One of the by-products of the growth of the British Commonwealth has been the gradual evolution of a far-reaching system of public honors. The custom of rewarding public service by granting some distinction or title to the individual is neither new nor characteristically British. Until the beginning of the nineteenth century, however, such honors were generally reserved for persons of great rank and station. In all the countries of Europe it had long been the custom to reward the services of the wealthy and of the nobility by the granting of hereditary titles, or the admission to such select organizations as the Orders of the Garter and the Golden Fleece. It remained for Great Britian to adapt a custom which, in the years before 1800, had hardened into a means for perpetuating class distinctions, to the new political and social realities that faced her during the nineteenth century. So successful was the adaptation that today people in all walks of life, without regard to wealth or position, have the opportunity of winning public recognition for services rendered to the State, to their communities, or to society as a whole. Titles of hereditary nobility are still granted, but the greater part of the honors now available take the form of a distinguishing Order, decoration or medal. It will be the purpose of the Monograph to considef these latter.

In a system so extensive as that of British public honors a considerable degree of complexity has naturally developed. The medieval and the modern exist side by side and each partakes to some degree of the characteristics of the other. The Order of the Garter is still the most exclusive distinction in Europe. But in recent years it has seen admitted to its membership, along with Kings and Princes, a gentleman whose fortune was made manufacturing screws in Birmingham, and another whose political career was made possible by considerable success in the iron and steel industry. At the same time the Garter is the direct ancestor of the Order of the British Empire founded in 1917, one of the most widely bestowed and yet widely respected of the Orders. As the number of individuals eligible for recognition increased it became necessary to classify rigidly the type of service for which certain honors are given. In the armed services, junior officers and enlisted men in line of duty in time of war normally are faced with situations justifying the award of one of the decorations for valor such as the Victoria Cross or the Distinguished Service Order. On the other hand, senior officers, whose activities involve great responsibility and do not normally bring them face to face with the enemy, are recompensed with one of the higher grades of the Orders of Knighthood not usually available to the junior officer. There are also certain decorations, as in the case of the D.S.O., reserved entirely for officers, and others granted only to enlisted men. Both groups are granted for exactly the same type of service. Civilians of all classes, not eligible for a military decoration, can be awarded one of the grades of an Order, or in time of war, the George Cross. Statesmen, diplomats, and colonial administrators all in due time are admitted to one of the Orders which are generally bestowed on men who make their mark in the civil, diplomatic, or colonial Services.

If the functions of an Order and a decoration are to be properly distinguished, one from the other, it will be necessary to review briefly the history and characteristics of each and the conditions which govern their award. The word "Order" is itself misleading. In its beginnings the Order of the Garter was constantly referred to as the "Society of St. George" or the "Fraternity of St. George called the Garter." As late as 1783 when the Order of Howland Wood> was founded it was called the "Society and Brotherhood of the most Illustrious Knights of Howland Wood>." The circumstances surrounding the founding of the Order of the Garter are obscure, but what we know only serves to emphasize its organized and fraternal aspect. An Order was essentially a group of men banded together for a specific purpose. That purpose could be either religious, as in the case of the great Monastic Orders, or military and political, as it was in the cases of most of the Orders of Knighthood founded after 1350. Certainly by the middle of the fourteenth century the Garter existed in a form that was to be the guide for all other Orders subsequently founded in England. The characteristics of an Order as it emerged from the Middle Ages were fourfold: it was a fraternal organization; the number of members was specifically limited by the laws that controlled it; each member was a Knight regardless of his other rank or station; each member wore some distinguishing badge signifying his membership.

In the course of time, the fraternal aspect of the Orders all but disappeared in Europe. The London Times observed editorially in 1913, "It was during the nineteenth century that the strange custom arose of saying that 'a man was wearing his Orders.' The conception of most people in that sometimes prosaic period was that the decoration worn by the members of an Order was the 'Order' itself. The idea had little to disturb it in this country. Nothing was done to remind the members of British Orders that they were in fact associated in a confraternity having rules and a corporate existence of its own .... King Edward VIII reverted to the ideal of Chivalry and authorized those of his subjects, who were properly qualified, to meet in Church in order to take part as members of a Knightly fraternity in a corporate service of thanksgiving and dedication." The subordination of the associational characteristics which the Times complained about can be traced partly to the vital changes in the organization of some Orders and partly to a great increase in their numbers and availability. Until 1815 it was the general rule that no British subject could belong to more than one British Order. Even when the Duke of Wellington was given the Garter in 1813 he had to resign the Bath. With the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, the government was faced with the problem of providing some means of rewarding the large number of officers who had distinguished themselves but whose services were not important enough for them to be considered eligible for admission to membership in one of the four available Orders. The solution of the difficulty that was reached was based partly on previous Continental examples and partly on expediency. The Order of the Bath was divided into three classes. Each class was limited in numbers, but only the first two carried the honor of Knighthood. The change raised the membership of all British Orders, in round figures, from 100 to 800 in the period of a year. But, however revolutionary such a step may have appeared at the time, the next century was to see the foundation of five new Orders of Knighthood, each one with several classes and divisions, three Orders not carrying the honor of Knighthood, all the decorations of valor, and a host of miscellaneous medals for the reward of every conceivable type of public service. Add to these the large number of similar foreign distinctions that at one time or another have become available, and it is not surprising that the old Medieval corporate spirit that originally played so important a part in an Order of Knighthood was completely lost.

In spite of the multiplication of Orders of all kinds, the most important and perhaps the most significant and interesting development in the field of honors in the nineteenth century was the gradual evolution of the decoration given for individual valor. The conditions governing the bestowal of a decoration approached the reverse of those governing an Order. A set of rigid standards was established. All men who could meet those standards became, in theory, eligible to receive the decoration. Strange as it may seem, there was no distinction available for the junior officer or enlisted man before 1845. During the Napoleon ic Wars high-ranking officers were given gold medals for the battles and engagements in which they participated. But these medals were not distinctive decorations since they were granted generally to all officers of a certain rank present in an action. They were the immediate predecessors of the line of campaign medals eventually issued to all ranks throughout the century. The services of the enlisted men were not, except in the abstract, recognized as being worthy of any particular note by the authorities. It was left to the Honorable East India Company to lead the way. In 1837 two decorations were established to be granted for distinguished service and for gallantry to their native troops. It was not until 1845 that the Meritorious Service Medal was instituted—a decoration that was replaced in 1854 by the now famous medal "For Distinguished Conduct in the Field," granted exclusively to non-commissioned officers and men for gallantry in action. The position of the officers was finally recognized when all ranks were made eligible for the Victoria Cross in 1856. The small wars incident to the growth of the Empire and finally the Great War further expanded this list to the point where it can be said that adequate awards are available for each branch of the armed forces. Nor did valor essentially unmilitary in nature go unnoticed. The so-called "Civilian Victoria Cross," the Albert Medal, was established in 1866 for saving life on land and sea. It bears the distinction of being, with the exception of the recently created George Cross, the most sparingly bestowed of all British Decorations.

The distinctions so far discussed have all had one characteristic in common. The majority of them have been made available for services to the State in a civil, diplomatic, or military capacity. For a long time employment in the military or administrative branches of the state was considered the only form of activity that merited public recognition. There was no means of recognizing purely cultural activities and, above all, no means of recognizing services performed by women. Queen Victoria found that there was no decoration she could give to Florence Nightingale for her unselfish devotion to nursing the wounded in the Crimea. She solved the problem by presenting Miss Nightingale with an ornmental jewelled and enamelled brooch. The premier decoration for military nurses, the Royal Red Cross, was not established until 1883. This refusal to provide for women was all the more curious because a very good precedent exists in the Order of the Garter itself. There were Ladies of the Order in the first century and a half of its existence. Titled ladies were moreover recognized by the creation of the court Order of Victoria and Albert, and the Order of the Crown of India. But it needed the upheaval of the World War before the services of women were generally recognized to the extent that provision was made for them in the newly founded Order of the British Empire and the Order of the Companions of Honor. The Arts and Sciences were in exactly a similar position until the Royal Victorian Order, the Order of Merit and the Order of the British Empire were adapted to recognize musicians, sculptors, scientists and literary people.

The multiplication of honors of all kinds caused their distribution to become an increasingly difficult problem. Before 1815, when every proposed recipient was a gentleman of rank, he was generally personally known to the Sovereign, who was thus able to judge his fitness for the distinction. Down to the end of her reign Queen Victoria required her Ministers to submit a brief biography and list of services of each candidate for admission to one of her Orders. But as late as the last decade of the century the New Year's and Birthday Honors Lists occupied only half a page in the London Times, whereas today they occupy one and a half to two pages in the same paper. It is manifestly impossible for the King to know all of even the most distinguished candidates or to make the same demands on his Ministers for information that Queen Victoria made. In fact the growth of the Honors Lists and the increasing control exercised by the Government over the granting of all honors has served to deprive the Sovereign of many of the powers he once exercised in this field. The Prime Minister now bears general responsibility for all the names on the Honor Lists. He is advised on those proposed for the Civil Service by the Permanent Under Secretary to the Treasury. The Defense Departments, the India Office and the Foreign Office have the right of submitting the names of their candidates directly to the King. While the Prime Minister has all but complete control over the honors system he functions, in fact, under many restrictions. The belief that all honors proceed from the Crown makes it almost impossible for him to propose or press an honor which would cast discredit on the Crown. When Charles James Fox once went so far as to promise a Knighthood of the Bath to a friend without consulting the King until the day of the Investiture, George III refused outright to bestow the honor. Queen Victoria had a very high regard for her powers in this respect and in the case of Lord Lansdowne bestowed a Garter over the direct opposition of Mr. Gladstone. Recent cases where the Sovereign's judgment in these matters has been overridden by his first Minister are very rare. It would be too much to say that honors are awarded only to those who deserve them. But in view of the size and complexity of the honors system the number that are bestowed on the undeserving is very small indeed.

The Orders of Knighthood may be divided into three broad groups for the purpose of discussing the circumstances affecting their distribution. The first of these comprises the Orders of the Garter, the Thistle, and Howland Wood>, which may be called the "Great Orders." The Orders of Merit, headed by the Bath, are six in number. The third group, composed of the Order of Merit, the Royal Victoria Order and the Order of the Companions of Honor, stands alone because they are largely free of political control. Of the Great Orders the Garter is the most representative example. In its long career it has been used as an instrument of government and diplomacy. The original Knights were close friends or advisors of Edward III. When strong Kings ruled, it was used as a reward for loyal and unquestioning service. When weak Kings occupied the throne, it was used as a prize to lure the support of strong vassals. As representative government grew and flourished it lubricated the cogs of the Parliamentary machine. Probably no better example of this function of the Order can be found than in a letter from Queen Victoria to Lord Derby in 1852. She wrote, "The Queen is of the opinion that it would be advisable on the whole to give the Garter to Lord Londonderry although the Duke of Northumberland has the best claim. At the same time the Queen would have no objection to bestowing it on Lord Lonsdale if this is desirable in order to facilitate any Ministerial arrangements Lord Derby may have in contemplation." Very frequently the Garter has been used in international diplomacy. The Anglo-French Alliance during the Crimean War was signalized by a full Chapter of the Order held at Windsor for the purpose of giving the Blue Ribbon to the Emperor Napoleon III. When the Shah of Persia visited England early in the reign of Edward VII the King refused to give him the Garter, although the oriental potentate made it quite plain that he wanted it. Some months later, however, when it became plain that the Shah's attitude would have an extremely important effect on the attempts of Britain to develop Persian oil fields the Garter was sent out with a special mission.

Any discussion of the Great Orders would be quite incomplete if it were confined only to diplomacy and high or low politics. The fact is that many men, distinguished and otherwise, have wanted the Garter for very human reasons. A recent biographer of Lord Chesterfield has written "What he wanted at this moment was the Order of the Garter, the premier decoration at the King's disposal, the most illustrious decoration in Christendom. Aside from everything else, it was a gorgeous ornament of dress, in a day when Knights of the Garter and the Bath put on their ribbons and Stars as a part of daily apparel. The broad blue ribbon expanded even a narrow chest; the blazing diamonds of the huge Star overwhelmed the least dazzled beholders with awe and veneration. Ambassador Chesterfield entering a salon without this splendor was relatively a little naked man compared with Ambassador Chesterfield clothed in such insignia. As he put it eventually to Sir Robert Walpole, ‘Iam a man of pleasure and the Blue Ribbon would add two inches to my size.' But primarily, of course, it was the symbolic character of these trappings that gave them their essential value. To be one of twenty-five selected from the entire nobility of England, to be one of an inner circle already 400 years old—the merit lay in this rigid exclusiveness."

Probably the ultimate in frankness was achieved by Lady Ashburton when she remarked in the fifties of the last century, "The Garter is about the only distinction left that those fellows of talent cannot gain. We don't like honors that are earned." The Order had long been a perquisite of the aristocracy, and the aristocracy surrendered its perquisites only under duress. It was Lord Palmerston's cynical judgment that the Knights had been chosen more often for their social standing than their deeds. While there is much truth in Lord Palmerston's remark, it must be remembered that the Order has inevitably reflected the age in which it found itself and the men who made use of it. There has been no British institution which has adapted itself more gracefully to changing circumstances than this Order has in the six hundred years of its existence. No one has ever put himself on record as being insulted when it was offered him, although Lord Shaftesbury very nearly insulted Queen Victoria by refusing it twice because he felt himself unworthy of the honor. While not always put to the best purpose, the Garter is still the most distinguished reward at the King's command for the man who has done his best and accomplished great things for England.

The group of decorations which have been loosely termed the Orders of Merit include all those commonly given to distinguished military and naval men, diplomats, and colonial administrators. Of these the Order of the Bath is most typical. All Orders subsequent to the Bath were organized on similar lines. According to the statutes, most of the members had to hold the rank of Captain in the Navy, Colonel in the Army, or a position of equal responsibility in the civil or colonial services before being admitted to the lowest class of one of these Orders. In practice, in time of peace very few officers receive the third class of the Bath until they are Rear Admirals or Major Generals. Since the outbreak of the present war, however, the Companionship of the Bath has been considered a fitting reward for the commanding officers of ships which have distinguished themselves in action. In the battle of the River Plate leading to the destruction of the Graf Spee, the Captains of the cruisers engaged were made Companions of the Bath while Commodore (later Admiral) Harwood was created Knight Commander in the same Order. It should be noted that the Orders of Merit are very frequently given to foreign officers engaged with British forces. Thus in the last war General Pershing received the Grand Cross of the Bath. Many officers will probably be admitted to various grades of the Orders of the Bath, Star of India and St. Michael and St. George, as a result of widespread American participation in the present war. Generals Eisenhower and MacArthur have already received the Military Grand Cross of the Bath.

