For Alexander's chief Macedonian silver mint I use here when necessary the traditional name of Amphipolis. This name is used with great reluctance, for I have no confidence that this city, rather than Pella or perhaps Aegae or Philippi, was the source of this enormous silver output. With no specific evidence supporting the claim of any other city, however, it seems preferable at least for the moment to retain the usual attribution to Amphipolis–but with no assurance that the coinage was in truth struck there. A second Macedonian silver mint, usually referred to as Pella, is treated here only rarely and peripherally. This study concerns itself only with the chief mint.

The Alexander tetradrachms' pattern, established long ago by Edward T. Newell,1 is of a number of successive groups, each of which includes from three to twelve different issues, i.e., coins with differing reverse markings. Within each group there is heavy obverse linkage among issues. Not every die is known in multiple issues, but with almost no exceptions every issue is obverse linked with at least one, and usually more than one, other issue in its group.2

Table 1 lists the groups and their constituent issues. Groups A through K are listed by Newell's letters as he published them in the Demanhur hoard.3 The next group, not present in that deposit, I have termed L. Groups after L are not included in this study.

The groups are listed in Newell's order, with the single exception that the minute group K is placed before J. Justification for this minor shift, as well as for its continued attribution to our mint, is given below.4 Within each group the issues are listed in the order given in Alexander, Martin Price's recently published monumental compendium of Alexander issues,5 although within each group any order is meaningless, as die linkage patterns show that the issues within each group must all have been struck more or less simultaneously.

Table 1 is organized by inscriptions and groups with the number of coins studied given for each group. The first column in the table gives Newell's group letters, joined by issue numbers (repeating for each group) assigned by the present author. Hesitant as I have been to introduce a new set of numbers into this subject, I have been convinced to do so by the unsatisfactory choices available for describing these issues, which so often form major components of hoards and provide the basis for dating those hoards. Müller issue numbers are incomplete and their order virtually meaningless. Alexander's issue numbers and Demanhur hoard coin numbers give only a rough indication of where in this vast Macedonian coinage the individual issues fall. A system which indicates the group (more important than the issue in any case) in addition to the specific issue should be far more descriptive than one which identifies only the issue and does not always accurately place that issue. Thus B8, E2, and G3, for example, provide more readily useful information than Demanhur's 247, 716, and 1,168, or Alexander's 32, 78, and 110.

The table's second column describes each issue's marking or markings (the primary marking preceding any secondary one, regardless of their positions on the coins). A bold P indicates that issues of Philip II's types are known with the same markings. These Philips are probably posthumous in the case of those similar to the Alexanders of group A. Those parallel to the later issues, from group I on, are decidedly so.6

The third column gives the plate numbers of examples of each issue. The fourth and fifth give the issue numbers in Alexander 7 and the initial Demanhur hoard coin numbers. Issues illustrated in Alexander are marked with an asterisk, and those with whose descriptions I differ are placed where I believe they belong but in parentheses. Finally, as an indication of their relative abundance or rarity, the numbers of examples studied from each issue are given. The numbers of obverse dies located and the estimated totals used, better indications of the original size of the groups, are given in Table 2.

The tetradrachms' types are

Obv.: Beardless head of Heracles r., wearing lion's skin headdress.

Rev.: AΛEΞANΔΡΟΥ (or BAΣIΛEΩΣ AΛEΞANΔΡΟΥ in groups G, H, I, K, and J). Zeus seated l., holding scepter and eagle.

| Issue | Markings | Plate | Alexander Issue | Initial Demanhur Coin No. | Examples Found | |

| AΛEΞANΔΡΟΥ | ||||||

| Group A, 250 coins | ||||||

| A1 | P | Prow | 1 | 1, 4* | 1 | 82 |

| 2 | ||||||

| A2 | P | Stern | 3 | 5* | 56 | 56 |

| A3 | P | Double heads | 4 | 6* | 91 | 65 |

| A4 | Fulmen | 5 | 8*, 9* | 132 | 31 | |

| 6 | ||||||

| A5 | P? | Rudder | 7 | 10*, 11* | 151 | 16 |

| Group B, 212 coins | ||||||

| B1 | Cantharus | 9 | 12* | 254 | 20 | |

| B2 | Amphora | 10 | 13* | 162 | 48 | |

| B3 | Wreath | 11 | 14* | 229 | 16 | |

| B4 | Stylis | 12 | 20* | 240 | 6 | |

| B5 | Attic helmet | 13 | 21*, 22* | 243 | 11 | |

| 14 | ||||||

| B6 | Ivy leaf | 15 | 23* | 266 | 55 | |

| B7 | Grapes | 16 | 29* | 198 | 48 | |

| 17 | ||||||

| B8 | Caduceus (also in E)a | 18 | 32* | 247 | 8 | |

| Group C, 87 coins | ||||||

| C1 | Filleted caduceus | 19 | 36* | 332 | 10 | |

| C2 | Quiver | 20 | 38* | 302 | 24 | |

| C3 | Grain ear | 21 | 39, 39A | 317 | 10 | |

| 23 | ||||||

| C4 | Trident head | 23 | 43* | 327 | 3 | |

| C5 | Pegasus forepart | 24 | 44* | 340 | 27 | |

| C6 | Bow | 25 | 48* | 361 | 13 | |

| Group D, 216 coins | ||||||

| D1 | Eagle head | 26 | 51* | 373 | 32 | |

| D2 | Macedonian shield | 27 | 57* | 395 | 38 | |

| 28 | ||||||

| D3 | Club | 29 | 58* | 422 | 9 | |

| D4 | Horse head | 30 | 59* | 490 | 27 | |

| D5 | Star | 31 | 61* | 501 | 16 | |

| D6 | Filleted caduceus M | 32 | 65 | 426 | 1 | |

| D7 | Caduceus

|

33 | 66* | 472 | 12 | |

| D8 | Caduceus

|

34 | 67* | 481 | 10 | |

| 35 | ||||||

| D9 | Club

|

36 | 70* | 427 | 29 | |

| D10 | Club

|

37 | 71* | 455 | 20 |

| Issue | Markings | Plate | Alexander Issue | Initial Demanhur coin No. | Examples Found | |

| D11 | Dolphin | 38 | 73* | 509 | 15 | |

| D12 | Aplustre | 39 | 75* | 514 | 7 | |

| Group E, 605 coins | ||||||

| E1 | Roseb | 40 | 76* | 520 | 3 | |

| E2 | Herm | 41 | 78* | 716 | 124 | |

| E3 | Cock | 42 | 79* | 792 | 174 | |

| E4 |

|

43 | 83* | 536 | 75 | |

| E5 |

|

44 | 84* | 529 | 12 | |

| E6 | Pentagram | 45 | 87* | 521 | 13 | |

| E7 | Crescent | 46 | 89* | 579 | 54 | |

| E8 | Bucranium | 47 | 93* | 656 | 92 | |

| 48 | ||||||

| E9 | Caduceus (also in B)c | 49 | 99* | 614 | 58 | |

| Group F, 224 coins | ||||||

| F1 | Scallop shell | 50 | 102* | — | 2 | |

| F2 | Star in circle | 51 | 103* | 895 | 20 | |

| F3 | Cornucopia | 52 | 104* | 909 | 76 | |

| 53 | ||||||

| F4 | Athena Promachus | 54 | 105* | 967 | 85 | |

| F5 | Bow and quiver | 55 | 106* | 1014 | 41 | |

| 56 | ||||||

| AΛEΞANΔΡΟΥ BAΣIΛEΩΣ or BAΣIΛEΩΣ AΛEΞANΔΡΟΥ | ||||||

| Group G, 287 coins | ||||||

| G1 | Cornucopia | 57 | 108* | 1043 | 111 | |

| G2 | Athena Promachus | 58 | 109* | 1100 | 107 | |

| G3 | Bow and quiver | 59 | 110* | 1168 | 69 | |

| BAΣIΛEΩΣ AΛEΞANΔΡΟ Υ | ||||||

| Group H, 455 coins | ||||||

| H1 | Antlerd | 60 | 111* | 1210 | 84 | |

| H2 | Phrygian cap | 61 | 112* | 1344 | 181 | |

| H3 | Macedonian helmet | 62 | 113* | 1251 | 142 | |

| H4 | Trident head | 63 | 114* | 1456 | 3 | |

| H5 | Tripod | 64 | 115* | 1458 | 45 | |

| Group I, 177 coins | ||||||

| 11 | P? |

, ,  etce etce

|

65 | (118*), | 1471 | 40 |

| (119*) |

| Issue | Markings | Plate | Alexander Issue | Initial Demanhur coin No. | Examples Found | |

| 66 | ||||||

| 12 |

|

67 | 120* | 1488 | 63 | |

| 68 | ||||||

| 13 |

|

69 | 121* | .1512 | 74 | |

| 70 | ||||||

| Group K,f 18 coins | ||||||

| K1 | Λ | 71 | – | – | 1 | |

| K2 | P | Λ,  (or (or

|

72 | 421*, 425, 426 | 1582 | 10 |

| 73 | ||||||

| 74 | ||||||

| 75 | ||||||

| K3 | P | Λ

|

76 | 422 | – | 2 |

| K4 | ΛT | 77 | 423 | – | 1 | |

| K5 | Λ

|

78 | 424 | – | 1 | |

| K6 | P | Λ

|

79 | 424A | – | 1 |

| K7 |

|

80 | 427 | – | 2 | |

| Group J, 147 coins | ||||||

| J1 | Grain ear | 81 | 116* | 1538 | 3 | |

| J2 | Crescent | 82 | 117A | – | 3 | |

| J3 | Laurel branch | 83 | 117 | 1563 | 2 | |

| J4 | P |

grain ear grain ear

|

84 | 122* | 1541 | 46 |

| 85 | ||||||

| J5 | P |

crescent crescent

|

86 | 123* | 1551 | 34 |

| 87 | ||||||

| J6 |

laurel branch laurel branch

|

88 | 124*89 | 1564 | 59 | |

| 89 | ||||||

| AΛEΞANΔΡΟΥ | ||||||

| Group L, 271 coins | ||||||

| LI | P |

forked branch forked branch

|

90 | (126*), 140 | – | 8 |

| L2 |

filleted club filleted club

|

91 | (127*), 128 | – | 5 | |

| L3 | P |

aplustre aplustre

|

92 | 129*, (135) | – | 91 |

| 93 | ||||||

| 94 | ||||||

| L4 |

grain ear grain ear

|

95 | 96 | 130* | 14 | |

| 97 | ||||||

| L5 | P |

crescent crescent

|

98 | 131* | – | 12 |

| L6 | P |

wreath wreath

|

99 | 132* | – | 52 |

| L7 | P |

dolphin dolphin

|

100 | 133* | – | 69 |

| L8 | P |

profile shield profile shield

|

101 | 136*, (137) | – | 12 |

| L9 |

fulmen fulmen

|

102 | 138 | – | 2 | |

| L10 | P |

axe axe

|

103 | 139 | – | 6 |

Succeeding groups, all inscribed AΛEΞANΔΡΟΥ and struck before ca. 295 B.C.,8 were

not subjected to a die study. They include:

P Λ or

over bucranium, and varying additional marking;

over bucranium, and varying additional marking;

P

over race torch, and varying additional marking;

over race torch, and varying additional marking;

P Λ over race torch, and varying additional marking or markings;

P fulmen over I, and varying additional marking; and star, obelisk, and X

(varying positions), or star over obelisk, and varying additional marking or markings.

As has been noted, within each group it is clear that all issues must have been struck more or less simultaneously, and the die linkage is so complex that it is impossible to place the issues in any linear chronological order. Three typical clusters of coins are diagrammed in Figures 1–3. They come from group H, but similar clusters and die linkage are found in almost every group (e.g., note in Table 1 the obverse die used for six issues in group D). The clusters presented below are simplified. Another antler obverse, for instance, sharing a reverse die with the first coin listed but not linked by its obverse to any other symbol, is omitted. Brackets to the left and horizontal lines indicate obverse die identities, and brackets to the right, reverse die identies. All coins are illustrated on Plates 5–6.

Alexander Tetradrachms: Obverse Die Links within Group H

| H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H5 |

| Anter | Phrygian Cap | Macedonian Helmet | Trident | Tripod |

A further confirmation of the contemporaneity of issues within groups is provided by the obverse links between groups described in Chapter 3. Issues struck in linear sequence would tend to have one issue in a given group linked to one issue in another. Instead, especially among groups after A and B, the obverse dies forming links between groups were often employed for a great number of issues.

| a | |

| b |

This small issue E1 is catalogued where Newell placed it in

Demanhur. It is not clear whether he eventually knew the die link shown above (40

and 44), but in Reattrib. (p. 10, issue XXVII), he commented on the one specimen he knew

from the issue that the coin's "obverse resembles the obverses of previous coins [of group D], while the reverse is almost

identical in

style and workmanship with the following [group E]." Once again, Newell's remarkable sense of style is clear,

as there is now known a second obverse die in the issue, which was used also in group D: see Chapter 3, link 17. E1 might

thus belong to

either D or E, but is here left in its traditional place. In either case, groups D and E are joined by one known obverse die.

|

| c |

See issue B8 with note a, above.

|

| d |

"Antler," the accepted name for this symbol, is unsatisfactory. It often looks more like a ragged branch.

|

| e |

See p. 27, commentary on Alexander issues 118–19.

|

| f |

For discussion of the disputed placement and even attribution of group K, see pp. 49–50.

