattention to sometimes die-specific variants in legends meant to be perceived as formulaic, quite apart from the information they conveyed.9

| 4 |

The cross which usually appears between the heads of the emperors on the obverse was called by Bellinger a cross potent, but if it is properly potent at all the termini of the cross are attenuated at best. This

identification of the cross led A. Cutler, "The Lyre-backed Throne," Transfigurations: Studies

in the Dynamics of Byzantine Iconography (Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, 1975) to

observe that the use of the cross potent during the reigns of Justin and Justinian

seems to be confined to the coins; but while there are clear examples in the coinage of Justinian alone, the joint reign solidi

are not the

best evidence for the phenomenon.

|

| 5 |

Bellinger (above, n. 2), p. 92.

|

| 6 |

P. Grierson, "Coins mon�tairess et officines × l'epoque du Bas-Empire," SM 11 (1961), pp.

1-8, esp. p. 5.

|

| 7 |

Bellinger (above, n. 2), p. 91.

|

| 8 |

Cutler (above, n. 4), pp. 5-52, esp. 6-11 and 38-40. A. Grabar, L'empereur dans l'art

byzantin (Strasbourg, 1936, rpt., London, 1971), pp. 199-200, had already noted the significance of the throne as a cult object dating

back to early Roman times.

|

| 9 |

The omission of AN from the obverse of O8 is unique, as are the disconnected Ns of O18. It would be easier to take IVSTINAN

as a simple

misspelling if it did not occur twice (O16, O20). Similarly the form D N IVSTIN ET IVSTINIAN P P AVG, dominant in classes

I and II, occurs

a single time (C1) in class III, while that class's dominant fuller form occurs once in class II (O22). It should be recognized

that such

variations, which are often useful and used in cataloguing, may bear no relation to mint organization.

|

In contrast to the obverse, which stands out against the sixth century solidi, the reverse type continues that employed on the issues of Justin I, which was later to be carried over into the sole reign of Justinian and later still adapted by varying the ornament surmounting the cross in the angel's right hand. A quick survey of the coins of the flanking reigns of Justin I and of Justinian I seems to suggest that the reverses of the joint reign owe more to their predecessors struck under Justin than the coins of Justinian do to either in terms of style: by comparison, the coins of Justinian show a generally more squat angel whose wings do not rise as high vis × vis his head: the drapery is rendered with less care, and the placement of the feet often suggests a figure in motion rather than static.

It is possible—in fact, likely—that some reverse dies of Justin and Justinian were originally employed during the sole reign of Justin, and that some continued in use when Justinian achieved sole power in August of 527. A careful search would be tedious but would probably repay the effort. It has not been undertaken here because unless such links were to be found in numbers they would not significantly alter the picture of the coinage suggested here. What is needed is a more refined view of the internal chronology of the coinage than is possible in the present state of the evidence.

The careful marking of reverse dies in the Byzantine coinage seems to attest the most rigid subdivision into officinae observed in any ancient coinage. Although the internal structure of the mint is not perfectly understood, it is at least clear that the concept of discrete, independently functioning workshops is to be avoided. This was first observed by Grierson, and has subsequently been reinforced by the occasional occurence of die linked solidi of different officinae in hoards.10

Here the instance of dies shared among officinae must surely be as high as is to be observed in any sample of Byzantine coins. Die O1 is found with reverse dies from B (1) Δ (2), and H (3a-b); O5 with B (8a-b), Δ (10a-b), S (13), ⊖ (22), and I (24a-b, 25); O6 with Γ (9a-b) and S (16); O8 with E, S, ⊖, and I (12, 17, 23a-b, 26a-c), and so on. In the present sample there is no evidence of a systematic association of pairs or triplets of officinae, and it has to be supposed that the distribution of dies among the workshops reflects their drawing upon a common pool of dies (a die box) for the production of reverses. It is of course equally plausible that the obverses, too, came from die boxes, since there is nothing which would suggest their attachment to specific officinae, and indeed the likelihood of this construct grows as obverses begin to appear linked with dies of three or more workshops.

