The commercial relations of Byzantium with the West during the early mediaeval period have been the subject of many historical studies such as those of Henri Pirenne and Alfons Dopsch. As the older view of a catastrophic break in the stream of civilization during the period of the barbarian invasions was relegated to the history of historiography, the importance of the economic changes of the early Middle Ages assumed greater and greater significance. It is, of course, true that most of the scholars who have attempted discussions of the history of this period have made some use of the numismatic material available to them, but they have in no sense exhausted the information that may be derived from that source. In the study of the early Middles Ages numismatics has been used largely as illustrative material to support conclusions based primarily upon the literary sources. The archaeological and numismatic studies have therefore not served their true function as ancillary sciences of history. Many reasons for this situation are immediately evident, if a summary perusal is made of the secondary literature in those fields and the training of most mediaevalists is considered.

This book is not designed to cover this tremendous gap in historical scholarship, but it is an attempt to indicate that certain facts which may be derived from the numismatic and archaeological data are vital to a complete synthesis of the historical material. It is no longer possible for a mediaevalist, anymore than for an ancient historian, to relegate the vital ancillary sciences to the field of antiquarianism. From the deductions based on the results of archaeological and numismatic study of the remains of the early mediaeval period a new view of that epoch may be constructed which will encompass the literary evidence as well.

This book itself, however, did not begin as an attempt to correct this woeful lack of utilization of numismatic evidence. While I was working on a much larger study on the subject of Byzantine monetary policy from Diocletian to Heraclius, it soon became evident that the light weight gold currency, which had received passing interest from numismatists but was generally ignored by historians, was really deserving of a much more intensive treatment. No successful attempt had been made to integrate this unique series of gold coins into the economic history of the sixth and seventh centuries. The amount of material at the disposal of a researcher had grown considerably in recent years, and several men of stature in numismatic studies had begun to collect data on these pieces. A fair number of site finds and hoards were known which had a direct bearing on the problem, and the general situation had never been so favorable for an attempt at a solution. In addition the American Numismatic Society was very fortunate in securing the participation of Mr. Philip Grierson of Gonville and Caius College of Cambridge University for the Summer Seminar in Numismatics of the year 1954. The opportunity to discuss the many problems which naturally arose in connection with this study with a man of Mr. Grierson's stature in numismatic studies was most fortunate. Mr. Grierson's help was invaluable for a number o reasons not the least of which was the fact that he placed all of the photographs of the gold coins in his own collection as well as those of the light weight solidi which he had encountered in the course of his own studies at my disposal. Mr. Grierson also analyzed his own coins by the specific gravity technique, and thus he made available data which was previously unknown. For all of these things and most importantly for his willingness to discuss individual problems, I wish to acknowledge a deep sense of gratitude to Mr. Grierson.

Since my own training has been in history, it was, of course, vital that there be some scholar who would aid me in the purely technical aspects of numismatics. In this capacity Mr. Louis C. West of Princeton University and President of the American Numismatic Society has been of invaluable assistance. The most technical aspects of this work have been perused by Mr. West, and many of his suggestions have been incorporated into this book. If there is any merit to be found in that aspect of this work, it is largely the result of the aid and counsel of my teacher, Mr. West, who introduced me to the value of numismatic study while I was a graduate student and has done so very much to encourage my researches.

Sole responsibility for the hypotheses and historical explanations put forward in the course of this book must rest with me, but the debt which is owed to my teachers, Professor Theodor E. Mommsen of Cornell University and Professor Joseph R. Strayer of Princeton University, cannot be calculated. Both of them very kindly consented to read the manuscript, and their suggestions have been incorporated into the finished product. The techniques and methods which were utilized in the work were learned in the seminars conducted by them, and my interest in this field of historical research is the result of many most enjoyable hours spent stuying under their tutelage.

This book, however, would have been impossible without the aid of so many scholars who sent me casts or photographs of coins and notes regarding these pieces. Among these should be numbered Dr. Theodore V. Buttrey, Jr. of the Classics Department of Yale University who secured photographs of the coins in the Hermitage through the help of Dr. L. Belov of the staff of the Hermitage, and who also managed to obtain photographs of the coins in the Poltawa Museum of Regional Studies from the manager of that museum, Dr. V. T. Shevtshenko. Dr. Buttrey's kind efforts, however, extended even further, and with his help and the assistance of Dr. Maria R. Alföldi and Dr. L. Huszár, Keeper of Coins and Medals of the collection in Budapest, casts of all of the light weight pieces in that collection were also secured. In addition the aid and assistance of Mr. R. A. G. Carson of the Department of Medals and Coins of the British Museum, M. Jean Babelon, Conservateur en chef du Cabinet des Médailles of the Bibliothèque Nationale, Dr. E. Erxleben of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Dr. A. N. Zadoks-Jitta of the Royal Cabinet in the Hague, Dr. W. D. Van Wijngaarden of the Rijksmuseum Van Oudheden te Leiden, Dr. K. Kraft, Konservator of the Staatliche Münzsammlung in Munich, Dr. Eduard Holzmair of the Bundessammlung von Medaillen, Münzen und Geldzeichen in Vienna, and Mr. Enrico Leuthold of Milan have been most important. The grateful thanks of the author for all of the specimens, many of them unpublished, furnished by these scholars cannot be expressed in terms forceful enough to convey the full extent of the debt owed to them. My sincere thanks are also due to the authorities of the Museum in Nicosia, Cyprus, for permission to publish Coin no. 79a.

It is to the unusual specimens in coinage that the historian is most often drawn in his search for new information regarding the past. The continued repetition of older types without any seemingly significant alteration is not likely to catch the eye of the scholar, nor is it probable that it will excite a great deal of discussion or interest. Perhaps this is in part the explanation for the fact that a rather surprising series of solidi which are to be distinguished primarily on the basis of the marks in the exergues have received only passing numismatic comment and have never been adequately studied from the historical point of view.

When it is remembered for how long a period of time the study of coinage has fascinated men of culture it is strange to note that it was only in 1910 that a scholar commented upon the series of light weight solidi with unusual exergual markings. Dr. Arnold Luschin von Ebengreuth, in his study of the denarius of the Salian Law, made use of the fact that such a series of light weight solidi marked BOXX existed.1 He was, however, aware of the existence of only a few of these pieces, and the entire scope of the problem was not evident to him. Only a few emperors, Justinian, Justin II, Phocas, Heraclius during his sole reign, and Heraclius and Heraclius Constantine during their joint reign, were represented on the solidi that he studied.

It is, of course, true that a certain number of these light weight Byzantine gold pieces had been reported in sale catalogues on several occasions prior to the date of Luschin von Ebengreuth's study, and also it is true that Sabatier as well as Wroth had noted the existence of a few specimens of this series, but there was still no body of material collected which warranted any study of the series itself. Luschin von Ebengreuth could use these coins in his study of Frankish coinage and the Salian Law to indicate a Byzantine adumbration of the subsequent decline in the weight of the Frankish solidi and trientes, but he could derive nothing from them regarding the policies of the Byzantine emperors whose names appeared on these strange pieces.

By 1923, however, enough material had been collected to make it possible for Ugo Monneret De Villard to write the first numismatic study devoted solely to the light weight solidi.2 In the intervening period a series of finely written and well illustrated sale catalogues which included a number of such coins had appeared, and the monumental Byzantine coin catalogue of Count Tolstoi had been published. Thus it was possible for Monneret De Villard to discern the true limits of this series of solidi, and though the catalogue which is included with the present study is more than three times as long as that of Monneret De Villard nonetheless the first truly significant collection of the numismatic data was made by him.

From a search of all of the literature available to him and from research in the various major museums of Europe, he discovered that there was not one series of light weight solidi, but rather that there were several series of such coins each bearing a different set of markings in the exergue on the reverse. It was also evident, when the material had been gathered, that these light weight coins were not issued intermittently by several emperors of the sixth and seventh centuries, but rather that they formed a series which extended in unbroken fashion from the reign of Justinian to that of Constantine IV Pogonatus.

As a result of this numismatic inquiry into the nature of these coins Monneret De Villard concluded that there were at

least seven different varieties of markings that appeared in the exergue on the reverses of Byzantine solidi which would indicate

that the coins

in question were light. Unfortunately he did not distinguish between the authentic Byzantine gold pieces and those of barbarian

manufacture. His

list of markings would therefore be somewhat smaller if it were devoted only to the genuine Byzantine coins. The marks as

he listed them,

however, were i) OB⁕+⁕, 2) OB XX or OB·XX, 3) OB or OB+⁕, 4) BOXX, 5) BOГK, 6) CXNXU, and lastly 7) CX+X÷. The

weights of almost all of the coins bearing these marks in the exergue were clearly below the lowest weights which one might

reasonably expect

from solidi which had originally been struck at full weight. Of all the markings listed, however, Monneret De Villard

felt that only two series could be grouped in which he was possessed of a sufficient number of weights to postulate any hypothesis

regarding the

theoretical weight at which these coins had been struck. The forty-two coins which were contained in groups two and four he

considered as one

series. This he might logically do because there was nothing more than a transposition or metathesis of the first two letters

of the exergual

mark involved in distinguishing them from one another. These coins when considered as a single series showed an average weight

of 3.657 grammes

according to his calculations. A second series of coins, he felt, might be constructed of those coins which had the exergual

marks in groups one

(OB⁕+⁕) and three (OB+⁕).3 The three coins that were listed with the mark OB⁕+⁕ had a mean weight of 3.866 grammes,

while the nine coins with the mark 0B+⁕ had an average weight of 3.96 grammes according to the calculations of Monneret De

Villard.4

or OB+⁕, 4) BOXX, 5) BOГK, 6) CXNXU, and lastly 7) CX+X÷. The

weights of almost all of the coins bearing these marks in the exergue were clearly below the lowest weights which one might

reasonably expect

from solidi which had originally been struck at full weight. Of all the markings listed, however, Monneret De Villard

felt that only two series could be grouped in which he was possessed of a sufficient number of weights to postulate any hypothesis

regarding the

theoretical weight at which these coins had been struck. The forty-two coins which were contained in groups two and four he

considered as one

series. This he might logically do because there was nothing more than a transposition or metathesis of the first two letters

of the exergual

mark involved in distinguishing them from one another. These coins when considered as a single series showed an average weight

of 3.657 grammes

according to his calculations. A second series of coins, he felt, might be constructed of those coins which had the exergual

marks in groups one

(OB⁕+⁕) and three (OB+⁕).3 The three coins that were listed with the mark OB⁕+⁕ had a mean weight of 3.866 grammes,

while the nine coins with the mark 0B+⁕ had an average weight of 3.96 grammes according to the calculations of Monneret De

Villard.4

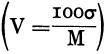

The three mean weights which had been obtained by this process were all well below what might be expected of solidi which had originally been struck at full weight. Theoretically and actually the solidus had been struck al-pezzo at 1/72nd of a Roman pound. This fact was attested from the legal texts in the Theodosian and Justinian Codes as well as from the marks of value which were found on certain of the earlier solidi. Luschin von Ebengreuth had also demonstrated most scientifically that one could hardly expect a weight of less than 4.35 grammes for any undipped solidus. This is in accord with our knowledge concerning the weight of the Roman pound. It is now generally conceded among numismatists that the solidus must have been struck at a theoretical weight of 4.55 grammes and that the siliqua ami was theoretically 0.1895 grammes.5 Monneret De Villard, however, had adopted the weight of the Roman pound which Naville had calculated6. According to the system set forth by Naville the Roman pound weighed 322.56 grammes, and the siliqua ami, which it is quite certain was 1/1728th of a pound, was 0.1867 grammes. Since there were twenty-four siliquae or four scruples in the normal solidus of 1/72nd of a pound, the theoretical weight of the solidus, according to Naville, would be 4.48 grammes. It can be seen immediately that there is only the slight difference of seven-hundredths of a gramme between the theoretical weight of the solidus as calculated by Naville and that according to the traditional view.

Sixty coins were listed in the article by Monneret De Villard according to the rulers and with notations regarding the peculiar markings in the exergue on the reverses. When, however, the coins were grouped according to the marks in the exergues it was found that only in one instance, those inscribed BOXX and the like, was there really a sufficient number of coins to warrant an attempt at a scientific treatment. In another case, that of the coins marked OB+⁕, only some hypotheses could be put forward.

Unfortunately Monneret De Villard did not make use of the frequency curve method of statistical analysis of the metrological data which he had accumulated, but he resorted to the less scientific, and therefore more uncertain, practice of calculating mean weights. As a result he was only able to discuss with any degree of confidence those coins which he had assembled in his first group, a total of forty-two specimens.

Monneret De Villard concluded that the solidi of this first series, i.e., those with a mean weight of 3.657 grammes were struck at twenty siliquae to the solidus (theoretical weight according to Naville's system of 3.734 grammes). He was aware of the fact that the siliqua was mentioned several times in the Edictum Rothari as well as in the Capitula Extravagantia of the Lombard laws,7 and he found, as Brunner had noted much earlier, that in the Glossarium Matricense 63 it was stated that Siliqua vicesima pars solidi est, while the Glossarium Cávense 104 and 163 asserted Siliquas. Id. vicesima pars solidi and Silicuas, id est vicesima pars solidi, ab arbore, cuius semen est, vocabulum tenens.8 Monneret De Villard held that since the glossators themselves believed this valuation of the solidus at twenty siliquae it indicated quite clearly that they knew that it corresponded to the actual worth of the solidi which circulated during the reign of Rothari (636–652 A.D.). The reign of Rothari, moreover, was roughly contemporary with that of Heraclius, and the greatest number of light weight solidi were struck with the name of Heraclius imprinted on them. From these facts and premises Monneret De Villard concluded that the light weight solidi of twenty siliquae were actually referred to in contemporary texts and probably were a part of the monetary system.

In doing this, however, he erred most seriously, probably because of the fact that his training was that of a numismatist and not ahistorian. His use of the legal texts does not meet the requirements of historical technique. The Edictum Rothari, it is true, was issued in 643 A.D. during the reign of that Lombard king, and the Capitula Extravagantia are attributed to either the reign of Grimoald (662–671 A.D.) or Luitprand in the first half of the eighth century. The word siliqua does occur in both cases, but it is not defined within the text but only in the two glosses that have been quoted. The glosses which are cited by Monneret De Villard in support of his position that these siliquae were the twentieth part of the solidus are more recent than the legal texts themselves. They may safely be put into Carolingian times or later, when the solidus in western Europe was uniformly valued at twenty siliquae. The two manuscripts in which these glosses occur are related in the stemma. They come from a common source.9 That source seems to be a relatively late one, and these texts are more valuable for the later period of Lombard law. The Codex Matritensis regius D 117 was probably written in the region of Beneventum or Salerno in the tenth century.10 While the Codex Cavensis was most likely produced in the region of Beneventum about the year 1005 A.D. 11 It is probable that the glossator himself was a Beneventan of about the same period.12 The actual text of the glosses is apparently derived from Isidore of Seville (ca. 560–636 A.D.), but Isidore retains the older valuation of the solidus at twenty-four siliquae.13 Perhaps, as is most likely, the influence of the Frankish monetary system was the stimulus for the lower valuation of the solidus among the Lombards.14 When this change was accomplished, however, must remain uncertain. It is quite definite that the glossators referred to by Monneret De Villard were not giving us exact information regarding conditions in the time of Rothari and Grimoald, but rather that they were utilizing the valuations known in their own time. The glossators’ knowledge of the monetary system in force during the reign of Rothari was very likely much less than that available to numismatists and historians today. In addition these glosses can hardly be used to prove that the Byzantine government issued such light weight solidi for normal circulation within the Empire during the seventh century, since they are derived from a later period and they comment on a matter of Lombard and not Byzantine law.

In studying the second group of coins, those marked OB⁕+⁕ and OB+⁕, Monneret De Villard found himself seriously

hampered by an insufficiency of data. Three coins marked OB⁕+⁕ had an average weight of 3.866 grammes, and the nine pieces

marked OB+⁕ had a mean

weight of 3.96 grammes. This seemed to indicate a theoretical weight of approximately twenty-one siliquae which should have

corresponded to 3.92

grammes according to the system worked out by Naville and accepted by Monneret De Villard. If

this were so, then Monneret De Villard suggested that the mark which he transcribed as-⁕ might be explained as — +⁕,

and that the two X's would thus be combined into the single sign ⁕. The total would then be twenty-one. Unfortunately such

an explanation is

hardly satisfactory because, as will be shown, there are no solidi marked -⁕, and, furthermore, the coins marked OB⁕+⁕ and

those marked OB+⁕ or

OB all belong to a single group. The marks OB+⁕ and OB

all belong to a single group. The marks OB+⁕ and OB are merely

abbreviations of OB⁕+⁕. These asterisks cannot therefore be taken as the combination of two X's or the total would be in excess

of forty rather

than twenty-one.

are merely

abbreviations of OB⁕+⁕. These asterisks cannot therefore be taken as the combination of two X's or the total would be in excess

of forty rather

than twenty-one.

These solidi, however, were supposedly struck at approximately 3.92 grammes or about 1/84th of a Roman pound.15 Monneret De Villard, following Luschin von Ebengreuth, pointed out that some of the pseudo-imperial solidi struck in Gaul during the early Merovingian period were issued at approximately the same average weight.16 Some of these Frankish gold pieces were issued with imperial portraits and they bore marks of value, XXI in the case of the solidi and VII in the case of the trientes. These Frankish coins will be examined more closely at a later point, but it should suffice for the present merely to indicate that the existence of such coinage from mints in southern Gaul is well attested.17

There was also a certain amount of literary evidence that bore on the question of such light solidi which weighed less than 1/72nd of a pound, and Monneret De Villard dealt with a small portion of that evidence. He cited a Novella of the Emperor Majorian in which that Emperor required that all solidi of full weight be accepted by the tax collector with the one exception of the Gallic solidi, the gold of which was of lesser value.18 This legal text was issued in 458 A.D. and therefore precedes the issuance of the peculiar series of light weight soUdi in which we are interested by at least eighty years and possibly as much as a century. That the Romans had certain problems connected with the unofficial striking of solidi of light weight during the fourth and fifth centuries cannot be doubted in view of the extant laws regarding gold coins, but these laws cannot be used to indicate that an imperial gold coin was struck at a lighter standard. The entire body of literary evidence will be discussed at a later point, but it should suffice for the present merely to point out that the particular Novella just cited cannot refer to the light weight solidi which form the subject of this book.

In addition to that Novella, however, Monneret De Villard refers to several other documents which should be treated in connection with a critique of his work. One of the documents to which reference is made is the so-called Formula Lindenbrogiana LXXXII, but this can easily be shown to be a spurious reference because of the variants.19 Two other instances in which the so-called solidus Gallicus is mentioned are known from the correspondence of Gregory the Great, and Monneret De Villard also makes reference to them. In one letter Gregory speaks of the solidi Galliarum, qui in terra nostra expendi non possunt, apud locum proprium utiliter expendantur.20 In another letter of Gregory to Dynamius, the Patrician of the Gauls, the sum of four hundred Gallicanos solidos is mentioned.21 These references to the solidi Gallici can easily be explained on the basis of the Frankish coinage which was truly light weight in the last decade of the sixth century and could not be used within the confines of the Byzantine Empire.

Monneret De Villard, however, recognized that his case was all too weak when bolstered only by references to the coinage of Gaul which Luschin von Ebengreuth had already proven to be of light weight in the last two decades of the sixth century. This Frankish coinage had been adopted after Justinian had instituted the striking of light weight solidi. As a final bit of literary proof that light weight solidi of approximately 1/84th of a Roman pound were issued by the Byzantine government Monneret De Villard cited a law of Valentinian I of the year 367. This law, he maintained, stated explicitely that a solidus of 1/84th of a Roman pound was known to the Romans. That law may be translated as follows:

On account of the mining tax, for which the custom peculiar to it must be retained, it is determined that fourteen ounces of gold dust be brought for each pound (of metal).22

This law clearly does not mention the striking of solidi at 1/84th of a Roman pound. It simply insists that mine operators in the fulfillment of their leases should continue an older practice of remitting to the Treasury fourteen ounces of gold for each pound. This law was inserted into the chapter because it formed part of a longer law which in another section established the fact that in payments made in gold bullion a pound was to be valued at seventy-two solidi. Since such a regulation would have meant that the treasury would lose money on its gold leases, a specific exception was made in the case of the mine operators. In the fulfilling of mine leases a heavy pound of fourteen ounces was to be used as in the past, but in all other cases seventy-two solidi were to be accepted as equivalent to a full pound of gold.

The acceptance of such a heavy fourteen ounce pound, of course, requires somewhat more proof than has just been set forth, and we must therefore diverge slightly from the central theme of this chapter. A situation in which two pounds of different weights, both recognized legally, existed need excite no surprise, but great care must be taken in citing passages in this connection to distinguish the second variety of pound (i.e. that of fourteen ounces) from the mere use of heavy weights. This latter practice was common in the early mediaeval period, and there was a good deal of legislation against it.23Some passages are capable of an even wider interpretation. On the estates of the Church in 591 A.D., it would appear as if 73 ½ solidi were exacted for a pound, but that Gregory the Great considered this sinful and ordered that the rustics pay only a pound of seventy-two. In doing this, however, he states, "and there ought to be exacted neither any farthings (siliquae) beyond the pound, not a greater pound, nor charges above the greater pound, but each according to your assessment there should be an increase of the rent in proportion as the resources suffice, and so a shameful exaction may never be made."24

It is clear that the pound was not eternally the same weight, and just as we may speak of the pound Troy or the pound avoirdupois but in common parlance understand one pound to be meant, so it must have been among the Romans. A gift of 1,600 pounds of gold for the Decennalia of the emperor was voted by the Senate in 385 A.D., and that it was to be paid in the urban standard, i.e. a different one from the normal one, is carefully stipulated.25

Monneret De Villard, on the basis of the passages which have been discussed, wrongly concluded that he had demonstrated, both from the texts and the coins themselves, that different solidi struck on three different standards were in use in the Byzantine Empire during the sixth and seventh centuries. There was the normal solidus of twenty-four siliquae or 1/72nd of a pound, a lighter solidus of twenty-one siliquae or approximately 1/84th of a pound, and the lightest solidus of twenty siliquae or approximately 1/86th of a pound.26 He even went so far as to suggest that there might be still other solidi of different standards and that the study of Greek papyri from Egypt revealed the existence of a number of different solidi. The very apparent difficulties that would have arisen in the economic life of the empire as a result of such a virtually haphazard system of coinage were ignored by Monneret De Villard. Of course, it is now clear as a result of the work of Johnson and West that the calculations in the Egyptian papyri do not support the existence of solidi struck on different standards, but that they make use of a system of accounting which is now comprehensible.27

In evaluating the work done by Monneret De Villard one might, as a result of the rather loose use of texts, easily overlook the significance of the fact that his was the first attempt at establishing the true limits of the problem and applying historical data to it. A substantial catalogue of the light weight solidi had been prepared, and the problem of explaining and interpreting the significance of their existence was now clear to all. The years immediately following witnessed a growth in interest in these strange coins, and even the famed Professor Regling spoke of doing some work on them.28 Unfortunately Regling never did manage to produce the article or book, but it was a clear sign of growing interest. Hoards of these pieces and individual coins from stray finds began to appear with some frequency. The entire subject of the quantity of gold in circulation and its movements came under scholarly survey in 1933 when Professor Marc Bloch wrote a stimulating article on the problem of gold in the Middle Ages.29

In 1937 another study devoted to these light weight solidi appeared in which the author, Friedrich Stefan, put forth a new interpretation.30 A hoard of coins was found at Hoischhügel (Maglern-Thörl) which contained one solidus of Justin II which weighed only 4.07 grammes, and was therefore apparently only equivalent to twenty-one siliquae instead of the more normal twenty-four. This coin bore in the reverse exergue the mark COX+X which Stefan interpreted as meaning twenty siliquae (XX) plus one siliqua (I). The CO he expanded as Constantinople.31

The existence of this singular piece in a hoard that he was studying led Stefan to survey the entire problem. He proceeded to collect the locations of the known finds of these light weight solidi, and from that data he concluded that all of these solidi fell into two groups. Firstly, there were those coins which had been found, according to Stefan, in southern France and in Italy, and, on the other hand, there were those coins which were found in the Balkan peninsula and southern Russia. Unfortunately Stefan did not publish a list of the find spots upon which this conclusion was based, but he indicated very clearly that he believed that there was such a series of finds in southeastern France.32 Intensive and determined research has failed to yield any of the finds of light weight solidi of clearly imperial origin from southern France. No support can therefore be found for the basis of Stefan's contention.

Nevertheless Stefan believed, on the basis of his examination of the extant material, that all of the coins which might have been included in the western group were imitations of the solidi of Ravenna which had been struck in the reigns of Justinian I, Justin II, Maurice Tiberius, Phocas, and Heraclius. He maintained that they showed the characteristic stylistic marks of Ravenna and that the lightness of the coins was usually indicated by either a sloping cross (X) or a standing cross (+) in the reverse exergue. Many of them he thought could be identified by their thinness or the smaller module or smaller portraiture. The exergual marks on these coins would be COX+X or CONX+X or OBXX or rarely BOXX, and in some cases they were unmarked. The COX+X and CONX+X pieces he thought were of twenty-one siliquae and weighed about 3.78 grammes. He did not distinguish any of the solidi as being barbarian imitations, and it therefore seems likely that he never examined the coins themselves. Many of them, particularly those marked COX+X and CONX+X, are clearly of barbaric origin. Stefan, however, as has been said, merely ignored this feature and pointed out the fact that solidi of twenty siliquae issued in the names of Justinian, Justin II, Maurice Tiberius, etc., were known from Gaul, and that there was even a series of royal Frankish solidi which bore the mark XX to indicate a value of twenty siliquae. The hoard of Wieuwerd, which contained two light weight solidi of imperial origin, he contended showed that such light weight solidi circulated in the lands west of the Rhine while the fact that the use of these coins spread across the Rhine to the other Germanic tribes could be shown from the find of a barbaric imitation of a light weight solidus marked X+X and struck in the name of Justin II which was found in Grave no. 1 at Munningen in Bayrisch-Schwaben.33 He admitted, however, the he could not determine whether or not the southern Gallic mints were the source of all so-called western type solidi of the light weight series.

Turning his attention to the series which he had denominated as eastern in origin, Stefan said that though this latter series showed great similarity to the western coins they were more characteristic of the Constantinopolitan productions. The typical marks of the coinage of the Exarchate of Ravenna were lacking on this eastern series. It was also a more extended series in that it began with Justinian and extended through the reigns of Justin II, Tiberius Constantine, Maurice Tiberius, Phocas, Heraclius as sole ruler as well as in his joint reign with his son Heraclius Constantine, and so on through the reigns of Constans II and Constantine IV Pogonatus. Another point of distinction between the two series lay in the fact that all of the coins of eastern origin bore marks of value in the exergue on the reverse while some of those in the West did not. Those in the East of twenty-one siliquae of the period from Justin II through the reign of Phocas were marked ⁕+⁕ or+⁕ (⁕–⁕ or –⁕).34 The pieces of this eastern series which Stefan thought were of twenty silique occurred only for the reigns from Heraclius through that of Constantine IV Pogonatus and bore marks similar to those found in the West, i.e. OBXX, BOXX, or BOГK. The most numerous group of coins of the light weight type was that composed of those pieces of supposedly Constantinopolitan fabric of twenty siliquae with the marks of value OBXX and BOXX which were struck in the names of Heraclius and Heraclius Constantine. Stefan maintained that these coins, since they showed the head of Heraclius Constantine in smaller size than that of Heraclius, could be distinguished from the Ravennese series which showed both heads in approximately the same proportions. Monneret De Villard had listed nineteen such pieces while twenty-seven solidi of the three emperor type of Heraclius had been found in the hoard of Pereschtschepino in 1912, and in that of Novo Sandsherovo or Zatschepilovo, found in 1928, seven more had been recovered. Both places were in the district of Poltawa in southern Russia.

N. Bauer in presenting the material from these finds in 1931 had suggested that perhaps the coins had been struck in a mint in southern Russia on the northern coast of the Black Sea.35 He was, however, very cautious in proposing this and made certain to indicate that it was based solely on the location of these hoards and one other from the Dnieper Delta and not on a stylistic study of coins from other collections. Stefan went somewhat further and contended that since the solidi of the eastern series which he had classified were struck in imitation of coins of Constantinopolitan manufacture, they must have been issued at a site which was clearly under the influence of the capital. Two finds from the Balkan peninsula were used to support his view. The Sadowetz hoard in the district of Plevna had yielded a coin of Justin II of twenty-one siliquae which, in addition to the eastern mark OB⁕+⁕ in the exergue, bore the letters ΘS at the end of the reverse legend while another similar coin which was marked CO⁕+⁕ had appeared in another find from an uncertain location in the Balkans. Tolstoi had described still another solidus of the same variety as the last in his catalogue. Stefan put forth the hypothesis that the S at the end of the reverse legend stood for the sixth officina and that the Θ was the mark of the mint of Thessalonica. This suggestion was not a wholly original one, for it was discussed by several compilers of earlier catalogues.36 Since the theta was seen to occur only on those coins which Stefan recognized as of eastern origin and those same pieces supposedly showed strong signs of Constantinopolitan influence, Stefan felt that his conclusion that Thessalonica was one of the sources of the coins of the so-called eastern series was assured. In the course of a later discussion of these pieces it will be demonstrated that this is in error and that these pieces were actually struck in Antioch.

Just as the coins of the western series were carried through the channels of commerce, those of eastern origin, according to Stefan, found their way into Germany and were used as money or as pieces of jewellery and were even subject to imitation. In support of this he listed evidence from funerary deposits collected by Joachim Werner from Mullingsen in the district of Soest, from Wonsheim in the district of Alzey, from Sinzig in the district of Ahrweiler, and from Pfahlheim near Ellwagen.37 In all of these instances pieces of twenty siliquae marked OBXX or BOXX struck in the names of Heraclius and Heraclius Constantine were found. Finally, Stefan viewed a ece of barbarian origin from an Alemannic grave with the mark XVOX in the reverse exergue as an imitation of these light weight solidi of Heraclius and Heraclius Constantine.38

As a result of Luschin von Ebengreuth's study of the light weight Frankish solidi it was clear that the Byzantine light weight gold pieces were in circulation in the West by 582 A.D. By referring to two passages from the Anecdota of Procopius in which that author speaks of the lowering of the value of the gold coins by Justinian,39Stefan concluded that the Emperor struck his newer gold pieces appreciably lighter as a measure to bolster his fading finances. These two passages, as well as the coins themselves, sufficed to prove to Stefan's satisfaction that the issuance of light weight solidi went back at least as far as 565 A.D., the date of Justinian's death. In this matter of dating, however, he was not exacting enough. A closer date for the start of this series of light weight solidi can be established, if they are to be connected with the passages from the Anecdota. Certainly the fact that all of the light weight solidi are of the full-face portraiture is a clear indication of a terminus post quern of 539 A.D., the twelfth year of the reign of Justinian, which the dated bronzes indicate as the start of that style of portraiture. But even greater accuracy is possible. Had Stefan been more careful he would have noted that one of the passages from Procopius connects the monetary change with the period during which Peter Barsymes was in office as Comes Sacrarum Largitionum after he had recovered the favor of the Emperor Justinian, and that as a result the first issue must have occurred at some time between 547 A.D. and June 1, 555 A.D. 40

The detailed explanation for the existence of these solidi proposed by Stefan was a simple one. The emperors of the sixth and early seventh centuries paid large sums of money to the Avars to secure peace.41 Stefan believed that the fact that the majority of the light weight solidi found in the Balkans, Hungary and South Russia might be seen to have been struck during the reigns of Heraclius and his successor added strength to his general thesis that this light weight coinage formed a part of the enormous tribute payments to the Avars. The emperors, he contended, had mixed the light weight coins in a given percentage with the solidi of full weight in these payments. He also pointed out as further proof of his hypothesis that the eastern series of coins which he had constructed came to an end during the reign of Constantine IV Pogonatus. Thus they covered almost exactly the period during which large scale tribute payments were made to the Avars. This coincidence of the period of issue of light weight solidi with the time of the tribute payments to the barbarians of the Hungarian plain, he maintained, confirmed his hypothesis that the light weight solidi were mixed with the mass of good coinage which was used for these subsidies, and they were thus passed along to the barbarians with a resultant saving for the Byzantine government. As an instance that the practice of issuing poorer currency with better coinage was not unknown to Roman governments of an even earlier period, he cited the so-called nummi subaerati. These nummi subaerati are sometimes found to be as much as two-thirds of the total content of hoards of an earlier period, and Stefan believed that they were issued by the Roman government in an attempt to avoid the economic consequences which would have resulted from a general depreciation of the currency.42

Stefan concluded his argument by pointing out that the western finds of these light weight solidi were largely resticted to the coins of Heraclius and his son Heraclius Constantine. The hoards of France and Italy supposedly showed only these coins. The reason, according to Stefan, was a simple one. These coins arrived in the West via the commercial transactions of the western peoples with the Avars through the Lombards. It was therefore not surprising to Stefan that the hoard of Hoischhügel showed none of the coins of the eastern series which he had collected but only a single piece of what he had denominated as the western type. The coins of the western type were clearly in circulation among the Lombards prior to the inauguration of their own coinage. The light weight solidi had supposedly travelled through the channels of commerce from southern France into Italy as shown by the Lombard graves at Udine and Cividale. Coin no. 2 of the Catalogue of this monograph was found in a Lombard grave at Udine, and Coin no. 74 was found in still another Lombard grave at Cividale.

The basic argument put forth by Stefan has now been traced in some detail through the chain of reasoning set forth by that author. His was really the first serious attempt at understanding the significance of these solidi in connection with the history of the period during which they were issued. There are, however, several weak spots in the chain, and some serious reservations must be made with regard to this thesis. Several of these weak links have been indicated in the course of the exposition of Stefan's thesis, but a more complete critique is certainly warranted by the fact that Stefan's article is so often cited. The stylistic differences which Stefan speaks about in distinguishing the eastern from the western solidi are by no means as obvious and certain in the case of light weight solidi as he seems to indicate.43 The western series erected by Stefan is largely composed of solidi which can be shown to be of barbaric origin. That some of the light weight solidi were struck in the West and others in the East is clear enough in itself from a stylistic examination of the coins themselves, but unfortunately the division of these coins into these two groups is not exactly that which Stefan proposes. The inclusion of the barbaric pieces in the western series without any clear distinction necessitates a complete restudy of this aspect of the problem. The barbaric quality of most of the pieces in Stefan's classification willbe demonstrated in the next chapter.

It is in connection with the treatment accorded to the hoards and finds, however, that the most serious doubts must be retained, and this is the main prop for Stefan's hypothesis. He speaks of hoards containing such light weight solidi from Hungary, southern France and Italy. Unfortunately he cites no evidence to substantiate this claim for the existence of hoards of authentic light weight Byzantine solidi in those places, nor can they be found listed in the hoard catalogue compiled by Mosser.44 In southern France no trace of them can be found in the secondary literature, while in Italy only the two coins from the Lombard nécropoles of Udine and Cividale are noted. The crux of the situation, however, lies in Hungary, and in this case two recent studies of the finds of that region give a clear account of the picture. L. Huszár has prepared a study of the finds from the middle Danube region, and D. Csallány reviewed the evidence of the coin finds for a survey of the circulation of Byzantine currency among the Avars.45 Only a single light weight solidus of these series noted by Stefan dating from the reigns of Heraclius and Heraclius Constantine, that from Szentes, is reported to have been found in the area. The existence of coins of this type in the Budapest Museum cannot be taken as overly significant in view of this fact and the extreme mobility of these little bits of metal in the hands of coin dealers. It is a fact well attested by the number of hoards and finds recorded by Csallány that the great period of influx of Byzantine coins into the Avar kingdom was just the same as the time span covered by the light weight solidi issues, i.e., from the reign of Justinian through that of Constantine IV Pogonatus. In the eighth and ninth centuries Byzantine currency is not found in any appreciable quantity within the borders of the Avar kingdom. The high point of the penetration or introduction of Byzantine coins into that area was attained during the reigns of Heraclius and Heraclius Constantine. The defeat of the Avaro-Slavonic army before Constantinople in 626 A.D., however, really weakened the Avar kingdom, and its importance declined steadily until its final extinction by the Carolingians.

That Byzantine coins continued to enter the region in some numbers as late as the reign of Constantine IV Pogonatus (668–685 A.D.) and ceased to do so afterwards is a surprising fact for which no completely satisfactory explanation has yet been proposed. Still this coincidence in time between the introduction of Byzantine coins into the Hungarian plain and the striking of light weight solidi cannot be used to indicate that the light weight solidi were part of the tribute payments. The virtual absence of such light weight solidi from that region militates most strongly against such a hypothesis particularly when one remembers that the concentration of Byzantine coins entering the entire central and western half of the European continent fell off rather sharply at approximately the same time.

Still another point must be made in connection with this basic feature of Stefan's hypothesis. If the premise is accepted that these coins were used as a part of the tribute payments to the Avars, but their absence from sites on the Hungarian plain is to be accounted for by the fact that they circulated freely in trade, then there can be no doubt that numbers of them would be found in the region of Thessa-lonica and other Byzantine emporia which were involved in the Avar and Slavonic trade of the middle Danubian basin. The Avars must have made a great number, if not almost all, of their foreign purchases from Roman traders in exactly the same way that other barbarians did.46 If these things were true, however, the Avars would have very quickly become aware of the fraud that had been practiced upon them. The Roman merchants could only have accepted this clearly marked light weight gold at a discount. There is clear evidence indicating that the use of such light weight solidi was proscribed within the boundaries of the Byzantine Empire, and the passages leading to such a conclusion with respect to the light weight gold coinage of Gaul have already been cited in connection with the work done by Monneret De Villard. The hoards and finds support that conclusion, as will be shown in chapter three. It can hardly be seriously maintained that the Romans issued light weight solidi which were clearly marked and sent them to the Avar khan as part of their subsidy agreement, but that the use of a part of the coinage so dispatched and clearly marked at the mint was proscribed within the borders of the Byzantine Empire. How can one use such a theory to explain the chain of finds extending all along the northern boundary areas of the empire? Any interpretation of these light weight solidi must serve to explain them within the general framework of history. On this last point the theory proposed by Stefan is not satisfying. The first of these light weight solidi were issued in the reign of Justinian, probably within the period 547–555 A.D. A glance at the Catalogue will reveal that a respectable number of such light weight solidi and barbaric imitations of them were struck during the reign of Justinian. The Avars, however, can only be said to have achieved real prominence after the death of Justinian. The most important period of tribute payments to the Avars was the latter half of the sixth century and the first quarter of the seventh century. The initiation of the light weight solidi cannot have been directly connected with the payments to the Slavs and Avars which largely follow the death of Justinian. For all these reasons, which might be expanded to greater length, the hypothesis put forward by Stefan must be categorically rejected.

In 1941, however, still another very ingenious suggestion was put forth by a numismatist of note. Goodacre, on the basis of his study of a unique solidus of this series containing two imperial busts (Coin no. 79), put forth the view that these light weight solidi were issued at the mint of Thessalonica so as to accord with the peculiar bronze monetary system which was used in that city during the reign of Justinian.47 The evidence concerning the meaning of the mint mark 6S, however, will be shown to yield a different conclusion. The unusal bronze denominations found at the mint of Kherson during the reign of Justinian were found to be in conformity with the normal Byzantine monetary system.48 Suggestions have been put forward for integrating the bronze denominations current at Alexandria at the same time into the imperial system.49 The coinage of Thessalonica is another instance where such agreement must exist though the coins are too rare to make this immediately evident.

The works already discussed were not treated critically in the most recent of the large studies devoted to the coinages of this period, and their effect on the historians is therefore excessive. Le Gentilhomme, in his masterful synthesis of the numismatic evidence concerning the barbarian coinages of the West, supported the hypothesis proposed by Stefan and accepted the view that at least some of these solidi were struck at Thessalonica.50 The solidi, according to Le Gentilhomme, were struck for the purpose of using them to pay the tribute money to the barbarian Avars who, when striking their own currency, imitated the light weight solidi of Heraclius and Constantine IV Pogonatus. To prove his point Le Gentilhomme referred to the discussion by Jónás of the supposed Avar currency found in Hungary.51 The supposed Avar coins, however, cannot be shown to be imitations of the light weight solidi even though the weights are far below the Byzantine limits. Where prototypes can be discerned they are clearly not the light weight pieces. In some instances the emperor is dressed in consular garb, but none of the light weight solidi show such portraiture. In the few cases in which the inscription in the reverse exergue can be deciphered it contains the inscription CONOB or a corruption of that Byzantine formula. Even the weights are not uniform, and no determination of the standard is possible. Jónás felt that a weight of approximately twenty siliquae was possible, but the evidence is very weak. It is, however, certain that the Avars, if they ever issued coins, could not have begun striking them before the third decade of the seventh century and that most of their currency is in imitation of pieces struck in the second half of the seventh century.

The excavations in Hungary, however, clearly show a higher degree of civilization among that barbarian people than had previously been assumed. The existence of the balance type of weighing mechanism among them was well attested by the excavations, and since their coins varied widely in weight they probably passed by weight. The expression "sans doute" which Le Gentilhomme used in stating that the light weight solidi were primarily used in the tribute payments is perhaps too strong in view of the evidence. Jónás article does not add materially to the solution of the problem of the light weight solidi even though it is a very significant contribution to any study of the Avars. No authentic Byzantine solidi of the light weight series were reported by Jónás.

In 1947 Leo Schindler and Gerhart Kalmann studied the light weight solidi.52 Unfortunately their work did not take into account all of the material available. They maintained that the coins marked OBXX or retrograde BOXX had a theoretical weight of twenty siliquae, those marked OB⁕+⁕ or OB+⁕ a theoretical weight of twenty-two siliquae and those marked BOГK a theoretical weight of twenty-three siliquae because the inscription was retrograde. The coins which did not bear the letters OB or BO they wisely separated from the remainder and excluded as probably barbaric imitations. The conclusion regarding twenty-carat solidi was based on the fact that such coins showed an average weight of 4.069 grammes and the theoretical weight of coins at twenty-two carats was 4.169 grammes.

In their discussion of the bronze coins from Alexandria marked ΛГ (33), however, they reverted to the problem of the light weight solidi. They pointed out that the number of nummi that equalled a follis remained constant and was indicated by a mark of value. Whether 210 folles or 180 folles were equivalent to a solidus would not have changed the relationship of the nummus to the follis. Procopius, however, tells of a change in the valuation of the solidus from 210 folles to 180 folles. Thus the number of folles which could be exchanged for a solidus was subject to an imperial decree. Since this change in the relationship between the follis and the solidus is not reflected on the follis by different marks of value, it would be logical to presume that it indicates a change in the value of the gold coins by one-seventh of their intrinsic value.

Therefore Schindler and Kalmann, on the basis of the two passages in Procopius regarding the exchange value of the solidus, arrived at the conclusion that Justinian had reduced the intrinsic value of the solidus.53 Five hundred of the older solidi would have sufficed for the striking of 583 newer ones, but the newer ones must have been given the same valuation as the older ones or the government would have derived no benefit from the change. Edict XI of the Emperor Justinian was wrongly interpreted by these two scholars as indicating that in the year 559 A.D. the Emperor used all of the means at his disposal to maintain the fiat value of his debased currency. This, of course, does not accord with the latest interpretation of that edict by West and Johnson.54 Schindler and Kalmann viewed this edict as reproaching the Egyptian officials because they evaluated gold, whether in the form of coins or bullion, solely in terms of fineness and weight. Thus the Alexandrian mint masters were diverging from the practice of the Constantinopolitan mint which in accordance with the imperial will had lessened the intrinsic value of the gold currency. The authors therefore assumed that gold was struck in Alexandria, and that the coins which resulted differed from those issued at Constantinople. It was then noted that the light weight solidi were derived from officinae nine and ten which had previously been attributed only to the mint of Constantinople. It was a difficult feat to attribute these two officinae to the Alexandrian mint, but there were no other coins which could have been attributed to that mint, and according to their interpretation of Edict XI there must have been solidi issued there. Even though the numbers of the officinae were such that the mint of Constantinople was indicated still the usual formula CONOB had been replaced by the OBXX exergual mark. It was proposed therefore that what Procopius had reported was an actual debasement of the metal carried out at the capital, but that at Alexandria pure gold coins approximately one-seventh lighter were issued. The debased solidi and the lighter solidi would be equivalent in value. Perhaps the peculiar conditions in Egypt and the fact that foreign trade required pure gold necessitated this peculiarly Egyptian solution of the imperial proposal.

The issuance of f olles marked ΛГ or thirty-three nummi, however, in place of those of M or forty nummi would seem to be an attack on the imperial monetary policy. It would at the same time be a reflection of the peculiar Egyptian solution of the problem.

This hypothesis is very ingenious but far from convincing. There is not the slightest evidence that the light weight solidi were struck in Egypt, and the fact that none of them have ever been found in that province would seem to militate against such a premise. The passages from Procopius on which a debasement of the normal twenty-four siliquae solidi is based cannot be used to support that contention. A careful scrutiny of the passages at a later stage will show that the wording supports a light weight coinage and not a debasement. Studies of the coin alloy are few and in many cases inconclusive, but they all support the belief that the normal solidi were of relatively fine gold whereas in the few instances in which the light weight solidi have been subjected to such analysis it is clear that some debasement had been determined upon. This alone, of course, would demolish the thesis put forward by Schindler and Kalmann, but to proceed a bit further, Edict XI cannot be used in the manner suggested by these two scholars. The work of West and Johnson, which has already been cited several times, seems conclusive. The interpretation supported by Schindler and Kalmann is therefore no longer tenable. Even the view that ΛГ indicated thirty-three nummi on the Alexandrian bronzes is open to suspicion in the light of the new proposed reading of three lita which may have equalled thirty-six nummi.55 The hypothesis suggested by Schindler and Kalmann must be discarded.

In 1948, however, Marcel Jungfleisch wrote an excellent article on the subject of isolated letters found on Byzantine solidi of the seventh century, and his work bears a direct relationship to that of Schindler and Kalmann though it was completely independent.56 Jungfleisch made some interesting observations that are applicable to the problem of the light weight solidi though he did not offer a complete treatment of the question. He interpreted the exergual formula CONOB as meaning "gold of the quality of Constantinople" rather than "struck at Constantinople." Then he noted that many mints of the Byzantine Empire were used for the striking of gold, and that they often did so in the names of other mints. This freed Byzantine numismatics from the rigid bonds which had largely impeded its full development. The isolated letters which are sometimes found in the field of Byzantine solidi were to be interpreted as either dates or indications of mints striking coins for other mints. As just pointed out, this novel thesis required a completely new approach to Byzantine gold currency in particular. The legend in the exergue now became purely an indication of the fineness of the alloy of the gold coins. On that basis Jungfleisch suggested a table of fineness which was based on findings utilizing the touchstone to determine the actual gold content of the solidi. In the next chapter this table of fineness will be discussed in detail, but it can be stated at this point that certain objections might be leveled against the methods used by Jungfleisch. Unfortunately no series of chemical, spectroscopie, or specific gravity analyses was given to support the table, but according to Jungfleisch himself the use of the touchstone indicated that solidi rarely attained what he considered their theoretical fineness but showed perhaps an extra half-carat, and sometimes more, of debasement. The precision of the results seem somewhat excessive in view of the technique employed, but only tests by other methods can resolve any doubts. Perhaps the peculiar code used in the exergual markings of the solidi to indicate the standard of purity was designed so that the baser coins could be used in foreign trade ? Only a long series of analyses or the chance finding of a new text could resolve the problem.

It is hardly possible at this time to evaluate the implications of the thesis propounded by Jungfleisch in all of its aspects, but it should suffice for our purposes to point out that it can hardly be considered a complete solution of the problem of the light weight solidi. It is only for the sake of completeness that the work done by Jungfleisch and Philip Grierson can be included in this chapter. These men in no way attempted a complete study of the problem. They merely sought to indicate some suggestive paths based upon their acute observations, and it will be shown in the course of this study just how astoundingly acute their observations and suggestions were.

In the course of studying the St. Martin's hoard of Frankish and Anglo-Saxon coin-ornaments, Mr. Grierson noted that the light weight system of gold coins in use in Gaul in the late sixth century represented "the victory of a traditional Germanic weight, originally based on the Roman Republican denarius, over the slightly heavier solidus which the invaders had found in use in the imperial provinces which they had occupied—but regarding the circumstances of the change and the methods by which it was carried out we are almost entirely in the dark." He further suggested that the light weight solidi were "apparently for use of the merchants trading with the Germanic world."57 These statements will be expanded upon greatly in later sections of this study because they seem to indicate particularly fruitful channels of investigation. They should, however, also be judged in the light of Mr. Grierson's latest statement regarding the light weight solidi. In the course of studying a hoard of Byzantine solidi from North Africa in which a light weight solidus occurred, Mr. Grierson stated that it was most probably some local demand within the Empire which called for the issuance of these solidi.58 Again there is not very much that can be done to evaluate the validity of such a statement which is in the nature of an obiter dictum, but it can be pointed out that it will not serve to explain the fact that of all of the light weight solidi which have been found throughout the length and breadth of Europe only twice have they been found in clearly Roman sites.

In fine, it may be stated clearly that the situation with regard to these light weight solidi is more fluid than is generally supposed. There has up to the present moment been no explanation put forward which can be shown to have a firm historical background and which can explain both the light weight of the coins and the location of the finds as well as the time period within which they are found. Absolutely no work has been done on the iconography of these coins, which indeed shows some interesting features, as well as upon the alloy of thes pieces, though Jungfleisch does indicate that he believes them to be of worse alloy than the normal Byzantine solidi. It is because of these reasons that the current work has been taken in hand. But to a historian, of course, the coins themselves can only be of interest insofar as they give us some new information concerning the period to which they refer. It may well be impossible to give an explanation of some of the numismatic aspects of the problem. The texts are not sufficiently explicit to yield absolutely certain conclusions. Rather we should attempt to use the coins as documents with which to study the world at the time of their issuance.

| 1 |

Dr. Arnold Luschin von Ebengreuth, "Der Denar der Lex Salica," Sitzungsberichte der Kaiserlichen

Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien, Phil.-hist. Klasse, CLXIII (1910), Abh. 4, pp. 34–39. See Karl August

Eckhardt, "Zur Entstehungszeit der Lex Salica," Festschrift der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen,

1951, pt. II, pp. 16–31; and Pactus Legis Salicae 7. Einführung und 80 Titel-Text (Göttingen: Musterschmidt, 1954), pp. 186–192, which is volume III in the Westgermanisches Recht

series of the neue Folge of the Germanenrechte published by the Historisches Institut des

Werralandes. Eckhardt argues very strongly for greater antiquity for the Lex Salica. Unfortunately he is rather

cavalier in his treatment of the numismatic evidence. Also see H. Brunner, Deutsche

Rechtsgeschichte (2nd edition: Leipzig, 1906), I, pp. 312–313, and Hugo Jaekel, "Die leichten Goldschillinge der mero-wingischen Zeit und das Alter der Lex Salica,’

Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte, Germ. Abt., XLIII (1922), pp. 103–216. The literature on this subject of the

date of the Salic law is very extensive, but it is rather indirectly related to the true Roman light weight solidi. The barbarian

coinages are

used to date the Germanic law codes, but these coinages are largely imitations of Roman coinage.

|

| 2 |

Ugo Monneret De Villard, "Sui Diversi valori del Soldo Bizantino,’ Rivista Italiana di

Numismatica, XXXVI (1923), pp. 33–40. This article must be used with great caution. Several of the coins which appear twice in

separate publications are listed as separate and distinct pieces. No account was taken of the condition of the coins in discussing

the

metrological aspects of the problem, and the techniques used by Monneret De Villard are susceptible to serious

errors. He did not distinguish the pieces of barbarian origin.

|

| 3 |

There is some discrepancy between the earlier and the later parts of the article in the reproduction of these marks in the

exergues of the

coins. His meaning, however, is on all occasions quite clear, and the correct forms have been used in our text.

|

| 4 |

Monneret De Villard omitted one of the coins marked OB+⁕ from his calculations because the weight of the piece was

4.50 grammes, and therefore it was within the range of true full weight solidi. He also omitted the one coin marked OB

though the weight was 3.75 grammes. See Coin no. 29 of the Catalogue. This is not a good method of procedure

because it prejudges the result by excluding unfavorable data. though the weight was 3.75 grammes. See Coin no. 29 of the Catalogue. This is not a good method of procedure

because it prejudges the result by excluding unfavorable data.

|

| 5 |

The range of 24–25 carats would therefore have been 4.55–4.74 grammes, and that from 23–24 would have been 4.36–4.55 grammes.

|

| 6 |

A. Naville, "Fragment de métrologie antique," Revue Suisse de Numismatique, XXII (1920), pp.

42–60. It must be stated that there is no unanimity concerning the weight of the Roman pound, but the consensus of scholarly

opinion seems to

favor the traditional weight of 327.45 grammes. All of the figures quoted in this discussion of Monneret De Villard

would therefore have to be adjusted to accord with this, if they were to be used in any further discussion of the problem.

Since this is not

the case, it seemed best to set forth his ideas as he wrote them and to use Naville's calculations in the description.

|

| 7 |

Monneret De Villard cites the Capitula Extravagantia as the Memoratorium (§

de caminata). It is normally cited as Merced.

|

| 8 |

Ed. Bluhme, MGH., Legum, IV, pp. 651, 655–656. All these are glosses of the same passage, Roth., 346.

|

| 9 |

MGH., Legum, IV, pp. XXIX and XXXIII.

|

| 10 |

MGH., Legum, IV, p. XXVIII.

|

| 11 |

MGH., Legum, IV, p. XXX.

|

| 12 |

MGH., Legum, IV, pp. 651ff. The glosses are reproduced there. Cf. Edicto, Regum Langobardorum,

Historia Patria Monumenta (Augusta Taurinorum, 1855), VIII, p. CX, and Bluhme, “Leges Langobardorum," Archiv der

Gesellschaft für ältere deutsche Geschichtskunde, V, p. 255.

|

| 13 |

Isidore of Seville, Etymologiarum, XVI, 24: "Siliquae id est vicesima quarta pars solidi, ab arbore,

cuius semen est, vocabulum tenens."

|

| 14 |

Cf. Brunner, Deutsche Rechtsgeschichte, I, p. 313, note 7.

|

| 15 |

Monneret De Villard, "Sui Diversi valori del Soldo Bizantino,’ Rivista Italiana di

Numismatica, XXXVI (1923), p. 38, suggests also that the miliarense or large silver coin prior to the reign of Justinian was struck at

1/84th of a pound. It would thus be a silver counterpart of the light weight solidus. Actually he is in error, for the silver

coins were not

struck at a standard of 1/84th of a Roman pound at any time during at least a two hundred year period before the reign of

Justinian, nor did Justinian himself strike such silver coins. Heavy silver coinage is noticeably absent

in the fifth century. When the quantity of silver coins issued began to rise in the first quarter of the sixth century it

seems that a heavy

coin of 1/72nd of a pound, the counterpart of a full weight solidus, was struck, but none of 1/84th of a pound were issued.

