The basic chronological framework for the arrangement of Nero's coinages is provided by the elements of imperial titulature found on the coins. Nero held the consulship five times, in 55, 57, 58, 60 and 68, 1 and his first and fourth consulships are recorded on the gold and silver. 2 Considerably more important are the series of tribunician dates found on the pre-reform aurei and denarii and on a limited number of the later sestertii and dupondii, and the use of "imperator" as a praenomen during the later years of his principate. Unfortunately both the reckoning of Nero's tribunicia potestas, and the date when he assumed the praenomen imperator have been disputed.

Nero celebrated the renewal of his tribunician power on 4 December, 3 fifty two days after his dies imperii of 13 October. 4 He counted it from 4 December 54, and added one to each TRP number on 4 December in each succeeding year. Apart from this unusual starting date, there is no need to assume any irregular reckoning.

The supposed difficulty in calculating Nero's TRP has been the apparently contradictory entries in two surviving fragments of the Arval Acta. For 3 January 59 Nero's titles are given as TRP V …, 5 but both the general heading for 60 and the specific entry for 3 January of that year have TRP VII IMP VII, 6 whereas on a normal reckoning one would expect to find TRP VI IMP VII. This gave rise to Mommsen's view that during 59 Nero changed his TRP renewal day to 10 December (the day of the consilia) and subsequently counted TRP I as 15 October to 9 December 54 with TRP II as 10 December 54 to 9 December 55. Nero would thus regard TRP VII as 10 December 59 to 9 December 60. 7 We now know that the Arval Acta commemorated Nero's dies imperii on 13 October in 58 4 and the bestowal of his tribunicia potestas on 4 December in both 57 and 58 3 —the sole years for which the relevant parts of the Acta survive. Any alterations, therefore, in numbering Nero's TRP cannot have been occasioned by a change in the starting date of the tribunician year. The 4 December was already in use by 57, whereas the discrepancy in the numbering of Nero's TRP does not appear until after the entry for 59.

The other epigraphic and numismatic evidence 8 supports a straightforward reckoning of Nero's TRP from 4 December 54. Most inscriptions merely establish a connection between a particular TRP date and the number of an imperial salutation. Three inscriptions, however, have an additional external date. The military diploma in Vienna granted to Iantumarus 9 is unfortunately indecisive. Although it gives a consular dating AD VI NON IVL CN PEDANIO SALINATORE L VELLEIO PATERCVLO COS besides TRIB POT VII IMP VII COS IIII in Nero's titles, the date of their suffect consulship is uncertain. 10 But the other two inscriptions are more helpful. Lucretianus' dedication from Luna 11 shows Nero as TRIB POTEST VIIII IMP VIIII and Poppaea as Poppaea Aug Neronis Caesaris Aug Germ. Poppaea gave birth to a daughter, Claudia, in 63 and both she and the child were given the title of Augusta immediately afterwards. 12 The Luna dedication thus supports the straight calculation which would make TRP VIIII December 62/63. On Mommsen's system TRP VIIII would have to be December 61/62 which is a year too early. The Boeotian inscription from Acraephia recording Nero's declaration of liberty to Greece 13 and Epameinondas' speech of thanks, has δημαρχικῆς ἐξουσίας τὸ τρισκαιδἐκατον. Hammond has shown that the assembly took place on 28 November 67, 14 and this again supports the straight calculation which would make TRP XIII December 66/67.

Nero's gold and silver coinage forms a regular series from TRP to TRP X without interruption, and gives no suggestion of any change in tribunician reckoning. The aurei and denarii of 60 have the normal COS IIII TRP VI. 15 This issue seems to be the production of a complete year, and its TRP date directly contradicts the entry in the Arval Acta of COS IIII TRP VII for 3 January of the same year.

In other circumstances one might have allowed the evidence of the Arval Acta, the record of a public college quite closely connected with the Imperial House, against the authority of a dedication from Luna and of an inscription from Boeotia; but the Luna dedication and Acraephia inscription are supported by the clear evidence of the COS IIII TRP VI aurei and denarii from the mint of Rome (see Table 1 below), an institution far more official and imperial than a public college. As these coins are struck from several distinct dies, this date can hardly be regarded as an error. The only evidence for the so called 'Arval reckoning' is the double entry in the Acta of COS IIII TRP VII for January 60, and a very good case can be made for regarding these as a mistake. There is in fact a surprisingly large number of minor errors in the Acta of this period, e.g.,

A.D. 57 16

l. 14. ob tribuniciae (sic) potestat. Neronis Claudi …

l. 23/4. immolavit/in sacram viam (sic) memoriae Cn ….

A.D. 58/9 17

l. 58. L. Piso L. f. magiter (sic)

l. 62/3. M. Apronius Saturnius (sic—for Saturninus)

A.D. 59/60 18

a. l. 15. C. Vipstanus (sic) Apronianus cos P Memmiu (sic)

l. 26. August Germanicii (sic) Iovi

d. l. 16. Caesari (sic) Aug Germanico (to agree with consule).

The imperial titles for 3 January 59, moreover, are given as TRIB POT V IMP VI COS III DESIG IIII; 19 a designation to COS IIII so far ahead as 3 January is most unlikely in view of the constitutional show which Nero's principate was anxious to maintain at this period 20 and it is likely that an entry proper to the closing months alone of the year has been put in full for 3 January. The entry COS IIII TRP VII for 3 January 60 appears to be a closely comparable error. When the Acta for 60 were formally written up at the end of the year, the engraver apparently inserted the current year's date COS IIII TRP VII (December 60/61), for January 60—an error which it would be extremely easy to make by assimilation to the neighboring IMP VII.

| 1 | |

| 2 |

Cat. 3, 9ff., 37, 42 ff.

|

| 3 |

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (hereafter CIL) VI, 2039, 2041.

|

| 4 |

CIL VI, 2041.

|

| 5 |

CIL VI, 2041.

|

| 6 |

CIL VI, 2042.

|

| 7 |

Theodor Mommsen, Hermes 2 (1856), p. 56 and Römisches Staatsrecht II (3rd ed., Leipzig, 1887), pp. 796ff. Mommsen has been followed by B. W. Henderson, Life and Principate of the Emperor Nero (London, 1903), Appendix C., p.449; L. Constans, "Les puissances tribuniciennes de Néron," Comptesrendus de l'Académie des inscriptions et belle-lettres (CRAI) 1912, p. 385; E. A. Sydenham, The Coinage of Nero (London, 1920), pp. 23–28; and R. Cagnat, Cours d'épigraphie latine (4th ed., Paris, 1914), pp. 183ff. Mommsen's view has been attacked by H. F. Stobbs, Philologus 32 (1873), pp. 1–91; H. Dessau, Geschichte der römischen Kaiserzeit II (Berlin, 1926). p. 196, note 1 and in notes to inscriptions in Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae (ILS); H. Mattingly, "The Date of the 'Tribunicia Potestas' of Nero and the Coins," NC 1919, pp. 199–200 and "'TRIBVNICIA POTESTATE.'" JRS 1930, pp. 78–91 and M. Hammond, "The Tribunician Day During the Early Empire," Memoirs of the American Academy in

Rome 1938, pp. 23–32.

|

| 8 |

See Table 1, pp. 6–7 below.

|

| 9 |

CIL XVI, 4. (= ILS 1987).

|

| 10 |

Degrassi, I fasti, pp. 16–17.

|

| 11 |

CIL XI, 6955.

|

| 12 |

Tacitus, Annals xv.23. On the right hand edge of the stone of this dedication are the remains of the D and N, one above the other, which

seem to stand for D(ivae Claudiae …) N(eronis …)—and provide an additional argument for dating the inscription to a.d. 63. It is interesting to note that Lucretianus was apparently very careful to record the imperial titulature correctly. His

second dedication dated TRP XIII gave Nero the praenomen IMP, whereas his dedication of a.d. 63 did not. The numismatic evidence shows that Nero assumed the praenomen IMP during the course of TRP XII.

|

| 13 |

Inscriptiones Graecae (IG) VII, 2713.

|

| 14 |

Hammond, "Tribunician Day," p. 28, following M. Holleaux, BCH 1888, pp. 510–28 and more fully in his Discours prononcé par Néron à Covinthe en rendant aux Grecs la liberté, 1889; and Dittenberger, IG VII, 479.

|

| 15 |

Cat. 9, 42.

|

The other important chronological indication is Nero's use of IMP as a praenomen 21 from 66. All the known inscriptions dated TRP XII (December 65/66) and later have the praenomen IMP, whereas those dated TRP—TRP XI never have it. The Acta for 66 repeatedly refer to IMP NERO 22 whereas in the proceedings up to and including 60 (the last year before 66 where Nero's titles are recorded) Nero is never given the praenomen. Titinius' dedication at Luna dated TRP XIII IMP XI COS IIII (December 66/67) 23 is to Diva Poppaea and Imp Nero, whereas his earlier dedication in TRP VIIII (62/63) 24 repeatedly gives Nero's titles without the praenomen. The Acraephia inscription 25 dated TRP XIII gives Nero the praenomen αὐτοκράτωρ; and the Sardinian milestone dated TRP XIII IMP XI 26 has the praenomen IMP. An apparent exception, the stone from Casino 27 (no longer extant), seems to have been incorrectly transcribed. It is reported without the praenomen and dated TR POT XIII IMP VIII (sic). But this is an impossible combination which cannot be accepted, and TR POT VIII IMP VIII, a conjunction known from another inscription, 28 is the obvious emendation.

Sestertii and dupondii with TRP XIII all have the praenominal IMP and so do the rare coins dated TRP XIV. But the praenomen was never used on the aurei and denarii dated TRP—TRP X, 29 nor on the cuirassed bust sestertii. 30 The date on these has been variously read as TR POT XI PPP, 31 TR POT XII PP, 32 TR POT XI PIP, 33 TR POT XI PPI, 34 and TR POT XIIII; 35 but all the specimens which the author has examined are struck from the same obverse die with TR POT XI PPP. 36

The dated and undated coinage, moreover, shows clearly that once adopted, the use of the praenomen remained the regular form. The most mature portraits of Nero, with a thick treatment of the neck and a heavily developed jowl, are always found on coins with the praenomen.