In spite of the small size of the sample, it may be worthy of note that there is no certain instance of recutting of dies

to be observed,

either within or among officinae and despite the existence of die  3 with the number reversed.11

3 with the number reversed.11

Heretofore it has never been supposed that these coins were struck anywhere but Constantinople. There is clear evidence for the existence of a mint for gold at Thessalonica for the emperors from Anastasius I onwards—sometimes gold that would on the basis of its markings have been taken to be Constantinopolitan—but no one to date has hinted at the existence of a non-metropolitan mint for the brief joint reign.12

In fact if Cutler's analysis is credited and the throne is stripped of its pictorial literalism, and if this is combined with the discreteness of the lyre-backed group, it is possible, at least for now, to suggest the existence of a mint at Thessalonica. For none of the lyre-backed solidi display reverse die links to throneless or square-backed ones, while within those two groups die linkage is common.

It is dangerous to be dogmatic in enumerating stylistic differences on the basis of as few as seven specimens from five obverse dies but, for what it is worth, the obverses of group III generally display taller, more vertically oriented figures seated on the throne, which is itself rendered with more care and consistency than those shown on the coins with straight back of group II. The angel on the reverse maintains the same posture throughout, and his right wrist leading up to the cross is impossibly long. The star in the field is uniformly large, while some variation in size is to be observed on coins of the other two groups. Against the use of style as a dissociative criterion are certain features which, if not identical, at least display the same kind of variation as has been noted in groups I and II: for example, on obverse die C1 the outside knees of both emperors are advanced, while on all the other dies the right ones are forward; C1 also lacks the cross in field which is present on all other dies. Similarly C1 is without the globe, which is present elsewhere, and it has short form of obverse legend which is characteristic of groups I and II. I have not been able to examine the coins struck from this die, but just possibly the lyre-backed throne has been recut from a rectilinear one. If so, the hypothesis of a second mint is obviously weakened.

| 10 |

P. Grierson (above, n. 6), p. 4. For die links among officinae see W. E. Metcalf,

"Three Byzantine Gold Hoards," ANSMN 25 (1980), pp. 87-108, especially hoard 2, nos. 3 and 7, 4 and 6, 26 and 36, 34

and 39, 50 and 54, all pairing coins of different workshops; C. Morrisson, "Le trésor byzantin de Nikertai," RBN 118 (1972), pp. 29-91, esp. 40-43 and fig. 5.

|

| 11 |

But see below, p. 26.

|

At the very least the picture of the coinage of Justin I and Justinian I is more complicated than expected. Grierson had already pointed to the fairly frequent linkage among officinae, which is more common than the existence of a system for their numeration would imply; his view is confirmed here, with its implications extended into the sixth century. Similarly minor variations in legend and in distribution of attributes and adjuncts cannot be seen here—as they are sometimes seen elsewhere—as the trademarks of engravers or as secret marks that somehow, if decoded, might elucidate the working routine of the metropolitan mint.

Allowance must be made for the "hurry factor"; even if "short reigns are only short in retrospect," the illness of Justin gave more than the usual urgency to a proclamation coinage, and this might be reflected in unusual steps taken to hasten its production. Nonetheless, the coinage presents a surprisingly disorganized aspect which, if it may be generalized to the sixth century coinage at large, reduces the reliability of some time-honored simple solutions to complex problems, and invites the painstaking analysis, die by die, of a forbidding mass of material.

The Approximate Size of the Coinage

A die study of this sort provides the opportunity to estimate the numer of dies used for this coinage from the number represented in the surviving sample. Any number of methods have been devised for this calculation, but the formula applied here is that of Carter,