Whenever one of the higher grades of an Order is conferred, if the recipient is not already a Knight it is necessary for him to be Knighted. He then has the right to bear the non-hereditary title of "Sir." This ceremony involves the actual physical contact of the sword laid on the shoulder by the Sovereign or his deputy appointed for the purpose. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries deputies were very frequently appointed. An example of this occurred when General Jeffrey Amherst was knighted and invested with the insignia of the Order of the Bath on Staten Island by Major General Monckton, Governor of New York City. Today, however, the recipient of an Order generally waits until he has an opportunity to go to the Palace to receive the insignia and the Knighthood from the Sovereign. When an Order is given to an American it is in the nature of a presentation. Since the Constitution prevents Americans from accepting foreign titles, they are not Knighted, although Congress permits them to accept foreign decorations in time of war. While the distribution of the Orders of Merit is severely standardized, there is one group of decorations over which the Government has very little if any control. The Order of Merit, Companions of Honor, and the Royal Victorian Order are the decorations most frequently given for purely cultural activities. They are the sole gift of the Sovereign, who may, but need not, accept his First Minister's advice in awarding them. The first two of these distinctions carry no title.

The distribution of decorations presents quite a different problem from the distribution of the Orders of Knighthood. While regulations have been drawn up defining the conditions under which a certain decoration will be granted, it is obviously impossible to catalogue specifically just which acts merit recognition and which do not. Each change in the art of war has produced a change in the standards for the award of every decoration. The tremendous sweep of the last war created a situation that the authorities were not prepared to meet. All Britain's previous wars had been small ones by comparison. They had been wars of cavalry and flags. The winner of a Victoria Cross was often the man who saved his regimental standard, or carried a wounded officer from the field under fire. There were no machine gun nests, muddy trenches or millions of participants to complicate matters. In an effort to prevent the wholesale shower of awards during 1914-1918, an allowance list was established for types of ships in the Navy and units of men in the Army. Unfortunately, the arrangement did not always function very well. Admiral Sir Roger Keyes records that "in Gallipoli we were told that these things must be adjusted by scale. Admiral Robeck could only have a certain percentage based on the number of people on the station to be divided in a fixed proportion between officers and men. The opportunities of winning distinction played no part in this ridiculous system of award by scale which those unimaginative people produced. In the Grand Fleet after Jutland where squadrons were similarly treated, it is no exaggeration to say that a squadron which had never been severely engaged received the same number of honors as one that had fought many battles with heavy casualties." It is interesting to note that a very similar system was inaugurated in 1939. The scale fixed for the Navy was one decoration for every 250 men in active service every six months. For shore duty the proportion was one for every 1000 men every six months. If there is any justification for Sir Roger Keyes‘ stringent criticism of the system of award by scale in 1915, it would seem that the same error might have been avoided. It is, no doubt, easy to find fault, particularly where there is no responsibility involved on the part of the critics. However, it is also very easy for a Government Department staffed with people who have had little experience with actual service conditions to reach decisions that are painfully at variance with reality. Unfortunately, it seems that in such cases the advice and comment of the man on the spot is very frequently ignored, as Admiral Keyes found. Decorations are also given to foreign troops associated with the British forces. There has been only one case, however, where the Victoria Cross was bestowed on an American and that was the Unknown Soldier.

An attempt has been made to explain the origin of Orders and decorations in Great Britain and the conditions under which they have been distributed. The story would be incomplete if it were not pointed out that the expansion of the system of public honors has had a very close relation to the forces that in the past three hundred years have made modern England. It was in this period that political end social democracy as it is known today was avolved. At one time admission to a British Order was the privilege of the aristocracy. Today it is the privilege of every British subject. The development of the honors system has so paralleled and mirrored other more important forces that today it exists not as a relic of a feudal past but as one of the living inheritances of England.

Each of the nine Orders of Knighthood was founded when some specific need arose that it could serve. Each was the product of an era, and each was tailored to fit a set of special circumstances. The origin of the Order of the Garter has been the subject of considerable controversy among historians and antiquaries for hundreds of years. All the earliest records of the Order have been lost, so that the evidence that exists is largely indirect. Certainly ideals of romantic chivalry which were so important in the middle of the fourteenth century made it possible for an organization of Knights, ostensibly dedicated to those ideals, to flourish. But the foundations of the Order did not lack practical political implications. There exists a patent granted by Edward III on February 10, 1344 permitting some Knights of the County of Lincoln to meet annually to hold jousts and indulge in other armed sports. The King, recalling that "the deeds of the ancients had exalted military glory and strengthened the throne" and also "that dissensions had often arisen from their not having employment," was pleased to permit the Knights to "meet peaceably without oppression to the populace in said parts or to engage in unlawful assemblies" for the practice of arms. By 1350 he had gathered a similar group of twenty-four Knights and the Prince of Wales around him at Windsor. Although these men were his advisers, his friends, and companions in arms, they were formed into a regular society, with a chapel of their own and a blue garter for their distinguishing badge. There is no absolute historical foundation for the old story that the order was founded because one day, when the Countess of Salisbury's garter broke and dropped to the ground, the King picked it up and, noticing the undertone of gossip among the assembled courtiers, promptly coined that immortal Norman French sentence, "Honi Soit Qui Mal y Pense." But on the other hand, there is no evidence that the story is pure fabrication, and it remains our only logical explanation for the motto that was embroidered on the blue Garter of the Knights of the new fraternity.

The Garter was the first example of the insignia of a British Order. The Knights were enjoined by the statutes of the Order to wear it daily. As Ashmole notes, the constant display of the insignia was important because it was worn by the members "as a sign of Brotherhood which from being constantly in sight might stimulate them to observe their oath of loyalty to the Sovereign and of devotion to virtue military as well as civil." Knights of the Garter followed the custom of wearing some part of their insignia as an article of daily apparel as late as the seventies of the last century. The Garter illustrated (Frontispiece) is 22½ inches long, of dark blue velvet decorated with gold embroidery and with the motto in letters of gold. The buckle and tabs are hallmarked. It is now in the possession of the Earl of Halifax K. G., former Viceroy of India, Foreign Minister and at present (1945) British Ambassador to the United States. Although this Garter is very plain, many Knights in the past have had theirs set with precious stones. Frequently, valuable and heavily jewelled Garters have been presented to foreign Sovereigns. King Charles I's Garter was set with 400 diamonds. Since it was the custom of the Knights to wear the Garter daily when knee breeches were popular, they often provided themselves with several additional Garters. Many exist today that are embroidered in plain gold or silver thread on light blue corded silk. The only other device that the original members wore was a blue cloak with an embroidered St. George's cross surrounded by a buckled garter on the left shoulder.

It was not until the reign of Henry VII that the most prominent part of the Garter insignia was instituted. During the second half of the fifteenth century and the early sixteenth century style decreed that gentlemen of quality should wear some form of heavy gold chain with their daily dress. When the famous Order of the Golden Fleece was founded by the Duke of Burgundy in 1469 a gold chain or "collar" was designed as the principal nisignia of the Order. Whether the King of England was moved to copy this part of the Fleece's insignia is not known, but it seems very probable that he was. The Earliest mention of the Garter collar (Plate I) is in a document describing the mission sent to invest the Emperor Maximilian with the insignia of the Order in 1503. When the Emperor was elected a Knight in 1489 no mention was made of the collar. It must have been added, then, between the years 1490 and 1502. According to the statutes it is composed of twenty-four heraldic Tudor roses enamelled red and white, each surrounded by a buckled garter and linked together with twenty-four "lover's knots" of gold, the whole weighing thirty ounces of twenty-two carat gold. In actual practice there seems to have been considerable variation in the weight of the collar. That belonging to Charles I was weighed by Cromwell's commissioners before melting and was found to be considerably overweight. Today the collars weigh 37 ounces, 6 pennyweights. The collars worn by Queen Victoria, Queen Mary and the present Queen appear from photographs to have been constructed on a much smaller scale than those of the knights and must therefore weigh much less. Unlike the other insignia, the collar cannot be jewelled or ornamented in any way.

The collar supports "The Great George," an enamelled gold equestrian figure of the Order's patron Saint slaying the dragon (Plate I). This figure is now one and three quarters inches in depth but has varied considerably in size and workmanship in the past. Queen Anne gave the Duke of Marlborough a magnificent George set in diamonds. This piece later passed into the hands of the Prince Regent who gave it to the first Duke of Wellington.

In the early days the Great George appears to have been surrounded by a Garter. A portrait of Queen Elizabeth's Minister, Lord Burghley, in the Garter Robes shows one in this form. As the result of changes in men's styles, by the middle of the sixteenth century the collar ceased to be generally worn. In 1519 the Statutes permitted the Knights "in time of war, sickness, long voyage, or other necessary occasions to wear the image of Saint George dependent to a little chain of gold or lace of silk". In 1521 the image was described as being surrounded by a Garter. This became known as the "Lesser George." During the reign of Charles I it was generally worn from a wide blue ribbon. For some unknown reason King Charles stopped wearing it around the neck and, instead, slung the ribbon over the left shoulder, the Lesser George, or Badge resting low under the right arm. The Badge has been worn in this way ever since. Today it rests on the right hip. Like the other insignia, the form of the Badge has varied over the centuries. The statutes decree that it shall be made of plain gold. The one illustrated (Plate II), belonging to the Earl of Halifax, is plain, and measures two and seven-eighths inches in depth. Many have been set with precious stones and have been considerably larger. In the days when the Badge was more frequently worn, the Knights had several made for themselves at their jewelers to suit their individual tastes. The Royal Family has a number of very fine Badges that are frequently displayed in photographs of some of the older members. Before leaving the Lesser George it should be pointed out that the four-inch blue ribbon from which it is suspended is a very important part of the insignia. In fact "The Blue Ribbon" is a common synonym for the Garter. The shade of blue has changed a number of times. The Stuarts wore one that was very light. The Hanoverian dynasty changed to one that was very dark. The late King George V changed the color again to what may be described as a very deep sky blue.

One of the most attractive pieces of the Garter insignia is the Star (Plate III). The Star is an outgrowth of the St. George's Cross and Garter worn on the robes of the original Knights. King Charles I surrounded his Cross and Garter with embroidered silver rays. In time this device was embroidered on the outer coat of the Knights. By 1800 the Knights had their Stars executed in silver, but they were still sewn on. In time the Star grew smaller in size and today it is pinned on. While the Stars of most of the British Orders are of standard make at the present time, the Stars of the Garter seldom are the same size or shape. The Star illustrated on Plate IV is the second that the Earl of Halifax has had. When it was given to him he returned the original piece to the Sovereign. This Star is very old and is not of the usual chipped silver construction that is so characteristic of the Stars of other Orders. The variation that is so typical of the Garter Star can be partially explained by the fact that all the insignia are returned on the death of the Knight. This has not always been the case, however. There were numerous instances in the sixteenth century where the Knights willed their collars to their heirs or to a friend. Eventually the Chancellor of the Order laid successful claim to the insignia, apparently for his own profit. In 1825 the Chancellor had to forfeit the insignia to the Crown but he was granted £100 for each set to reimburse him for his loss. Finally, in 1838, he was deprived of even this fee. Today the Collar, Great George, and Garter go to the Central Chancery, while the heir of the deceased Knight delivers the Star and Badge to the King. All the insignia are subsequently reissued. Considerable obscurity, at present, surrounds the insignia now worn by the Knights. It is not known how old the various pieces are, whether any record has been kept of the Knights who formerly wore each piece, just what degree of age and wear is necessary before a piece is worn out or what the incidence of loss is. The author suspects that considerable information could be made available on this aspect of the Order.

The Order of the Garter is remarkable in that its organization has been maintained for six hundred years without a break. It never died out to be revived with pretences of antiquity years later. It is as closely associated with the Monarchy as St. Edward's Crown itself.

In 1687 King James II decided to give the Kingdom of Scotland an Order that would be comparable to the Garter in England. He adopted the strange expedient of "reviving" a non-existent Order supposedly founded by a former King of Scotland in 787 and gave it the name of Scotland's national flower with St. Andrew for a patron Saint. Inasmuch as the original group of Knights were largely supporters of the Stuart cause, the Order suffered an eclipse after the Revolution of 1688. It was actually revived by Queen Anne in 1703. Lord Dartmouth summed the matter up as only an Englishman could. "It was revived in the reign of Queen Anne" he wrote, "with some new regulations, and they styled themselves Knights of the most ancient Order of St. Andrew, though nobody ever heard of a Knight of St. Andrew till the time of King James II. All the pretense for antiquity is some old pictures of the Kings of Scotland with medals of Saint Andrew hung with gold chains around their necks,—and everybody knows that gold chains and medals were worn formerly for ornaments by persons of quality and are still given to Ambassadors. But Charles II used to tell a story of a Scotchman that desired a grant for an old mill because he understood that they had some privileges and were more esteemed than the new."

Whatever the motives behind the pretense of antiquity the Order of the Thistle was soon held in high esteem. It is probably the most exclusive Order in Europe. From its foundation until 1821 the Knights numbered only twelve. In the latter year four extra Knights were added incident to the Coronation of George IV. In 1827 the number of members was fixed at sixteen where it remains today. The magnificent Chapel of the Order, in Saint Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh, is of modern origin and was finished just before the last War. One of the most interesting installations of Knights was held in July 1937 when Her Majesty the Queen was installed as the first Lady of the Order.

The Thistle has served its purpose well. It is a very much prized distinction in Scotland, where the little differences that distinguish the Scot from the Englishman are preserved with a fierce pride that would astonish the foreigner. In recent years the Order has been given to several gentlemen who, to paraphrase Lord Palmerston, are as distinguished for their deeds as for their ancestors. The motto of the Order is "Nemo Me Impune Lacessit" (Nobody attacks me with impunity).

The insignia of the Thistle were designed on lines similar to the Garter insignia. The gold collar, one and two-tenths inches in depth, is composed of sixteen thistles interlaced with four sprigs of rue enamelled in colors. Like other collars it is fastened to the deep green mantles of the Order with white ribbons. The original statutes of the Order provided that pendant to the Collar "is to hang the St. Andrew in gold, enamelled, with his gown green, and the surcoat of purple having before him the cross of his martyrdom enamelled white, or if of diamonds, consisting of the number of thirteen, just the cross and the feet of Saint Andrew resting on a ground of green." In February, 1714, it was further provided that "the Image of St. Andrew ... be made larger than it now is and have round it rays of gold going out from it making the form of a glory." Provision was made in 1687 to wear this "jewel" from a purple watered silk ribbon over the left shoulder tied under the right arm as the Garter ribbon was worn. Queen Anne changed the color of the ribbon to a rich dark green, and so it remains today. Whenever the jewel was not worn to the ribbon, it was to be replaced by an oval gold medal consisting of a figure of St. Andrew as prescribed for the jewel, but in plain gold, surrounded by a gold band bearing the motto of the Order. In practice, the jewel was seldom worn attached to anything but the collar. Queen Anne wore a very interesting Badge to the Garter ribbon. It had a Saint George and Garter on one side and the St. Andrew on the other. The Star of the Order (Plate V) consists of a Saint Andrew's Cross in silver with silver rays going out from the angles, charged in the center with a thistle of green on a field of gold, surrounded by a circle of green bearing the motto of the Order in gold.

A number of the collars and Badges now in possession of the Knights of the Thistle date back to the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Many of them represent some of the best workmanship of the early Scottish jewelers. There is a very fine jewelled medal of the Order with the Crown jewels in Edinburgh Castle that is worn by the Sovereign when he takes up residence in the Palace of Holyroodhouse. The Star illustrated (Plate V) is a magnificent specimen and is in the collection of the American Numismatic Society in New York City. The insignia of the Order are returnable to the King on the death of each Knight.

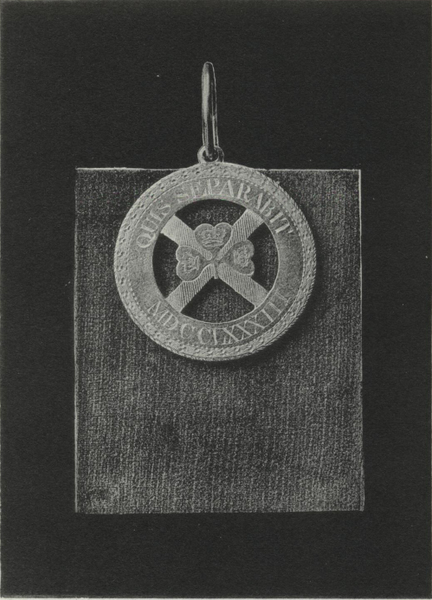

Following the precedent of Walpole, the Earl of Shelburne, Prime Minister in 1782, felt it necessary to conciliate the more powerful Irish Peers by finding honors and distinctions for them. The limited number of Knights in the Orders of the Garter, the Thistle and the Bath made it inconvenient for these Orders to be used for Lord Shelburne's purposes. The solution of the difficulty was to persuade the King to create a new Irish Order named for the patron Saint of that country. The Order of Saint Patrick, founded by George III in 1783 has filled the position of principal Order in Ireland. The Knights were limited to twenty-two, with the Viceroy acting as Grand Master. The collar of the Order (Plate VI), of pure gold, is composed of seven roses and six harps alternately, each tied together with a knot of gold, the roses being enamelled alternately white leaves within red and red leaves within white, and in the center an Imperial Crown surmounting a harp of gold from which hangs the Badge. The Badge is a large oval having in the center a three-petaled shamrock, or "trefoil," in green, on a red Saint Andrew's cross surrounded by a blue circlet bearing the motto of the Order, the whole surrounded by a wreath of green trefoils. There seems to have been great variation in the size, shape and enamelling of the St. Patrick's Badge. The Badge illustrated on Plate VII is in plain gold and was worn by one of the Knights founders of the order. While the usual Badge is oval, photographs of the Knights taken after 1850 show several circular specimens. That worn by the late Field Marshal Lord Wolseley was circular. When Lady Wolseley requested permission of the officials of the Order to present her husband's Howland Wood> Collar to the Royal United Services Museum along with the rest of his Orders and decorations, permission was refused. She had a copy of the collar made in gilt and it is, in normal times, on display with the magnificent Wolseley collection at the Museum. Lord Wolseley's circular Badge was much larger than the early specimen mentioned above. The Star of Howland Wood> (Plate VIII) is the usual eight-pointed star charged in the center with a representation of the Badge.

In 1831 King William IV caused the Irish Crown jewels to be used to make an unusual set of the insignia of Saint Patrick for the adornment of the Grand Master on special occasions. Each retiring Lord Lieutenant was required to hand the jewelled ornaments over to his successor. The State Insignia consisted of the following pieces: "A large Star of the Order of Saint Patrick composed of fine brilliants, having an emerald shamrock in the center, surrounded by the motto of the Order in diamonds on a blue enamelled ground; a large oval badge of the Order surmounted with the Crown, all composed of fine brilliants with an emerald shamrock on ruby cross; a gold Badge of the Order richly enamelled and set with emeralds and rubies."

The Order of Saint Patrick is in an anomalous position. The very motto, "Quis Separabit?" posed a question Englishmen were unwilling to recognize, and one which numerous Irishmen were all too willing to answer. Many members of the Order have been distinguished men. Yet many were men not too popular with their neighbors in Ireland because they represented the absentee landlord class. When the separation did come the Order lost its Chapel in St. Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin. In 1908 it had lost the State insignia of the Order in diamonds, which disappeared from Dublin Castle under mysterious circumstances and have not yet been found. The last Knight to be created, barring two members of the Royal Family, was the Duke of Abercorn in 1922. While the Order was complete as late as 1924, it seems about to lose all its members. There is no information about the Order's future now available.

The Orders of Merit comprise the group of decorations made available for services in the armed forces and in various administrative capacities throughout the Empire. Of these the prototype is "The Most Honourable Military Order of the Bath," an Order of Knighthood that stands second only to the Garter in the general esteem in which it is held. The name of the Order is actually centuries older than the Order itself, as we know it today. When the honor of Knighthood was conferred with special ceremonies by the Sovereign himself the candidate had to submit to many symbolic rituals. One of these was the taking of a bath as a symbol of purity and the washing away of sin. There are records of Knights of the Bath, but not Knights of an Order, being created as early as 1399. By the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries most of the ritual had been dispensed with, but certain Knights created at coronations and on other occasions were still denominated Knights of the Bath. Portraits of some of these Knights show them wearing an oval gold medal enamelled white and charged with three garlands or crowns of green. But it was not until 1725 that, under the stress of political necessity, the Order was actually created. The Prime Minister, Sir Robert Walpole, maintained his position by using the honors at his command to purchase political support of many of the great Peers, so wealthy in their own right that money meant little to them. Horace Walpole wrote that "The revival of the Order of the Bath was the measure of Sir Robert Walpole and was an artful bank of thirty-six ribbands to supply a fund of favors in lieu of places. He meant to stave off demands for Garters and intended that the Red should be a step to the Blue." The order was provided with a set of statutes that were more reminiscent of medievalism than of the cynical eighteenth century. Sir Harris Nicolas observed that "in 1725 King George I 'revived' as it was termed, the Order of the Bath, but little of the original institution except the most objectionable parts was retained, that is to say a name which was wholly inappropriate, a Motto and Ensigns that conveyed no obvious meaning and inculcated no moral or patriotic duty; and ceremonies so inconsistent with the feelings of the age that they were never intended to be performed." There is a great deal of truth in this judgment. But, like every other similar institution, the eventual value of the Order was measured not in terms of its founder's intentions but by the uses to which it was subsequently put. In fact the red ribbon of the Bath was not used as a step to the Blue. It presently became the principal military order in its own right.

The Napoleonic Wars ushered the Order into its most glorious period at the end of the eighteenth century. England entered the struggle in 1793. For the next twenty years the Royal Navy piled up one victory upon another. The men responsible for this record were, one by one, admitted to the Order. When Wellington's campaign got under way in Spain the army contributed its share to the ranks of the Order. One result of this extensive and successful series of military and naval operations was a great expansion in the number of members beyond the limits set by the statutes. By 1814 it became evident that there were not enough places in the Order to accept all those whose services merited it. The solution decided on by the authorities was a distinct break in the traditions that had begun with the Garter. On January 2, 1815, a Warrant was issued in which the Prince Regent declared that it was his desire to "commemorate the auspicious termination of the long and arduous contests in which this Empire has been engaged and of marking in an especial manner His gracious sense of the magnificent perseverence and devotion manifested by the officers of His Majesty's forces on sea and land." Therefore he thought it "fit to advance the splendor of the Order of the Bath and extend its limits to the end that those officers who have had the opportunities of signalizing themselves by eminent services during the late war might share the honors of the said Order and that their names may be delivered down to remote posterity accompanied by the marks of the distinction they had so nobly gained." The extension followed the pattern already set by the Order of St. Louis in France. The existing Knights of the Bath were called Knights Grand Cross (G.C.B.). There was a second and larger group called Knights Commanders (K.C.B.). Finally there was a third group numbering some seven hundred called Companions (C.B.) who were not Knights at all. Each group was provided with its own insignia that had only the remotest resemblance to the insignia that had previously been worn. Those few Knights who were civilians retained the old insignia. Provision was made for admission of a small number of distinguished civilians to the revised Order. They became "Civil Knights Grand Cross of the Most Honourable Military Order of the Bath."

It cannot be said that this complete change in the statutes of a highly respected Order was greeted with enthusiasm except, perhaps, by some of the new members who otherwise would have gone unrewarded. The older Knights felt that their hard won honors were cheapened by an influx of newcomers, many of whom had only the most shadowy claim to the distinction. The most distinguished living sailor, Sir John Jervis, Earl St. Vincent, violently objected to his new designation of G. C. B. and refused to wear the insignia except when in the presence of King George IV. There was agitation in Parliament. Members of the opposition pointed out that by the statutes the Knights were required to maintain a certain number of men at arms, "by which means the Crown might raise an armed band surreptitiously .... Whenever a nation was a military nation there ought to be a military order; but England is not a military nation." The objection was not merely the result of a post-war reaction against all things military. It was a fear as old as representative government in England. There was, however, little danger if only on the grounds of expense. Perhaps the most serious objection could be found in the fact that the new arrangement did not provide any means for the Prince Regent to recognize the achievements of most of the men his "gracious sense" indicated were worthy of distinction. The third class was limited to Majors in the Army and Post Captains in the Navy. There was no provision of any kind made for the thousands of officers and men in lower ranks, either within the Order or outside it.

It cannot be denied that the revision of the Order of the Bath placed that institution under a cloud for a time. Part of the difficulty lay in the fact that many important people had trouble in adjusting themselves to an award that tended to transcend class distinctions. The ultimate wisdom of the newly constituted Order was, however, soon recognized. In 1847 Queen Victoria was able to add a Civil Division of Knights Commanders and Companions without causing any great upheaval. Probably the greatest disability that the Order suffered under during the Queen's reign was the prosaic attitude adopted toward all honors. The impressive ceremonies at one time associated with the Garter, the Thistle and the Bath were allowed to lapse. Promotion in the Order was made more according to seniority and age than merit alone. Significantly Lord Wolseley refused a G. C. B. when it was first offered in 1882 because he feared that acceptance of the honor would damage his career. He felt that he was too young to be promoted in the Order over the heads of senior generals. This practice contrasted unfavorably with the customs followed in Russia and Austria in regard to the Orders of St. George and Maria Theresa. In the case of the Russian Order of St. George the first class was so sparingly granted that in 1914 no living Russian could wear it. However, in the nineteenth century with the multiplication of junior Orders, the Bath began to regain its former position in public estimation. It was left for the late King George V to revive the impressive ceremony of the Installation of the Knights in the renovated Henry VII's Chapel in Westminster Abbey. The attention which the King bestowed on the order was marked. There were few instances when he was seen in uniform not wearing its insignia. The Great War added new lustre. The London Times noted in 1920 that "Even in the late War, when honours lists were criticized for their length, admission to the Order of the Bath was charily granted and membership in its first class is still regarded as the fitting reward for the greatest victories and is highly prized as an honorary distinction by foreign rulers." After a checkered history the Order seems finally to have achieved a lasting and distinguished place in the British honors system.

By the time the Order of the Bath was founded, the insignia of all orders had become fairly well standardized. It was unusual for an Order to be possessed of three different types of badges as was the Garter. Normally there was one Badge, worn from the collar on occasions of ceremony, and from the ribbon of the Order on all others. The insignia of the Bath followed this tradition when it was designed in 1725. But the Badge instead of being designed as some form of a cross, as was most frequently the case in Europe, followed the distinctly English tradition already set by the Garter and the Thistle. The Badge was an oval pierced medal of varying size containing a sceptor between three imperial gold crowns with a rose, thistle and shamrock between, surrounded by a gold band on which the motto of the Order, "Tria Juncta in Uno" appeared in letters of burnished gold. This Badge was retained after 1815 as the Badge of the Civil Division (See Plates XV-XVII). The Star worn by the Knights between 1725 and 1815 was in the conventional form, having four greater and four lesser points, with three imperial crowns of gold in the center surrounded by the motto of the Order in gold letters on a crimson circlet (Plate IX). The collar, a chain of unusual length, is officially described as being made of gold, thirty ounces troy in weight, one and one-eighth inches in depth, composed of nine gold Imperial Crowns, eight gold roses and thistles issuing from a scepter enamelled in colors, tied with seventeen gold knots enamelled white (Plate X).

It was originally intended that the insignia of the new Knights Grand Cross in 1815 should be similar to those of the old Knights with the addition of a laurel wreath around the Badge and around the central device on the Star. But other counsels prevailed with altogether satisfactory results. The Badge of a Military Grand Cross is a gold Maltese Cross three and one-quarter inches square enamelled white, edged in gold, and tipped with small gold balls, and a gold lion "passant guardant," to use the heraldic term, in each of its four angles. In the center there is a device of crowns, scepter, rose, thistle and shamrock, surrounded by a crimson circlet bearing the motto, the whole encircled with a laurel wreath tied with a blue ribbon bearing the motto "Ich Dien." (Plate XI). It is worn over the right shoulder on a crimson sash, four inches in width, and rests on the left hip. The Badge of a Knight Commander is like the Grand Cross, but only two and one-eighth inches square. It is worn around the neck by a two inch crimson ribbon threaded through a heavy gold ring ornamented with oak leaves (Plate XII). This, under conditions of modern formal dress, is very awkward. At one time, however, when large heavy open collars and stocks were common, the Badge of a K. C. B. was not worn at the neck by a miniature ribbon as it is today, but low on the breast suspended from the investiture ribbon (Plate XIII). A Companion wears the same Badge one and three-quarter inches square from a one and one-half inch ribbon threaded through a plain gold ring (Plate XIV). The Badges for the Civil Knights Commanders and Companions (Plate XVII) are the same as those worn by the old Knights but smaller in size. The Badges of the Companions were not worn at the neck until 1917. From 1815 until that year they were worn, medal fashion, attached to the breast. It is common to see Companions' Badges today converted for neck wear.

There was variation in the Badge provided for in the Statutes. Members of the first class who were also Knights of the Garter were directed to wear their Badges suspended from an Imperial Crown. In fact none of the crowns were Imperial, but are Royal in form with the characteristic depressed arch. King George IV, the Duke of Wellington and the Marquess of Anglesey wore them this way, but the practice never became wide spread. King William IV, who regarded himself as Great Master of the Order, wore a badge of this kind. The Duke of Sussex, made Great Master by Queen Victoria, wore a Civil Badge suspended from a crown. In time it became the custom for the Sovereign of the Order and the Great Master to wear the crowned Badges but no others. A portrait of the Prince Consort by Winterhalter shows a large crowned Badge and collar thrown over the robes of the Order in the background. But in modern times King Edward VII, King George V, and the late Duke of Connaught wore a small crowned Badge suspended from the neck. King George V seems to have had at least two such insignia. It should be noted that Lords Roberts and Kitchener, who according to the original statutes could have worn this unique form of Badge, did not do so. To the best of the author's knowledge, the present Earl of Derby K. G., a Civil G. C. B., has not done so either. Without access to complete files of the numerous minor changes in the statutes, it seems likely that the custom was first allowed to lapse until finally the crown was dropped. Nothing is known at present of the history of the crowned Badges now in the possession of the Royal Family.

A completely new set of Stars was also designed for the Order in 1815. The Star of the Civil Knights remained substantially the same. But the Military Knights' Star was charged with a device similar to the Badge except that the cross was entirely of gold and the lions were eliminated (Plate XVIII). Knights Commanders were given a Star of an entirely new and original shape composed of four rays of silver in the form of a cross, with four small rays between and ends squared (Plate XIX). The Military K. C. B.'s wore the Star charged in the center with the device as for the Military G. C. B. but without the gold cross, while the Civil K. C. B.'s central device was exactly the same as that of the Civil G. C. B.

Throughout the eighteenth century it was customary for Knights of an Order to have as many Stars as they needed embroidered to their coats or uniforms. They were apparently not invested with a metallic Star at all. If a Knight wished to have a Star of other materials than silver or gold thread it was generally executed in precious stones or paste. All of Lord Nelson's existing Stars of the Bath are embroidered on his uniforms. Toward the end of the century, however, metallic Stars began to appear. The Star of the K. B. in Plate IX is pierced at the tips of the rays, and each ray hinged, to facilitate sewing. This is also true of Sir John Moore's silver K. B. Star in a collection of the United Services Museum. As a result, one finds early Stars of the British Orders in all sizes and shapes. In spite of the change of fashion, however, after 1815 the Knights of the Bath began to have Stars in tinsel given them when they were invested (Plate XX). Whether these were worn very much is doubtful because they were rather poorly made. Sir William Codrington in describing an Investiture of the Bath in the Crimea to Lord Panmure, the Secretary of State at War, wrote "We had no velvet cushions, but we had a scarlet cloth, one whose everyday occupation is more undignified than carrying the insignia of the Bath. The French, I am glad to see had their real stars given them; it looked a little awkward to see our own officers getting the spangled affair at the same time put into their own hands. We made the best of it, though I must say it looked like a little economy for a great nation at the time." How long this form of economy lasted it is impossible, in the absence of access to official records, to say with accuracy. Inspection of numerous photographs of G. C. B.'s and K. C. B.'s indicates that the change may have come about 1870. After that year, the Stars became standardized in size and in general appearance. The Stars on Plates XXI, XXII show how great a variation from the standard could result. The former is the official issue, while the latter is of private manufacture. There are only two Stars of the Bath that are definitely known to have been set with diamonds. One, the Star of a K. C. B., was given to Sir John Moore by his Staff and is now in the Royal United Services Museum in London. The other was in the possession of the late Viscount Esher, G. C. B. It was sold shortly before the present War, and both its history and present whereabouts are unknown.

The insignia of the Bath are described as being made of gold. This has not been true since the end of Queen Victoria's reign. The Badges and collars are now manufactured in heavy silver gilt. The Badge of the Civil G. C. B. illustrated on Plate XV is in gilt and is hallmarked 1918. The civil Badge illustrated on Plate XVI is at present in the possession of the Earl of Athlone K. G., G. C. B. The Military G. C. B. in Plates XXIII-XXV, presented to a distinguished American military figure by the late King George V in 1918, is of gilt, and this is also true of the Badges of Admiral of the Fleet Earl Jellicoe and Field Marshal Viscount Allenby. Although according to British law articles of silver and gold should be hallmarked, some insignia bear the required hallmark but an equally large proportion do not. Neither of the insignia mentioned above has any hallmark or maker's identification symbol.

Of the insignia of the Bath only the Collar and Badge attached are returned to the Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood. The Investment Badges and Stars may be retained by the relatives of the deceased Knights.

Among the most important strategic and colonial possessions acquired by Great Britain as a result of the Napoleonic Wars were the Ionian Islands and the Island of Malta in the Mediterranean. Political necessities made it seem advisable to create an Order for the reward of those natives of the Islands who showed their loyalty to the Crown. In 1818 the Order of St. Michael and St. George was established for this purpose. It was to consist of eight Knights Grand Cross (G. C. M. G.) twelve Knights Commanders (K. C. M. G.) and twenty-four Companions (C. M. G.), called Cavallieri when the members were Maltese. The Governor and Commander in Chief of the Islands was ex-officio Grand Master of the Order and the Commander in Chief in the Mediterranean was an ex-officio Grand Cross. The Order was open to other Englishmen who rendered service in the Mediterranean area. A good deal of comment was caused at the time by the peculiar limitations of the Order. By 1840, however, the use of the Order had expanded enough so that Sir Harris Nicholas, the Chancellor, felt that perhaps it would develop into an Order of Civil Merit in England. While his expectations were partially disappointed in this respect, the Order was greatly expanded during Queen Victoria's Reign in the numbers of its members and the purpose it had to serve. It became the principal award for services in connection with foreign affairs and the fast expanding Empire. It is customary, for example, for all newly appointed Governors General of the Dominions to receive the Grand Cross of the Order. During the Great War it served as a kind of junior Order of the Bath and as such was awarded to many members of the armed forces of Britain and her Allies.

The Chapel of the Order is in St. Paul's Cathedral, London. In normal times the annual services of installation are held there, on St. George's Day, April 23.

The insignia of St. Michael and St. George are the Collar, Badge and Star (See Plate X). The collar is described as being made of gold composed alternately of crowned lions of England, white Maltese crosses, and the cyphers S. M. and S. G. linked together with short, square linked gold chains. In the center there is an Imperial Crown over twowinged lions, each holding a book and seven arrows in his fore-paw, from which is suspended the Badge. The Badge is a seven-limbed cross in white enamel beneath a gold Imperial Crown. In the center, on one side, there is a lively representation of St. Michael assaulting the devil, on the other, one of St. George administering the coup de grace to an expiring dragon, each surrounded by a blue circlet bearing the motto of the Order, "Auspicium Melioris Aevi" in letters of gold. (Plate XXVI, XXVII). When not attached to the Collar, the Badge is worn to a Saxon blue sash four inches in width with a central scarlet stripe over the right shoulder resting on the left hip. The Star of the Order is composed of seven chipped silver rays with a fine ray of gold between, each mounted with a red cross of St. George. The center piece is a representation of St. Michael similar to that on the Badge and surrounded with a circlet containing the motto of the Order. The Knight Commander's Star is composed of four rays of silver with the limbs of a silver cross between them (Plate XXVIII). The center device is similar to that of the Star of the Grand Cross. Knights Commanders and Companions wear their Badges around the neck. The Badge of the Companion was formerly worn on the breast like the C. B. The Badge illustrated on Plate XXVI is that of the Grand Master of the Order at present worn by the Earl of Athlone K. G. It is of gold with the crowned cypher of St. Michael and St. George between the angles of each limb of the cross.

Insignia of this Order made at different stages of its existence are very hard to discover in collections or museums for study. The United Services has a very interesting Star worn by Admiral Sir Graham Moore, one of the original Knights, when he was Commander in Chief in the Mediterranean. It is boldly executed and the rays are smooth silver instead of the conventional cut silver. There seems to have been considerable variation in the over all size of the Badges and Stars. The K. C. M. G. Badge illustrated (Plate XXVII) is ca. 1900 and measures 2 7/8 inches from point to point on the cross or 3 15/16 inches from the top of the crown to the lowest point of the cross, while the Star measures 3 3/16 inches. Early in the reign of King George V, however, the insignia were made much smaller and consequently more pleasing in appearance. There is a K. C. M. G. pair in the collection of the American Numismatic Society which measures 3 1/2 × 2 13/32 inches for the badge and 2 31/32 inches for the Star. Like the insignia of the Bath the insignia of this Order is now made in silver gilt for all classes. None of it has to be returned on the decease of a Knight.

The Great War saw a total mobilization of British manpower and resources on a hitherto unprecedented scale. So many different varieties of services were being rendered that the existing Orders were in danger of being swamped if the demands made on them were granted. The King was faced with the same problem that the Prince Regent had been in 1814, but this time it was urgent before the successful conclusion of hostilities. The solution was not sought in an attempt to adapt one of the existing Orders to meet the new situation. An entirely new Order was established to commemorate the national and Imperial effort inspired by the War and to meet new needs which it seemed likely would be felt after the War was over.

The Order of the British Empire, founded on June 4, 1917, was marked by one unique feature. It made provision for the admittance of women to its ranks. Following the example previously set by the Royal Victorian Order, there were five classes established — Knights and Dames Grand Cross (G. B. E.), Knights and Dames Commanders (K. B. E. and D. B. E.), Commanders (C. B. E.), Officers (O. B. E.) and Members (M. B. E.). In 1918 a Military Division of the Order was established to be conferred on members of the British and Imperial forces for services which did not qualify them for one of the senior Orders but which were nonetheless of great value to the war effort. At first there was no specific limit put on the numbers of each class. By 1920 between seven and eight thousand persons had received the Order and the London Times thundered against it, advocating that either the Order be closed or "that an attempt be made to define more closely the nature and quality of the service for which it is to be conferred." The Order suffered from the same growing pains as the Bath. But it grew to maturity amazingly quickly. Although it is the newest of all British orders it has found a place that probably none of the others could have filled success- fully. The British Empire is used to recognize the contributions of small people throughout the Commonwealth in every conceivable form of activity. The O. B. E. sent to a school teacher or nurse in some remote outpost in Canada or Africa has probably brought as much satisfaction as any Blue Ribbon bestowed with all the rich ceremony and restrained pomp of which the British Crown is such a recognized master. The Badge of the Order is a cross patee in silver gilt enamelled pearl grey and suspended from a gilt Imperial Crown. In the center there are conjoint crowned busts of their Majesties King George V and Queen Mary surrounded by an enamelled crimson circlet bearing the motto of the Order, "For God and the Empire." It is worn by Knights and Dames Grand Cross over the right shoulder resting on the left hip from a rose pink sash edged with pearl grey. Knights Commanders wear a smaller Cross at the neck from a similarly colored ribbon while Dames wear theirs from a bow of ribbon on the left side below the shoulder. The Badge for Commanders is the same as for Knights and Dames. The distinction lies in the Commanders not wearing a Star. Officers and members wear a smaller Badge of the same design as the higher ranks in the Order but of silver gilt and frosted silver, respectively, without any enamel. It is worn on the breast, medal fashion, by men and from a bow by women on the left side below the shoulder.

The Star of the G. B. E. is of chipped silver with eight principal points surmounted with the same central device found on the Badge. That worn by Dames is slightly smaller than the Knights'. The K. B. E. Star is smaller, of a diamond shape, with four principal and four lesser points with the same central device found on the Grand Cross Star. The Collar of the Order was established some time in the middle 1920's. It is composed of six medallions of the Royal Arms and six medallions of the cypher of King George V linked together with cables. In the center is the Imperial Crown between two sea lions, from which is suspended the Grand Cross of the Order. The Collar is returnable on the decease of the Knight or upon receiving the first class of a higher Order. This design for the insignia was established for the Order in 1937 to commemorate the reign of King George V and Queen Mary. Between 1917 and 1937 the Badge of the Order was the same as described above except that in the center, surrounded by the crimson circlet and motto there was a seated figure of Britannia very closely resembling that on the bronze penny (Plate XXIX-XXXI). The ribbon of the Order was a dull purple with a narrow scarlet stripe added in the center for the military division. There never has been a difference in design between the insignia of the Civil and Military divisions. Today the latter is distinguished by the addition to the ribbon of a narrow central stripe in pearl grey. The Stars worn for the first twenty years were of the same design with the Britannia centerpiece but of plain fluted silver (Plate XXXII).

The statutes of the British Empire were the first to describe the insignia as being made of silver gilt. While the Collar has to be returned as noted above, there is the provision that members of the Order do not have to return their insignia on promotion to a higher class if it was awarded for services in the Great War. There have been two medals established with the Order that will be discussed in their proper place under decorations of valor.

The Order is still too new for any pertinent information about the insignia to have come to light. Nothing is yet known about the original design of the insignia or the reasons which led to the improvement in design in 1937. There are no variations in size and general construction or other distinctions that have come to the author's notice.

Before the creation of the Order of the British Empire there was no convenient means of rewarding the efforts of many lesser members of the Civil Service in administrative and clerical posts throughout the Empire. King Edward established the Imperial Service Order (I. S. O.) in 1902 to fill this need. Early in the reign of King George V the Order was extended to include women and the application of the Order was considerably broadened. Today it is limited to seven hundred Companions divided between the Home, Indian and Colonial Civil Services. Twenty-five years' service is required before an individual is normally qualified for admission to the Order, although this is reduced to twenty years for service in India and sixteen years in unhealthy hot countries. In outstanding instances the Order can be bestowed before the recipients have satisfied the above time limits. There is also a medal given to those not eligible for the award of the Order.

The Badge of the Order is a silver eight-pointed Star with burnished rays. In the center there is a gold circular plaque bearing the Royal cypher in blue enamel surrounded by the motto "For Faithful Service" and surmounted by a large Imperial Crown enamelled in the proper colors and covering the upper rays of the star (Plate XXXIII). The ribbon is red, blue and red in equal stripes. The Badge for ladies consists of the plaque as above but it is surrounded by a silver laurel wreath. This Badge is worn from a bow on the left shoulder. The first medals of the Order were of the same design as the Badges but were executed in silver and bronze. Latterly this medal has been issued in silver and is circular in form, the obverse bearing the Sovereign's head while the reverse has the name of the recipient engraved thereon.

The Venerable Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem in the British Realm is in many respects an extraordinarily interesting institution. The Order has very little resemblance to any of the other British Orders, either in its origins or present-day functions. Originally the Knights of St. John were a crusading organization founded in the eleventh century whose efforts were directed toward preserving the holy places in Palestine and relieving Crusaders. In succeeding centuries the Order became a powerful military organization with branches throughout Europe. The headquarters of the Order was first on the Island of Rhodes, and finally on Malta from which place it was driven out by Napoleon. The English branch was chartered by Queen Victoria in 1888. The Order renders services of immense value today. It supports the British Ophthalmic Hospital in Jerusalem and the work of the St. John's Ambulance Association and Brigade. The latter organization, for example, provides for: "(1) The dissemination of instruction in first aid, home nursing and hygiene, (2) The deposit in convenient places of stretchers, (3) The development of ambulance corps for the transport of the sick and wounded." Distinguished persons are admitted to the Order as well as individuals who do good work in the service of the Order. All admissions are sanctioned by the Sovereign after recommendation by the Chapter General and approval by the Grand Prior.

The insignia of the Knights of St. John adhere to the rigid simplicity that marked the Medieval institution. The Badge is a true Maltese cross enamelled white with lions and unicorns passant gardant alternately in the angles. The Star takes the form of a Maltese Cross enamelled white without any embellishments in the angles (Plate XXXIV). The size of the insignia varies with each of the five classes of the Order. Bailiffs and Dames Grand Cross wear the Badge in gold, three and one-quarter inches in diameter, from a black watered silk ribbon over the right shoulder resting on the left hip. The Star, three and five-eighths inches in diameter is worn on the right hip. Knights and Dames of Justice wear a smaller badge in gold around the neck and on the left shoulder respectively. Their Star is gold. Knights and Dames of Grace wear similar insignia but set in silver instead of gold. The classes of Knights of Justice and of Grace are for all practical purposes merged today, but the Knights and Dames of Justice still have certain privileges and are required to have certain genealogical qualifications. The Order is aristocratic in its origins and at one time members had to have as many as sixteen quarterings on their coats of arms. "The term ‘Knights of Justice' originally meant Knights who were noble by birth, while ‘Knights of Grace' were those of non-noble family who were admitted to the Order for their attainments." Chaplains wear the same Badge as the Knights of Justice, slightly smaller, and do not wear the Star. Commanders wear the Badge of the Knights of Grace in the same manner. Officers wear a still smaller Badge on the left breast while Serving Brothers and Sisters have a circular medal bearing the Cross of St. John in silver on a black enamel background.