Coinage of the Americas Conference at the American Numismatic Society, New York City

October 29, 1994

© The American Numismatic Society, 1995

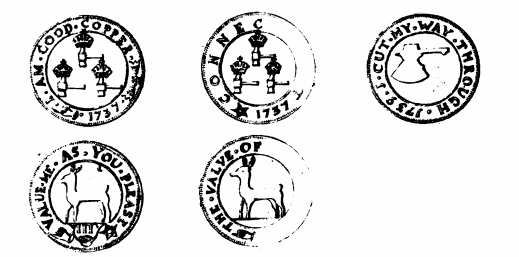

Much of the history of the Higley coppers is still based on legend rather than documented sources. No contemporary reference to their manufacture or use is known. The earliest reference I have been able to locate is a drawing in The Library Company of Philadelphia (fig. 1). This is the work of Pierre Eugène Du Simitière, probably drawn in the 1770s.1 This voracious collector had seven Higley coppers, which he referred to as "deer money." Even then he could not find all varieties in good enough condition to make out the legends.

1. Pierre Eugène Du Simitière Papers , Vol. 3, Item 39b (courtesy, Library Company of Philadelphia).

Numismatists have been trying to fill in the blanks in our knowledge about these intriguing coppers for over two centuries. Even their name can be misleading. They are often known as Granby coppers despite the fact that Granby did not exist until 1786 and the site of the mines has been in East Granby since Granby was divided in 1858. In the 1730s the mine which is the purported source of the Higley coppers was in Simsbury.

We have no reason to doubt the evidence on the coins themselves. They were made in Connecticut between the years of 1737 and 1739. Beyond that, what is known about copper from Connecticut?

It is well documented that copper was discovered in Simsbury, Connecticut in 1705. The Simsbury Town Clerk still has the records of town meetings during this era. At a town meeting in December 1705, it was decided to appoint two men to pursue a report of the discovery of "either silver or copper" in the town.2 In May 1707, the town organized what was the first copper mining company in the colonies. These proprietors tried to lease the mines and receive royalties on copper produced but five years of disputes ensued and it appears that while development of the mines did start, no significant production occurred during the period.

In 1712 a new 30-year lease was signed with Rev. Timothy Woodbridge, Jr. of Simsbury, William Partridge of Newbury, Massachusetts, and Jonathan Belcher of Boston (later Governor of Massachusetts and New Hampshire and then Governor of New Jersey).

Soon after the 1712 lease was signed, development of Copper Hill began. Housing for miners was built as well as a stamping mill for crushing ore. Belcher traveled to England and returned with 12 miners and a refiner. Perhaps to have oversight of the refining, he set up the refinery in Boston and had the ore transported to the Connecticut River and then by ship to Boston. Supposedly because of insufficient volume, he decided to shut this refinery and simply send the ore directly to Bristol, England, for refining after about 1720.

By 1717, Belcher had bought out his father-in-law and Rev. Woodbridge had sold his share to Jaheel Brenton of Rhode Island and two New York City City merchants, Charles Crommeline and Elias Boudinot, an ancestor of the Director of the U.S. Mint by that name.

The other lessees operated somewhat independently of Belcher and organized a refinery in Simsbury. They hired a refiner from Philadelphia, John Hoofman, and also brought over skilled workers from Germany.

While there is no indication that great riches ever came out of any Simsbury mines, large sums were definitely spent to develop them. Belcher complained of losses and mentioned that he invested £15,000 over the 30 years he was involved with these mines (1712-41). This amount corresponds to just over $1 million in current dollars.3 When the 30-year leases expired, mining activity ceased for decades since nobody thought the endeavor would be profitable.

During this period the copper mines in Simsbury were not the only ones in the colonies and probably not the largest. The Schuyler mine in New Jersey (which shipped its ore to Bristol, England) had produced 1,400 tons of ore by 1731.4 This point is important because, while the Simsbury Copper mining experience is a milestone, perhaps the most significant part of this story is not about copper but about steel.

This is where Samuel Higley enters the picture. Higley was born in 1687, the son of a wealthy merchant who had moved to Simsbury in 1684. He was well educated and apparently studied medicine with Samuel Mather and Thomas Hooker.5 In 1714, he received land from his father's estate and he built a house on the property when he married in 1719. In 1728, the General Court granted Higley the exclusive right to make steel in the Colony for a period of 10 years.6 Higley did not have the first copper mine in the colonies. He didn't even have the first copper mine in his town. There is no indication that his steel-making ever became a successful commercial venture, but he may well have been the first skilled enough at the wide variety of tasks required to make steel, make tools from that steel, and use those tools to make coins.

In 1728, Higley bought 143 acres about 1.5 miles south of Copper Hill. We know that copper was mined on that land. We also know that Higley was considered enough of an expert that, in 1732, when there was a dispute about the quality of ore coming from Copper Hill, Belcher called Samuel Higley to Boston to resolve the matter.7 However, Belcher accused Higley of dishonesty, saying he had found the ore to contain 25% copper when he analyzed it in Simsbury but only when 15% copper when he analyzed the same batch of ore for Belcher in Boston. Belcher often complained about his losses from this mining investment, a fact which may have colored this accusation.

It is fortuitous that someone as prominent as Belcher was associated with copper mining in Simsbury because many of his letters

have been saved. Perhaps the only contemporary reference we still have to Higley's mining activity is in a letter from Belcher.

In 1733, he wrote to his attorney, who lived in

Hartford:8

I find after all the mines at Simsbury are not worth the working – It had been well for me those works had ceased

some years ago, but it avails very little to look back – I observe Higley is very slow, and dilatory in the

business – having made out only one ton of ore to this day, and there are but three months more before the winter will be

upon him, so he

may perhaps make out in a whole year 2 or 3 tons of ore – which is a poor story – I am indeed sick of all this affair and

the sooner it is

entirely at an end the better.

Unfortunately, while there are approximately 90 Belcher letters referring to Simsbury copper over the three decades he was involved in the mines, none are known from the period May 1735 to August 1739. Hopefully, some of Belcher's letters from this critical period will eventually be found.

So why do we believe that these copper tokens are indeed the work of Samuel Higley? Basically, we have two lines of evidence. First, family lore. Not to be totally discounted, but neither should these legends be considered totally reliable. Second, his known ability as a steelmaker. While many people in Simsbury were skilled metalworkers, most would have been familiar only with copper or iron work. Striking coins required the ability to work with steel. The evidence points to Samuel Higley. His will was written in 1734 and mentions his mine but nothing about coining equipment. He is believed to have died in 1737, so who struck the 1739 coppers remains a question. A number of sources have claimed that Higley's work was continued by his elder brother, John, Jr., and various other associates. None of these claims has been substantiated. If Samuel Higley died in 1737, the minter of the later issues is still a mystery.

While there is still much historical work remaining to be done on the origins of these coppers,9 we do have dozens of the coins themselves to study. Preliminary results of a metallurgical analysis are presented here, followed by a description of the coins by die varieties and a census of the specimens held in both public and private collections.

Another avenue of research I have undertaken on the Higleys is neutron activation analysis. I have done this work in collaboration with Adon Gordus at the University of Michigan. Basically, we rubbed about 10 micrograms of copper off the edge of a Higley (museums are typically more receptive to this procedure than collectors) and put the rubbing in a nuclear reactor where it was bombarded with neutrons. A small proportion of the atoms of many metallic elements are changed into radioactive isotopes and the energy of the radiation given off is measured which allows determination of the elemental composition of the piece being studied. We looked at genuine Higleys, some suspected fakes, ore I collected from Higley's mine, and contemporary British copper coins. We hoped that the Connecticut ore would have some trace elements which would allow us to distinguish British from American copper. While the analysis was useful for detecting fakes, all the genuine copper coins of the period were roughly similar in elemental composition. But we did debunk the myth that Higleys are rare because they are pure copper and thus were used by goldsmiths for alloying. All the early eighteenth-century copper coins were over 95% copper (mostly 98-99%). The one caveat is that our analysis could not detect tin. For this study therefore, all specimens analyzed were assumed to contain no tin. If Higleys were perceived as purer, it may have been a eighteenth-century myth that led to their selective use by goldsmiths, not an eighteenth-century fact. Further study of the elemental composition of Higley coppers and other contemporary coppers coins should be done using techniques which can detect tin.

In addition to studies of the elemental composition of these Coppers, I believe that other metallurgical studies would be fruitful. There remain many questions about the manufacture of these intriguing tokens. Exactly how were they struck? How many impressions were made from a given die? How were planchets cut and annealed? Were double-struck coins annealed between strikes? Were any dies made after Samuel Higley's death? Who struck these Coppers after his death and why did they eventually stop?

Finally, what was the role of these tokens in local economic life? What was the geographic range of their circulation? How many years did they circulate? The die numbering system I have used continues long held assumptions about the order of striking, based mainly on the legends on these coppers. But were these legends really responses to the acceptance, or lack thereof, of the first Higley coppers on which he tried to annoint upon a half pence worth of copper the value of 3 pence? All in all, the Higley coppers represent a significant chapter in the economic and industrial growing pains of this country. As we learn more about them, we also learn more about economic and technological changes which were simultaneously occuring on the larger scale more commonly considered by historians studying colonial America.

The following abbreviations are used in the descriptive listings: ANS 1914 Exhibition of United States and Colonial Coins (New York City, 1914)

| Chapman | H. Chapman, "The Colonial Coins of America Prior to the Declaration of Independence, July 4th, 1776," The Numismatist 1916, pp. 101-10. |

| Crosby | Sylvester S. Crosby, The Early Coins of America (Boston, 1875). |

| Ellsworth | John E. Ellsworth, Simsbury: Being a Brief Historical Sketch of Ancient and Modern Simsbury (Simsbury, 1935). |

| Kenney | Richard D. Kenney, "Struck Copies of Early American Coins," Coin Collector's Journal 141 (1952), pp. 1-16. |

| Parker | Wyman W. Parker, Connecticut's Colonial and Continental Money, Connecticut Bicentennial Series 18 (Hartford, 1976). |

| Wood | Howland Wood, "A New Variety of the Higley Coppers," The Numismatist 1913, pp. 380-82. |

Crosby knew of 10 varieties from 6 obverse and 5 reverse dies.10 Two new dies and five additional die marriages have been discovered since. All of the genuine dies as well as the Bolen copy are illustrated. In this listing, obverse dies are numbered; reverses are assigned letters. A type known from multiple dies is assigned a second character. This allows the addition of new discoveries which may be made in the future (e.g. a second die of "The Wheele Goes Round" type would be known as 4.2 and the die now known would be changed from 4 to 4.1).

Type 1 Deer surrounded by legend "THE VALVE OF THREE PENCE" Three dies known (1.1 is the obverse of Crosby 17; 1.2 is the obverse of Crosby 18 and 19; 1.3 was unknown to Crosby and apparently discovered by Chapman [fig. 2]).

The right end of the horizontal line beneath the deer is a useful diagnostic, being between "N" and "C" on 1.1, at "C" on 1.2 and hitting "C" on 1.3. The left end of this line is at the edge of the letter "H" on die 1.1 and 1.3 while it points at the center of the letter "H" on die 1.2.

The location of the word "THREE" relative to this line is also useful. On die 1.2 the letters "EE" sit right on the line, while on 1.1 and 1.3, no letters touch the line. The location of the deer's hind legs relative to the dot beneath distinguishes 1.1 (on which the dot is somewhat in front of a point directly below the foot) from 1.2 and 1.3 (on which the dot is directly below the foot). Finally, the spacing of the letters "PEN" differs among the three dies.

The position of the horns is another diagnostic. On die 1.1 the right horn points between "O" and "F", while on 1.2 it points a bit further to the right, i.e. the left edge of "F". While this distinction is small, this horn can be more easily used to distinguish 1.1 and 1.2 from on 1.3, where it is seen to point to the middle of "F".

The Bolen copy made in the mid-nineteenth century is an imitation of die 1.2. There are, however, a number of significant differences. The circle around the deer is complete on the Bolen copy. The copy also has a dot in the C on PENCE. Some worn Bolen copies are known, but even these are readily distinguishable (fig. 3).

Type 2 Deer surrounded by legend "VALVE ME AS YOU PLEASE"

Note the use of V twice in "VALVE". See description of obverse Type 3 for list of differences which can be used to distinguish between Type 2 and Type 3 on specimens on which this letter is either worn or not struck well.

One die known (this die is the obverse of Crosby 20 as well as one marriage unknown to Crosby [fig. 4]).

Type 3 Deer surrounded by legend "VALUE ME AS YOU PLEASE" Three dies known (3.1 is the obverse of Crosby 21 and 23; 3.2 is the obverse of Crosby 22 and 24; 3.3 is the obverse of Crosby 25 and 26; 3.2 and 3.3 are also found in one die marriage each unknown to Crosby [fig. 5]).

If the word "VALVE" is not sharp, Type 3 may be distinguished from Type 2 by other diagnostics. The star is rotated differently and there is a dot between "PLEASE" and the star which follows it. In addition, on Type 2, the spaces between the words "ME AS YOU" are greater than the spaces between these words on all three dies of Type 3. There is also a distinctive die cud in the field of die 2.

Distinguishing between the 3 dies of Type 3 is difficult because so many specimens are well worn. The most useful diagnostic features are the positioning of the letter "L" in PLEASE and the position of the deer's horns. Also useful is the position of "III" relative to the line above. On 3.1 the line is a single broad line while on 3.2 and 3.3 it is a double line. On 3.2 the first and third "I" touch the line above, while none touch on 3.1. (On one impression of 3.2 [in the ANS], "III" does not touch the line above. Therefore this is not a result of die cutting but rather the Roman numerals were so close to the line that this thin piece of metal did not last long and broke off the die.)

Finally, on die 3.3, there are only two arcs below "III", with more on 3.1 and 3.2.

Type 4 Wheel surrounded by legend "THE WHEELE GOES ROUND" One die known (unknown to Crosby; discovered by Wood [fig. 6]).

Given that all features of this die are dramatically different than all other dies no diagnostic details are needed.

Type A Three crowned hammers surrounded by legend "CONNECTICVT 1737"

One die known (A is the reverse of Crosby 17 and 18 [fig. 7]).

The reverse of the Bolen copy is an imitation of die A. The Bolen has an extra bead in the band on the crowns, and since most Bolens are in much better condition than most genuine Higleys this feature is virtually always quite distinct (fig. 8).

Type B Three crowned hammers surrounded by legend "I AM GOOD COPPER 1737"

Two dies known (B.a is the reverse of Crosby 19, 21, and 22; B.b is the reverse of Crosby 20 [fig. 9]).

Even if all the legends were missing, Type A can be distinguished from B by the longer and thinner hammer handles on A and the different relative positions of the hammers.

B.a can be distinguished from B.b using spacing of letters in the legend: "OP" is farther apart on B.a while "PP" is closer on B.a. In addition, "1737" is spaced wider on B.a and the dot before the hand is lower on B.a (i.e. closer to the center of the coin). The dot after "COPPER" is lower and further away on B.a (relative to the letter "R"). Finally, the ornament between "COPPER" and "1737" is smaller on B.a and also somewhat different in design.

Type C Broadaxe surrounded by legend "J CUT MY WAY THROUGH" One die known (C is the reverse of Crosby 23, 24, and 25 [fig. 10])

Most specimens show a die break at the letter "T". One specimen known without this die break is of variety 3.1-C, therefore yielding information about emission sequence; 3.2-C and 3.3-C are later uses of this reverse die since all impressions show the die break.

Type D Broadaxe surrounded by legend "J CUT MY WAY THROUGH 1739" One die known (D is the reverse of Crosby 26 [fig. 11]).

Even if the date is worn or not struck up, Type D can be distinguished from Type C by the position of the legend relative to the broadaxe. The handle points to the letter "Y" on Type C and to the letter" T" on Type D.

Attributing Higley coppers can be time consuming on worn specimen. In addition, a number of specimens are known which have been double struck. Given the uneven planchets, I believe that many of these double strikes are not errors but attempts to improve coins which did not receive an adequate initial impression. When using relative position of design elements, one should be aware of whether or not the coin at hand is double struck as this will, of course, affect alignment of elements from the two strikes. The fact that the second strike often leaves much of the first impression visible indicates that the faces of the two dies were often not quite parallel. This suggests that these coppers were hammer struck, though further study is neccesary to determine whether the dies were hinged together to provide some degree of alignment or whether the dies were completely unattached.

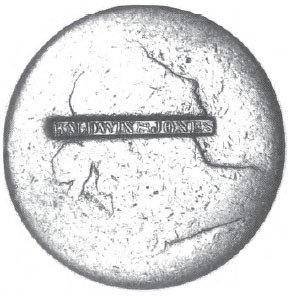

There is one specimen which presents another mystery. The ANS owns a copper which looks unlike any other Higley (fig. 12). This may be a counterfeit or a reengraved piece but differs so dramaticaly in quality of engraving that it is difficult to imagine that it is from the same hand as any of the other Higley coppers. Further study of this specimen is warranted to determine the method and date of its manufacture as well as the identity of its maker.