where n = the number of coins and d = the number of dies observed and n < 2d or

where n = 2 to 3d.13

Six specimens (4, 18, 29-30, 41, and 43) have been omitted from the calculations since no photographs are available, leaving a total of 73 pieces from 37 reverses dies. For the obverses, two calculations must be made because of uncertainty regarding the identity of the obverse of coin 48: the first assumes that it is identical to another known obverse, the second assumes that it is not, so d1 = 32 and d2 = 33 obverses. Carter's formulae yield the following results: 1) projects an estimate of 47 × 4 obverse dies, 2) 50 × 5 obverse dies, while both yield an estimate of 61 × 7 reverse dies. Since these two calculations embrace the whole coinage, including two bodies of material that are immiscible (groups I and II do not and, in the case of the obverses, cannot share dies with group III) it is perhaps sounder methodologically to provide a separate calculation for groups I and II only: thus from 65 coins with 1) 27 or 2) 28 obverse dies, and 32 reverse dies, the results are as follows: 1) 38 × 4, 2) 41 × 4 obverses, and 51 × 6 reverses. Adding these projections to the actual number of dies observed for group III (which is too small to apply the method meaningfully) produces satisfactory consistency. An estimate of the total original die population at ca. 50 obverses and 60 reverses will not be far from the truth.

The joint reign lasted only 17 weeks, and there is no reason to suppose that the coinage began before it or continued after it. Even in this period, which might well have been one of heavy coinage in view of the imperial accession, somewhat less than an obverse a day was used if the work week consisted of five days.

| 12 |

Prof. P. Grierson, who generously made available to me photographs accumulated over many years, had segregated

the coins of group III known to him, and marked them with "Antioch (?)."

|

| 13 |

See G. F. Carter, "A Simplified Method for Calculating the Original Number of Dies from Die Link Statistics," ANSMN 28 (1983), pp. 195-206, esp. 201-2. The attraction of the Carter method is the simplicity of its application,

especially where high precision does not yet seem attainable. For evaluation of this and other methods currently employed

in estimating

size of coinage, see W. W. Esty, "Estimation of the Size of a Coinage: A Survey and Comparison of Methods," NC 146 (1986), pp. 185-215.

|

Some ten years ago on Monte Judica in the province Catania, Sicily, a hoard of sixth-century gold coins appeared. This hoard is essential for understanding the activities of the smaller Byzantine gold mints in the western half of the empire and is comparable only to the 1948 Thessalonica hoard's materials for mint attributions in the East. The coins had been concealed in an unglazed terracotta pot which, regrettably, has since been lost. The hoard was immediately split up, and some of the coins were dispersed in trade via Switzerland.1 We are are indebted to S. Bendali and H. Berk for certain information about the coins which has led to the following reconstruction of the hoard.

Constantinople, MIB 7, 507-18, solidus

| 1. | Z | 4.49 | Munz. u. Med. FPL 434, June 1981, 19 |

Constantinople, MIB 5, 527-37, solidus

| 2. | Γ | 4.46 | |

| 3. | Δ | 4.50 | |

| 4. | ϵ | 4.48 | |

| 5. | ϵ | 4.45 | |

| 6. | ϵ | ||

| 7. | S | 4.46 | |

| 8. | S | 4.46 | |

| 9. | Z | 4.48 | |

| 10. | Z | 4.44 | |

| 11. | Z | ||

| 12. | ⊖ | 4.38 | |

| 13. | I | 4.48 | |

| 14. | I | 4.47 | |

| 15. | I | 4.46 | |

| 16. | I |

MIB 6, 537-42, solidus

| 17. | A | 4.47 | |

| 18. | A | 4.46 | |

| 19. | A | ||

| 20. | A | ||

| 21. | B | 4.46 | |

| 22. | Γ | 4.47 | |

| 23. | S | ||

| 24. | Z | ||

| 25. | H | 4.41 | |

| 26. | ⊖ | 4.49 | = Schweizer. Kredit. 2, 27-28 Apr. 1984, 740 |

| 27. | ⊖ | ||

| 28. | I |

MIB 7, 542-65, solidus

MIB 19, 527-65, tremissis

| 56. | 1.46 | ||

| 57. |

Thessalonica, MIB 23, 562-65, solidus

| 58.Obv. of Thes. hd. 23. | 4.46 |

Carthage, MIB 25, 547/8, solidus

| 59. | IA | 4.43 | = Schweizer. Kredit. 2, 27-28 Apr. 1984, 741 |

| 60. Obv. of DOC 277 a. 1. | IA | 4.49 |

Rome, MIB 31-32, 540-42, solidus

| 61. | 4.44 | = Schweizer. Kredit. 2, 27-28 Apr. 1984, 742 |

MIB, 34, 542-49, solidus

| 62. | A | 4.47 | |

| 63. Rev., no star. | A | 4.45 | |

| 64. | Γ | 4.47 | = Schweizer. Kredit. 2, 27-28 Apr. 1984, 743 |

| 65. Rev. of BM and Birmingham specimens. | Z | 4.43 | |

| 66. Rev. of Ratto 1955, 1209 | ⊖ | 4.40 | = Schweizer. Kredit. 2, 27-28 Apr. 1984, 744 |