The terminus post quem for the assumption of the praenomen is given by the cuirassed bust sestertii dated TRPOTXIPPP and the three inscriptions dated TRPXI. The terminus ante quem is fixed by the entries in the Arval Acta for 66, with the caveat, perhaps, that the titulature may have been correct only for the end of the year when the record was completed. Within these limits it is difficult to be more precise. Either the Vinician conspiracy of 66, 37 or the ceremonial reception of Tiridates at Rome during the summer of the same year 38 are equally possible occasions. But although the precise context remains obscure, the praenomen is most important chronologically and enables us to distinguish the later groups in the undated coinages.

| TRP | Aurei | Cat. 2, 3. |

| Denarii | Cat. 36, 37. | |

| TRP II | Aurei | Cat. 4. |

| Denarii | Cat. 38. | |

| Inscr. | AE 1897.30 (IMP II COS). | |

| TRP III | Aurei | Cat. 5, 6. |

| Denarii | Cat. 39. | |

| Inscr. | CIL II, 183 (IMP III COS II DES III); II 4734 (IMP III COS II DES III). | |

| TRP IIII | Aurei | Cat. 7. |

| Denarii | Cat. 40. | |

| Inscr. | CIL IX, 4115 (IMP COS III); VII, 12 (IMP IIII COS IIII sic); XII, 5471 (IMP IIII COS III PP); XII 5473/5; III 346 (IMP V COS III). |

| TRP V | Aurei | Cat. 8. |

| Denarii | Cat. 41. | |

| Inscr. | CIL II, 4657 (IMP II sic); II 4652 (IMP IIII sic); II 4683 (IMP IIII sic); VI 2042 (IMP VI). | |

| TRP VI | Aurei | Cat. 9. |

| Denarii | Cat. 42. | |

| TRP VII | Aurei | Cat. 10, 11, 12, 13. |

| Denarii | Cat. 43, 44, 45, 46. | |

| Inscr. | CIL XVI, 4 (IMP VII COS IIII); VI 2042 (IMP VII COS IIII). | |

| TRP VIII | Aurei | Cat. 14, 15, 16. |

| Denarii | Cat. 47, 48, 49. | |

| Inscr. | CIL III 6123 (IMP VIII COS IIII PP); II 4888 (IMP VIIII COS IIII). | |

| EE VIII p. 365 (COS IIII IMP VIII PP); AE 1900, 18 (IMP VIII COS IIII PP). | ||

| TRP VIIII | Aurei | Cat. 17, 18, 19. |

| Denarii | Cat. 50, 51. | |

| Inscr. | CIL XI, 6955 (IMP VIII COS IIII). | |

| TRP X | Aurei | Cat. 20, 21. |

| Denarii | Cat. 52, 53. | |

| Inscr. | AE 1947, 167 (IMP VIII COS IIII PP). | |

| TRP XI | Inscr. | CIL III, 6741/42 (COS IIII IMP VIIII); AE 1919, 22 (IMP COS IIII PP). |

| Sestertii | Cat. 135, 136. | |

| TRP XII | — | |

| TRP XIII | Sestertii | Cat. 167–74. |

| Dupondii | Cat. 238–41. | |

| Inscr. | CIL X 5171 (IMP VIII sic); XI 1331 (IMP XI COS IIII); IG VII 2713. | |

| TRP XIV | Sestertii | Cat. 175, 176. |

| Inscr. | CIL X 8014. | |

| TRP XV | — |

| 16 |

CIL VI, 2039.

|

| 17 |

CIL VI, 2041.

|

| 18 |

CIL VI, 2042.

|

| 19 |

CIL VI, 2041.

|

| 20 |

C. H. V. Sutherland, Coinage in Roman Imperial Policy (London, 1951), pp. 152ff.

|

| 21 |

Later emperors regularly included the praenomen in their titulature from their accession, but this practice did not go back

further than Vespasian. Cf. D. McFayden, History of the Title Imperator under the Roman Empire (Chicago, 1920).

|

| 22 |

CIL VI, 2044.

|

| 23 |

CIL XI, 1331.

|

| 24 |

CIL XI, 6955.

|

| 25 |

IG VII, 2713.

|

| 26 |

CIL X, 8014.

|

| 27 |

CIL X, 5171.

|

| 28 |

CIL XI, 1331.

|

| 29 |

Cat. 2–21, 36–53.

|

| 30 |

Cat. 135–36.

|

| 31 |

L. Laffranchi, "Il predicato P(ROCOS) dei sesterzi di Nerone e la Profectio Augusti," AttiMemIIN 4 (1921), pp. 47–62.

|

| 32 |

BMC RE I, p. 215, note on no. 111.

|

| 33 |

BMCRE I, no. 112.

|

| 34 |

BMCRE I, no. 111.

|

| 35 |

Cohen, Description historique des monnaies frappées sous l'empire romain (2nd ed., Paris, 1880–92) I. Nero 260 quoting the Wigan collection.

|

| 36 |

Ingemar König's recent study, "Der Titel «Proconsul» von Augustus bis Traian," SM 1971, pp. 42–53 republishes and illustrates six of these sestertii.

|

| 37 |

McFayden, Imperator, pp. 58–59.

|

| 38 |

Suetonius, Nero 13.2.

|

Some varieties of obverse and reverse legend and type are characteristic of the mints at which the coinage was struck, and the chronological pattern of the issues cannot be determined until the basic mint structure is appreciated. The evidence of finds shows clearly that Rome was the sole mint for the issue of precious metals in the west, but that there were two principal mints, Rome and Lugdunum, for the aes coinages.

From these western issues we must be careful to distinguish the coinages struck by a wide range of mints in the eastern provinces. There is little difficulty over the product of city mints which employed Greek legends or of colonies which added to their Latin legends the initial letters of the name of the colony. 1 Rather less obvious are the coins with Latin legends struck by the imperial mints at Caesarea 2 and Antioch 3 and by the military mint in Moesia, 4 but each of these series is characterized by a distinctive range of reverse types.

Nero's coinage of aurei and denarii in both the dated and the undated series is remarkably uniform in style, type and content. Coins of the same uniform character seem to have circulated throughout the empire, in Italy, the east and the west. There appears to be no distinctive features of portraiture, legend, lettering or bust truncation that distinguish finds from one part of the empire from those in another. The different forms of obverse legend mark succes-

| Romea | Pompeii (1812) b | Utrechtc | Corbridge d | Paris (1867) e | Italica f | Zirkowitz g | Mardinh | Liberchies i | Total | Approx. % | |

| Cat. | |||||||||||

| 22 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 26 | 7.5 |

| 23 | 2 | – | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 18 | 5.2 |

| 24 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 1 | – | – | 3 | 10 | 3 | 28 | 8.0 |

| 25 | 22 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 9 | 26 | 10 | 25 | 39 | 151 | 43.2 |

| 26 | 6 | – | 1 | – | – | – | 1 | – | 1 | 9 | 2.6 |

| 27 | 3 | 1 | – | – | – | – | 2 | 2 | – | 8 | 2.3 |

| 28 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 55 | 16.0 |

| 29 | – | – | 1 | – | – | 1 | 2 | – | 2 | 6 | 1.7 |

| 30 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | 1 | 9 | 2 | 27 | 7.7 |

| 31 | 1 | – | 1 | – | 1 | – | – | 3 | 5 | 11 | 3.2 |

| 32 | 2 | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | 1 | 4 | 1.2 |

| 33 | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3 | – | 5 | 1.4 |

| Total | 66 | 18 | 24 | 10 | 20 | 45 | 31 | 67 | 67 | 348 |

| Reka-Devnia a | Falkirkb | V alenic | Frondenberg d | Total | Approx. % | |

| Cat. | ||||||

| 54 | 3 | 1 | 1 | — | 5 | 2.5 |

| 55 | 3 | — | — | 2 | 5 | 2.5 |

| 56 | — | — | 1 | — | 1 | 0.5 |

| 57 | 23 | 7 | 18 | 3 | 51 | 25.5 |

| 58 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 59 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 9 | 4.5 |

| 60 | 39 | 4 | 12 | 4 | 59 | 29.5 |

| 61 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 15 | 7.5 |

| 62 | 15 | 4 | — | 1 | 20 | 10.0 |

| 63 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 64 | 2 | 2 | — | — | 4 | 2.0 |

| 65 | — | 1 | 4 | — | 5 | 2.5 |

| 66 | — | — | 3 | 2 | 5 | 2.5 |

| 67 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 68 | 4 | 2 | 7 | — | 13 | 6.5 |

| 69 | 5 | 1 | 2 | — | 8 | 4.0 |

| Total | 102 | 27 | 55 | 16 | 200 |

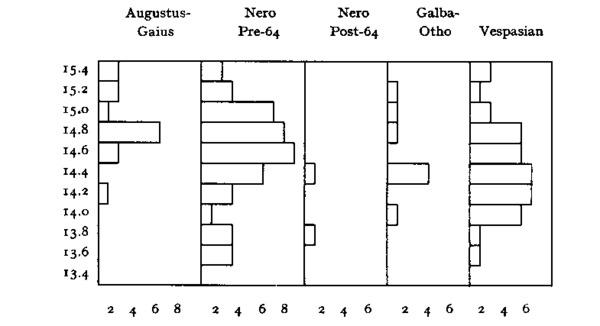

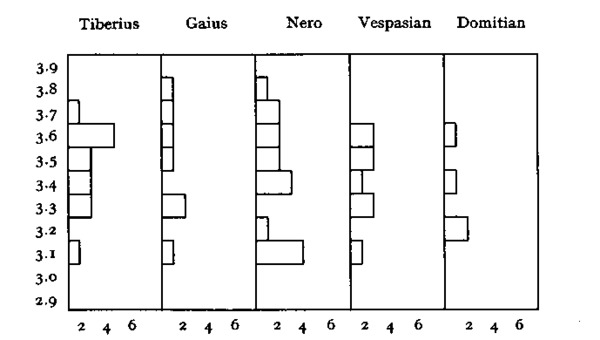

This gold and silver coinage forms a remarkably compact group, and the portrait imagines used by its die engravers are basically the same as those used for the aes of the mint of Rome. The bust truncation of aurei and denarii dated TRP IX and TRP X (Plate I, 19-20) is very close to that of the Roman aes without SC (Plates V–VI, 177ff.); the truncation of the early undated gold and silver (Plate I, 22, 23) is close to that on the Roman aes with SC struck in 64–66 (Plate VII, 200, 205); and the truncation of the gold and silver with the praenomen IMP (Plate II, 31, 65, 66) is very similar to that of Roman aes with the praenomen IMP (Plate IX, 238, 240). None of these has anything in common with the characteristic Lugdunum truncation at any stage (Plate XIII, 419ff.). The common form of bust truncation seems to have been an external factor derived from common imagines used by all the engravers at a mint. The use of common imagines shared with the Roman aes clearly points to Rome rather than Lugdunum as the place of the gold and silver die engraving establishment. 5

There is good evidence for the existence of the mint at Rome in the senatorial office of the tresviri monetales aere argento auro fiando feriundo, which is found on inscriptions down to third century a.d., 6 and in the series of mint inscriptions from Rome. 7

Rome would certainly have been the most convenient minting place for gold and silver under Nero. The chief sources for freshly mined gold and silver were the mines in the Iberian peninsula, 8 especially those in northwest Spain which were imperial property 9 at this period. The large revenue from these imperial mines would no doubt usually be turned into precious coin to meet imperial expenditure. The principal items of expenditure would be central state administration, public works and buildings, doles, donatives, the army and provincial government. The financial arrangements, however, did not repeatedly involve the transportation of large sums of money. Each province seems to have had its own provincial treasury and only the surpluses or deficits would be transferred at the end of each accounting period. 10 Apart from the maintenance of the frontier armies, the heaviest recurrent expenses, not counterbalanced by comparable local sources of revenue, must have been those for imperial activities at Rome. These were often costly 11 and Italy alone of the provinces was exempt from direct taxation. 12 Most of the precious metal coins struck from bullion stocks must have been put into circulation at Rome as payments of this kind, even though the coins may have passed through commercial channels almost immediately to various parts of the empire to settle trade accounts for imports to the capital. 13

It is of course theoretically possible that, even though the gold and silver dies were engraved centrally, and the major part of the precious coinage was struck in Rome, some aurei and denarii may have been struck at branch mints. 14 But there is no clear evidence to support such a hypothesis. The Vichy inscription 15 mentioning a soldier of cohors XVII Lugdunensis ad monetam, attributed to the time of Claudius or Nero, can quite well refer to the aes mint which continued to function at Lugdunum under the Flavians. 16 There is no need to refer it to the continued presence of the gold and silver mint, known to be at Lugdunum in a.d. 18. 17 Nor do finds of ancient dies support the hypothesis of subordinate mints. Only three such finds of dies are known for Nero. 18 One in the Museum at Arlon, found locally, is certainly the product of an ancient forger, as it is a metal mould for casting 44 denarii at a time. The other two, both in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, are obverse dies for aurei or denarii. One was "probably found in France" and the other is "said to have been found in France c. 1816," but both may very well have been used by ancient forgers. Many plated denarii are known for Nero as for all the other early emperors. 19 Most of them are in good style and some have argued that they may have been produced by official mint(s) as a measure of illicit profit for the government. 20 But whatever one's verdict on plated denarii of Claudius and earlier emperors, it is now clear that Nero's plated silver was the product of unofficial forgers. The analysis of Nero's coinages has closely defined the issues of denarii and the obverse and reverse types used in each issue. Had the plated denarii been produced under official auspices they would undoubtedly have been made in the same mint organization with the same combinations of types as the regular denarii in good silver. But whereas hybrids between issues do not occur on good denarii, they are comparatively common within the plated group, combining not only the obverse and reverse types of different issues, but sometimes even obverse and reverse types of different emperors. Whether the dies for these plated denarii were illegally appropriated from an official mint, or whether they were the work of competent private engravers, 21 there can be little doubt that the manufacture of plated denarii was the work of forgers. The places at which finds of early imperial dies have been discovered are singularly out of the way. 22 None has been found in Rome or Lyons, the two known mint cities of the early empire. Nor have any been found in other places where one would expect there to be branch mints (if such were the organization)—towns such as Trier, Arles, Amiens, London—the central location of which commended them as mint cities in the widely changed conditions of the late empire. There is nothing to show that the coins struck from these dies were made under official auspices in the localities where the dies were discovered. In only one case has it been shown that an impeccable coin was struck from one of these dies, 23 but even this die may well have fallen into the hands of forgers by appropriation from the mint after it had been used to strike official coins. And it seems most likely that the dies recovered from these scattered find spots were the property of ancient forgers.

| a |

Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica Communale di Roma

56 (1930), pp. 1ff.

|

| b |

Fiorelli, Pompeianarum Antiquitalum Historia. I.3, pp. 250–51.

|

| c |

Opgravingen op het dompe in te Utrecht, Haarlem 1934, pp. 49ff.

|

| d |

NC 1912, pp. 265–312.

|

| e |

Fonds Vacquer à la Bibliothèque de la ville de Paris. The late Mlle. Fabre kindly sent me details of this find.

|

| f |

NZ vol. 34, pp. 29ff.

|

| g |

Mitteilungen C. C. Steiermark 2, 173; 3, 157; 5, 109.

|

| h |

K. Regling, "Der Schatz römischer Goldmünzen von Diarbekir (Mardin)," BlM 1930–33, pp. 353–381.

|

| i |

M. Thirion, Le lrésor de Liherchies. Aurei des Ier et IIe sièdes (Brussels 1972).

|

| a |

N. A. Mouchmov, "Le trésor numismatique de Reka-Devnia", Annuaire du Musée National Bulgare 1934 Supplément.

|

| b |

NC 1934, pp. 1–30.

|

| c |

MSS. list in British Museum.

|

| d |

ZfN 1912, pp. 189–253.

|

| 1 |

Sydenham, Nero, pp. 132–169.

|

| 2 |

Sydenham, The Coinage of Caesarea in Cappadocia (London, 1933), pp. 36ff.

|

| 3 |

W. Wruck, Die syrische Provinzialprägung von Augustus bis Traian, (Stuttgart, 1931), pp. 63ff.

|

| 4 |

D. W. Mac Dowall, "Two Roman Countermarks of a.d. 68" NC 1960, pp. 103–112.

|

| 5 |

My argument is not open to the sort of objection that M. Grant makes ("The Mints of Roman Gold and Silver in the Early Principate,"

NC 1955, p. 44) to C. H. V. Sutherland's attribution of Claudius' gold and silver to Rome— "surely we cannot argue that certain gold and silver is of Rome because of a stylistic resemblance to aes which we believe to be Roman''—for it merely points to the existence of imagines of two distinct types and identifies the type used on the aurei and denarii.

|

| 6 |

F. Lenormant, La monnaie dans l'antiquité III (Paris, 1878), pp. 185ff.

|

| 7 |

CIL VI, 42, 43, 44, 239, 791, 1145, 1607, etc.

|

| 8 | |

| 9 |

Frank, Survey III, pp. 166ff.

|

| 10 |

Cf. A. H. M. Jones, "The Aerarium and the Fiscus," J RS 1950, pp. 22–29. In this discussion I use the generic term "treasury" to cover the activities of both aerarium and fiscus.

|

| 11 |

Nero's building operations were extensive (see Platner and Ashby, A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient

Rome (London, 1929), p. 595; Nero spent heavily on games, donatives, gifts, etc. Suetonius, Nero, 10.1; 11; 30; Tacitus, Annals 12.58.

|

| 12 | |

| 13 |

The capital had a permanently adverse balance of trade. Cf. Frank, Survey V (1940), pp. 281–82.

|

| 14 |

A suggestion made by Sutherland in a review of H. R. W. Smith, Problems Historical and Numismatic in the Reign of

Augustus (Berkeley, 1951) in NC 1952, p. 145. Cf. M. Grant

NC 1955, pp. 53–54.

|

| 15 |

CIL XIII, 1499, and Mommsen, Hermes 16 (1881), p. 645.

|

| 16 | |

| 17 |

Strabo 4.3.2. C 192.

|

| 18 |

C. C. Vermeule, Some Notes on Ancient Dies and Coining Methods (London, 1954), pp. 29–30.

|

| 19 |

For plated denarii of Nero see pp. 35 and 243 below.

|

| 20 |

L. A. Lawrence, "On Roman Plated Coins," NC 1940, p. 194, believed that we should regard plated coins as part of the governmental issues, and so apparently does Sutherland,

Coinage in Roman Imperial Policy, p. 201; but Mattingly BMCRE I, p. xlivf., is doubtful about their official origin. Sydenham, "On Roman Plated Coins," NC 1940, pp. 2ooff., thought the St. Swithin's Lane hoard was the product of a forger but that plated denarii were also produced

by the mint. But M. H. Crawford's article "Plated Coins— False Coins," NC 1968, pp. 55–59, argues convincingly against this, and shows that except in irregular coinages produced in periods of civil

war, plated coins must have been forgeries.

|

The western aes of Nero falls into two basic types. 24 The first is characterized by a small globe at the point of Nero's bust on the obverse, and a characteristic M form of bust truncation (see Plates XIII, 432; XIV, 452). The style of portraiture of this group is quite distinctive and the varieties of obverse legend and reverse types, established by an analysis of well preserved coins with the globe (see Cat. 401–633), constitute an objective basis for attribution to this group even when the globe and form of bust truncation are not visible on worn or corroded coins.

The second type has no globe and a straighter form of bust termination (see Plate II, 71, 74). The style of portraiture is again distinct, and the analysis of well preserved coins enables us to establish the distinctive forms of obverse legends and reverse types that characterize this group (see Cat. 70–335).

The distribution of these two types in the years immediately after their issue is the basic evidence for the localization of the mints at which the two types were struck. It is not however sufficient merely to list the localities at which examples of each type are said to have been found, as this can sometimes obscure the original pattern of distribution. Single coins may have been lost at any time during the period of their continued circulation; and unusual types are liable to attract attention because they are unusual, whereas the ordinary pass unnoticed. It is therefore important to distinguish the quality of different categories of evidence, and to determine the general character of circulation in an area from the recurrent statistical pattern observed at a number of localities.

The best evidence consists of finds which accurately reflect currency circulating at a known point of time, because they can be given a secure terminus ante quem . 25 But there are comparatively few commercial hoards and stratified or closed sites which meet these rigorous canons. The next best evidence consists of the accumulated finds from a thoroughly excavated site, or the accumulated deposits recovered from a well or river bed. Such coins may have been lost at any time during their continued circulation, but it is a reasonable inference that the commonest types will have been most commonly lost; and where the finds from a site are sufficiently numerous, they should provide a reasonably accurate statistical pattern of circulation.

For regions where this quality of evidence is not available, some idea of distribution may be found by noting casual finds recorded in archaeological publications or noted in local museums. The cumulative totals of such finds may be less reliable statistically, if there has been any preference in acquiring or noting specimens of new and rare varieties or in declining badly preserved specimens of common types. Finally, in the absence of other evidence, it is often possible to form an approximate estimate of circulation from the un- provenanced collections of local museums. The general character of some collections suggests quite strongly that it is largely composed of local finds even though the museum has not kept accurate records, but such evidence must be used with great care.

So that appropriate weight can be given to each category of evidence, finds in the following paragraphs have been classified as:

A—A hoard or excavation finds with terminus ante quem of a.d. 80 or before.

B—The aggregate of coins from other excavations or deposits.

C—Casual finds.

D—Unprovenanced coins probably found locally.

For localities where there is adequate evidence from finds classified A and B, finds of other categories which cannot contribute anything further to the picture of distribution have not been cited. Where it is necessary to cite casual finds, the evidence of groups of coins which have greater statistical validity has been preferred to that of single finds.

Finds of sestertii, dupondii and asses in Britain, Upper and Lower Germany, Belgica, Lugdunensis and Raetia are almost all of the "globe" type; finds from Narbonensis are predominantly of the "globe" type; finds from Spain, Noricum, Pannonia and the area east of the Rhine and north of the Danube are divided between the "globe" and the "non-globe" type; and finds from Italy are almost all of the "non-globe" type. In the following list, coins are attributed to the "globe" and "non-globe" mint on the basis of the criteria set out in this monograph. By analyzing the varieties of coins in good condition it is possible to establish those forms of obverse legend and reverse type found exclusively at the "globe" mint, those found exclusively at the "non-globe" mint and those which occur at both mints. These criteria enable us to attribute many find coins to the appropriate mint, even when globe, aegis or bust truncation may not be visible.

This section is intended merely to indicate the pattern of circulation for each locality—not to constitute an exhaustive list of finds. It would be possible to add further entries for many localities, but they could hardly affect very significantly the overall picture.

| GLOBE TYPE | NON-GLOBE TYPE | ||||||

| Sest. | Dup. | As | Sest. | Dup. | As | ||

| Britannia | |||||||

| A | Southwark hoard 26 | — | 2 | 9 | — | — | — |

| B | Richborough exc. 27 | — | 5 | 71 | — | 2 | — |

| B | Silchester exc. 28 | — | 2 | 9 | — | — | — |

| B | Wroxeter exc. 29 | — | 2 | 8 | — | 1 | 1 |

| B | Leicester exc. 30 | — | 2 | 9 | — | — | — |

| B | St. Albans exc. 31 | 1 | 2 | 12 | — | — | — |

| B | R. Thames deposit. 32 | 2 | 5 | 9 | — | — | — |

| B | R. Churn deposit 33 | — | 2 | 4 | — | — | — |

| B | R. Walbrook, London 34 | 1 | 3 | 8 | — | — | — |

| Germania Inferior | |||||||

| B | Nijmegen 35 | 9 | 11 | 13 | 1 | — | 1 |

| B | Neuß exc. 36 | 15 | 17 | 37 | — | 2 | 1 |

| B | Ziegeleien bei Neuß 37 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | — | — |

| GLOBE TYPE | NON-GLOBE TYPE | ||||||

| Sest. | Dup. | As | Sest. | Dup. | As | ||

| B | Bonn exc. 38 | 2 | 3 | 3 | — | — | — |

| B | Vetera exc. 39 | 9 | 8 | 10 | — | — | — |

| Germania Superior | |||||||

| B | Mainz exc. 40 | — | 2 | 7 | — | — | — |

| B | Vindonissa exc. 41 | 9 | 22 | 103 | 1 | 4 | 10 |

| C | Marburg bei Pommern 42 | — | 2 | 8 | — | — | — |

| Belgica | |||||||

| B | R. Sambre deposit 43 | — | — | 3 | — | — | — |

| B | Condé-sur-Aisne 44 | — | 77 | 656 | — | 9 | 199 |

| C | Compiègne 45 | — | — | 13 | — | — | 2 |

| C | Besançon 46 | — | — | 15 | — | — | 4 |

| C | Franche Comté 47 | — | — | 7 | — | — | 2 |

| C | Héraple 48 | — | — | 4 | — | — | 2 |

| C | Sarrebourg 49 | — | — | 4 | — | — | — |

| C | Langres 50 | — | — | 4 | — | — | — |

| Lugdunensis | |||||||

| A | Sens hoard 51 | — | — | 3 | — | 1 | 1 |

| A | Augers en Brie 52 | — | 1 | 6 | — | — | — |

| GLOBE TYPE | NON-GLOBE TYPE | ||||||

| Sest. | Dup. | As | Sest. | Dup. | As | ||

| B | R. Mayenne 53 | 3 | 97 | 707 | — | 10 | 111 |

| C | Rouen 54 | — | — | 3 | — | — | — |

| C | Forêt de la Lande 55 | — | — | 6 | — | — | 2 |

| D | Lyons 56 | — | — | 2 | — | — | — |

| Aquitania | |||||||

| A | Puy de Dôme hoard 57 | — | — | 45 | — | — | 6 |

| C | Bard (Auvergne) 58 | — | — | 1 | — | — | — |

| D | Saintes 59 | — | — | 7 | — | — | 4 |

| D | Poitiers 60 | — | — | 17 | — | — | 3 |

| Narbonensis | |||||||

| B | Orange 61 | — | — | 2 | — | — | 1 |

| C | Vaison 62 | — | — | 3 | — | — | 2 |

| C | St. Remy 63 | — | — | 5 | — | — | — |

| C | Basses Alpes 64 | — | — | 4 | — | — | — |

| D | Vienne 65 | 2 | 3 | 9 | 4 | — | 3 |

| D | Nîmes 66 | 10 | 3 | 27 | 7 | 4 | 11 |

| GLOBE TYPE | NON-GLOBE TYPE | ||||||

| Sest. | Dup. | As | Sest. | Dup. | As | ||

| D | Toulon 67 | — | — | 3 | — | — | 3 |

| D | Valence 68 | — | — | 4 | — | — | 1 |

| Raetia | |||||||

| C | Augsburg 69 | — | — | 15 | — | — | 5 |

| C | Augsburg 70 | 1 | 2 | 5 | — | — | 3 |

| C | Kempten 71 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 1 | — | 4 |

| C | Mertingen 72 | — | — | 5 | — | — | — |

| C | Aislingen 73 | — | 2 | 1 | — | — | 1 |

| C | Burghöfe 74 | 1 | — | 4 | — | — | — |

| C | Bregenz 75 | — | — | 2 | — | — | — |

| Noricum | |||||||

| C | Virunum 76 | — | — | 1 | — | — | — |

| C | Maria Saal 77 | — | — | 1 | — | — | — |

| C | Frauenberg bei Leibnitz 78 | — | — | 1 | — | — | — |

| C | Wagna 79 | — | 1 | 1 | — | — | 4 |

| D | Enns 80 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | — | 1 |

| Pannonia | |||||||

| B | Carnuntum 81 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | — | 4 |

| B | Carnuntum 82 | — | 2 | 1 | — | — | 1 |

| GLOBE TYPE | NON-GLOBE TYPE | ||||||

| Sest. | Dup. | As | Sest. | Dup. | As | ||

| C | Celje 83 | — | 1 | — | — | 1 | — |

| C | Zagreb 84 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| C | Ptuj 85 | 2 | 1 | 1 | — | — | 1 |

| Tarraconensis | |||||||

| C | Tarragona 86 | — | 1 | — | — | — | — |

| C | Lezuza 87 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| C | Zaragoza 88 | 3 | 2 | 2 | — | — | 1 |

| C | Menorca 89 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| C | Segorbe 90 | — | — | — | — | — | 1 |

| C | San Sebastian Prov. 91 | — | 1 | 1 | — | 1 | 1 |

| C | Valencia 92 | — | — | — | — | 2 | 2 |

| C | Pollensa 93 | — | — | — | — | — | 1 |

| D | Tarragona 94 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 1 | — | 3 |

| D | Madrid 95 | 96 | 47 | 55 | 89 | 40 | 91 |

| Lusitania | |||||||

| B | Merida 96 | 1 | 2 | — | — | — | — |

| C | Merida 97 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| D | Lisbon 98 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 9 |

| GLOBE TYPE | NON-GLOBE TYPE | ||||||

| Sest. | Dup. | As | Sest. | Dup. | As | ||

| D | Porto 99 | 2 | 1 | — | — | — | 7 |

| D | Porto 100 | 1 | — | 2 | 1 | — | 11 |

| Germania (East of Rhine and North of Danube) | |||||||

| B | Hofheim 101 | — | 1 | 2 | — | — | 1 |

| B | Saalburg 102 | — | 1 | 2 | — | — | — |

| C | Rheinbrohl 103 | — | — | 1 | — | — | 1 |

| C | Wiesbaden 104 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 1 | — | — |

| C | Heddernheim 105 | — | 1 | 4 | — | — | 3 |

| C | Huffingen 106 | — | 2 | 8 | — | — | — |

| C | Waldkirch 107 | — | — | 1 | — | — | 1 |

| B | Ems 108 | — | — | 2 | — | — | — |

| C | Kasteli Zugmantel 109 | — | — | 1 | — | 1 | — |

| B | Kasteli Obernburg 110 | — | — | 1 | — | — | 2 |

| C | Riegel 111 | — | 4 | — | 1 | — | — |

| Italia | |||||||

| A | N. Italian hoard 112 | — | — | — | 5 | — | — |

| A | Pozzarello hoard 113 | — | — | 3 | 17 | 9 | 74 |

| GLOBE TYPE | NON-GLOBE TYPE | ||||||

| Sest. | Dup. | As | Sest. | Dup. | As | ||

| A | Pompeii 114 | — | — | 3 | 14 | 6 | 46 |

| A | Pompeii 115 | — | — | 3 | — | — | 178 |

| A | Pompeii 116 | — | — | — | 68 | 2 | — |

| B | Tiber 117 | 2 | — | 11 | 21 | 3 | 218 |

| B | Ostia 118 | — | — | — | — | 6 | |

| B | Minturnae 119 | — | — | — | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| C | Rome 120 | — | — | 1 | — | — | 23 |

| B | Aquileia 121 | 7 | 7 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 20 |

| B | Liri 122 | — | 1 | — | 43 | 3 | 20 |

| 21 |

Crawford, "Plated Coins," pp. 56–57, shows that a plated Republican denarius in Hannover was struck from dies, mechanically

copied from a pure silver coin.

|

| 22 |

Vermeule, Ancient Dies, pp. 29–30.

|

| 23 |

RN 1946, "Procès Verbaux," pp. ii–viii, though of course others too may have been "official" dies.

|

| 24 |

BMCRE I, p. clxiiif.

|

| 25 |

Cf. J. G. Milne, "The Interpretation of Coin-finds" Finds of Greek Coins in the

British

Isles (London, 1948), pp. 15–16; cf. also Greek and Roman Coins and the Study of History (London, 1939), pp. 95–96.

|

| 26 |

NC 1903, pp. 99–102.

|

| 27 |

Totals from Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of A ntiquaries of London

, Nos. 6, 7, 10 and 16.

|

| 28 |

Now in Reading Museum.

|

| 29 |

Now in Rowley's House Museum, Shrewsbury.

|

| 30 |

Rep ResCommSocAntLond, no. 15.

|

| 31 |

Rep ResCommSocAntLond, no. 11.

|

| 32 |

NC 1841–42, pp. 147–168. The figures are for those coins now in the British Museum.

|

| 33 |

NC 1864, pp. 216–23.

|

| 34 |

Ant J 1962, pp. 40–41.

|

| 35 |

Local finds in Rijksmuseum G. M. Kam, Nijmegen.

|

| 36 |

BonnerJb 1904, pp. 263–67, and now republished by H. Chantraine in Novaesium III Die antiken Fundmünzen der Ausgrabungen in Neuss (Berlin, 1968).

|

| 37 |

Bon ner Jb 1904, p. 450.

|

| 38 |

Information from Wilhelmina Hagen.

|

| 39 |

Information from Wilhelmina Hagen.

|

| 40 |

MainzerZ 1911, pp. 71–72; 1912, p. 84; 1913–14, p. 66; 1918, p. 25; 1929, pp. 66f.

|

| 41 |

C. M. Kraay, Die Münzfunde von Vindonissa (Basel, 1962).

|

| 42 |

Bonner Jb 1897, pp. 89–91.

|

| 43 |

RBN 1956, pp. 55–80.

|

| 44 |

RN 1969, pp. 76–130.

|

| 45 |

St. Germain-en-Laye Musée.

|

| 46 |

Musée de Besançon. I am indebted to Lucien Lerat and Yves Jeannin for giving me detailed information about the coins in the

Besançon Museum and their provenances.

|

| 47 |

Musée de Besançon.

|

| 48 |

J ahrbuch der Gesellschaft für lothringische Geschichte 1894, p. 322.

|

| 49 |

J bGeslothGesch 1899, p. 326.

|

| 50 |

Musée de Besançon.

|

| 51 |

Bulletin de la Société Archéologique de Sens 21 (1905), pp. 235–49.

|

| 52 |

NC 1967, pp. 43–46.

|

| 53 |

Bulletin de la Société d'Archéologie, Sciences, Arts et Belles-lettres de la Mayenne, 1865, pp. 9ff, 32–36. Through the kindness of M. Bisson I have been allowed to study the unpublished part of this large

deposit.

|

| 54 |

Musée Départmental, Rouen.

|

| 55 |

Musée Départmental, Rouen.

|

| 56 |

Seen by M. Grant in trade, cf. NC 1955, pp. 21–37.

|

| 57 |

Cf. P. F. Fournier "Les travaux de 1956 au sommet du Puy de Dôme," Bulletin Historique et Scientifique de l'Auvergne 1956, pp. 196–201. Through the kindness of the late Mlle Fabre of the Bibliothèque Nationale, I have been permitted to examine

this hoard, which has now been published by J. B. Giard, RN 1964, pp. 151–57.

|

| 58 |

P. F. Fournier, Bulletin Historique et Scientifique de l'Auvergne 1939, p. 3.

|

| 59 |

Hôtel de Ville, Saintes.

|

| 60 |

Le Musée, Poitiers.

|

| 61 |

Orange Musée from excavations in the theatre.

|

| 62 |

J. Sautel, Vaison dans l'antiquite II (Avignon, 1926), pp. 78–79.

|

| 63 |

St. Remy-en-Provence Musée from Glanum, and H. Rolland, Fouilles de Glanum.—Gallia Suppl. 1 (Paris, 1946), p. 23.

|

| 64 |

Musée des Antiquités Nationale, St. Germain-en-Laye.

|

| 65 |

Vienne Musée.

|

| 66 |

Formerly in Maison Carrée, Nîmes.

|

| 67 |

Seen by M. Grant in trade, Toulon.

|

| 68 |

La Bibliothèque, Valence.

|

| 69 |

Münzkabinett, Munich.

|

| 70 |

Die Fundmünzen der Römischen Zeit in Deutschland 1962 (FMRD) I.7. Schwaben 7001.

|

| 71 |

FMRD I.7. Schwaben 7182.

|

| 72 |

H.-J. Kellner, Die römischen Fundmünzen auf dem nördlichen Teil von Rätien.

|

| 73 |

FMRD I.7. Schwaben 7044.

|

| 74 |

FMRD I.7. Schwaben 7069.

|

| 75 |

Vorarlberger Landesmuseum, Bregenz.

|

| 76 |

Landesmuseum für Kärnten, Klagenfurt.

|

| 77 |

Fundberichte aus Österreich II, p. 296.

|

| 78 |

F. Pichler, Repertorium der steierischen Münzkunde II (Graz, 1867), p. 12.

|

| 79 |

Pichler, Repertorium II, pp. 12, 14–15.

|

| 80 |

Museum Lauriacum, Enns.

|

| 81 |

Museum Carnuntinum, Bad Deutsch Altenberg.

|

| 82 |

Sammlung Ludwigsdorff.

|

| 83 |

Pichler, Repertorium II, pp. 13–14.

|

| 84 |

Šime Ljubić, Popis Arkeologičkoga Odjela Nar. Zem. Muzeja u Zagrebu, pp. 132ff.

|

| 85 |

Pichler, Repertorium II, pp. 12–15.

|

| 86 |

1925/30 excavations in Forum, now in Museo Arqueológico, Tarragona.

|

| 87 |

Bolletino Arqueológico del Sudeste Español 2 (1945), p. 204.

|

| 88 |

Museo Arqueológico, Zaragoza.

|

| 89 |

Felipe Mateu y Llopis, "Hallazgos Monetarios XII," No. 752, NumHisp 1955, pp. 130–31.

|

| 90 |

Mateu y Llopis, "Hallazgos Monetarios XII," No. 794, NumHisp 1955, p. 137.

|

| 91 |

Private coll., Santander.

|

| 92 |

Private coll., Santander.

|

| 93 |

Mateu y Llopis, "Hallazgos Monetarios VII," No. 600, NumHisp 1952, pp. 253–54.

|

| 94 |

Museo Arqueológico Provincial, Tarragona.

|

| 95 |

Museo Arqueológico Nacional, Madrid.

|

| 96 |

Museo Arqueológico, Merida.

|

| 97 |

Now in Museo Arqueológico, Cordoba.

|

| 98 |

Casa da Moeda, Lisbon.

|

| 99 |

Museu Nacional de Soares dos Reis, Porto.

|

| 100 |

Private coll., Porto.

|

| 101 |

Annalen des Vereins für Nassauische A Itertumskunde 34 (1904), p. 27.

|

| 102 |

L. Jacoby, Das Römerkastell Saalburg bei Homburg, pp. 365ff.

|

| 103 |

Information from Wilhelmina Hagen.

|

| 104 |

AnnVerNassauAltertumskunde 26 (1896) and 37 (1907), pp. 4ff.

|

| 105 |

Mitteilungen über römische Funde in Heddernheim 3 (Frankfurt am Main, 1900), pp. 10–61 and 4 (1907), p. 54.

|

| 106 |

. Revellio, "Das Kasteli Hüfingen," Der Obergermanisch-Rätische Limes 55 (Berlin/Leipzig, 1937), pp. 33–34.

|

| 107 |

K. Bissinger, Funde römischer Münzen im Großherzogtum Baden 1 (Donaueschingen, 1887), p. 14, 35.

|

| 108 |

R. Bodewig, "Das Kasteli Ems," Der Obergermanisch-Rätische Limes 36 (1937), p. 22.

|

| 109 |

L. Jacoby, "Das Kasteli Zugmantel," Der Obergermanisch-Rätische Limes 32 (Heidelberg, 1909).

|

| 110 |

A. D. Conrady, "Das Kasteli Obernburg." Der Obergermanisch-Rätische Limes 18 (Heidelberg, 1903).

|

| 111 |

Bissinger, Baden, pp. 15–16 and (2nd ed. Karlsruhe, 1906), 98, p. 9.

|

| 112 |

Seen in trade by the author.

|

| 113 |

Mélanges d'archéologie et d'histoire 1964, pp. 51–90.

|

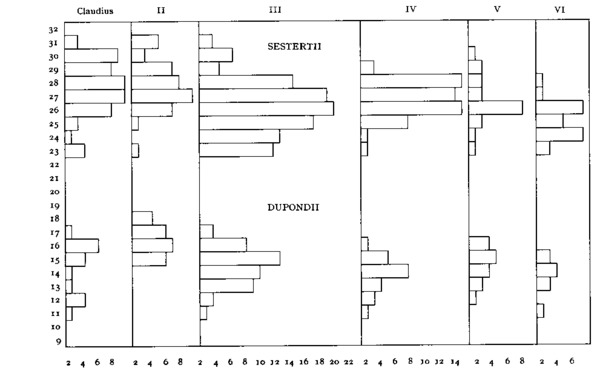

Nero's aes consisted of asses, semisses and quadrantes in copper, and of sestertii and dupondii in orichalcum, with a limited issue of asses, semisses and quadrantes also in orichalcum. Orichalcum was originally a natural alloy, but by the middle of the first century a.d. the Romans made the alloy artificially by heating copper in a bed of calamine. The raw materials needed for the aes coinages were thus ordinary copper, copper suitable for processing into orichalcum, and calamine needed for the processing.