From these 8 obverse and 5 reverse dies, 15 die marriages are known to date, of which Crosby knew of 11. Listed below are the die marriages known to Crosby, keyed to the illustration numbers on his plate 8, and those marriages discovered by others since. A listing of a census of individual specimens is found in Appendix 1.

| 1.1-A | Crosby 17 |

| 1.2-A | Crosby 18 |

| 1.3-A | Discovered by Chapman before 1916 |

| 1.2-B.a | Crosby 19 |

| 2-B.a | Discovered by Freidus in 1985 |

| 2-B.b | Crosby 20 |

| 3.1-Ba | Crosby 21 |

| 3.2-B.a | Crosby 22 |

| 3.3-B.a | Discovered by Dr. Hall (marginal note in his copy of Crosby in the ANS, indicating that he knew of 3.3-B.a and apparently owned a specimen) |

| 3.1-C | Crosby 23 |

| 3.2-C | Crosby 24 |

| 3.3-C | Crosby 25 |

| 3.2-D | Discovered by Freidus in 1985 |

| 3.3-D | Crosby 26 |

| 4-C | Discovered by Wood |

The following census information should be considered a snapshot of a process rather than a definitive finished product. There are Higleys which I have been told of but which I cannot verify because I have seen neither the coin nor its photograph. Surely there are also those which have not even come to my attention. Readers who know of specimens not included in this census are asked to contact the author through the ANS.

A name followed by a number indicates a specimen's owner and lot number if sold at auction or accession number if owned by an institution. If sold at auction, the cataloger and date of the sale follow in parentheses. An asterisk following an entry indicates the steward of a specimen at the time of this writing. Entries followed by a dash indicate that the current location is not known to the author.

| 1.1-A | 1) Crosby:948 (Haseltine 6/27/1883); Newman* (Crosby 17 [plate coin]) |

| 2)Jenks:5431 (H. Chapman, 12/7/21); Stack's 10/20/87, 23 – (10.37 g) | |

| 1.2-A | 1) Connecticut Historical Society* (Parker, p. 24) |

| 2) Bushnell: 189 (S.H. and H. Chapman 6/20/1882); Zabriskie:34 (H. Chapman 6/3/09); SI* | |

| 3) Fleischer:477 (Stack's 9/7/79) – (9.66 g) | |

| 4) Parmeee:274 (New York City Coin and Stamp 6/25/1890) — | |

| 5) Mayflower 3/29/57, 1626 — | |

| 1.3-A | 1) Connecticut State Library:8675* (8.25 g, 2 holes) |

| 2) Picker:98 (Stack's 10/24/84; anonymous collector | |

| 3) Roper:l48 (Stack's 12/8/83; Groves* (7.76 g) | |

| 4) Woodward 3/13/1865, 2594; Heman Ely: 1054 (Woodward 1/8/1884); Massamore; Garrett:1303 (Stack's 10/1/80); Roper: 149 (Stack's l2/8/83)—(9.80 g, plugged) | |

| 5) Newman* | |

| 6) H.M. Sturges (1954); Simsbury Historical Society* | |

| 1.2-B.a | 1) Bushnell:190 (S.H. and H. Chapman 6/20/1882); Parmelee – (kenney, p. 9) |

| 2) Norweb:1238 (Bowers and Merena 10/12/87); Linett (10.05 g) | |

| 2-B.a | 1) Krugjohann:23 (Bowers and Ruddy 5/14/76); Roper: 150 (Stack's 12/8/83); N.Y. dealer; anonymous collector – (10.05 g) |

| 2) Newman* (10.09 g) | |

| 2-B.b | 1) Parmelee:276 (New York City Coin and Stamp 6/25/1890); Mitchelson; Connecticut State Library:8666* (7.10 g) |

| 3.1-B.a | 1) Hall:28 (Stack's 5/15/45); H.M. Sturges (1954); Simsbury Historical Society* |

| 2) Zabriskie:35 (H. Chapman 56/3/09); Connecticut Historical Society* | |

| 3) Bascom:41 (H. Chapman 1/16/15); Ellsworth (3/23); Garrett:1304 (Bowers and Ruddy 10/1/80) – (9.34 g) | |

| 4) Colvin:106l (Numismatic Gallery 8/25/42); Robison:60 (Stack's 2/10/82); Stack's FPL 1989, C65 (8.01 g) | |

| 5) Mickley:2405 (Woodward 10/28/1867); Stevens; Bushnell:191 (S.H. and H. Chapman 6/20/1882); SI* (8.66 g) | |

| 6) Newman* (9.23 g) | |

| 7) Jackman:72 (H. Chapman 6/28/18) — | |

| 8)Mayflower 10/12/57, 4 — | |

| 3.2-B.a | 1) Crosby:949 (Haseltine 6/27/1883); Parmelee; DeWitt Smith (12/08); Brand:953 (Bowers and Merena 6/18/84) – (Crosby 22 [plate coin]) |

| 2) Roper: 151 (Stack's 12/8/83); N.Y. dealer – (8.62 g) | |

| 3) ANS* (8.18 g) | |

| 4) New Netherlands 7/21/76, 812; Groves* | |

| 5) Norweb: 1239 (Bowers and Merena 10/12/87) — | |

| 3.3-B.a | 1) Jackman:71 (H. Chapman 6/28/18) — |

| 2) Stack's 12/7/79, 23; Cowden:913 (Stack's 12/1/93) – (9.75 g) | |

| 3.1-C | 1) Sarah Sofia Banks (1818) - BM* (8.53 g) |

| 2) Picker (1969); Park: 136 (Suck's 5/26/76) — | |

| 3) Lauder:163 (Doyle 12/15/83; [Arnold-Romisa]:579 (Bowers and Merena 9/17/84); Stack's FPL 1992, 220 – (9.64 g) | |

| 4) ANA auction (Kagin's 8/16/83; Early American Numismatics; anonymous collector* | |

| 5) Connecticut State Library:8665 (9.54 g) | |

| 3.2-C | 1) Miller: 1799B (Elder 5/26/20); Garrett: 1305 (Bowers and Ruddy 10/1/80); Picker – (10.51 g) |

| 2) Bushnell: 192 (S.H. and H. Chapman 6/20/1882); SI* (8.35 g) | |

| 3) Gschwend:45 (Elder 6/15/08); S.H. Chapman; Robison:6l (Stack's 2/10/82; Stack's FPL Fall 1983, 594; Superior 1/30/84, 20; Stack's FPL June 1986 – (ANS 1914. Numerous electrotypes of this specimen exist) | |

| 4) C. Hawley; Anton; Roper: 152 (Stack's 12/8/83; Anton; anonymous collector – (9.84 g) | |

| 5) Merkin 9/11/74, 250; Bowers and Ruddy, Rare Coin Review 22, 23, 24, 25 (1975, 1976); Kriesberg 10/24/78, 25; Early American Numismatics ("Buy or Bid" 7/85) – (9.64 g) | |

| 6) Sarah Sofia Banks (1818); BM* (9.72 g) | |

| 7) Newman* | |

| 8) Jackman:73 (H. Chapman 6/28/18) — | |

| 3.3-C | 1) Zabriskie:39 (H. Chapman 6/3/09); Picker:99 (Stack's 10/24/84) – (7.13 g) |

| 2) Zabriskie:40 (H. Chapman 6/3/09); Norweb (1982); SI* (10.17 g) | |

| 3) DeWitt Smith (12/08; Brand:954 (Bowers and Merena 6/18/84); anonymous collector* | |

| 4) Stickney:97 (H. Chapman 6/25/07) – (10.11 g) | |

| 3.2-D | 1) Bushnell: 193 (S.H. and H. Chapman 6/20/1882); Ellsworth; Garret:1307 (Bowers and Ruddy 10/1/80; [Sonderman]:19 (Stack's 5/2/85); Freidus* (7.74 g) |

| 2) Connecticut State Library:8668* (9.42 g) | |

| 3) Zabriskie:4l (H. Chapman 6/3/09); Newcomer; Newman* (9.69 g) | |

| 4) Norweb:1240 (Bowers and Merena 10/12/87) – (8.28 g) | |

| 5) Col. Green; Mayflower 3/29/57, 1628; Oeschner:9277 (Stack's 9/8/88) – (9.10 g) | |

| 3.3-D | 1) Massachuettss Historical Society:84 (Stack's 3/29/73; Steinberg: 51 10/17/89); Early American Numismaticss FPL 12/93; Long Island collector* (11.11 g; plugged; reverse used for Crosby 26—plate is of electrotype, so hole not evident.) |

| 2) Connecticut Historical Society* | |

| 3) Zabriskie:42 (H. Chapman 6/3/09) – (6.16 g) | |

| 4) Zabriskie; ANS* (8.40 g) | |

| 5) Brand; [Breisland:8311 (Stack's 6/20/73); Roper: 153 (Stack's 12/8/83); Groves* (8.55 g) | |

| 6) Morris; Jenks:5432 (H. Chapman 12/7/21) – (8.00 g) | |

| 7) NASCA 11/77, 58; Early American Numismatics ("Buy or Bid") Summer 1985, 125 (10.72 g) | |

| 4-C | 1) Wood; Garrett: 1306 (Bowers and Ruddy 10/1/80); Roper: 154 (Stack's 12/8/83); Groves* |

| 1 |

Joel J. Orosz, The Eagle That is Forgotten. Pierre Eugène Du

Simitière, Founding Father of American Numismatics (Wolfeboro, NH,

1988), p. 25, fig. 2.

Thanks are due to the many people who have given freely of time and information, including Eric P. Newman, Anthony Terranova, Joel Orosz, Alan Weinberg, Donald Groves, and many librarians, curators, and directors of museums and historical societies as well as other anonymous collectors and dealers. Some remain anonymous according to their wishes, others are temporarily relegated to that status by my faulty memory. |

| 2 |

Creel Richardson, A History of the Simsbury Copper Mines, Ms.

(Trinity College, Hartford, 1928), p. 1 (citing unpublished

Simsbury Town Records).

|

| 3 |

John J. McCusker, How Much is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a

Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States

(Worcester, MA, 1992), pp. 323-32 (Table A-2).

|

| 4 |

James A. Mulholland, A History of Metals in Colonal America (University, AL, 1981), p. 46.

|

| 5 |

Mary J. Springman and Betty F. Guinan, East Granby: The Evolution of a Connecticut Town (Canaan, NH, 1983), p. 23.

|

| 6 |

Lucius I. Barber, A Record and Documentary History of Simsbury

(Simsbuy, CT, 1931), p. 384 (citing unpublished

Connecticut Colonial Records, vol. 7, p. 174).

|

| 7 |

Richardson (above, n. 2), p. 51.

|

| 8 |

Richardson (above, n. 2), p. 57 (citing an unpublished letter in the collection of The Massachusetts Historical Society.

|

| 9 |

In addition to works cited above, the following have been consulted in the preparation of this study:

Albert C. Bates, Sundry Vital Records of and Pertaining to the Present Town of East Granby, Connecticut 1737-1886 (Hartford, 1947); Mary C. Johnson, The Higleys and Their Ancestry (New York City, 1896); Alice H. Jones, Wealth of a Nation To Be (New York City, 1980); John D. Perin, Geology of the Newgate Prison Mine of East Granby , Ms. (University of Connecticut, Storrs, 1976); Edwin J. Perkins, The Economy of Colonial America, 2nd ed. (New York City, 1988); Noah A. Phelps, History of Simsbury, Granby and Canton, from 1642 to 1845 (Hartford, 1845); Lawrence Scanlon, "A New Look at an Old Map," The Lure of the Litchfield Hills 45 (1974, pp. 28-37; Mary K. Talcot, Collections of The Connecticut Historical Society, Vol. 5, The Talcott Papers. Correspondence and Documents (Chiefly Official) During Joseph Talcott's Governorship of the Colony of Connecticut, 1724-174. Part 2, 1737-41 (Hartford, 1896). |

| 10 |

Coinage of the Americas Conference at the American Numismatic Society New York City

October 29, 1994

© The American Numismatic Society, 1995

Coins and tokens provide the evidence not only for portraits, but also for vanished edifices.1 The most spectacular example of this is the Colosseum sestertius issued under the Emperor Titus, which shows us the Colosseum as a perfect circle, with the crowds inside, and on the outside, the baths of Titus and a column, the Meta Sudans (fig. 1), which survived until the 1930s but was then destroyed by Benito Mussolini. Ironically, although we have a good idea of how the 2,000 year-old Colosseum looked, we have many problems when we try to figure out how the New York City Theatre looked, which is less than 200 years old. I have been assured by a Roman numismaist,2 however, that it is far easier to reconstruct these buildings when there are substantial remains, as in the case of the Colosseum.

In the case of the Theatre at New York City token, not only is there disagreement as to the appearance of the actual building, but there is disagreement as to which building is represented. John and Damia Francis concluded the token showed the First Park Theatre, and Walter Breen adopted their conclusions in his Encyclopedia 3 Francis W. Doughty,4 however, argued at a meeting of the American Numismatic Society on February 17, 1886, that the building depicted on the token is not the First Park Theatre, but rather the John Street Theatre.5 Recently Michael J. Hodder has revived this argument, who, when he reviewed the ANS benefit auction by Stack's in the C4 Newsletter, said, "The Theatre at New York City token is correctly described as showing the John Street Theatre, not the Park Theatre as had been believed before (and as is in the Red Book and Breen)."6 This revision has been incorporated into the 1995 edition of the Guide Book of United States Coins (the Red Book).7

The Theatre at New York City token has had an unfortunate cataloguing history.

Cataloguers of the British token coinage of the eighteenth century have rejected it as American; cataloguers of early American

coins have rejected it as British. James Conder, one of the earliest cataloguers of the tokens of the late

eighteenth century, commented about American pieces, I have in my possession fifty-five different American pieces, some minted there, and

others in Great Britain; several of which, circulated in this country, were improperly included in the lists that

have been published, as the Medalet of "Washington," "United States," "New York City Tokens;" but such are

wholly omitted in this arrangement. They may be collected as American Pieces, but can never be regarded as British.8

James Atkins in 1892 followed Conder's arrangement and did not include these tokens.9 Richard Dalton and Samuel H. Hamer, fortunately, did include the Theatre at New York City token in their catalogue of 1910 (Dalton-Hamer.Middx.l67), as did R. C. Bell in 1978 (Bell.S.40), although Bell calls it a "problem piece."10

In the American literature, Crosby did not include this token, although he did include the Franklin Press token—which is another Conder token. Although shunned by the reference books, the token appeared occasionally at important U.S. auctions. The earliest appearance I have found was the McCoy auction by Woodward (1864), where the token realized $21, being sold to Levick. 11 This same specimen was sold in Woodward's auction of Levick's collection of 1884, which had a photographic plate as frontispiece.12 This is the earliest illustration I have found; however, it depicted only the obverse of the token (as did the plate in the John Story Jenks sale auctioned by Henry Chapman in December 1921).13 The token was accepted into the American series as the result of the work of Dr. Benjamin P. Wright and Edgar H. Adams. In The Numismatist for October 1899, Wright listed the token we know and the muling in tin of the Theatre at New York City token and the "Antient Scottish Washing" reverse. Wright gave them variety numbers Wright. 1130 and Wright 1130A. Wright also published a crude but fairly accurate line drawing of the token and the muling; although the obverse appeared in the photographic plate of the Levick sale, this is the earliest illustration of the reverse and the muling.14 Adams was charged by the New York City Numismatic Club with editing a list of New York City storecards. This work began by reprinting in 1913 the listing of New York City State storecards which had been published in the Coin Collector's Journal for 1884-86.15 Neither of these catalogues included the New York City Theatre token. In 1920, however, Edgar H. Adams published a comprehensive catalogue of tokens from all the states, and this did include the New York City Theatre token. Adams probably picked it up from an auction catalogue, such as the auction of the Levick collection, or from Wright's listing.16 Adams listed two varieties: one with a lettered edge (Adams.892; listed in Breen as Breen.1055) and one with a plain edge (Adams.893; Breen. 1056). From there it was introduced into Wayte Raymond's standard coin and token catalogues.17 After Raymond's death his catalogue continued to be published for a few years, although Yeoman's "Red Book" gradually replaced it in the marketplace. The token, however, did not get into the Red Book until the 1972 edition, which appeared in July 1971, and even then it did not rate a photograph—nor has it ever obtained one since.18 Of course, it is much larger than most of the coins listed in the Red Book, so perhaps it took up more space than the book could spare.

The obverse of the token depicts a building with a hexastyle portico (fig. 2), plus further columns on the sides, with the inscription "The Theatre at New York City/America," signed, "Jacobs." Our work is made much easier because of the work of the architect and architectural historian Isaac N. P. Stokes, a trustee and major donor to the New York City Public Library, who was fascinated with early pictures of New York City City and of New York City City buildings. (Stokes was also the architect of the American Geographical Society building on Audubon Terrace.) Stokes is a pioneer of the preservation movement which Ada Louise Huxtable revived with her superb Classic New York City in 1964.19 It was Stokes who hired Berenice Abbott to photograph New York City City buildings threatened with destruction.20 Stokes collected and published six massive volumes identifying views of New York City City and various New York City edifices, and this provides us with a ready-made index of views of New York City City.21 The crucial view is in Longworth's New York City City directory of 1797, which contains a gatefold depicting the New Theatre (fig. 3).22

The inscription of the engraving says, "The New Theatre." We know the date of this engraving, because it was bound in with the city directory of 1797, and it is specifically referred to on the title page of the directory. It is not an accidental binding of two extraneous things. This engraving was intended for the 1797 directory. This theater was new in 1797. The John Street Theatre, which Doughty and Hodder proposed for the token, was built in 1767, and could not be called "the New Theatre" in 1797; in fact, it was referred to at the time as "the Old Theatre."23 The Park Theatre, which was first called the New Theatre, to distinguish it from the John Street Theatre, had its cornerstone laid on May 5, 1795.24 After many delays in construction, it finally opened on January 29, 1798.

New York City City directories in this early period were made to be ready by the fourth of July. They were dated by "the year of American independence." One reason was that May first was "moving day," when many New Yorkers changed their domiciles; and so directories were prepared after that date. We know that the custom of "moving day" already existed in the eighteenth century, because in William Dunlap's play of 1789 (The Father of an Only Child) we find the phrase, "His head is like New-York on May day, all the furniture wandering."25 The preface to David Longworth's New York City City directory of 1796 is signed June 11, 1796.26 In the text of Longworth's 1797 directory, there is a reference to an agreement between the United States and the Spanish consul in Philadelphia on May 17, 179727 so the directory must have been typeset after that; but it would have to be ready in time for July fourth. The engraving therefore shows the theater as it appeared in or before the spring of 1797. The theater was then still under construction; and a careful examination of the engraving reveals that the theater does not yet have a roof: the sunlight is hitting the interior rear wall. We do know when the roof was put on the Park Theatre; the New York City merchant Walter Rutherfurd wrote to his son, John Rutherfurd on October 2, 1796, saying, "Our great buildings make good progress....The Play House is roofed and the States Prison has three hundred men at work on it,"28 which suggests that Tisdale's drawing antedates October 1796. The engraving therefore shows the theater under construction, as it was in the autumn of 1796; this is the New Theatre, which later was called the Park Theatre.

In short, the First Park Theatre attribution, proposed by John and Damia Francis and by Walter Breen, is correct, and the John Street Theatre attribution, proposed by Doughty and revived by Hodder, is wrong.

There are some small differences between the token and the engraving, but Jacob has been fairly faithful, particularly in his depiction of the eagle. Jacob has changed the Corinthian pilasters to Doric ones, and he has omitted the ironwork on the balcony, but generally he has made an almost slavish copy.

The frontispiece depicting the theater in Longworth's 1797 New York City City directory exists in at least two versions. The New York City Public Library copy of the directory has the earlier version, which is signed "Tisdale delin[avit] et sc[ulpsit]." This particular version was already catalogued by Stauffer (Stauffer.3258).29 The American Antiquarian Society copy of the directory has what is probably the second version, which is signed "J. Allen sc[ulpsit] Tisdale del[inavit]," which means that the picture is by Tisdale, but the engraving work was done by Allen.30 Presumably Tisdale first did both the drawing and the engraving, but the engraving was found to be unsatisfactory, whereupon Allen was called in to redo it.

Tisdale is Elkanah Tisdale, a painter and engraver, who spent most of his life in Connecticut but was living in New York City City at this point. Stauffer says that he was born in Lebanon, Connecticut, about 1771, and was still alive in 1834, although this is contradicted by my reading of the census, which leads me to believe that he was born in 1761 and was dead by 1810.31 Tisdale came from a family in Lebanon, Connecticut, who traditionally gave their menfolk names from the Old Testament beginning with the letter "E." The 1790 census lists three Tisdale households in Lebanon, Windham County, Connecticut: Elijah Tisdale, whose household had seven free white males of sixteen and over, including himself, four free white males under sixteen, and seven free white females; Ebenezer Tisdale, who was living with three free white females; and Eliphalet Tisdale, who was living with two free white females. Presumably Elkanah was the son of Elijah, one of the free white males above the age of sixteen in his household. These peculiar names beginning with "E" were thus a family custom, although Old Testament names were common in Lebanon. There were at least two other Eliphalets in Lebanon in 1790; other remarkable Puritan Old Testament names included Amaziah Chappel and Flavel Clark. There was one lady with a more traditional Puritan name: Experience Brewster. Of the 574 families in Lebanon, nineteen owned slaves, most only one or two or three; the one exception was Elijah Mason, senior, who owned 28 slaves, or more than 1% of all the slaves in Connecticut. The 1800 census for Lebanon, Connecticut, showed Ebenezer Tisdale, then aged 45 or more, living with a free white female aged 26-44 and another free white female aged 45 or more; presumably the former was an unmarried daughter, the latter a wife. Elkanah Tisdale headed another household in Lebanon: his household had two free white males aged 10 to 15, one free white male aged 16 to 25, and one free white male, presumable Elkanah himself, aged 45 or over; the free white females included three aged 16 to 25, presumably the daughters, and one aged 45 plus, presumably Tisdale's wife.33 Elkanah Tisdale appears to have been dead by 1810: the 1810 census shows only one Tisdale household in Lebanon, which was headed by Widow Tisdale, aged 45 or more, with two free white males aged 26 to 44, two free white females aged 10 to 15, and one free white female aged 26 to 44, presumably all sons and daughters.34

Lebanon, Connecticut, was a good place to be from; some of the Trumbull family came from there. It does not seem to have been an entertaining place to live, however. When the Duc de Lauzun and his French troops were quartered there during the American War of Independence in 1780, Lauzun commented, "Only Siberia can be compared to Lebanon, which is merely made up of some cabins dispersed among immense forests."35 In the colonial period it was on the direct route between New York City and Boston. The change in that route, and the opening of the Erie Canal, which exposed Connecticut farms to the competition of the Middle West, led to a dramatic fall in the town's population during the nineteenth century.36

Elkanah Tisdale is listed for the first time in William Duncan's New York City City Directory for 1794, which was printed in June 1794. He is then living at 15 New Street, and his occupation is "engraver." He remained there until David Longworth's directory printed in June 1798, whereupon he is listed at 8 John Street and his occupation is given as "miniature painter."37 He is not listed in the 1799 directory or in any other subsequent directories, and biographical sources on Tisdale say that he then moved to Hartford, Connecticut, where he founded the Hartford Graphic & Bank Note Engraving Company.38 Tisdale did another frontispiece for Longworth's directory: the 1796 New York City City Directory has a frontispiece signed "Tisdale," depicting the Tontine City Tavern, with the title below it, "A View of the New CITY TAVERN." Early New York City directories liked to add views and maps of the city as an additional selling point, as yellow page telephone directories do even today.

Tisdale was a good miniaturist, but a poor engraver, which may be why the engraving was given to someone else, namely Joel Allen, who was also from Connecticut. About Joel Allen we know very little. Stauffer says he was born in 1755 at Southington, Connecticut, and died in 1825; he later settled in Middletown, Connecticut. Allen served in the American War of Independence. The only trace I have found of him in the census is in the second census of 1800, which shows him living in Southington,Hartford County, Connecticut. Joel Allen is aged 26 to 45, and heads a household including a free white male aged under 10, another free white male aged 16 to 25, a free white female aged under 10, and a free white female, presumably his wife, aged 26 to 45.39

Allen and Tisdale were both employed in making the engravings for the American edition of George Henry Maynard's translation of the works of Flavius Josephus. This American edition, like many early American editions, used the same sheets as the British edition, but changed the title page (at least twice: for New York City and for Baltimore) and added sixty engraving.40 It is possible that that is how Tisdale and Allen came into contact, but the directory and the edition of Josephus were made for different publishers (Thomas Swords published the directories, William Durrell published Josephus).

There is a drawing which deceived the New York City City theater historian, Professor George C.D. Odell, amongst others, into believing that it was an original. This is a sketch, or very possibly a tracing, of the Tisdale/Allen engraving, which Odell came across in the collection of the New-York Historical Society. It is clearly copied from the Tisdale/Allen engraving, because it uses cross-hatching to represent shadows, which are only needed on an engraving, and are unnecessary for a pencil drawing. It is also slightly cruder than the Tisdale and the Tisdale/Allen engravings.41

Did the engraving faithfully depict the theater? The answer is yes and no. A painting of 1798 by Milbourne shows us what is now Park Row, with the New Theatre, and we can see that the eagle frieze was not used, and that the ironwork on the balcony is slightly more elaborate (fig. 4). I think the engraving had added to it some elements to make the theater appear as if it were finished: the frieze was added, the balcony added, and probably the glass in the windows. But aside from these falsifications, the engraving is a faithful depiction made from a picture done in situ: a comparison of the topography with the engraving shows it to be accurate. On the right of the Tisdale engraving we see the steeple of the North Dutch church, very low down, which is correct, because the streets to the east of Park Row drop steeply toward the East River.

Richard Beamish, the biographer of the theater's architect, Brunel, says of the theater, "The cupola by which it was surmounted is said to have resembled that in Paris over the Corn Market, while in boldness of its projection and in the lightness of its construction it was far superior."42 It is true the theater had a dome, but it was an interior dome, not visible from outside. Beamish's accounts of Brunel's life in the United States are not always reliable, possibly based on inaccurate family anecdotes.

The reverse of the New York City Theatre token depicts two ships at anchor, a bail, an anchor, and a cornucopia, with a blank exergue where we would expect a date (fig. 5). The one type which occurs elsewhere in Jacob's work is the cornucopia; there is a close parallel in the reverse of his penny depicting the House of Commons of 1797 (Dalton-Hamer.Middx.173; fig. 6). On both obverse and reverse the lettering is done by hand, not with punches. This is characteristic of the work of Benjamin Jacob, and is unusual for this period, when most diesinkers used punches. The reverse is found combined with no other token of the period. This is unusual for British tokens of the late eighteenth century (the Conder series), where muling is very widespread. This led Arthur W. Waters, writing in 1954, to suggest that the New York City Theatre token was actually made up for some commercial purpose, rather than just for collectors.43 I shall discuss this question further below.

The edge of the ANS specimen reads, "I PROMISE TO PAY ON DEMAND THE BEARER ONE PENNYx". A different specimen with this same edge reading was auctioned as part of the Colonel Walter Cutting Collection by Lyman H. Low in May 1898.44 The 51st sale of New Netherlands, lot 180, reports that reading.45 Bowers and Ruddy catalogued the Garrett specimen with that readng.46 Stack's reported the Roper specimen as also having that reading.47 Breen, however, gives the edge as "WE PROMISE TO PAY ON DEMAND THE BEARER ONE PENNYx" "as on other Jacobs tokens" and says that "the rumor of two minor varieties remains unconfirmed."48 All the Jacob penny tokens I have examined, however, read "I PROMISE," as in the ANS, Cutting, New Netherlands, Garrett and Roper specimens, not "WE PROMISE." A third potential variety is that catalogued by William E.Woodward as lot 2463 of the Levick sale: "I promise to pay the bearer one penny."49 A fourth possible variety of edge lettering was listed by Henry Chapman in lot 5508 of the Jenks Collection, where he sold a Theatre at New York City token with the edge variety reading, "WE PROMISE TO PAY THE BEARER ONE PENNY."50 Until confirming evidence emerges, it appears that the correct edge reading is "I PROMISE TO PAY ON DEMAND THE BEARER ONE PENNYx" and that Breen, Woodward, and Chapman erred in transcribing the edges.

Many Jacob tokens do show slippage of the edge dies, so that the T of THE is right next to or over the D of DEMAND. This slippage is perfectly possible with New York City Theatre tokens, so cataloguers should keep an eye out for edge errors.

Another possible edge variety is a Theatre at New York City token with a plain

edge. The oldest listing I have found of this is the listing by Edgar H.Adams in 1920 (Adams.NY.893).51

Breen, however, could not confirm the existence of this token, and calls it "unverified." If discovered, one would

have to ascertain that it was a true plain edge, and not filed down. Samuel H. Hamer comments about this pernicious

practice:

Charles Pye refers to the Collector who, when he finds it difficult to procure a scarce variety of a coin, by

means of filing and chasing a common impression of the same coin, contrives to patch up an imitation of a rare variety. Unfortunately,

the

evil which such men do lives after them, and as a result, an unpublished "Plain edge, in collar," may appear. A careful examination

may

show traces of filing, in which instance the specimen should be regarded as an ordinary one, the edge of which has been tampered

with; or,

an apparently genuine "Plain Edge in Collar" may have been produced by "turning" the edge in a lathe; but as such treatment

would render the specimen smaller in diameter than the ordinary ones, a comparison will reveal the true character of the piece.52

A further source of varieties is the die axis. Jacob's tokens show much variation in the die axes. The die axis of the ANS specimen of the New York City Theatre token is just slightly off six o'clock, which is presumably the same as that reported for the Norweb specimen, "195 degrees"; any other die axis would be worthy of remark.

Donald Scarinci has estimated that there are at least 14 tokens still extant.53 None of the tokens appears to have experienced any circulation. All are proofs.

Breen warns against the existence of casts and electrotypes, although I have never seen a fake Theatre at New York City token of any kind.54

There is one mule of this token. This combines the New York City Theatre obverse

with "Antient Scottish Washing." This was listed by Wright as part of his collection, writing, I have another

with the following reverse: A woman treading clothes in a tub between sprigs of thistles. Inscription, "Antient Scottish

Washing—*Honi.Soit.Qui.- Mal.Y.Pense.*" The metal resembles Tin. This appears as the reverse of the Loch Leven penny. The

edge is plain and

is a remarkable specimen of a unique muling. It has never been published before.55

This specimen passed from Wright to Frederick C.C. Boyd, and was listed by Breen as being in the collection of John J. Ford, Jr. Mules are quite common in the Conder token series—Conder himself disapproved of them as a gimmick —and Peter Skidmore issued many mules, because he came into the dies of Thomas Spence, and then issued tokens muled with his dies, often cut by Jacob, and those of Spence, which are usually more artful. (On Peter Skidmore acquiring Spence's dies, see The Gentleman's Magazine, June 1797.)56 Presumably the mule was created by Peter Skidmore.

The architect of the Park Theatre was Marc I. Brunel, knighted in 1841, famous for his construction of the Thames Tunnel, which opened in 1843 (fig. 7). Fleeing the French Revolution, Brunel arrived in New York City City on September 6, 1793.57 When Pierre Pharoux and Simon Desjardins went upstate to survey land for the Castorland project, a settlementt project for Frenchmen emigrating to the United States, they encountered Brunel in Albany, who proved to be of much assistance.

Numismatists are well acquainted with the Castorland project, because of the very attractive tokens made up to compensate directors for attending board meetings (fig. 8); the silver specimens later circulated, being accepted as the equivalent of a half dollar.58 Backed by a New York City merchant, Thurman, the three French emigrés supervised the construction of a canal from Lake Champlain to the Hudson River.59 Brunel's biographers say that Brunel won the contest to design the United States Capitol, but his design was not carried out because of expense. There is no record of Brunel's design among the contest entries, nor is there any record of his winning the first competition, but the records of that first competition are fragmenary.60 It is possible that Brunel did enter the contest, but it seems unlikely that he could have won it and no record of his name be left among the surviving documents. On August 2, 1796, Brunel swore an oath before the United States District Court of the District of New York City to become a United States citizen.61 Brunel served as chief engineer of the City of New York City and drew up plans for a cannon foundy.62 Brunel won an architectural contest to design the new theater; he had his friend Pharoux, whose plan lost out, do much of the interior decoration.63 When the Theatre was opened, one newspaper named as the architect not Brunel or Pharoux, but the Mangin brothers, of whom Joseph-François would later be one of the architecs of City Hall and old St. Patrick's Church (formerly the Roman Catholic Cathedral) at Mott and Prince streets. Joseph-François and Charles Mangin were also architects of the State Prison erected in Greenwich Village in 1796-97, located north of Christopher Street, between Washington Street and the Hudson River. By 1803 Joseph-François Mangin was also serving as City Surveyor, and drew a map of the city that year.64 All these French emigrants got along very well, and they shared their work; so it is possible that all four men, namely Brunel, Pharoux, and the Mangins, had a hand in the design of the theater. Later Alexander Hamilton hired another French emigrant, Major L'Enfant, to design the defenses of the Narrows, and L'Enfant turned much of the work over to Brunel.65 L'Enfant designed Federal Hall in New York City City, which so impressed Washington that he chose L'Enfant to be the designer of Washington, DC.66

There was a large French emigrant population in New York City City at this time. The number of French refugees increased rapidly in New York City City after the outbreak of the revolution in Saint-Domingue (Haiti) in August 1791. We know of no fewer than two French language newspapers published in New York City City in the 1790s. The first was the short-lived Journal des Révolutions de la Partie Française de Saint-Domingue of 1793. The second began publication on July 6, 1795, under the title of the Gazette Française et Américaine, with alternate columns written in French and English. On July 17, 1795, the publisher was given as John Delafond. On October 2,1795, it was bought and published by Labruere, Parisot & Co. On May 18, 1796, it changed its name to the Gazette Française and thereafter was published wholly in French. From July 2, 1797, it was published by Claude Parisot & Co., who in early 1798 published it at 21 Beekman Street. The last known issue is dated October 4, 1799.67 Brunel would not have approved of the Gazette, for it supported the revolutionary French Republic, and tried to make light of any differences between the United States and France, such as the XYZ affair. (Brunel himself was designing cannon foundries and defenses of the Narrows because the United States and France were on the verge of war.) The Gazette was rather torn; it was pro-Republican, but it was also pro-slavery, for many of its readers were slaveowners. A regular feature was advertisements for runaway slaves. It also has regular advertisements for at least one French bookshop.68 Unfortunately, it makes no mention of Brunel, Mangin, or the opening of the New York City Theatre, preferring to concentrate on news from France and the Caribbean, which is what chiefly interested its readers. They wanted to know when it would be safe to return to their homes. It would have been interesting to learn what Brunel's French contemporaries thought of him. Brunel's biographer Beamish mentions that two other French emigrés found employment at the New Theatre. A nobleman, Baron de Rostaing, acted on the stage; while a barrister, M. Savarin, played in the orchestra—turning the avocations of their past into a gainful employment.69

The important point is that there was a large French population in New York City City in the 1790s, many highly educated and talented, who provided a useful injection of skills for the young United States. The United States certainly needed architects and engineers. Many of these Frenchmen knew each other, and shared the work around.

Brunel is listed in only two years of New York City City directories; in David Longworth's directory of 1797 (published in June 1797) there is an entry for "Brunel's, manufactoy, 17 Murray Street," and in Longworth's directory for 1798 (published in June 1798) there is an entry for "Brunel's, manufactoy, 38 George Street."70 Brunel evidently tried to set up a factory in New York City City making use of some of his inventions, but soon decided he might succeed better in a more developed country, namely Britain. Britain also had the advantage that she was waging war against Brunel's own enemy, revolutionary France. A further reason to leave was the collapse of the Castorland scheme and the accidental drowning of Brunel's friend Pierre Pharoux while crossing the great falls of the Black River, up from Sackets Harbor (near what is now Watertown, New York City)71

Brunel left New York City City in 1799, carrying a letter

of recommendation dated February 6, 1799, from Alexander Hamilton to Rufus King:

This will be delivered to you by Mr. Isambard Brunell, French by birth but Anti-Jacobin by principle, and by

necessity an Inventor of Ingenious Machines. He goes to England to endeavour to

obtain a patent for one, which he has contrived for the purpose of copying. He has a passport from Mr. Liston and

I believe our Secretary of State. This letter is to ask for him such patronage as in your situation and in his may be prope.72

Brunel went to Britain to set up his block machinery, which proved invaluable to the Royal

Navy in the struggle with Napoleon. A happy side-benefit was that the Wood shavings could

be used to make hatboxes and pillboxes, and he established a factory for this purpose in Battersea in 1808, of which Brunel's

biographer Beamish writes: To these important economic advantages to the public

was added the high gratification to Brunel himself of being able to employ young children in the manufactory. The

love of the young was a distinguishing and abiding feature in Brunel's character, and now, after a few hours'

instruction and one day's practice, he had the happiness to reflect, that for a large number of these special objects of his

sympathy he

had provided the means of earning for themselves an honest and sufficient livelhood.73

The property upon which the Park Theatre was built—Section 1, Block 90—was originally known as the "Vineyards" or the "Governor's Garden." It was subsequently acquired by John White. John White was attainted and his property forfeited (presumably because he was a patriot during the Revolution; New York City was loyalist), but the property was afterward restored to his wife Ann White (widowed by February 1795) who divided the property into lots and made the early conveyances. The names of the Whites are commemorated by John Street, and one block north, Ann Street, notorious as the residence of that tooler of large cents, Smith. On April 14, 1786, Isaac Stoutenburgh and Philip Van Cortlandt, the Commissioners of Forfeiture, made a grant to Ann White of the entire block.74 The lots which became the Park Theatre are lots 6, 7, and 8. There is a map of the property surveyed by Evert Bancker on October 28, 1797, among the New York City City real property libers.75 This shows the theater as a trapezoid, with the part toward Park Row (then called Chatham Row) being rectangular, but the section on Theatre Alley (then called the Mews) being at an angle to the rest of the building. The lot runs 78 feet along Park Row, 130 feet to Theatre Alley, 85 feet southerly along Theatre Alley, and then 165 feet westerly to Park Row.76 William C. Young came across and reproduced an architectural ground plan of the theater in the collection of the New-York Historical Society, ascribed to Brunel, and this attribution seems secure: in every way I could check it, the plan corresponds to the dimensions of the lot and to what we know of how the theater looked, including the northern annex which contained the green room and other rooms for the actors. This annex is visible, to the left, on the Tisdale engraving and on the token.77

The theater sought to extend its portico to cover the sidewalk, and petitioned the Common Council for this on June 1, 1795, but its petition was rejected.78 As can be seen from the token and the Tisdale engraving, the portico as constructed remained flush with the rest of the theater. If the portico had been extended, the theatre would look rather like the buildings on the Rue de Rivoli in Paris, which have porticos which extend over the sidewalk, which may well have been Brunel's inspiration. The plan for the portico would not die, however; John K. Beekman and John Jacob Astor petitioned for it again in 1821, when they rebuilt the theater, and the Streets Committee of the Common Council rejected the plan.79 Permission to extend the portico over the sidewalk (not more than five feet) was finally granted in July 1828, to Edmund Simpson.80

The details of the property are summed up in an indenture recorded in the Real Property Files of the New York City City Register on May 16, 1850, presumably in the course of the settlementt of the Estate of John Jacob Astor, deceased. This document explains that in October 1794, Lewis Hallam and John Hodgkinson proposed the construction of a theater. Each subscriber was to put up $375, which would raise "a sum sufficient for the purposes of purchasing Ground, building a Theatre, and providing Scenery, Machinery etc. for the exhibition of Dramatic entertainments." There were 115 subscribers.81 Each subscriber could receive a free ticket plus interest at 5%, or no free ticket and interest at 7%. $42,700 was raised from the subscribers. Jacob Morton, Carlile Pollock and William Henderson were appointed the trustees. Lots 6,7 and 8 were bought from Ann White for $15,000. On January 1, 1797, because of delays in construction, the builders borrowed more money from Daniel McCormick, Joshua Waddington, John B. Coles, John McVicker and John C. Shaw. They bought from John Hodgkinson his lot for $1,750. Edward Livingstone became an additional trustee. But still more money was needed. The promoters borrowed $20,000 from the Bank of New York City for nine months at 6%; they borrowed $17,000 from the Branch Bank of the United States in the City of New York City, also for nine months at 6%. But the theatre did not make enough money to survive. Furthermore, some of the trustees either went bankrupt or died. On February 10, 1804, the property was auctioned off at the Tontine Coffee House by Thomas Cooper, Master in Chancery, and struck off to McCormick, Waddington, Coles, McVicker and Shaw for $43,000.82 They in turn sold the Theatre plus the Hodgkinson lot to John Jacob Astor and John K. Beekman for $50,000 on April 21, 1806.83

The Theatre opened on January 29, 1798, with a performance of "As You Like It." It was announced by the following advertisement:

NEW THEATRE.

THE PUBLIC is respectfully informed, the New Theater will open this evening,

MONDAY, JANUARY 29, 1798,

with an OCCASIONAL ADDRESS, to be spoken by MR. HODGKINSON

And a prelude written by Mr. Milne, called,

ALL IN A BUSTLE, Or, THE NEW HOUSE. The characters by the company. After which will be presented, Shakespear's COMEDY of

AS YOU LIKE IT.

[There followed a listing of the cast.] To which will be added, the MUSICAL ENTERTAINMENT of the

PURSE, or AMERICAN TAR.

Places for the boxes will be let every day at the old office, in John-street, from 10 to 1 o'clock, and on the

play day from 3 to 4 in the afternoon.

Tickets can also be had at the above office any time previous to Monday, 4 o'clock, after which hour they must be applied

for at the Ticket

Office, in the New Theatre.

Subscribers will be made acquainted with the mode adopted for their admission, by application at the Box Office.

The offensive practice to Ladies, and dangerous one to the house, of smoking segars, during the performance, it is hoped,

every gentleman

will consent to an absolute prohibition of.

Ladies and Gentlemen will please direct their servants to set down with their horses heads towards the New Brick Meeting,

and take up with

their heads towards Broad Way.

The future regulations respecting the taking of seats, &c. will be placed in the Box Office, for general information.

The doors will be opened at five, and the curtain drawn at a quarter-past six.

Ladies and gentlemen are requested to be particular in sending servants early to keep boxes.

Boxes, 8s. Pit, 6s. Gallery, 4s. Vivat Respublica.84

The prices are in New York City shillings, which is a very logical monetary system, because one shilling is l2 1/2 Federal cents. In Federal money, it cost a dollar to sit in a box, seventy-five cents to sit in the pit (the orchestra), and fifty cents to sit in the gallery (balcony).

Unfortunately, the contemporary newspaper accounts of the opening confine themselves to describing the interior of the theater. The only remark in the literature which helps us to determine the external appearance of the Park Theatre is the remark by Thomas Allston Brown, "in cold weather two blazing fires were kept up at either end of the lobbies"85 This corresponds to the two chimneys at either end of the building which are visible on the token and the Tisdale engraving. In terms of the overall "feel" of the building, the building which still exists today which best conveys an idea of the First Park Theatre (and of New York City City public edifices of the 1790s) is the church of St. Mark's-in-the-Bouwerie, which is an almost exact contemporary: it was begun in 1795 and consecrated in 1799. (The steeple and the porch are, however, nineteenth century additions.)86

Beamish says that when the theater opened, Brunel constructed a mechanical windmill, in which he and a friend hid; the windmill appeared on stage, and the friend then recited various satires, which revealed an intimate knowledge of the foibles of New York City society. An uproar ensued, and the audience advanced to destroy the windmill, but Brunel maneuvered the machine over a trapdoor, down which he and his friend descended, and they departed that night for Philadelphia.87 Unfortunately, this incident is recorded by none of the American theater histories (such as Odell), which are otherwise very detailed. If this incident did take place, it must have occurred on some night other than January 29, 1798.

Even when it opened in January 1798, the theater was still in an unfinished state. It was only in November 1798, when the theater reopened—its opening was slightly delayed because of a yellow fever epidemic in New York City—that the interior dome was finished by Charles Ciceri, the great scene painter of his day.88

The theater was first called the New Theatre,89 and was on Chatham Row, which led to Chatham Square (named for William Pitt the Elder, the Earl of Chatham, who had had the Stamp Act repealed). It was in a part of the city where everything unwanted had been put: the prison (Bridewell), the Alms House, and the graveyard for African-Americans. This was partly because of the insalubrious swamps surrounding the Fresh Water Pond (Foley Square continues to flood regularly even today). Development was further delayed by the uncertain title to this area, because John White, the landowner, had had his property declared forfeit during the War of Independence. By the 1790s, however, the rest of New York City City had become too built up, so that the only large lots remained in this area to the north of the city. New York City Hospital was built there in 1791, followed by an insane asylum in 1808, which later moved to Bloomingdale (now Columbia University). The construction of City Hall and the development of City Hall Park (with fountains courtesy of the New York City Waterworks) dramatically changed the part of the neighborhood close to Broadway, making it quite fashionable; the area further to the northeast, which flooded, remained notorious as the "Five Points" slums.90 When City Hall Park was developed in the first decade of the nineteenth century, the theater began to be called the Park Theatre and the name of its street was changed to Park Row. At some point, probably before 1806, a remodelling of the outside took place, which eliminated the pilasters. Another addition was a statue of Shakespeare which was set up in the central niche (converted from a window) on the second floor. By 1806, the exterior was very plain, because when the interior was remodelled then by Mr. Holland, the New-York Evening Post praised the interior highly, but added, "We speak of the interior only, for the outside remains just as it was, a standing libel on the taste of the town"91 This simplification of Brunel's design is probably the origin of Ireland's remark, that "It is doubtful if they [Brunel's plans for construction] were ever carried out—that for the exterior, which included a range of fluted pilasters by way of ornament, certainly was not, and for many years the front wall remained perfectly plain and barn-like in appearance"92 This is not correct. The basic design was faithful to the plans of Brunel in its number of stories and windows. The pilasters must have existed at one time, because they are depicted in the Tisdale engraving and independently confirmed by the Milbourne painting. The plainness remembered by Ireland in the 1850s was probably the result of a remodelling done before 1806.

The Theatre had a huge seating capacity—about 2,000. After the theater was remodelled and reopened in 1807, the New-York Evening Post gave the suspiciously accurate figure of 2,372.93 This is about the size of Avery Fisher Hall. The audience in the pit and the gallery did not sit in individual chairs at this period, but rather on backless benches; anyone who has sat in the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford will have a good idea of the seating arrangements of a seventeenth and eighteenth century theater.94

The audience did not spend the entire evening sitting on these uncomfortable backless benches. The programs were very long by modern standards, with two plays an evening, lasting from 6:30 or 7 until 10:30 at night; the texts of the plays were often cut in a quite arbitrary fashion. The lights were not turned out in the auditorium (the Park was only lit by gas after 1827) and the audience could and did wander about, only returning for the great set pieces. Italian opera in this period took account of this foible, including arie di sorbetto, during which the audience could go out for ice cream.

It was very difficult to fill this huge theater; the total population of New York City City (Manhattan only) in 1800 was 60.489,95 which meant the theater could contain 3.3% of the population of the city. In other words, if the theater staged one play for over a month to packed houses, every man, woman and child in the city would have seen it. For a time William Dunlap had some success with his translations of the German playwright (and Russian agent) August von Kotzebue, but Dunlap ended a bankrup.96 Stephen Price, who eventually succeeded Dunlap, filled the theater by resorting to the blockbuster, the star system, importing big names from Europe such as George F. Cooke (November 1810) and Edmund Kean (1820). In 1811, Cooke appeared as Lear at the Park Theatre, opposite John Howard Payne as Edgar.97 At a very early date in New York City City the inhabitants were seeing world class actors. Both Cooke and Kean were over the hill when they came to New York City, having abused alcohol for far too long, but they gave some brilliant performances. Odell has criticized Price for this, saying that the star system destroyed healthy stock companies in New York City City, but it seems unlikely that Price could have filled his theater otherwise. The size of the theater dictated what he had to show.

The one event at the Park Theatre which I would have liked to see was the first New York City performance of Mozart's Don Giovanni on May 23, 1826, with Manuel Garcia's company, including Maria Malibran in the role of Zerlina. What made this performance remarkable is that it was done at the urging and in the presence of the librettist, Lorenzo Da Ponte, who, having proven himself too disreputable for Venice, Vienna, and London, had to live out his final years in New York City City.98

The bustle around the Park Theatre at nighttime was a great annoyance to the neighbors, who complained about parking problems. On December 18, 1815, the neighbors to the theater complained to the Common Council about the hackney carriages parked on their streets when plays were on at the Park Theatre.99

Astor's purchase in 1806 was dictated more by his love of the theater than his sense of profit; in fact, it was an unusual departure from his normal method of property investment, which was to buy vacant lots. It is said of Astor that he "seldom missed a good performance in the palmy days of the 'Old Park'," and even on the evening he learned that his ship the Tonquin had been lost, he still went to the theater, not wishing to abandon his favorite evening's amusement. Thomas A. Cooper, an actor whose best part was Macbeth, leased the theater from Astor for $2,100 quarterly, which he found difficult to pay, so that his surety, Stephen Price, was often called to make up the deficiency. In September 1814, Price told Astor that he would have to give up the theater unless the rent was reduced, arguing that he could get out of his lease because of the War of 1812. Astor refused to consider it.100

Fire is always a danger in theaters, and the Park Theatre was attacked by several fires. The Common Council was

aware of this danger, and in 1803, established Fire Engine House Number 4 in a room at the northeast corner of the theater,

depositing 30

buckets there.101 At one in the morning on May 25, 1820, a disastrous fire burned the First Park Theatre to the ground, and was thus described

in the

New-York Evening Post: Fire—Just before one o'clock this morning, our inhabitants were alarmed by the

dreadful cry of fire, and it was soon apparent, from the tremendous glare of light that reached to the most remote parts of

the city, that

it proceeded from some building of uncommon size; which proved to be the Theatre. No effort could check its progress, nor

was it possible

to do any thing more than stand by, and witness the complete destruction of the building, and almost every thing it contained.

After all

the enquiries that have been made it is impossible to tell precisely the manner in which it originated. It has, however, been

satisfactorily ascertained, that the first appearance of the fire was near the ridge of the southeast corner of the roof,

and it could not,

therefore, have arisen from any fireworks employed in the course of the entertainments of the early part of the evening, as

has been, by

some, erroneously supposed. Nor is there the least grounds to suppose that it was designedly set on fire, but it must have

been owing to

accident or negligence.

The person, whose constant business it has been for some years, to see every thing is safe, by going about the house from

top to bottom,

after everyone has departed, once before and once after every light is extinguished, had performed that duty last night, as

usual, and lain

down on his bed in his clothes, from which he was rous- ed by the crackling of the fire, and looking up saw the blaze just

making its appearance at the place we have mentioned.

We learn that there was no insurance on the building, and but a partial one on the scenery or other property. The most distressing

loss

falls upon individuals connected with the establishment, whose number we understand to be not less than 200 persons, including

mechanics

and laborers.102

John Jacob Astor at once had the theater rebuilt. This altruistic gesture failed to impress at least one of the wits of the town, who wrote in the New-York Evening Post :