Ravenna, MIB 37, 549-65, solidus

| 67. Dies of Ratto 459 | Γ | 4.45 | = Schweizer. Kredit. 2, 27-28 Apr. 1984, 745 |

| 68. | Γ | 4.48 | |

| 69. Rev. legend error | S | 4.44 | = Schweizer. Kredit. 2, 27-28 Apr. 1984, 746 |

| 70. Obv. of Ratto 461 | г |

Sicily, MIB 37 [Ravenna], 554/5?, solidus

| 71. | Г | 4.47 |

555/6 ?, solidus

| 72. | Δ | ||

| 73. Obv. of 72. | Δ | ||

| 74. | Δ |

MIB 41 [Ravenna], 542-65, tremissis

| 75. |

| 1 |

Münz. u. Med.'s FPL 434, June 1981, contained some coins of this hoard (as indicated in the catalogue) and Schweizerische

Kreditanstalt

2, April 1984, included others. The references given in the latter were taken from an older version of this article and in

the course of

refinement, the numbers were changed. The discovery date of the hoard, claimed to be 1981 by some informants, could not be

verified.

|

Constantinople, MIB 5, 567-78, solidus

| 76. | A | 4.44 | |

| 77. | A | ||

| 78. | Є | 4.51 | |

| 79. | H | ||

| 80. | I | 4.49 |

MIB 11a, 565-78, tremissis

| 81. |

Thessalonica, MIB 16, ca. 570, solidus

| 82. | 4.48 | = Münz. u. Med. FPL 434, June 1981, 21 |

Ravenna, MIB 20c, 567-ca. 570, solidus

| 83. Obv. of Thes. hd. 110. |

|

4.44 |

MIB 21, ca. 570, solidus

| 84. | P | 4.47 | = Schweizer. Kredit. 2, 27-28 Apr. 1984, 747 |

Sicily, MIB 21 [Ravenna], 568/9, solidus

| 85. Rev. CNONB. | B | 4.50 | = Schweizer. Kredit. 2, 27-28 Apr. 1984, 748 |

| 86. Dies of 85. | B | 4.45 |

569/70

| 87. | Γ | = Münz. u. Med. FPL 434, June 1981, 20 |

570/1

| 88. Obv. of 85. | Δ | 4.45 | |

| 89. Dies of 88. | Δ | 4.45 | |

| 90. | Δ | 4.48 | = Schweizer. Kredit. 2, 27-28 Apr. 1984, 749 |

| 91. Obv. of 90. | Δ | 4.46 | |

| 92. Dies of 91. | Δ | 4.46 | = Schweizer. Kredit. 2, 27-28 Apr. 1984, 750 |

571/2

| 93. Obv. of 90. | Є | 4.46 |

MIB 24 [Ravenna] ca. 570, semissis

| 94. Rev. VITC... | 2.24 |

Tremissis

| 95. Rev. Victory facing 1. | 1.50 | = Schweizer. Kredit. 2, 27-28 Apr. 1984, 751 | |

| 96. Obv. of 95. Rev. Victory facing r. | 1.52 | = Münz u. Med. FPL 434, June 1981, 22 | |

| 97. | 1.51 | = Schweizer. Kredit. 2, 27-28 Apr. 1984, 752 | |

| 98. | 1.47 |

It seems probable that the hoard has been reconstructed as fully as possible. The 98 coins are distributed as follows.

| Con. | The. | Car. | Rom. | Rav. | Sic. | |||

| Anastasius I, | 1 | Sol. | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |