Coinage of the Americas Conference at The American Numismatic Society, New York City

— The American Numismatic Society, 1987

Two events occurred in 1873 which contributed to the produc-tion during that year of the largest number of varieties of silver coins of any year in U.S. Mint history, without regard to die breaks, recutting of dies, errors, size and position of mint marks, and the like. All varieties are discernible to the naked eye or with a low powered glass.

The first event of importance was a letter dated January 18, 1873, from A. Louden Snowden, Chief Coiner of the Philadelphia Mint, to the Honorable James Pollock, Director of the U.S. Mint.1

I desire in a formal manner to direct your attention to the 'figures' used in dating the dies for the present year.

They are so heavy, and the space between each, so small, that upon the smaller gold and silver, and upon the base coins, it is impossible to distinguish with the naked eye, whether the last figure is an eight or a three.

In our ordinary coinage, many of the pieces are not fully brought up, and upon such it is impossible to distinguish what is the last figure of this year's date.

I do not think it creditable to the institution that the coinage of the year should be issued bearing this defect in the date.

I would recommend that an entire new set of figures, avoiding the defects of those now in use, be prepared at the earliest possible day. (See fig. 1.)

This, of course, resulted in the now well-known "Open 3s and Closed 3s" of that year. No one had publicized this change prior to my research on the coinage of 1873, beginning in 1950. Beistle 2 had mentioned an 1873 half dollar without arrows, with a 3 more open than all others without arrows.

Most numismatic research is accomplished by studying the coins themselves. Based on the Snowden letter and Beistle, I undertook to find the changes, if any, in the numeral 3 on all 1873 coins.

The other event affecting the silver coinage of 1873 was the Coinage Act of 1873, approved by President Grant on February 12,3 to take effect on April 1.

That legislation changed the weight of the U.S. dimes, quarters, and half dollars to metric standards, increasing the weights slightly. The dimes were increased by .01g, the quarters by .03g, and the half dollars by .06g. Since the Act specifically designated the coins to be minted and their respective weights, the mint could not issue any silver coins after April 1, 1873, which did not conform to the Act, whether coined prior to April 1 or after. The standard silver dollar was not authorized or mentioned in the Act.

The following silver coins were minted in 1873 at the Philadelphia Mint, for general circulation, prior to April 1: the half dime, dime, quarter and half dollar without arrows, and the standard silver dollar, none of which could be issued after March 31, 1873, because they did not conform to the Act.

A precedent had been set in 1853 for a weight change in silver coins, so the Mint followed that in 1873 by placing reversed arrows pointing outward from the sides of the date on dimes, quarters, and half dollars, to show the increase in weight. But the 3 cent piece, made only in proof and prior to April 1, the half dime and standard silver dollar were not authorized or mentioned in the Act, and thus were discontinued. The trade dollar was authorized in the Act, and its coinage commenced on July 11, 1873,4 after substantial design problems.

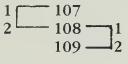

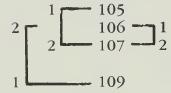

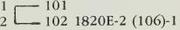

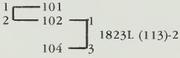

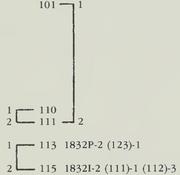

There are thus 9 different weight silver coins which were issued in 1873 for general circulation. They are: the half dime, two different dimes, quarters and half dollars, the standard silver dollar, and the trade dollar, all from the Philadelphia Mint. We also have the Open and Closed 3s in the dimes, quarters and half dollars without arrows (see fig. 2), and the half dollars with large and small arrows (see fig. 3), as well as what can be called the "4-striper" half dollar with small arrows, caused by a bounced die. All half dollars made from 1839 through 1891 have the vertical bars of Liberty's shield in groups of three. This 1873 variety is the only one that has them in groups of 4. It is unmentioned in Beistle and, thus, is my discovery (see fig. 4).5

In major varieties there are therefore 15 different business strike silver coins made at the Philadelphia Mint, as well as 10 different proof strikes of the basic coins, totaling 25 different silver coins dated 1873 from the Philadelphia Mint.

If we include the silver coins from the branch mints in 1873, there are 7 from the San Francisco Mint, and 8 from the Carson City Mint, making 40 different silver coins minted in 1873. The San Francisco Mint coins are: the half dime, the half dollar without arrows and the standard silver dollar,6 as well as the dime, quarter and half dollar with arrows, and the trade dollar. From the Carson City Mint there are the dime, quarter and half dollar without arrows7 and the standard silver dollar, as well as the dime, quarter and half dollar with arrows and the trade dollar.

There is one more variety that is often overlooked, because few people collect dimes. It is the Philadelphia dime with arrows, which comes in a high and low date, also discernible with the naked eye (see fig. 5).8 So we now have 41 major varieties, in the aggregate, of silver coins minted in 1873.

The Coinage Act of 1873 is often referred to as the "Crime of 1873 " Why was it called a "Crime," and is that justified?

The Act of 1873 had a long and devious history, going back as far as 1867. In that year an International Monetary Conference was held in Paris, and our representative was Samuel B. Ruggles, a member of the Chamber of Commerce of New York City. Senator John Sherman of Ohio, Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, con-veyed a message to Ruggles to press for a single international coinage standard—gold.

In June 1868 Senator Sherman, who also attended the conference, made a report to the United States Senate in favor of a "single coinage standard, exclusively of gold." In the same year, Sherman introduced a bill in the Senate, having the same objective: a single standard of gold.9 This bill was accompanied by letters of approbation from Secretary of the Treasury George S. Boutwell, Deputy Comptroller John Jay Knox, and various reports and recommendations from subordinate officials of the Treasury Department, including the mint. But there was nothing in any of the reports that indicated the slightest comprehension of the economic effect of demonetizing silver.

Senator Sherman introduced Senate bills in the two succeeding Congresses to effect his goal of making gold the sole standard of the United States. His bill of April 28, 1870, included "revising the laws relating to the Mints, Assay Offices, and coinage of the United States," which, of course, was referred to the Senate Finance Committee of which Sherman was Chairman. On December 19 Sherman reported the bill back to the Senate with some amendments, among which was a charge for coinage of silver brought into the mints.

The bill was adopted in committee January 9, 1871, as amended, and passed the whole Senate but with the amendment calling for a charge for coinage striken out. It is interesting to note that Sherman, who had voted for the amendment to charge for coinage in committee, voted against it when the bill reached the Senate floor on January 10 and was sent to the House the same day.

In the House of Representatives, the bill was bandied back and forth between the committee and the floor for over one year. Samuel Hooper of Massachusetts, on April 19, 1872, in a debate in support of the bill, let drop a remark in the House which helps to explain the origin of the carefully laid plot to change the money standard of the United States. He made this admission: "Mr. Ernst Seyd of London, a distinguished writer who has given great attention to the mints and coinage, after examining the first draft of this bill, has furnished many valuable suggestions, which have been incorporated in this bill" (italics added). It is not known what parts of the bill Mr. Seyd furnished. It is highly improbable that he came all the way from London to make suggestions about the basis for our coinage, the practical running of our mints or about the devices on our coins. We will hear about Mr. Seyd again.

On May 27, 1872, the same Mr. Hooper offered a substitute bill in the House, which, after much argument, was finally voted on and approved, without even having been read.10

The next day it went back to the Senate, and again was referred to committee. Senator Sherman finally called the bill up before the Senate on January 17, 1873. The Senate passed it and, since it had been amended, it went to conference and was approved by both houses on February 12, 1873. President Grant, deferring to Congress, approved it the same day, to take effect on April 1, 1873.

An undated pamphlet, "The Crime of 1873," was printed about 1895 by the American Bimetallic Union, which had offices in the Sun Building, Washington, DC, and 134 Monroe Street, Chicago.11 Near the end of the pamphlet is a copy of an affidavit, dated May 9, 1892, sworn to before the Clerk of the Colorado Supreme Court, by a prominent Colorado citizen, Frederick A. Luckenbach. In the affidavit, Mr. Luckenbach stated that he had become acquainted with Mr. Ernst Seyd of London in 1865, and had visited with him and his family on every trip Luchenbach made to England. That in February 1874, Luckenbach was visiting with Seyd, when the London papers had hints of corruption in Parliament, and he commented on it. Seyd then told Luckenbach, "If you will pledge me your honor as a gentlemen not to divulge what I am about to tell you while I live...." Given the pledge, Seyd continued, "I went to America in the winter of 1872-73, authorized to secure, if I could, passage of a bill demonetizing silver. It was in the interests of those I represented—the governors of the Bank of England—to have it done. I took with me 100,000 pounds sterling, with instructions if that was not sufficient to accomplish the object, to draw another 100,000 pounds, or as much as was necessary. I saw the committees of the House and Senate, paid the money and stayed in America until I knew the measure was safe." At that time, —100,000 sterling was equal to $500,000.

The Honorable Thomas Fitch of Nevada, at a later Silver Convention in St. Louis, said to great applause: That the nation which consumes 50% and produces but 7% of the world's supply of silver,

beguiled the nation which produces nearly 50% and consumes 25% of the world's supply of silver, into a conspiracy to strike

35% of the

value of silver. The nation which is the biggest importer of wheat in the world, inveigled the nation which is the greatest

exporter of

wheat in the world into a financial and commercial dead-fall where 35% was taken from the value of the wheat. The nation

whose

looms would be idle, and whose people would be hungry, and whose government would be upheaved upon a storm of riot without

a supply of

American cotton, deceived the nation which is the biggest producer of cotton, into striking 35% of the value of the cotton.

Why, Gentlemen,

England is the bunco steerer of the world, and Uncle Sam

is the gentleman from the rural districts.12

It is now evident who was responsible for the Crime of 1873. Some of the effects of the Coinage Act of 1873 were:

At the time the Act passed, specie payments for legal tender notes had not been resumed, and the public debt was still high from the Civil War obligations. Most U.S. Bonds were held in Europe, and it was in the interests of European investors that the U.S. debt be paid in gold.

By demonetizing silver, half of the metal in which bonds could be payable was deprived of monetary use for that purpose, and the other half had almost doubled in value. In effect, it almost doubled the public debt.

Congress debated for many years after 1873, trying to fix the blame for the Crime of 1873, and trying to nullify the effect of the Act. The Congressional Record, periodicals and newspapers were full of debates and accusations. Even most of the legislators who passed the Act were not aware of the enormous impact it had on the United States. Even President Grant, who approved the Act, was not aware of its impact.16

The passage of the Coinage Act of 1873 really was the Crime of 1873. The criminals have been identified, and some of the economic effects have been detailed.

| 1 |

Harry X Boosel, 1873-1873, (hereafter cited as Boosel) (Chicago, 1960), p. 7.

|

| 2 |

M.L. Beistle, A Register of Half Dollar Die Varieties (Shippensburg, PA, 1929), p. 175,

no. 1873 4 A.

|

| 3 |

Annual Report of the Director of the Mint for 1873, pp. 25-33, provides the full text of the Coinage Act of 1873.

|

| 4 |

Boosel, p. 39.

|

| 5 |

Boosel, p. 24, illustrates the discovery coin of this variety.

|

| 6 |

Although the 1873 San Francisco half dollar without arrows and the 1873 standard

silver dollar are unknown in any collection, Boosel, p. 41, cites proof that they were minted.

|

| 7 |

There is a unique dime known of Carson City for 1873, and only three quarters without arrows from Carson City. Boosel, p.

45, proves coinage of 12,400 dimes without arrows for 1873, and

4,000 quarters without arrows,

|

| 8 |

Boosel, p. 20, illustrates the discovery coins of this variety.

|

| 9 |

S. 217, 40th Congress.

|

| 10 |

H.R. 1427, 42nd Congress, 2nd session. Hooper's substitute bill is H.R. 2934.

|

| 11 |

Monograph No. 28, reprinted with extensive revision from Silver in the Fifty-First Congress.

|

| 12 |

The National Silver Convention was held in St. Louis on November 26, 1889, and there were 250 delegates from 28

states in attendance.

|

| 13 |

R.S. Yeoman, Guide Book of United States Coins (Racine, WI, 1987), pp. 185, 189-90. The first gold coin struck for the United

States was the half eagle ($5) of 1795—weight 8.75g, .9167 fine; changed in 1834 to 8.36g, .8992 fine; changed in 1839 to

8.359g,

.900 fine.

|

| 14 |

John M. Willem, Jr., The United States Trade Dollar (New York City, 1959), p. 113.

|

| 15 |

Willem (above, n. 14), p. 113. The bill was received by President Cleveland on February

19, 1887, but was not signed by him. The bill became law on March 3, 1887.

|

| 16 |

McPherson's Handbook of Politics for 1874, pp. 134-35. It is doubtful whether Grant could have even read and

understood the 67 sections of the Act in the one day that he took to sign the bill into law.

|

Coinage of the Americas Conference at The American Numismatic Society, New York City

© The American Numismatic Society, 1987

The Industrial Revolution in the United States prior to the Civil War created the need for more coins. As a result, there was a cor-responding need for a faster and more efficient method of making dies.

Primarily, three improvements at the U.S. Mint allowed more dies to be made in less time. These improvements were better materials, so that dies could withstand greater pressure without breaking, steam power to operate the presses, and the purchase of a transfer lathe.

This article is devoted in the main to the transfer lathe, probably the most important improvement in the production of dies.

Fig. 1 illustrates the type of transfer lathe purchased by the mint in 1836 in order to produce a punch for the main design.

In his major work entitled The U.S. Mint and Coinage

1

Taxay described how the transfer lathe operated, as follows: The portrait lathe operated on the principle of a

three-dimensional pantograph. A long, rigid bar or lever, ran along the front of the lathe and hinged, at the farthest left-hand

side, to a

fulcrum. At a short distance from the fulcrum a very sharp graver, or cutting tool, was fastened to the lever.The graver faced

a soft

tool-steel cylinder (the hub blank) which was fixed on a large, solid wheel. Toward the right end of the lever, a

pointed steel stub was mounted directly opposite the casting.

By means of a spring at the upper end, the lever was drawn in, causing the graver and the tracing point to touch the center

of their

respective models. The models were now rotated in an equal counter-clockwise motion, with the two points gradually working

their way to the

edge. In this duet, the tracing point was the leader, and its motions were precisely reproduced on the hub in a smaller ratio,

the proportion

being established by the distance between the two tools. After every complete revolution, a screw mechanism lowered the right

end of the lever

slightly, placing the two tools closer to the edge of their respective models. The entire operation was repeated several times

until the

design was sufficiently blocked out. Even then, however, it was comparatively rough and required a good deal of hand finishing

before the

master hub could be used to sink a master die.

The transfer lathe had certain limitations and could only be used to make a main design punch and other individual punches. The cutting of one positive punch containing all of the parts of the die had to wait until 1907 when the mint acquired the Janvier transfer lathe.

We know that in 1836, the mint had the capability of making a main design punch. We also know that the mint did not yet have the capability of making one die by the use of a transfer lathe. Thus, the question of how master dies and master hubs were made arises.

The numismatic literature available does not describe this process in detail, and therefore we must look to the numismatic evidence itself to arrive at a narrative account of how master dies and master hubs were made from 1836 to the end of the century.

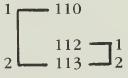

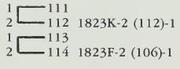

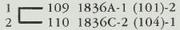

An overall view of this process is shown in fig. 2. There are three pieces of evidence I used in making my determinations: a Gobrecht die in the Smithsonian Institution collection; three die punch trial pieces in the American Numismatic Society collection; and the 1857 die punch trial piece reported in Judd.2

In 1985, I had the privilege of viewing the SI collection, where I found an obverse Gobrecht die which appeared to be severely worn. It did not bear Gobrecht's name and appeared to be a very early brass die (fig. 3).

When I first saw this die, I thought it had been defaced so that it could no longer be used. I have now come to a different conclusion. I believe that the die had been lightly scored, giving it a checkerboard effect, so that additional items, such as stars or Gobrecht's name, could be added. It is interesting to note that the letters "C. Gobrecht F" were punched five separate places on the reverse of this die, almost as if the punch was tested first and it was later decided not to use the punch on the die because the die was worn out (see fig. 4 and punch enlargement). I therefore assume that a new die was made and this one was formally retired. I also suspect that Gobrecht's name was added to this master die with one punch rather than individual letters. It was most likely that Gobrecht's name was to be added to this master die, and the checkerboard effect was to be polished off once the name was added.

At the ANS, I found three die punch trial pieces, the first of which (fig. 5) is a die punch trial piece showing the main design of one of the standard silver obverse patterns of 1869. After the transfer lathe produced the master design punch (a puncheon), having the size for the denomination required, this punch was struck onto a copper planchet.

After the main design was punched onto the copper planchet, a horizontal and a vertical line were drawn through the design. Thereafter, as shown in fig. 6, a compass was used to draw two circles around the design so that the legend letters could be applied. After the circles were drawn, individual punches were applied with the letters "UNITED STATES OF AMERICA" within the circles.

In fig. 6, the mint worker experimenting with the lettering made a mistake in his spacing. The last "A" in "AMERICA" was not punched in because, if applied, it would have fallen below the horizontal line, creating an obvious imbalance.

He then started over, this time starting slightly higher and placing the letters a little closer together, as exhibited in fig. 7. It also appears that he experimented with the date punch.

He then started over, this time starting slightly higher and placing the letters a little closer together, as exhibited in fig. 7. It also appears that he experimented with the date punch.

Once the designer found where the motto and design should be placed on the copper piece, the same process, using the same punches, was applied to the master die. When the punches were properly applied, the horizontal and vertical lines were polished off the master die, which in turn was used to make a master hub or working hubs, and, ultimately, working dies.

The denticles were added to the master die by drawing two circles around the perimeter of the die. Within these two circles, a two-denticle punch was applied. Each additional denticle was added by placing the first leg of the two-denticle punch into the previous slot, and was punched again, adding one additional denticle at a time, creating the proper interval. This process accounts for why the den-ticles vary from design to design.

The 1857 die punch trial piece reported in Judd-Kosoff is reproduced as fig. 8. This piece clearly shows that the Mint was able to make letters and numbers of the same style, but in various sizes. I believe that the transfer lathe was used to produce individual letters of the size needed for each denomination, as well as for making a single, straight-line punch of letters or numerals. Evidently, only a date or name in a straight line could be made in one punch. Punches that would work in a circle or arc could not be made with a transfer lathe. This awaited the Janvier machine in 1907.

A date logotype is a number punch with two or more digits on the punch. I believe that by 1857 the U.S. Mint was using a fourdigit logotype. The transfer lathe was used to make number pun- ches by approximately 1847, based upon my close inspection of Liberty Seated material of this era. Prior to 1847, the numbers ap-pearing on Liberty Seated coinage were very crude, as if they were made by hand. A comparison of the digits on 1846 and 1847 coins indicates that those on 1847 coins are much crisper and clearer, leading me to conclude that the transfer lathe was used to make individual digits at this date.

Taxay has argued that a two-digit logotype was used on large cents and half dollars in 1840, and a three-digit logotype was used on smaller coins.3

Walter Breen claims that a four-digit logotype was used on smaller coins as early as 1840.4 He further claims that the adoption of the four-digit logotypes may have been difficult for large denominations.

It is clear that by 1859 the mint was using four-digit logotypes, as shown by this punch for the 1859 dollar in the SI (fig. 9). I submit that a transfer lathe was used to create four-digit logotype punches for all denominations when the mint was revamped in 1857.

A close look at the numbers on the 1851 and 1852 dollars will reveal that the last digit is always lower than the other numbers. It is well-known that the dates were individually added to the work-ing dies each year. From inspection of the last digits on numerous seated dollars and other denominations of the Liberty Seated series, I have come to the conclusion that by 1857, the last digits were made by a mechanical process and the styles of the numbers from denomination to denomination were always the same–only the size of the numbers changed.

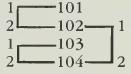

Fig. 10 illustrates the last digit of each date from 1840 to 1873. If the three styles of numbers do not match those of your coins for any particular date, the numbers have probably been altered in some way.

| 1 | |

| 2 |

J. Hewitt Judd, United States Pattern, Experimental and Trial Pieces, 7th ed., A. Kosoff, ed. (Racine, WI, 1959), p. 232.

|

| 3 |

Taxay (above, n. 1), p. 152.

|

| 4 |

Walter Breen, Dies and Coinage (New York City, 1962),

p. 16.

|

Coinage of the Americas Conference at the American Numismatic Society, New York City

— The American Numismatic Society, 1987

The collecting of half dimes by die variety can easily be traced back more than one hundred years. Harold P. Newlin, writing in 1883, opened with the admonition, "it seems unjust that these small but interesting coins should be so slighted, especially when the larger members of the family, the dollars, halves, quarters and cents, are treated with such distinguished attention, and so many articles written descriptive of their beauty."1 Newlin continued with the reason some of us collect such coins: "an 'amiable face,' the length of a curl, in short, in a coin any marked peculiarity sui generis seems to insure for it a greater appreciation and value, and one experiences no small feeling of pride in being the happy possessor of a unique piece."

I cannot speak for everyone who has had such a thrill, but I know that, in my case, discovering a new variety is a grand and a glorious feeling. And when other specimens of that variety are eventually found, it matters not, because only one person can be first.

Newlin listed 25 different varieties from 1792 through 1805. For the Capped Bust design, used from 1829 to 1837, he very briefly mentions, "...two varieties of 1835, viz: large and small date, the latter being the scarcer."2 In the Seated Liberty series he mentions two varieties of 1840, with and without drapery, and states, "there are two varieties of the 1848 half-dime, large and small date."3

Another feature of the Newlin work was the enumeration of 16 examples of the classic rarity, the 1802 half dime. A little research on the 1802 highlights some of the present collecting activities that get so much publicity. In 1935 a coin dealer named Macallister stated he knew of at least 35 different pieces. In the 1960s and 70s, 1802s appeared infrequently and three or four years might pass between auction appearances. The Mid-American Rare Coin Auctions (San Diego Sale), Sept. 28-29, 1984, 276, listed an 1802 half dime Extremely Fine (45/45), Valentine-1, which sold for $55,000 with the buyer's fee. The description stated, "No examples appeared in 1976, 1977, 1980, 1981, 1982 (to our knowledge), 1983, or yet this year," and, unfortunately for scholars, this condition census piece was without pedigree. The piece reappeared in July of this year (Auction '86, July 25-26, 1986, 1041), where it was listed as Extremely Fine-40 and sold for $41,250 with the buyer's fee. This same sale also included the Garrett 1802 half dime, lot 78 V.1 (R-5) Choice Extremely Fine-45, ex Bowers & Ruddy Galleries (Garrett Coll. Part 1), Nov. 28-29, 1979, 234. With the buyer's fee included, it realized $40,700, as compared to the $45,000 it realized in 1979.

Is this today's market reality? Changing grading standards? Prices for true rarities are still less than during the boom years of the late 1970s. Where are the collectors? I do not have the answers, but I think it is of value to make these observations.

In August 1927, Will W. Neil took up where Newlin left off by publishing a list of "The United States Half Dimes From 1829 Through 1873".4 Included were 53 varieties of the Capped Bust design and 137 varieties of the Seated Liberty design. In an adden-dum published in December, he listed 11 additional varieties.5 The problem with the Neil list was that he gave numbers to different die states of the same marriage and included the notorious 1833 "oversize" half dime. I don't believe he actually saw this piece and only used the information published in the November 1927 issue of The Numismatist.6 The piece was illustrated and the owner, F.D. Langenheim of Philadelphia, reported the diameter as 17.5 mm and the weight as being half way between a regular issue half dime and a dime. The actual weight was not given. What is believed to be this coin reappeared in 1979 in a Milwaukee coin shop "junk box." It was purchased by Jim Skwarek, who attributed it as a Valentine-5, and told me the coin weighs 19.4 grains—just about right for a worn half dime. My best guess is that the coin was probably hammered out between two pieces of leather. The story was reported in the May 1986 issue of the John Reich Journal.7

In 1931 the American Numismatic Society published Valentine's The United States Half Dimes.8 This was a significant improvement over previous publications and included photographs of most varieties, enlarged to two diameters. Valentine had expanded the list to 29 varieties from 1794-1805, 69 varieties of the Capped Bust design and an uncounted number of Seated Liberty varieties.

In 1958 Walter Breen published on half dimes in what was the final issue of The Coin Collectors Journal, No. 160, as reborn under the auspices of Wayte Raymond Publications. Breen did a lot more than add new varieties. He commented on emission order, listed some of the finest known specimens and added rarity ratings to the significant marriages.

By 1974 the Valentine book was becoming harder to find and Quarterman Publications announced their plans to reprint it, along with the Newlin, Neil and Breen monographs. Kamal M. Ahwash and I also added some new varieties, a few observations and a price guide. This book is easily obtainable and has pictures of almost all the varieties.10

Today's collector also needs Jules Reiver's "Rapid Finder" guide to half dimes, published in 1984.11 In addition to presenting his method of identifying marriages, he included six new discoveries, gave rarity ratings for all of the varieties and published the first plates of the new 1835 B-ll reverse and the new 1837 reverse used to strike M-4 and D-5. Reiver broke with what had become the tradition for varieties discovered after Valentine. He labeled all of his marriages with a V. Breen, Witham, I and others had continued the numbering of varieties by taking the next number for that year and, in place of the V, we used the first initial of our surname to identify the discoverer. The system had worked well, until John Marker came up with 1830 J-12. We were using M to designate the 1829 M-16 and 1837 M-4 discovered by John McCloskey. Using all Vs was one way to avoid a decision about what to call the 1830 V-13.

The rediscovered 1801 Valentine-2 is a good example of some of the problems encountered with the Valentine book. Until Dr. Eric Gutscher bought Stack's, June 18, 1986, 761, 1801 half dime V.2 (R-5), no one seemed to be sure what Valentine-2 looked like. Is this the variety Valentine saw or a new discovery? Jules Reiver and, apparently, quite a few other people have been labeling the late die state V-l as a V-2. Even Stack's is inconsistent. Neither of the two 1801 Valentine-2s listed as lots 76 and 77 in Auction '86 match this piece. The obverse is easily identified by examining the spacing of the stars on the left side. The position of S5 to the upper ribbon end can be used in checking catalogue illustrations. This variety may be a true rarity.

The story of 1829 M-16 goes back to before the 1975 Valentine reprint. When doing my research, one of the things I did was to take copious notes on the Stewart P. Witham collection. Witham had the most complete variety collection known to me. He had 73 of the then known 75 Capped Bust varieties. The condition of his coins was superb; almost all of them were uncirculated or proof. The only other collector I know who tried to assemble an uncir-culated set was Carl McClurg. He had 56 different varieties before he lost interest and sold his set.

The two varieties Witham lacked were 1829 V-10 and 1832 V-4. He asked me to help find the two missing marriages. I found my first Valentine-10 about one month later. Unfortunately, it had a hole in it. The coin was a nice F/VF, so I bought it and gave it to Witham. I found two more within a year and he ended up with an EF piece. I had told several other collectors about the key attributes and, in 1975, John McCloskey found an 1829 with the Valentine Reverse-10, but the obverse didn't match the Valentine-4 description. He bought the coin, later identified the obverse as Valentine-1, and the coin is now recognized as 1829 M-16. Before I could find my first 1832 Valentine-4, Witham sold his collection to RARCOA and it was auctioned off at the Milwaukee Central States Numismatic Society Show, April 30-May 1, 1977. Oddly enough, I found my first 1832 Valentine-4 in October of that year.

John Marker of Ohio collected nickel three cent pieces because he liked coins with die cracks. As some of you probably know, Capped Bust half dimes are a rich field for cracks and cuds, and, after Marker ran out of nickel three cent varieties to collect, he started collecting half dimes about 1980. He found 1830 J-12 shortly thereafter. It is a marriage of 1830 Obverse-2 and the reverse of 1829 V-10. This reverse was also used to strike the 1831 Valentine-7. But it is not the workhorse that one might initially think. The 1829 and 1830 strikings must have been limited as all of these marriages are quite rare. Reiver lists them as R-7 (4-12 known). I would only disagree on the 1829 V-10. I have seen five of them and would be more inclined to call it an R-6, at best.

The 1830 V-13, a new marriage of Obverse-9 and Reverse-3, was discovered by a dealer, who shall remain nameless. He wasn't sure of his attribution and sent it to Eric Gutscher at a certain price. Gutscher called me and when we had confirmed what it was, he notified the dealer. The dealer then raised the price of the coin. Gutscher then refused to buy it and sent the coin to Jules Reiver, who now has it in his collection. I remain disturbed by the dealer's actions since I do not think this is the way to conduct a business.

1833 L-9, a marriage of Obverse-7 and Reverse-5 of 1832, doesn't have much of a story. It was found a few years ago by Russell Logan at a small Cleveland coin show.

The new varieties of 1837, M-4 and D-5, are parts of one story. M-4, discovered by John McCloskey, is a marriage of Obverse 1 and a new reverse. It is a lot easier to identify than to find. Interestingly enough, it has a recut or repunched C in AMERICA, similar to the 1829 V-10 reverse. I find the most distinguishing feature to be the flag of the 5 in the denomination. It is completely under the feather. After McCloskey described it to me, he noted, "it is the only half dime like that." In checking my collection, it appeared that he was right. Later, when looking through some duplicates, I did find one 1837 with the new reverse. Only my VF-20 coin had 1837 Obverse-2 and D-5 became one more marriage for which to look. I took the coin to the 1975 Los Angeles ANA convention, where I showed it to Stewart Witham at lunch and, when we got up to leave, I inadvertently left it on the table. I soon discovered my mistake, but no one in the restaurant could remember seeing it. I don't know if the coin ended up in the trash or the pocket of a not so honest employee.

In all, there are five or six collectors who have shared the excitement in recent years of finding at least six, and possibly seven, new marriages. Within the John Reich Collectors Society, there are about 100 collectors who have indicated an interest in half dimes, but I don't know how serious they are about trying for all of the marriages, no matter what the series. For the Capped Bust series, "87 Different" doesn't sound like an impossible goal.

| 1 |

A Classification of the Early Half Dimes of the United States (Philadelphia, 1883), p. 3.

|

| 2 |

Newlin (above, n.l), p. 14.

|

| 3 |

Newlin (above, n.l), p. 15.

|

| 4 |

The Numismatist 1927, pp. 456-65.

|

| 5 |

Will W. Neil, "Addenda to List of United States Half Dimes," The Numismatist 1927, pp.

744-45.

|

| 6 |

"An 'Oversize' Half Dime of 1833," The Numismatist 1927, p. 690.

|

| 7 |

James Skwarek. "Rediscovery of the 'Oversize' Half Dime of 1833," John Reich Journal,

Vol. 1, 2 (1986), pp. 16-17.

|

| 8 |

D.W. Valentine, The United States Half Dimes, ANSNNM 48 (New York

City, 1931).

|

| 9 |

Walter Breen, United States Half Dimes: A Supplement (Montauk, NY, 1958).

|

| 10 |

Daniel W. Valentine, The United States Half Dimes (Lawrence,

MA, 1975).

|

| 11 |

Julius Reiver, Variety Identification Manual for United States Half Dimes 1794-1837 (Wilmington, DE, 1984).

|

Coinage of the Americas Conference at The American Numismatic Society, New York

— The American Numismatic Society, 1987

My 1980 book on early U.S. coinage provides the introduction to the die group theory of coinage.1 Application of this theory permits the determination of the sequence of die origin and the subsequent production sequence.

Chapter 2 is an analysis of the half dollars of 1794 and 1795 and what I term Group Strength. This article develops more fully the reasoning behind this approach to organizing the coinage and to understanding early minting practices.

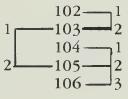

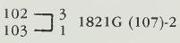

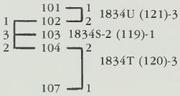

Figure 1

THE TWELVE FLOWING HAIR HALF DOLLAR DIE CHAINS

The various combinations of 25 obverse and 26 known Flowing Hair reverse dies used for the production of the Flowing Hair design half dollar are formed from 12 die chains fig (see fig. 1). You can build one of these die chain sequences by simply purchasing the Overton or Beistle half dollar books.2 The only change is in the — chain; the left hand die is a new obverse, which I discovered in 1976. It is an unusual obverse, bearing all the traits of the 1795 small head Flowing Hair half dollar. For many years these Flowing Hair half dollars of 1795 have been attributed to John Smith Gardner, assistant to Chief Engraver Robert Scot. Hired on November 19, 1794, Gardner would have been responsible for this one 1794 half dollar obverse die.

Since there were six obverse dies dated 1794 and the only delivery of half dollars occurred very late in the year on December 1, 1794, the entire group of six sets of dies must have been prepared prior to the commencement of the half dollar coinage.3 On this basis, I reasoned that they were using a number of sets of dies rather than just a single set. Since a few days were required to manufacture each die in the engraving department, it appears logical that the Mint Director would have wanted multiple sets of dies on hand. If only a single set were available and a die deteriorated beyond use, the entire output of the mint would have halted until a new die could be made. Such a procedure would have been unlikely in an establishment under the control of David Rittenhouse, a man who had the reputation of being the greatest scientific mind in the United States in his day.

Since there were six obverse dies, the assumption was that the mint used six sets of dies for the half dollars. The total number of Flowing Hair half dollar dies (25 obverse, 26 reverse) indicates that at least five groups of dies were made, that is, four complete sets of six dies with one left over. Therefore, the necessary groups of dies would have been rebuilt at least five times. The 12 chains can logically be ordered into 5 groups as diagramed in fig. 2. The 1794 chains, which I have labeled a and —, form Group 1.

An examination of all the dies confirmed the theory that there were indeed six obverses and six reverses. There are in the entire series six reverse dies with a Type 1 eagle hub. The shape of the eagle on the coin reveals that two hubs were used in the entire 1794 and 1795 series. The Type 1 hub appears only six times; five of those are in the 1794 series and the E die that was carried over and the sixth is the F die. On the basis of the eagle hubs, the die chain was placed in the next group. An examination of the rest of the dies shows that there were two types of wreaths used on the 1794 and 1795 dies. The Type 1 wreath of 1794 and early 1795 has fewer leaves than the Type 2 wreath, which occurs on only a few of the late 1795 reverse dies. All the Type 2 wreaths appear in Group V, which comprises six obverses and five reverses; an indication that there would have— been one reverse left over, which I term the hex die. The analysis of the Type 1 and Type 2 eagle hubs therefore yields the chains labeled a, —, and d at the left on fig. 2, as well as f, — and ?, the last three chains completely to the right.

An examination of the edges of the half dollars was then necessary. The use of two edge designs was confirmed. All of the 1794 half dollars and the early 1795 halves have an edge design which has two stars after the words FIFTY and DOLLAR. Presumably, the die which initially made the edge design on the coins broke and was replaced with another edge design with three stars beside each of these words. In both cases, the number of stars on the edge of the half dollar is 15; only their location changed. Careful examination of the edge designs distinguishes coins of one die pair, identified as 14-N, which have both the old and new edge design, although the old edge design predominates. An additional 170 coins with both the old and new edge design, among which the vast majority bears the new edge design, have been analyzed. These latter coins are labeled 17—0. In other words, the planchets were apparently prepared in advance and, consequently, when the coins were struck, there was a mixed box of planchets with both the 14-N and 17-0 edge die. These two chains are labeled ? and ? in the sequence. This sequence is borne out by examination of the other die varieties. All coins prior to 14-N have the Type 1 edge design and all of the coins after 17—0 have the new edge design. The location of the coins can thus be determined exactly.

Fig. 2 illustrates an initial six sets of dies—obverses 1—6 and reverses A-F. The mint started striking coins with 1-A. The A die broke, and was replaced by B with obverse 1. Both dies then broke. Striking continued with 2-C in the press until 2 broke and was substituted by 3-C. When the C die broke, D was used. This procedure continued until 6-E, when the sixth obverse die broke. All the dies were thus used. E is a used survivor and the F die was never used. Consequently, six sets of dies had to be rebuilt before more coins could be struck. In this case, since it was already into 1795, six more obverses were needed, and, since there were two survivor dies, four more reverses were engraved. With the next set of dies, Group II, the mint recommenced striking coins. When the second chain of coinage was completed, one reverse survived, the J die. Again six obverses and five reverses were made and the striking of Group III coins was begun.

At the end of this series, either one of two events took place as the 18-O combination was being struck. Either the 18 and the O dies were in the press when the rebuilding of the six sets commenced, which did not include either of these dies; or the O die, which had become clashed, was not counted as a viable die. As a result, when the group was rebuilt, four obverses and six reverses were made to begin the next sequence of striking. At the end of Group IV, three obverses remained. This is proof that this sequence is correct. Since three obverses survived, three obverses and six reverses would have been made in order to rebuild the number of dies to six sets. In fact, the obverses, labeled 23, 24 and 25, made to rebuild this die set, are all now the small head variety of 1795, which has been attributed to John Smith Gardner. The assistant engraver made all the obverse and reverse replacements to complete the Group V die set. Since three obverses survived, he had to make only three small head obverses. The entire set of six reverses, which are all of the Type 2 wreath design, were also engraved.

Figure 2

12 FLOWING HAIR HALF DOLLAR CHAINS ARRANGED INTO 5 GROUPS

This theory is significant, because not only can the die sequence be determined, but also some contemporary history of the mint can be ascertained. The mint was not relying on one set of dies at a time. A group of dies was kept in stock and periodically replenished. Another good example of this procedure is the 1794 half dime. Even though there were three obverse 1794 half dime dies, no half dimes were struck in 1794. This is eloquent testimony that three sets of dies were on hand for the half dime series.

I am also interested in the survival rate of these coins as a means to determine the approximate numbers of each variety extant. Toward this end, in 1954 I began a survey of all 1794 half dollar specimens by die variety. Over the years I have recorded every 1794 half dollar example I have seen. When I had recorded approximately 75 1794 half dollars, I observed that whenever I saw a 1794 half dollar, chances were about one in four that I had already seen it. In the range of 90 to 110 distinct 1794 half dollar specimens identified, I discovered that approximately one in three coins had been previously recorded. When my record grew to 150 1794 half dollars, one out of every two observations had been already listed. During the survey, I took great pains not to visit the same dealer or collector twice about the same coin, as that would not be a separate observation. If the coin changed hands and I identified it a second time with a different owner, then that was a new sighting and an already- seen coin for the purpose of my statistical evaluation. When I wrote the book in 1980, I had seen 201 1794 half dollars and at that time I estimated that the chances were about 2/3 that the next coin observed would have already been examined.

A reasonable parameter for estimating the extant number of 1794 half dollars was thus determined. On the basis of my survey, there must be about 300 1794 half dollars in existence. I am of course measuring the coins that are in the marketplace and in exchange among collectors. If one has been salted away in a safe deposit box for the past 50 years, it will have been missed. Nevertheless, the vast majority of the 1794 half dollars in existence are in circulation, so that a safe extrapolation is a total field of approximately 317 specimens of the 1794 half dollar (see fig. 4, below).

The mint records reveal that delivery Warrant no. 1 was for 1,758 silver dollars, delivered on October 15, 1794. The first half dollar warrant, Warrant no. 2, for 5,300 half dollars was on December 1, 1794. Warrant no. 3 for 18,164 half dollars was on February 4, 1795. It has generally been assumed that this latter delivery was all 1794 half dollars, since there are too many 1794 half dollars to assert that the only 1794 delivery of 5,300 coins comprised all of the 1794s that were minted. Walter Breen and a great many other researchers have long since concluded that the second delivery was probably also 1794 half dollars. No one, however, substantiated this assumption. Nevertheless, if this theory is correct, the number of 1794 half dollars (5,300 from the December 1, 1794 delivery and 18,164 from the February 4, 1795 delivery) totals 23,464 coins. The first two chains reveal that 1-A and 1-B would probably be the 5,300 coins that were delivered in 1794. In my 201 observations of 1794 half dollars, the 1-A variety occurs 30 times, the 1-B 15 times. These varieties comprise 45 of the 201 observations or 22.38% (see fig. 3). Mathematically, the 5,300 coins equal 22.58% of the first two deliveries of 23,164 coins. Similarly, the second chain of Group I comprised 77.62% of the total by observation and the second delivery of 18,164 coins equals 77.41% of the mathematical total. This strong statistical correlation is ample proof that the first two die chains comprised the first two deliveries of Flowing Hair half dollars.

1794 HALF DOLLARS (GROUP I)

Figure 3

a As of January 10, 1980.

The Bank of Maryland made the first deposit of silver to the United States Mint in July 1794. By law, that bullion was to be coined and returned, at no expense, before any other coinage could take place. The first payment record is the memorandum of March 12, 1795.4 Since this was a memorandum of payment rather than a receipt, the Bank of Maryland representatives must have come to the mint and received a partial payment of 90,932 half dollar coins. According to mint delivery records, Warrant no. 4 for 60,660 coins took place on March 3, 1795- Warrant no. 5 for 46,808 coins is dated March 30. The Bank of Maryland must therefore have received all the coins struck by the mint from their deposit up to March 12, 1795.

An analysis of these facts yields important results. Of the initial output of 23,464 coins, 317 1794 half dollars survive. A survival rate of 1.35% is established. By inversion, statistically, one out of every 74.074 half dollars struck will exist today. Using that same ratio and estimating the number of coins in the 1795 series for each die variety in their proper sequence, the dies that should have been in the press when the Bank of Maryland received payment was the pair 11-E. This pair, together with 12-E, will have struck coins in the range of 90—95,000 from the inception of the half dollar mintage, according to the sequence. The 11-E die pair produced the only known coin of 1794 or 1795 where there is a so-called proof presentation piece. Walter Breen places the coin early in 1795,5 but that coin has been flashed, and the reverse die was well used by the time it was paired as 11-E. It was definitely not one of the first 1795 half dollars. I propose that it was a special coin struck at the time the Bank of Maryland officials arrived at the mint to pick up the first payment of silver coinage issued by the mint. The presentation piece was struck by the dies in use on March 12, 1795, namely, the 11-E pair.

Robert Julien has discussed the assay commission—s work during the early years of the mint—s operation.6 By law, coins were to be withdrawn from each batch of silver and reserved for assay by the commission. A minimum of three coins were required to be selected. Julien—s reconstruction of those assay coins indicates that periodically only two coins were saved. Correlating Julien—s selections for assay with my groupings, I observed that two half dollars in the last die chain were missing and, according to Julien—s assay coin list, only one coin reached the commission from the last die chain. Two other coins should have been reserved, but never reached the assay commission.

On October 13, 1964, in a Christie—s sale in London, a group of coins were auctioned identified as the coins originally obtained from the U.S. Mint by the Major the Lord Saint Oswald. As a youth of 19, during a tour of the United States, he visited the mint and received a number of coins as a souvenir. He received two 1794 silver dollars, a 1795 silver dollar of the early 1795 sequence, and two half dollars. The two half dollars, which he received, were the two assay pieces missing from Julien—s sequence and from the last die chain. These two half dollars thus provide further substantiation for the proposed 1794—1795 sequence.

Additionally, in Group V, there is one remaining unknown reverse die, identified above as the hex die. The next series of half dollars represents the beginning of the Bust type coinage. To complete three sets of dies, only three obverses and two reverses were needed, since one reverse (hex) would have been carried over. But, since the large silver dollar press was constructed in 1795 and dollars began to be produced in May, the production of half dollar planchets probably ceased in mid-April 1795. This cessation of half dollars lasted for two years. From 1795 until 1797 mint records show that no half dollars were made during the period mid-1795 until 1797. This information confirms the carryover of the hex die and provides further proof of the group strength theory.

The three die sets that comprise the first group of 1796-dated halves include both 15 and 16 star varieties of the coins. These varieties can be explained by examining the employment of John Smith Gardner. On March 30, 1795, Gardner left his position as assistant engraver due to a pay dispute. Nevertheless, he returned to the mint on July 1, 1796, and worked for exactly 50 days until August 26, receiving $3 as a daily wage. Evidently, there was a specific reason for bringing Gardner back for just 50 days. A probable explanation is that the Bust half dollar sequence was begun in the first quarter of 1796, and Gardner had made the first two dies for the obverse with 15 stars before leaving on March 30. During Gardner—s absence, the entire responsibility of engraving dies would have been thrown upon Robert Scot, and work stopped on the half dollar dies. When Gardner returned to the mint on July 1, Tennessee had just joined the Union as the 16th state on June 1, 1796. Gardner therefore finished the third die as a 16 star 1796 half dollar.

At the end of 1795 the mint had usable dies in almost all denominations, which continued to be used even though they bore the wrong date. This led to the decision to engrave dies without the last digit of the year. The engravers thus made multiple dies of each denomination, completing the dies with the exception of the last digit. The first obverse die in the Bust series was complete, except for the last digit; the second and third were completed as 1796 dies. Some complete dies would obviously be needed in stock.7 The problem is that the hex die, which completes this sequence, is not known with those half dollar obverses. The reason is that the first delivery of half dollar—s which took place after the 1795 deliveries was made on February 28, 1797, and it consisted of only 60 coins. This delivery would have contained the die combination of the second obverse die and the hex die. With a 60 coin delivery and a survival rate of 1 in 74 coins, it is unlikely that any of these coins have survived in circulation and come down to us today.

As this survey has indicated, and as I have detailed at much greater length in my book, the engraving of dies was not an arbitrary process. The mint officials conscientiously built an inventory of working dies in each denomination and rebuilt the group to its proper group strength when the supply was used. From this organization of the dies, it is possible to locate every single known die of every denomination of these early coins.

| 1 |

Robert P. Hilt II, Die Varieties of Early United States Coins (Omaha, 1980).

|

| 2 |

A1 C. Overton, Early Half Dollar Die Varieties, 1794—1836, rev. ed. (Colorado Springs, 1970); M.L. Beistle, A Register of Half Dollar Die Varieties

(Shippensburg. PA, 1929).

|

| 3 |

The delivery records are simply a record of coins delivered by the Chief Coiner to the Treasurer of the Mint and, in essence,

they

constitute the coiner—s receipt. They usually follow the actual minting of coins by some length of time—a day, a week—in some

instances, it

could be a few months. Nevertheless, they do provide some chronological indication of the sequence and quantity of coins that

were

made.

|

| 4 |

R.W. Julian, —The 1795 Silver Coinage: Half Dollars,— Numismatic Scrapbook Magazine 1963,

pp. 2521—24.

|

| 5 |

Walter Breen—s Encyclopedia of United States and Colonial Proof Coins, 1722—19 77 (Albertson, NY, 1977), p. 32.

|

| 6 |

—The United States Assay Commission—to 1817,— Numismatic Scrapbook Magazine 1964, pp. 289—92.

|

| 7 |

See Hilt (above, n. 1), pp. 39—40.

|

Coinage of the Americas Conference at the American Numismatic Society, New York

— The American Numismatic Society, 1987

At an ANA convention in the early 1970s Paul Munson mentioned that he had developed an emission order for the 1801 to 1807 half dollars by using edge links. He suggested that the authors try his method for the capped bust series of 1807 to 1836. The project, begun in 1975, has been more successful than we could have anticipated.

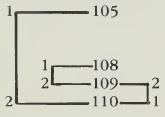

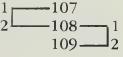

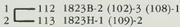

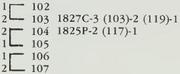

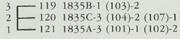

There were four hubs prepared for early half dollars (see fig. 1).1

The first, which contained five ornaments between FIFTY and CENTS, was used from 1794 to mid-1975 producing 5 edge dies that edge-lettered approximately 30,000 coin blanks or planchets each. The second, which had three stars between FIFTY and CENTS, through 1806 producing 14 edge dies lettering 100,000 each. All of the edges from this hub exhibit a broken second star. The third, which was devoid of ornamentation, from 1807 to 1814, produced 35 edge dies lettering 270,000 each. The fourth, with a star after DOLLAR, through 1836 produced 241 edge dies lettering about 300,000 each.

The hub, with its incuse lettering, was hardened and placed in the screw press opposite a softer steel bar. Several strokes of the press were required to force the steel into the recesses of the hub to create the working die. Most edges exhibit a shift of the hub or the recipient die between strokes, resulting in doubling or tripling within the confines of the letter, not of the letters per se, as in doubled edge lettering.

Each working edge die was composed of two bars; the first contained FIFTY CENTS OR; the second, HALF A DOLLAR. Each bar was hubbed separately as many edges show doubling on one bar opposite to the doubling on the other. The two bars were always inserted as a pair into the edge-lettering, or Castaing machine, to form the edge die. Of the 552 working die bars known for the capped bust series, there are only 85 or 15% which have no evidence of hub doubling; 274 or 50% exhibit doubling on the left side; 174 or 32% show right side doubling, and 19 or 3% other hubbing errors. Fig. 2 demonstrates varying amounts of hub doubling on the left side. The top coin exhibits very little doubling, but the doubling increases with each edge until it reaches the entire width of the letters on the bottom coin. Note that the doubling is within the letter. Fig 3 illustrates examples of doubling on the right side, again from slight to full letter.

There are also 9 each of triple-hubbed edges. Although there is no clearly defined example of a quadruple-hubbed edge, in 1985 Gunnet found an 1809 that had an edge we had never seen. It is the —Spanish steps— of the early half dollar edge world.

Fig. 4 illustrates a coin that shows a definite quintupling on the left side. We hesitate to claim that this die was struck five times in the hubbing process, but have no other explanation. Perhaps one or two of the steps are the result of machine doubling, but we have never seen another machine-doubled edge or we haven—t been able to recognize it.

Fig. 5 indicates the correct starting position for a planchet that will receive its full complement of edge letters in the Castaing machine.2 As the crank is turned, the sliding die moves the planchet between the two bars in their entirety, upsetting the rim simultaneously so that the struck coin will have full borders. Fig 6 demonstrates the cause of a blundered edge reading FIFTY CENTS OR A DOLLAR.3 The incomplete retraction of the sliding die is the cause of missing and overlapped letters. In this case the sliding die had not been fully returned to its proper starting position when the planchet was inserted, so the word HALF was missed.

In addition to the foregoing very common blunders, there are other more interesting errors to be found on these edges. They comprise the multiple edge-lettered type of error.

The word CENTS is doubled in fig. 7. The operator probably realized the planchet was started incorrectly, released the planchet and re-inserted it with the crank in the proper position. Fig. 8 displays the most spectacular edge blunder we have seen—fully tripled, nearly perfectly aligned, edge lettering This planchet was not released after being lettered, was drawn back through the bars and passed through again. This coin is the only one observed that shows this phenomenon. In fig. 9, the coin was lettered but for some reason placed back in the machine with the opposite side upward and run through again. The result is that the word DOLLAR has an upside down HALF superimposed over it.

A phenomenon that edge dies share with obverse and reverse dies is die cracks. The force required to letter and upset the edge of the planchet often caused the edge dies to break, just as the force of striking the planchets into coins caused the obverse and reverse dies to crack. Fig. 10 illustrates coins with a heavy die crack at the upper edge, a crack in the center, and at the lower edge.

The question most asked is —how do you tell the edges apart?— It is an indisputable fact that each of the 295 edges is different from any other. Separating sharp new edges that show multiple hubbing to varying degrees is simple as are those with die cracks. The edges of 1831 to 1836 are easy to distinguish because the reeding applied to each die varies in amount, width and depth. It is more difficult to separate edges that do not have outstanding features. When the die is hubbed, the metal flows into the letter recesses to different depths causing deeper and shallower areas, which can be discerned. Some letters may contain chips, lines or other irregularities that make them distinguishable. These are easily linked to others with the same configuration. Progressive deterioration of the die can be followed and, with experience, anticipated.

The most difficult part of an edge study is comparing an early die state edge to a very deteriorated one. No one could possibly anticipate that the two edges of fig. 11 were produced by the same die. The D and O on the early die state edge show distinct hub-doubling on the right and several heavy horizontal lines. The top and bottom of the first L are much deeper than the very shallow stand. The late die state edge displays none of these characteristics.

Fig. 12 illustrates a mid-die state edge that clarifies the relationship between the early and late state edges. The middle edge not only retains the doubling and lines of the early edge, but also shows the beginning of the breakdown of the lower part of the letters similar to the late edge.

The foundations for establishing the emission order for early half dollars was edge die linkage and states and obverse and reverse die linkage and states. The pairing of an obverse die and a reverse die created a die variety or die marriage. As the study progressed, it became increasingly apparent that edge die linkage was more important than obverse and reverse die linkage. In no instance, however, was an edge link used to contradict a marriage die state.

The average edge die life was much longer than the average die marriage life. Since there was no correlation between the edge dies and the marriage dies, it was inevitable that in most cases the same edge die was used for several consecutive marriages or that many marriages will exhibit two or more different edges. By examining many thousands of coins, we have been able to find a link of two edges within the same marriage in all but three instances in the draped bust series, and in all but six in the capped bust series.

Until 1824 the edge links and states coincide almost perfectly with the marriage links and states. This indicates that the planchets were struck as they came from the Castaing machine and that there was strict inventory control. As production increased in later years, there is more mixing of the marriages and edges. At times the emission order becomes blurred, but it is still discernible.

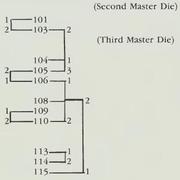

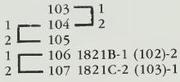

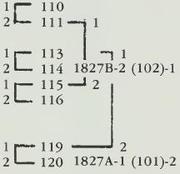

The methodology of the emission charts which follow is explained in the introduction. Here we wish to touch on several interesting points revealed by the analysis. Reference is to the year-dated charts.

1807: In the last column (emission order equals EO), the line indicates a break in the edge links, the first of six such breaks. We have been unable to find a late die state 114 with the third edge or an early die state 111 with the second edge. The third edge hub was initiated at the beginning of 1807 and used for both the draped bust and capped bust halves.

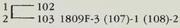

1809: This diagram contains a feature not shown in 1807—the sharing of a reverse die with a marriage of a succeeding year. DMs 107 and 108 share a reverse die with 1810—103. The 1809s were struck before the 1810.

Three of the 1809 edges bear ornamentation and are called the —experimental edges.— The third edge exhibits heavy vertical grooves at the beginning of each bar in front of FIFTY and HALF. The fourth edge is called the —engrailed— edge. There is a series of X-like figures at the front of the first bar and at the end of the second. The sixth edge contains only 106. There are light grooves in front of HALF. We call this the —pseudo-engrailed— edge. Fig. 13 illustrates the third edge with the vertical grooves, the —engrailed— fourth edge, and the —pseudo-engrailed— sixth edge.

1814: This chart is interesting for two reasons—a change in the edge hub and an edge out of sequence. The first and second edges were produced by the third hub of 1807. The fourth hub with a STAR after DOLLAR was used for others and for the rest of the series.

The 103 in the third edge caused great frustration because it does not belong there. It should be in the sixth or seventh edge with all the other 103s. This is the only instance seen in the entire series in which a planchet was struck sometime after being lettered, probably several months.

1826: This is noteworthy because of its complexity, with the use of so many edges and the appearance on the diagram of a new feature—the sharing of a reverse die with a marriage of a previous year. DM 104 shares a reverse die with 1825—117; the 1825 was struck first.

The 1826 mintage was only about 30% higher than 1825, but more than twice as many edges were used. The average edge die life in 1825 was 230,000 planchets; in 1826, only 140,000. No edge contains more than three die marriages—102 and 109 each exist with five different edges; 101 and 117, with four. It was difficult to find an edge on these four marriages that matched another marriage for a link.

1827: Although the diagram of the 49 marriages in 1827 appears difficult, it was one of the earliest emission orders tentatively confirmed. Only five marriages are not die-linked to another and one of those—140—is die-linked to 1828-104. Most of the rest of the marriages are linked together in large groups that could be aligned by obverse and reverse die state.

Most of the edges contain many marriages, although they are somewhat mixed. These two factors combined to make formulating the emission order simple. Here is the last of the six missing edge die links. The dl denotes that 109 and 110 are die-linked to each other. The other four missing edge links occur in 1811, 1819, 1820 and 1825.

1830: In this year the mint began experimenting by adding various types of reeding to the edge dies resulting in three types of edges being found in this year. The first five edges are a continuation of the plain-lettered edge used since 1814. The next two edges bear fine diagonal lines slanting down to the right. The rest all have lines slanting down to the left. These lines were not merely engraved into the die, rather rectangular areas were removed from the die leaving the grooves. The 1830 edges should be called —experimental,— not those of 1809. Fig. 14 exhibits the plain edge of the first five edges, the slanted to right reeding of the sixth and seventh, and the slanted to left reeding of the eighth through the sixteenth.

1831: In this year there are also three distinct edge types, but only one is the same as in 1830. The first six edges show the slanted down to the left type found on the later 1830s. The seventh edge is a transitional one that exhibits the former type, with the reeded areas relieved in all areas except at the beginning of the first bar. In front of FIFTY is a large area of fine vertical lines from top to bottom that were engraved directly into the die without the hollowing out as previously done.

This rare edge type was used for a portion of five die marriages. The balance of the 1831 edges contain heavy vertical reeding engraved in hollowed out rectangles. This edge type was adopted and all of the edges through 1836 exhibit these vertical grooves of varying placement, depth and width, except edge 14 of 1836. Fig. 15 shows the slanted reeding of the first edges, the transitional edge, with slanted lines appearing in front of the star and the vertical lines in front of FIFTY, and the adopted type with all vertical reeding.

1836: This is a very difficult year, but we think the emission order is correct. Many of the marriages are not die-linked and they are quite scattered throughout the edges.

It appears the mint began to stockpile lettered planchets for the first time, causing the almost random appearance of many marriages. Edge 14 is the plain lettered edge referred to previously. Fig. 16 compares a normal reeded edge with edge 14. This plain edge, which is found on one 1834 and three 1836 marriages, has led many catalogers to claim that these coins were struck on older planchets.

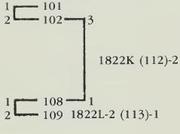

The numbers in the first two columns—Die linked/state and Nondie-linked—are die marriages (DM) listed in Overton number order (except where there is a master die change during the year).4 Those in the Die linked/State column are the DMs which share either the obverse or reverse die with another DM of that year. The obverse die linkage and die state are represented by the numbers in front of the O number; the reverse by those in back of the O number. Those in the Non-die-linked column are those DMs which do not share a die with any other DM of that date, but may share the reverse die with a DM of another year. Edge dies have nothing to do with these two columns.

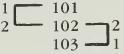

An example (1817):

| Die linked/State | Non-die linked |

|

|

| 112 |

Here 112 has no die link to any other DM; 107 and 108 share the same obverse die—the 1 and 2 mean 107 was struck before 108 by die state; 108 and 109 share the same reverse die with 108 being struck before 109 by die state.

A more complex example (1810) follows, but the same method is used:

| Die linked/State | Non-die linked |

|

Here 102 was struck before 103 by observe die state; 103 shares a common reverse (1809F) with 1809—107 and 108. By reverse die state, 1809—107 was struck before 1809—108 and 1809—108 was struck before 1810—103.

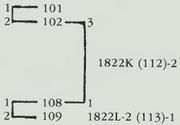

The most difficult example (1823) follows:

| Die linked/State | Non-die linked |

|

|

| 103 | |

| 104 | |

| 105 | |

| 106 1824M-1 (114)-2 | |

| 107 |

Here 101 was struck before 102 and 108 before 109; 102 and 108 share a common reverse (1822K) with 1822—112; 108 was struck first, 1822—112 next and 102 last. DM 109 shares a common reverse (1822L) with 1822—113 and 113 was struck before 109; 103, 104, 105 and 107 have no die link to any other DM; 106 shares a common reverse (1824M) with 1824—114 and 106 was struck first.

The second section—Edges—pertains only to edge dies and these are numbered in the order they were used in the Castaing machine. Under each edge number the DMs that share the same edge die are listed in descending order by edge die state from the first use of the edge die to the last. The edges in each year are listed until the first DM of the next year appears. The last edge of one year is carried over as the first edge of the succeeding year.

The third section—Edge Order—is merely a recapitulation of the second section arranged vertically and corrected to reflect the obverse and reverse die states as struck. A line between groups separates the edge dies.

The EO section is just that—the emission order compiled by a combination of obverse and reverse die linkage and states and edge die linkage and states. A line between groups indicates a break in the edge links; dl next to an entry denotes an obverse or reverse die link between the DM immediately adjacent and that immediately below; () indicates DMs that were struck in a succeeding year and have no edge connection within the year they are dated.

| Die linked/State | Non-die linked | |

| (Draped Bust) | ||

|

||

| (Capped Bust) | ||

|

113 | |

| 114 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 108 | 105 | 111 | 112 |

| 109 | 107 | 112 | 1808—101 |

| 110 | 106 | 1808—110 | |

| 105 | 101 | 1808—108 | |

| 102 | |||

| 104 | |||

| 103 | |||

| 113 | |||

| 114 |

| Edge Order | EO |

| 108 | 108 |

| 109 | 109 |

| 110 | 110 |

| 105 | 105 |

| 105 | 107 |

| 107 | 106 |

| 106 | 101 |

| 101 | 102 |

| 102 | 104 |

| 104 | 103 |

| 103 | 113 |

| 113 | 114 |

| 114 | 111 |

| 111 | 112 |

| 112 | 1808—101 |

| 112 | 1808—110 |

| 112 | 1808—110 |

| 1808—101 | |

| 1808—110 | |

| 1808—108 |

The outside point of star 13 is scalloped on all.

| Die linked/State | Non-die linked |

| 101 | |

| 102 | |

| 103 | |

| 104 | |

| 105 | |

| 106 | |

| 107 | |

|

|

| 110 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1807—112 | 108 | 103 | 102 | 106 |

| 101 | 109 | 102 | 104 | 1809—112 |

| 110 | 103 | 104 | 107 | 1809—113 |

| 108 | 105 | 1809—114 | ||

| 106 | 1809—115 | |||

| 1809—111 |

| Edge Order | EO |

| 1807—112 | 1807—112 |

| 101 | 101 |

| 110 | 110 |

| 108 | 108 |

| 108 | 109 |

| 109 | 103 |

| 103 | 102 |

| 103 | 104 |

| 102 | 107 |

| 104 | 105 |

| 102 | 106 |

| 104 | 1809—112 |

| 107 | 1809—113 |

| 105 | 1809—114 |

| 106 | 1809—115 |

| 106 | 1809—111 |

| 1809—112 | |

| 1809—113 | |

| 1809—114 | |

| 1809—115 | |

| 1809—111 |

The second obverse and reverse master dies were engraved this year. All marriages were struck from dies made from the new hub.

The upper inside point of star 13 is scalloped on all.

| Die linked/State | Non-die linked |

|

106 |

| 111 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1808—106 | 111 | 111 | 108 | 102 | 106 | 106 |

| 112 | 109 | 101 | 104 | 1810—101 | ||

| 113 | 107 | 110 | 105 | 1810—102 | ||

| 114 | 108 | 102 | 103 | |||

| 115 | 106 | |||||

| 111 |

| Edge Order | EO |

| 1808—106 | 1808—106 |

| 112 | 112 |

| 113 | 113 |

| 114 | 114 |

| 115 | 115 |

| 111 | 111 |

| 111 | 109 |

| 111 | 107 |

| 109 | 108 |

| 107 | 101 |

| 108 | 110 |

| 108 | 102 |

| 101 | 104 |

| 110 | 105 |

| 102 | 103 |

| 102 | 106 |

| 104 | 1810—101 |

| 105 | 1810—102 |

| 103 | |

| 106 | |

| 106 | |

| 106 | |

| 1810—101 | |

| 1810—102 |

| a |

See above, p. 48, for description and illustration of the experimental edges: 3 (vertical grooves); 4 (engrailed); 6

(pseudo-engrailed).

|

The outside point of star 13 is scalloped on 101—4, 106—7, 109. The upper inside point of star 13 is scalloped on 105, 108, 110.

| Die linked/State | Non-die linked |

| 101 | |

1809F-3 (107)-1 (108)-2 1809F-3 (107)-1 (108)-2

|

|

| 104 | |

| 105 | |

| 106 | |

| 107 | |

| 108 | |

| 109 | |

| 110 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1809—106 | 102 | 106 | 106 | 106 | 108 |

| 101 | 103 | 105 | 104 | ||

| 102 | 110 | 109 | 1811—101 | ||

| 106 | 107 | 1811—111 | |||

| 108 |

| Edge Order | EO |

| 1809—106 | 1809—106 |

| 101 | 101 |

| 102 | 102 |

| 102 | 103 |

| 103 | 110 |

| 110 | 106 |

| 106 | 105 |

| 106 | 105 |

| 106 | 109 |

| 106 | 107 |

| 106 | 108 |

| 105 | 104 |

| 109 | 1811—101 |

| 107 | 1811—111 |

| 108 | |

| 108 | |

| 104 | |

| 1811—101 | |

| 1811—111 |

The outside point of star 13 is scalloped on all.

| Die linked/State | Non-die linked |

|

104 |

|

108 |

|

111 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1810—108 | 111 | 110 | 104 | 104 | 109 |

| 1810—104 | 110 | 108 | 112 | 112 | 105 |

| 101 | 108 | 103 | 113 | 107 | |

| 111 | 102 | 109 | 1812—101 | ||

| 106 | 1812—102 | ||||

| 105 |

| Edge Order | EO |

| 1810—108 | 1810—108 |

| 1810—104 | 1810—104 |

| 101 | 101 |

| 111 | 111 |

| 111 | 110 |

| 110 | 108 |

| 108 | 103 |

| 110 | 102 |

| 108 | 104 |

| 103 | 112 |

| 102 | 113 |

| 104 | 109 |

| 112 | 106 |

| 104 | 105 |

| 112 | 107 |

| 113 | 1812—101 |

| 109 | 1812—102 |

| 109 | |

| 106 | |

| 105 | |

| 109 | |

| 105 | |

| 107 | |

| 1812—101 | 1812—102 |

The obverse master die was reengraved at the beginning of this year and a new hub was made. The curls are coarser and the relief is higher at the shoulder and breast. This hub was used for all of 1812 except 101—2 and until 1817.

The outside point of star 13 is scalloped on all.

| Die linked/State | Non-die linked |

|

|

| 103 | |

| 104 | |

|

|

| 109 | |

| 110 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1811—109 | 102 | 109 | 103 | 107 | 108 | 105 |

| 1811—105 | 110 | 103 | 104 | 108 | 105 | 106 |

| 1811—107 | 109 | 107 | 1813—103 | |||

| 101 | 1813—101 | |||||

| 102 | 1813—102 |

| Edge Order | EO |

| 1811—109 | 1811—109 |

| 1811—105 | 1811—105 |

| 1811—107 | 1811—107 |

| 101 | 101 |

| 102 | 102 |

| 102 | 110 |

| 110 | 109 |

| 109 | 103 |

| 109 | 104 |

| 103 | 107 |

| 103 | 108 |

| 104 | 105 |

| 107 | 1813—103 |

| 108 | 1813—101 |

| 108 | 1813—102 |

| 105 | |

| 105 | |

| 106 | |

| 1813—103 | |

| 1813—101 | |

| 1813—102 |

The outside point of star 13 is scalloped on all.

| Die linked/State | Non-die linked |

|

106 |

|