The principal sources for copper in the middle of the first century a.d. were the imperial mines in Spain and Cyprus. 123 In Spain the mines of Sextus Marius had been confiscated by Tiberius;124 and the Hadrianic letter to Ulpius Aelianus 125 read in conjunction with the Lex Metalli Vipascensis 126 shows clearly that the copper, silver and iron mines in established mining districts of Spain were state owned at that period; and its reference to a forma revised by Hadrian shows that the original of this lex must have been of earlier date. In Cyprus the mines seem to have been nationalized when the tribune Clodius annexed the island in 58 b.c.; 127 Augustus gave Herod a concession but retained a half interest for the Roman government; 128 and the mines near Soli were still under state ownership when Galen visited them in the second century a.d. 129

Spanish copper, called "Marianum" or "Cordubense," was especially important for the coinage, as it readily absorbed calamine and reproduced the excellence of orichalcum in making sestertii and dupondii. 130 The extensive copper workings in Cyprus were apparently less highly valued once better copper (and orichalcum) had been found in other countries, but Pliny explicitly tells us that Cypriot copper was used for the production of asses. 131

There do not seem to have been any other important copper workings in the Roman Empire at this period. The copper from Livia's mine in Gaul had enjoyed a high reputation but the supply soon gave out; 132 Sallustius' copper from Haute-Savoie was highly esteemed "next to orichalcum," but supplies only lasted for a short time; 133 and although there were also Roman copper mines near Lyons the evidence for their working is of third century date. 134 Southeast Britain had used imported copper at the time of Caesar's invasion, 135 and although copper was worked further north during the Roman occupation at Plynlimmon, the Gt. Ormes Head, Anglesy, Caernarvon and in the Dee Valley, 136 these forward areas were not under secure Roman control during Nero's principate and can hardly have been sources for the copper required by the mint. Workings of copper in Upper and Lower Germany were neither profitable nor extensive during the first century. There was prospecting of early imperial date in the poor impregnations of azurite and malachite at Blauberg in the Saar and at Kerdel; 137 but the copper workings in the ancient mines at the mouth of the Ems 138 lay beyond Roman territory under Nero. Illyria provides hardly any evidence of Roman mining and Dacia was outside Roman control at this period. There were extensive ancient copper workings at Majdanpek in the mountains of Moesia, but Davies has shown that the mines were abandoned when the Romans consolidated the Danube bank. 139

The principal sources of calamine, the second mineral required in the production of orichalcum, 140 are also mentioned by Pliny. It came from overseas, was formerly also found in Campania and now in the territory of Bergamo. "It is also reported to have been recently discovered in the province of Germany," 141 a reference to the important mine at Stollberg which subsequently became the principal center of bronze production in the Empire. 142 These deposits were discovered some time between a.d. 57 and 77. 143

| 114 |

Pompeii Antiquarium.

|

| 115 |

RIN 1897, p. 272.

|

| 116 |

From a group of coins in the Museo Nazionale, Naples.

|

| 117 |

Now in Muzeo Nazionale delle Terme, Rome.

|

| 118 |

Ostia Museum.

|

| 119 |

J. Johnson, Excavations at Minturnae 1 (Philadelphia, 1935), p. 99.

|

| 120 |

Museo Capitolino, Rome, believed to have been found in the city.

|

| 121 |

Museo Archeologico, Aquileia.

|

| 122 |

NC 1970, pp. 96–97 and NC 1974, pp. 42–52.

|

| 123 |

O. Davies, Roman Mines in Europe (Oxford, 1935), p. 60; and R. J. Forbes, Metallurgy in Antiquity (Leiden, 1950), pp. 272 ff. The ancients do not generally seem to have realized the metallic qualities of zinc, and apparently

regarded the process as one which purified and strengthened the metal: cf. Davies Mines, Isidore, Etym. 16. 20.3. A detailed explanation of the manufacture of orichalcum in Roman times is given in Earle R. Caley, Orichalcum and Related Ancient Alloys, ANSNNM 151 (New York, 1964), pp. 92ff.

|

| 124 |

Davies, Mines, pp. 94 ff.

|

| 125 |

Tacitus, Annals vi, 19.

|

| 126 |

C. G. Bruns, Fontes iuris romani antiqui (7th rev. ed. Tübingen, 1909), pp. 289–93. See also discussion of these documents in Frank, Survey III, pp. 167–74.

|

| 127 |

Dio 38.30.5.

|

| 128 |

Josephus, Antiquities 16.5.5.

|

| 129 |

Galen 9.214.

|

| 130 |

Pliny, NH 34.1.2: "Summa gloria nunc in Marianum conversa, quod et Cordubense dicitur. Hoc a Liviano cadmeam maxime sorbet et aurichalci

bonitatem imitatur in sestertiis dupondiariisque."

|

| 131 |

Pliny, NH 34.2: "Cyprio suo assibus contentis."

|

| 132 |

Pliny, NH 34.1.

|

| 133 |

Pliny, NH 34.1.

|

| 134 |

CIL XIII, 2901.

|

| 135 | |

| 136 |

Davies, Mines, pp. 155ff.

|

| 137 |

Davies, Mines, pp. 177–78; the inscription CIL XIII, 4238 was found at Blauberg.

|

| 138 |

Davies, Mines, pp. 179f.

|

| 139 |

Davies, Mines, pp. 218ff.

|

| 140 |

Cf. note 131 above.

|

| 141 |

Pliny, NH 34.2.2.

|

| 142 |

Willers, "Neue Untersuchungen über die römische Bronze-Industrie von Capua und von Niedergermanien," Jahrbuch des provinzialen Museums zu Hannover 1906–7, p. 64.

|

| 143 |

Willers dates the discovery between a.d. 57, when Pliny seems to have been in Upper Germany, and a.d. 74.

|

Aes of the non-globe type circulated almost exclusively in Italy. There is no reason to doubt that the mint which produced this coinage was in fact the mint of Rome, for which we have repeated authorities in the senatorial office of the tresviri monetales, which continues to be found on inscriptions down to the third century a.d., 144 and in the series of mint inscriptions from Rome. 145 The city was the obvious center for supplying coinage to Italy, and the vast urban population (estimated at a million at this period 146 ) must have created a major demand for small change. In so far as the mint used freshly mined metal, there is no reason to doubt Pliny's statement that it used copper from Cyprus for its asses, and copper from Corduba as the basic constituent for the orichalcum of its sestertii and dupondii, 147 the alloy itself being made by heating the copper in a bed of calamine which presumably came from the Bergamo deposits. 148

Aes of the globe type enjoyed an almost exclusive circulation in Gaul, Britain, the Rhine and Vindelicia south of the Danube, and must have been struck in one of these western provinces. The use of an important second mint in the west was fairly general imperial practice during the first century. Vespasian continued to use the same mint with the same globe and characteristic bust truncation for a fairly large group of aes which circulated primarily in the same western provinces. 149

Sydenham 150 and Laffranchi 151 have suggested that "westernstyle" groups can be distinguished among the Agrippa asses and Claudius' aes, although the detailed evidence of site finds has not yet been analyzed to settle finally whether or not their criteria are sound. 152 This mint seems to have been the successor to the mint at Lugdunum which issued the extensive Altar series up to the early years of Tiberius,153 a series which constituted the main currency of the Rhine frontier at the time, and again struck semisses of the Altar type under Claudius.154Lyons was in fact an eminently suitable place for a western aes mint, in a perfectly safe area yet conveniently situated to supply the small change needed by the frontier armies of the Rhine, Britain and Upper Danube, and equally accessible to the principal sources of copper.

Under Nero freshly mined copper for the globe type sestertii and dupondii in orichalcum would almost certainly come from Corduba; and from Spain again, or possibly from Cyprus, would come the freshly mined copper for the asses and semisses. The calamine needed to manufacture the copper into orichalcum may have come from Bergamo, but it is far more likely that it came from the newly discovered mines at Stollberg. Although Spain was an extremely important source for the freshly mined copper used for Nero's western aes, Nero's mint was certainly not situated there. We have seen above that finds of Nero's aes are not common in Spain and the Iberian peninsula was not exclusively or even predominantly provided with aes of Nero's globe type. For similar reasons the Danubian provinces also can be excluded, and neither Britain nor Africa had the central position required. Germany remains a possibility, but was not conveniently placed between the sources of freshly mined copper and some of the areas ultimately supplied, notably Raetia, West Gaul and the Rhone valley. Gaul on the other hand would have enjoyed the great advantage of centrality and Lyons, its capital, enjoyed that advantage par excellence. Lyons, as Strabo tells us, "commands Gaul like an acropolis." 155 It lies at the center of the river communications of the country and had been made the center of Agrippa's road system. It was conveniently near the Rhine-Danube reentrant and all the normal routes from South Spain to the Rhine, North and West Gaul, Britain and Raetia would part ways here. 156

Lyons, moreover, had a long tradition as a mint city. Antony had struck quinarii there as governor in 42/41 b.c., and signed them with the name of the town. 157 We have Strabo's explicit statement for the existence there of a mint for gold and silver under Tiberius.158 It was the mint which produced the extensive Altar series under Augustus and Tiberius and the commemorative Altar semisses struck under Claudius. 159 Its position as a mint city is further attested by several inscriptions from the immediate environs, 160 and by the presence of an urban cohort designated "ad monetam." 161 Under Tiberius, no doubt, the troops must have played an important part in the security arrangements for the minting of gold and silver at Lyons; but even after the striking of coinage in the precious metals was transferred to Rome, 162 Lyons remained the only city in the provinces, apart from Carthage, to be garrisoned by an urban cohort. Its presence was first mentioned by Tacitus in a.d. 21 when Acilius Aviola used it to check the revolt of the Andecavi. 163 Cohort XVIII formed the garrison in 69 164 and I Flavia Urbana took its place by 73. 165 This Lugdunum cohort was expressly called COH XVII LVGDVNENSIS AD MONETAM in the dedication to Lucius Fufius at Equestre, an inscription which cannot be dated before the time of Claudius because the cohort is XVII nor very much later because the man had no cognomen. 166 There is therefore good reason for attributing the globe type aes of the mid-first century to Lyons, and for regarding it as a successor to the important western aes coinage of the Altar series. 167

| 144 |

F. Lenormant, La monnaie III, pp. 185 ff.

|

| 145 |

CIL VI, 42, 43, 44, 239, 791, 1145, 1607 etc.

|

| 146 |

Frank, Survey V, p. 140.

|

| 147 |

Pliny, NH 34.1.2.

|

| 148 |

In "The Quality of Nero's Orichalchum,'' SM 1966, pp. 101-105, I have commented on the lower percentage of zinc in several of Nero's orichalcum coins of the non-globe

mint, and suggested that many of the coins at Rome were struck from secondary alloy derived from remelted old coins.

|

| 149 |

See BMC RE II, pp. lviii ff.

|

| 150 | |

| 151 |

L. Laffranchi, "La monetazione imperatoria e senatoria di Claudio 1º durante il Quadriennio 41–44 d.º Cr.º," RIN 1949, pp. 41–48, though Laffranchi there suggests that the western European mint may be in Spain.

|

| 152 |

S. Jameson, "The Date of the Asses of M. Agrippa," NC 1966, pp. 95–124, on the other hand, argues that all three groups of Agrippa asses that she distinguishes were struck in

Rome, but she does not support her argument with find evidence. The absence of countermarks from her group (a), and the presence

of countermarks localized in the western provinces on groups (b) and (c) suggests to me that these latter two groups may be

the product of a western mint.

|

| 153 |

RIC, p. 91, nos. 359–371.

|

| 154 |

RIC, p. 130, nos. 70–71.

|

| 155 |

Strabo iv.6.11. Cf. Ammianus Marcellinus xv.11.17.

|

| 156 |

M. P. Charlesworth, Trade-routes and Commerce of the Roman Empire (2nd ed. Cambridge, 1926), pp. 183ff. and 192ff. H. R. W. Smith's objections in Problems Historical and Numismatic of the Reign of

Augustus (Berkeley, 1951), pp. 161-174, it should be noted, were directed against the view that Lugdunum was the sole gold and silver mint in the early empire; he did not attempt to deny that Lugdunum was a mint, though he strove to weaken Strabo's apparently straightforward statement of contemporary fact. He emphasized

the difficulties in navigating the Rhone, but the numerous inscriptions of the companies of navigators of the Rhone and Arar

(in CIL XIII) greatly undermine the force of this point as do the extensive Roman quays along the river at Lyons (O. Brogan, Roman Gaul [London, 1953], p. 103) and the extensive quays of more modern date at places like Avignon. In any case Agrippa's road system

followed the line of the main river routes, and there were good roads up the Rhone valley.

|

| 157 | |

| 158 |

Strabo 4.3.2.

|

| 159 |

Sydenham, NC 1917, p. 86.

|

| 160 |

CIL XIII, 1499, 1810, 1820

|

| 161 |

CIL XIII, 1499.

|

| 162 |

See BMCRE I Intro., and Sutherland Coinage in Roman Imperial Policy. For my objections to M. F. Grant's point of view in NC 1955, pp. 39–54 see p. 12 above.

|

| 163 |

Tacitus, Annals iii.41.

|

| 164 |

Tacitus, Histories i.64.

|

| 165 |

CIL XII, 2601.

|

| 166 |

See Mommsen in Hermes 16 (1881), p. 645, n. 4.

|

| 167 |

For the first ten years of Nero's principate the gold and silver struck at Rome bore tribunician dates TRP to TRP X, which clearly differentiated successive issues. During the first tribunician year to December 55 three aureus and denarius types were issued—one commemorating the deification of Claudius, the second with heads of Nero and Agrippina facing (Plate I, 2) and the third with jugate busts of Nero and Agrippina (Plate I, 3).

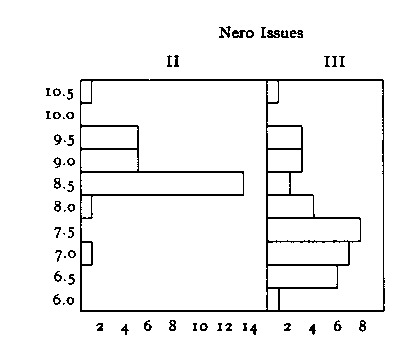

In TRP II a new obverse type was introduced (Plate 1, 4) which remained basically unchanged throughout the rest of the dated gold and silver coinage. Its legend was NERO CAESAR AVG IMP, and Nero's head was shown facing right with the hair drawn down over his forehead. During the course of these dated issues slightly older portraits of Nero were gradually substituted, and in the issue of the ninth tribunician year Nero's hair was shown for the first time raised in tiers above his forehead, the "in gradus formata" style described by Suetonius. 1 The reverse type of both the aurei and the denarii dated TRP II was EX SC within an oak wreath, the corona civica, and an outside legend PONTIF MAX TRP II PP completed Nero's titles from the obverse. In this year there was a rare issue of gold quinarii with the usual quinarius reverse type of Victoria. The aurei and denarii dated TRP III, III and V retained the same obverse and reverse types and merely altered the tribunician year in the reverse legend. All coins dated TRP VI included in their reverse legend COS IIII Nero's fourth consulship which began January 1, 60. 2

In the issues dated TRP VII three new reverse types of Virtus, Ceres and Roma (Plate 1, 11, 12, 13) were introduced to replace that of the Corona Civica. Coins of the new Virtus and Ceres types seem to be far commoner than either the old Corona Civica or the new Roma type in the issues of this year. 3 Indeed it is only when examples of the Corona Civica type and Roma type are taken together that their numbers equal those of either the Virtus or of the Ceres type dated TRP VII. It is interesting to note that the reverse legend of the Corona Civica type reads counterclockwise and so did that of the new Roma type, whereas the reverse legends of the Virtus and Ceres types read clockwise. This might possibly suggest that the new Virtus and Ceres types were introduced at the beginning of the year and struck alongside the Corona Civica types, and that the Roma type was introduced to replace the Corona Civica type later in the year. In the TRP VIII issue the three types of Virtus, Roma and Ceres were struck in both gold and silver; in the TRP VIIII issue all three types were again struck in gold, but Virtus and Roma alone in silver; in the TRP X issue only two types, Virtus and Roma, were struck, in both gold and silver. 4

Cat. 1–21, 35–53. Plate I.

| 1 |

Suetonius, Nero 51.

|

| 2 |

Degrassi, I fasti, p. 16.

|

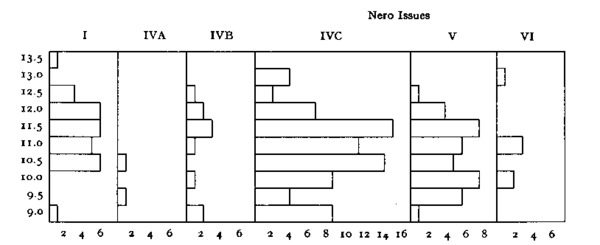

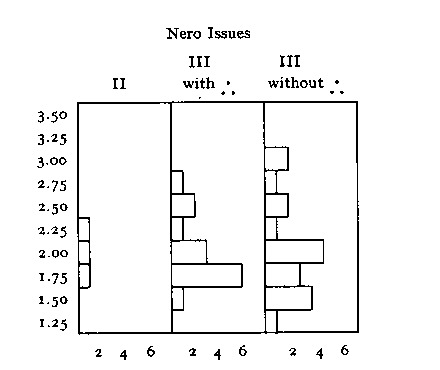

The undated gold and silver is a coinage struck on a reduced weight standard, on which the portraits are all later than on the dated series. The legends NERO CAESAR AVGVSTVS and NERO CAESAR, both of which lack the praenomen IMP, must belong to the period before mid-a.d. 66. No significant chronological distinction can however be drawn between these two forms. Except on plated denarii, NERO CAESAR was merely used with the AVGVSTVS GERMAN ICVS type on which the reverse legend completed the titulature from the obverse. After Nero assumed the praenomen IMP in mid-66 there were two forms of obverse legend on the gold and silver: IMP NERO CAESAR AVGVSTVS and IMP NERO CAESAR AVG PP. The reverse types in the issue with IMP NERO CAESAR AVGVSTVS were taken directly from, and must therefore have directly followed, the preceding issue with NERO CAESAR AVGVSTVS; but on denarii with IMP NERO CAESAR AVG PP in addition to the types that had been used with NERO CAESAR AVGVSTVS and IMP NERO CAESAR AVGVSTVS there were three new reverse types peculiar to the issue: the anepigraphic type of an eagle between two standards; and fresh varieties of the Roma and Salus types with the legends in the reverse field. IMP NERO CAESAR AVG PP must thus have been the latest form of reverse legend on Nero's gold and silver.

Issue 1 of the undated gold and silver coinage on the reformed standard had the obverse legends NERO CAESAR, and NERO CAESAR AVGVSTVS. In gold there were eight distinct reverse types: Augustus Germanicus; AugustusAugusta; Jupiter Custos; seated Roma; Salus; the Temple of Vesta; the Temple of Janus; and Concordia Augusta.

The first six of these types were regularly struck in silver too during this issue; but while the types of Janus temple and of Concordia Augusta are known in silver, they are extremely rare, are not represented in hoards, and were certainly not substantive denarius types. In this we seem to have evidence of an initial production of gold in two reverse types (accompanied by a token emission of silver) continuing the "two reverse type" pattern of the gold in TRP X, before the productive capacity was expanded. Among the other aurei and denarii with this obverse legend, the reverse types of Jupiter Custos and Salus are by far the commonest. These two subsequently became the sole substantive reverse types in issues 2 and 3 a, and it seems fairly certain that they continued to be struck in Issue 1, after the other reverse types were discontinued. We can therefore distinguish three phases within the issue:

1a. Janus and Concordia types, with substantive issues of aurei (but accompanied by a token issue of denarii).

1b. The six reverse types of Augustus Germanicus, AugustusAugusta, Jupiter Custos, Roma, Salus and Vesta with substantive issues in both gold and silver.

1c. The continuing issue of Jupiter Custos and Salus types in both gold and silver.

Cat. 22–29, 54–61, PLATES I–II.

Issue 2 had the obverse legend IMP NERO CAESAR AVGVSTVS. Its aurei were struck in two reverse types, Jupiter Custos and Salus, both of which were taken over directly from the preceding issue. Besides these two types of Jupiter Custos and Salus, the denarii also used the seated Roma type from the preceding issue, but it is extremely rare and cannot have been struck in any numbers.

Cat. 30, 31, 62–64. Plate II.

Issue 3 had the obverse legend IMP NERO CAESAR AVG PP. The aurei with this obverse legend continued to use the types of Jupiter Custos and Salus unchanged from the previous two issues. The denarii followed the aurei in using these two types, but they also had three further types which were struck solely in silver: a new anepigraphic type of an eagle between two standards and modified forms of both Salus and Roma types, now with their legends across the reverse field and not in the exergue. We can therefore distinguish two stages:

3a. Aurei and denarii with the reverse types of Jupiter Custos and Salus continued without change from Issues 1 and 2.

Cat. 32, 33, 65, 66. Plate II.

3b. Denarii alone in two substantive types of Salus with its legend across the field rather than in the exergue and of the new eagle and standards.

Cat. 67–69. Plate II.

Throughout Nero's reign the issues of gold and silver ran closely parallel to each other; but a number of minor discrepancies between them clearly suggests that the denarii were in fact struck immediately after the similar aurei of each issue. It has been noted that in the dated group the Ceres type, which was abandoned during the issue dated TRP VIIII, is found on the aurei of that year but not on the denarii. Similarly in the undated series both Janus temple and Concordia Augusta types are comparatively common on the gold of the first issue, but on the silver the Janus temple type is not found and the Concordia Augusta is extremely rare. In the later issues with IMP NERO CAESAR AVG PP, the fresh forms of reverse type were introduced during the issue of the denarii, and have left no trace on the aurei.

| 3 |

The relative proportion of the aureus types in TRP VII can be seen in the numbers represented in the large hoard from Pudukota

(NC 1898, pp. 304–20); in other hoards which contain aurei of Nero TRP VII from Pompeii 1812 (Pompeianarum Antiquitatum Historia I.3 [Naples, 1860], pp. 250–51); Utrecht (Opgravingen op het dompe in te Utrecht

1934, pp. 49ff.); Pontalbon (SNR 1900, p. 164); Zirkowitz (Mitteilungen CC Steiermark 2, 173; 3, 157; 5, 109); and Vienna (Jahrbuch für Altertumskunde 1909, pp. 90–95; in the collections of the BM, Oxford, Glasgow, Paris, Milan and Turin; and in the coins from Sale catalogues

represented in the BM collection of photographs.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 |

For a list of these varieties under Nero see the catalogue below.

|

It is important to distinguish from the main series a group of unofficial plated denarii, 5 as the inclusion of some of these in older catalogues has tended to obscure the pattern of the silver issues. These plated forgeries are known in both the dated and the undated series. The obverse and reverse types were almost always those used for the regular denarii. Their dies were often in quite good style and may sometimes have been official dies illegally appropriated from the mint; but the forgers did not hesitate to use obverse and reverse dies in combinations that were quite unknown on the regular coinage. One plated denarius muled an obverse of Nero with the common PONTIF MAXIM reverse type of Tiberius. The obverse legend NERO CAESAR, confined on regular denarii to the reverse type of Augustus Germanicus which completed the legend from the obverse, was used on plated denarii with several other reverse types of the undated series. On regular coins IMP NERO CAESAR AVGVSTVS was only found on Salus denarii with the reverse legend SALVS in the exergue, but on a plated specimen it was muled with a die that had SALVS across the reverse field. Regular denarii dated TRP VI included Nero's fourth consulship in their reverse PONTIF MAX TRP VI COS IIII PP, but plated denarii had PONTIF MAX VI PP alone, omitting all reference to Nero's consulship as the issue TRP II to TRP V had done. 6

| 5 |

For a fuller discussion of Nero's plated denarii see Chapter 2 and its references.

|

| 6 |

The varieties of plated denarii bearing Nero's titulature are listed on p. 243.

|

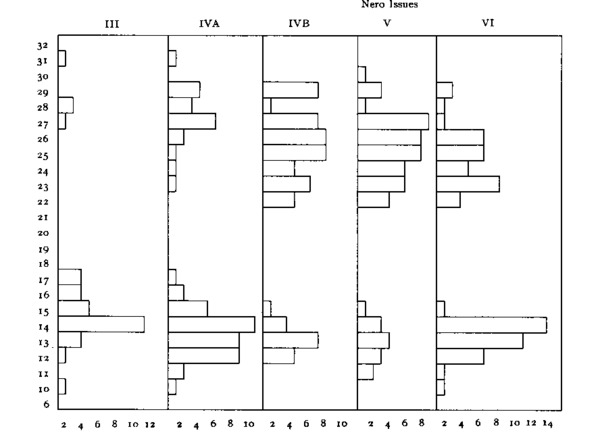

The aes of Nero without SC has long been a puzzle. Recent research has thrown considerable doubt on the older view that down to the time of Gallienus the Roman Imperial coinage was controlled by a dyarchy of Senate and Emperor, and that SC and its absence denoted the product of a Senatorial and Imperial mint respectively. 1 It has become increasingly plain that the distinction was rather one of form than of final intent. 2 Nonetheless SC was given a prominent place on the aes coinage of the Julio-Claudian period and Nero was the first emperor to omit it from any considerable number of his bronze and copper coins, an omission which is the more remarkable in view of the way he introduced a special senatorial reference EXSC on the gold and silver at the beginning of his principate. 3

A careful examination and analysis of the coins which seem to lack SC enables us to define more closely the range and scope of the issues which genuinely omitted it. When worn and tooled examples are excluded, it is clear that the aes is invariably the product of the mint of Rome, and falls into two compact chronological groups. The first consists of copper asses, semisses and quadrantes. The second, slightly later than the first, consists of orichalcum sestertii, dupondii, asses and quadrantes. But each of these denominations, both in copper and orichalcum, is subsequently struck by Nero with the traditional SC on the reverse.

The earliest group consists of asses in copper without SC of the Apollo and Genius reverse types. All the copper asses of these types at the mint of Rome were struck without SC:

Cat. 242

Obv.: NERO CLAVDIVS CAESAR AVG GERM PM TRP IMP PP Head bare r.

Rev.: Nero laureate in flowing robes of Apollo Citharoedus walking r., l. holding lyre, r. playing it. No legend or SC.

| Paris | 11.62 gm. | A301 | P301 |

Plate IX

Cat. 243

Obv.: NERO CLAVD CAESAR AVG GERM PM TRP IMP PP Head bare r.

Rev.: As 242.

| Walters 4 | 11.39 gm. | A302 | P302 |

| Signorelli 1180 | A303 | P302 | |

| Imhoof Blumer 624 | A304 | P303 |

Cat. 244

Obv.: As 221 but head bare l.

Rev.: As 243.

| Oxford | 11.42 gm. | A305 | P304 |

| BM 238 5 | 12.59 gm. | A306 | P304 |

Cat. 245

Obv.: NERO CLAVD CAESAR AVG GERM PM TRP IMP Head bare r.

Rev.: As 242.

| Rome, Terme 6 | 12.00 gm. | A307 | P305 |

| Glasgow 73 7 | 10.46 gm. | A307 | P305 |

| Santamaria, 1924 | A307 | P305 |

Cat. 246

Obv.: NERO CLAVDIVS CAESAR AVG GERMANIC Head bare r.

Rev.: As 242 but with legend PONTIF MAX TRP IMP PP

| Munich | A308 | P306 | |

| Vatican | 10.50 gm. | A309 | P307 |

| Vatican | 10.80 gm. | A310 | P308 |

| Paris | 11.12 gm. | A311 | P308 |

| Oxford | 10.66 gm. | A312 | P309 |

| Mazzini 8 | 10.80 gm. | — | — |

| Newdigate | — | — | |

| Tiber find 9 | — | — | |

| Tiber find | — | — | |

| BM 235 10 | 11.80 gm. | A313 | P310 |

| Walters | 11.53 gm. | A314 | P311 |

| Prince W I, 193 | A315 | P312 | |

| Vierordt 874 | A316 | P313 |

Plate IX

Cat. 247

Obv.: As 246 but head bare l.

Rev.: As 246.

| Paris | 11.67 gm. | A317 | P314 |

| Copenhagen | 13.30 gm. | A317 | P314 |

| Florence | 10.40 gm. | A318 | P315 |

| Oxford | 11.27 gm. | A319 | P316 |

| Mac Dowall 11 | 8.77 gm. | A319 | P317 |

| Weber 1058 | A319 | P318 | |

| Prince W. II, 588 | A320 | P332 |

Cat. 248

Obv.: NERO CLAVDIVS CAESAR AVG GERMAN Head bare r.

Rev.: As 246.

| Oxford | 12.25 gm. | A321 | P319 |

| Tiber find | — | — | |

| Tiber find | — | — |

Cat. 249

Obv.: NERO CLAVDIVS CAESAR AVG GERMA

Head bare r.

Rev.: As 246.

| Munich | A322 | P320 | |

| Mainz | A323 | P321 | |

| Copenhagen | 12.60 gm. | A324 | P320 |

| Sydenham 12 | A325 | P322 | |

| Levis 386 | A325 | P322 |

Cat. 250

Obv.: As 249 but head bare l.

Rev.: As 246.

| BM 236 13 | 11.99 gm. | A326 | P323 |

| Paris | 11.88 gm. | A327 | P324 |

Plate IX

Cat. 251

Obv.: NERO CLAVDIVS CAESAR AVG GERM PM TRP IMP PP Head bare l.

Rev.: GENIO AVGVSTI

Genius standing l. by lighted altar, holding patera and cornucopiae.

| Mazzini 14 | 10.60 gm. |

Cat. 252

Obv.: NERO CLAVD CAESAR AVG GERM PM TRP IMP PP Head bare r.

Rev.: As 251.

| Rome, Terme | 12.02 gm. | A328 | P325 |

| Vienna | 11.00 gm. | A328 | P326 |

| Mainz | A329 | P327 | |

| Glasgow 72 15 | 10.87 gm. | A330 | P328 |

| Oxford | 10.50 gm. | A331 | P329 |

| Rome, Capitol 16 |

Cat. 253

Obv.: NERO CLAVD CAESAR AVG GERM PM TRP IMP P Head bare r.

Rev.: As 251.

| Madrid | A334 | P332 |

Cat. 254

Obv.: NERO CLAVD CAESAR AVG GER PM TRP IMP PP Head bare r.

Rev.: As 246.

| BM 234 | 14.97 gm. | A332 | P330 |

Cat. 255

Obv.: As 254.

Rev.: As 251.

| Rome, Terme 17 | 11.75 gm. | A333 | P331 |

Plate IX

Mattingly and Sydenham described the rare coins with the anepigraphic reverse type of Apollo as dupondii with an As type, 18 but they are undoubtedly copper asses. Specimens which are not patinated have the normal red color of copper, and spectrographic analysis has confirmed this for the British Museum example. (Nero's dupondii at both Rome and Lugdunum were always struck in orichalcum). The weights of the anepigraphic asses range from 11.42 to 12.59 gm., which is well below that of the dupondii without SC but very close to that of the other copper asses without SC.

The Apollo and Genius copper asses without SC are thoroughly Roman in style and undoubtedly circulated in the neighborhood of Rome. One Genius As was found in excavations at Rome; four Apollo asses have been found in the Tiber; and a fifth came from the city of Rome. 19 Information about coin finds in the western provinces is generally far more complete than for Italy, but has not yet yielded a single example. 20