A solidus at

1/84th of a pound would actually be equivalent to 20.57 siliquae. Monneret De Villard has apparently rounded this

off to twenty-one siliquae. Twenty-one siliquae would weigh 3.9207 grammes according to Naville. A solidus of twenty siliquae

would actually

be struck at about 1/82nd of a pound while one of twenty-one siliquae would be struck at about 1/86th of a pound. See also

Theodor Mommsen, Histoire de la monnaie romaine, trans. Duc de

Blacas (Paris, 1873), III, p. 77, note 2.

|

| 16 |

He cites E. Babelon, "La Silique romaine, le sou et le denier de la loi des Francs," La Gazette

Numismatique, VI (1902), pp. 72–73, to that effect. The point is most clearly made by Luschin von

Ebengreuth, "Der Denar der Lex Salica," Sitzungsberichte der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien,

Phil.-hist. Klasse, CLXIII (1910), Abh. 4, pp. 1–89, but especially pp. 22–39, which indicates that sometime after 580 A.D. the Merovingians began to strike their solidi on a standard of 22½ siliquae and that this standard

rapidly fell to twenty-one siliquae to the solidus. Prior to 580 A.D., he maintained, the Merovingians had struck their gold

on the

Constantinian standard of twenty-four siliquae to the solidus. A further reduction in the weight of Merovingian gold coins

to twenty siliquae

probably took place in the first decade of the seventh century, but in any event, it was an accomplished fact during the reign

of Chlotar II (613–629 A.D.). The exact date of the decline to twenty siliquae to the solidus,

according to Luschin von Ebengreuth, cannot be firmly established. S. E. Rigold, "An

Imperial Coinage in Southern Gaul in the Sixth and Seventh Centuries,’ Numismatic Chronicle, Series 6, XIV (1954), pp.

93–133, discusses this pseudo-imperial gold coinage. He suggests that it was begun during the last years of the reign of Justin

II, probably about 574 A.D. His work supersedes that of Luschin von

Ebengreuth. Cf. Maurice Prou, Catalogue des monnaies françaises de la Bibliothèque

Nationale. Les Monnaies mérovingiennes (Paris, 1892), pp. XIV-XXVII, esp. pp.

XXIV-XXV. A. Duchalais, "Poids de ľaureus romain dans la Gaule," Revue numismatique, V

(1840), pp. 261–265, and Maximin Déloche, "Explication d’une formule inscrite sur plusieurs monnaies

mérovingiennes,’ Etudes de numismatiques mérovingiennes (Paris,

1890), pp. 227–235, reprinted from Revue archéologique, 2e série, XL, provided the basic

information upon which Luschin von Ebengreuth determined his dating. See note 1.

|

| 17 |

Another series marked VIII in the case of the trientes indicates that the change was clearly understood.

|

| 18 |

Nov. Maioriani, VII, 1, 14 (458 A.D.) (ed. Th. Mommsen and Paul M. Meyer, Codex Theodosianus, II, p. 171). "Praeterea nullus solidům

integri ponderis calumniosae improbationis obtentu recuset exactor, excepto eo Gallico, cuius aurum minore aestimatione taxatur)

omnia

concussionum removeatur occasio" This passage and several other similar ones have formed the subject of a great number of articles.

Adrien Blanchet, "Les ((sous Gaulois)) du Ve siècle," Le Moyen Age,

2e série, XIV (1910), pp. 45–48, suggested that the words minore aestimatione indicated gold

that was debased and not coins which were not of full weight. He therefore interpreted this passage in terms of the few debased

coins found in

the Dortmund hoard. Wilhelm Kubitschek, "Zum Goldfund von Dortmund,’ Numismatische

Zeitschrift, neue Folge III (1910), pp. 56–61, discusses the view taken by Blanchet, and he goes even

further in formulating the theory that barbarous coinages of poor quality were an increasing problem for the Romans during

the period of the

migrations, but that by the mid–sixth century the Byzantines had conceded defeat in this matter. He probably goes too far.

Maurice Prou, Les Monnaies mérovingiennes, p. XVI ; and E. Babelon, "La Silique

romain, le sou et le denier de la loi des Francs Saliens," Journal des Savants, Février 1901, p. 120, note 1, state

their belief that a lighter weight coinage is meant. See chapter II for a further discussion of this Novella.

|

| 19 |

This reference was first given by C. Du Cange, Glossarium Mediae et Infimae Latinitatis

(Paris, 1733–36), s.v. Solidus, and it has been repeated by many

authors. E. Babelon, Traité des monnaies grecques et romaines (Paris, 1901), I, pt. I, col. 540, cites it as a formula from the collection of Marculfe. Actually this

document is of Salic origin and is given in de Salis’ edition (MGH., Leges, Sectio V, p. 77) as Formula Salica Lindenbrogiana no. 16. This is equivalent to Eugène de Rozière. Receuil des Formules usitées dans

l’empire des Francs du Veau Xe siècles (Paris, 1859–71), no. 242 or in the Rockinger edition no. 19. In these later and more scholarly editions the crucial phrase,

solidos francos, is given as solidos tantos or valente solidos tante. In

the Frankfurt edition of 1631 of the Codex Legum Antiquarum of Lindenbrog and in that of Baluze which is included in

ed. J. Mansi, Amplissima Collectio Conciliorum (Paris, 1901–27), XVIIIbis, col. 536, the phrase appears as solidos francos tantos. This is not even given as

a variant in the better editions.

|

| 20 |

Gregory I, Registrum, VI, 10 (MGH., Epistolae, I, p. 389). The editors

date this letter as of Sept. 595 A.D.

|

| 21 |

Gregory I, Registrum, III, 33 (MGH., Epistolae, I, p. 191). This

letter is dated by the editors as having been written in April 593 A.D.

Monneret De Villard cites these two letters from the Migne edition in the Patrologia Latina,

LXXVII, pp. 799 and 630.

|

| 22 |

C. Th., V, 19, 4 (ed. Mommsen and Meyer,

Codex Theodosianus, I, pt. II, p. 558): "Imp. Valentinianus et Valens AA. ad Germanianum Com(item)

S(acrarum)L(argitionum). Ob metallicum canonem, in quo proprio consuetudo retinenda est, quattuordecim uncías ballucae pro

singulis libris constat inferri. Dat. VI id. Ian. Rom. Lupicinio et Ioviano conss." This is equivalent to C.

Just. XI, 7, 2 (ed. Krueger, Corpus Iuris Civilis, II, p. 430). It is a portion of

the same law to which C. Th., XII, 6, 13, setting up the standard of seventy-two solidi to the pound for bullion

payments to the Treasury, belongs. Because of this A. Soetbeer, "Beiträge zur Geschichte des Geld- und Münzwesens in

Deutschland,’ Forschungen zur deutschen Geschichte, I (1862), p. 295, said that the propria

consuetudo mentioned was the custom of the Fiscus in collections to take eighty-four solidi from the gold mine operators. Mining as

an

industry in the Roman state, however, was peculiar unto itself. The entire title XIX of Book X of the Theodosian Code

is headed De Metallis et Metallariis. A law of 365 (C. Th., X, 19, 3) places a charge of eight

scruples on those entering the mining profession voluntarily. A law of 392 (C. Th., X, 19, 12) taxes every goldminer in

Pontus and Asia seven scruples per year. Goldmining was a peculiar industry, and it is most likely that the mine operators

were using a

peculiar pound of eighty-four solidi. E. Babelon, Traité des monnaies grecques et romaines

(Paris, 1901), I, pt. I, col. 539, however, maintained that the text in question “renferme aussi implicitement la mention de la taille à 84." The text of a law of 325 A.D. in

the Theodosian Code which would indicate light weight solidi has been preserved in two separate fragments which are recorded

in both the

Theodosian and Justinian Codes, and whose order is indicated in the Theodosian recension. C. Th., XII, 7, 1; XII, 6, 2

(ed. Mommsen and Meyer, Codex

Theodosianus, I, pt. II, pp. 722–33; 713) = C. Just., X, 73, 1; X, 72, 1 (ed. Krueger,

Corpus Iuris Civilis, II, pp. 427; 426). In the later recension the important statement regarding the weighing of

solidi has been omitted. Whether or not anything intervened between the two fragments as received cannot be ascertained, but

the text as it

stands forms an intelligible whole. It is a law concerning the collection of taxes, and penalties for improper performance

in the process of

collection are attached to the latter portion of the law. The first part of the law gives the weight of the solidus as four

scruples, i.e.,