|

| 1 |

Reattrib., pp. 5–23, and

Demanhur

, pp. 26–32, 65–66, finalizing the classification presented in Reattrib.

|

| 2 |

The exceptions are very small issues in groups K and L (K3, K5, K6, L2, L9), whose markings make their group placements certain.

|

| 3 |

See above, n. 1.

|

| 4 |

See pp.49–50.

|

| 5 |

Alexander, pp. 89–103, with the addition of some issues from p. 132.

|

| 6 |

See Chapters 4–6 for these late posthumous Philip reissues.

|

| 7 |

Alexander, pp. 89–103 and 132.

|

| 8 |

For these issues, see "Tetradrachms Amphipolis." Ehrhardt here also notes the posthumous Philip II issues which were struck in parallel with the Alexanders

through those with fulmen over I. These Philip issues form Amphipolis group IV in

Philippe

. The final group, with star, obelisk, and X, may not belong to our mint. Price in Alexander (pp. 139–40) tentatively prefers an older attribution to Uranopolis, but an Amphipolis

origin is most recently strongly defended by Thompson in "Cavalla," pp. 40–44.

|

Newell's coin numbers, as they are found on the ANS's coin boxes, cast cards, and photo file cards, are provisional working numbers only, and they encompass many numbers for which there seem to be no examples. When I finally consulted Newell's notebook (described in the introduction), no examples for the missing numbers appeared there either. Clearly he sometimes left runs of numbers unused available to be assigned to subsequently acquired specimens, and consequently his die numbers cannot be taken as cumulative and do not show the total numbers of obverse dies in the various groups. For example, in group I, his die numbers run from 660 through 723, for a total of 64 numbers. Three pairs of those numbers, however, were given to identical dies, for a loss of 3. Similarly, there are 13 numbers with no examples known (not in the trays and not mentioned in his notebooks), and I have found 8 additional dies. Instead of Newell's apparent total of 64 dies for group I, there seem to be only 56. Similar situations obtain in each group.

Table 2 shows the numbers of coins studied in the various groups and the numbers of obverse dies identified in each group. "Coins" include ANS coins (approximately half of all located), casts, illustrations in the ANS's photo file, or examples pictured in readily available publications. The number of obverse dies given for each group is reduced by 0.5 for each die shared with another group. The final column, the number of estimated dies, is the number arrived at by the useful equations published by G. F. Carter.9

Group E (605 coins, 193 dies known and 241 estimated) is clearly the largest group, but, if as seems probable, F and G should be combined into one group, then that resulting group would be a close rival (511 coins, 162.5 dies known and 203 estimated). Group L was also very large.

| Group | Coins | Obverse Dies | Coin/Die Ratios | Estimated Obv. Dies |

| A | 250 | 72.5 | 3.45 | 88 |

| B | 212 | 43.5 | 4.64 | 49 |

| C | 87 | 16 | 5.50 | 18 |

| D | 216 | 62.5 | 3.46 | 76 |

| E | 605 | 193 | 3.13 | 241 |

| F | 224 | 71 | 3.15 | 89 |

| G | 287 | 91.5 | 3.14 | 114 |

| H | 455 | 97 | 4.69 | 109 |

| I | 177 | 56 | 3.14 | 70 |

| K | 18 | 7 | 2.57 | 10 |

| J | 147 | 30 | 4.90 | 33 |

| Totals A-K/J | 2,678 | 740 | 3.62 | 885 |

| L | 271 | 139 | 1.95 | 232 |

| Totals | 2,949 | 879 | 3.34 | 1,075 |

| 9 |

"A Simplified Method for Calculating the Original Number of Dies from Die Link Statistics," ANSMN 28 (1983),

(1983), pp. 195-206, at p. 202. The total estimated dies are calculated from the total numbers of coins and dies, not by the

addition of

the estimated dies in the various groups.

|

| Alexander Issue | Troxell Issue | |

| 1, 4 | A1 | The prow on 1 faces r., on 4 1. The difference is significant, as the right-facing prow seems to appear on the very earliest coins of the issue. See pp. 87–89. |

| 5 | A2 | |

| 6 | A3 | |

| 8, 9 | A4 | The fulmen is slanted on 8; on 9 it is vertical, large, and crude. Alexander's illustrated example of 9 perhaps shows a recut symbol. Other vertical fulmens are smaller and more neatly executed. |

| 10, 11 | A5 | The rudder has tiller up on 10, down on 11. |

| 12 | B1 | |

| 13 | B2 | |

| 14 | B3 | |

| 20 | B4 | |

| 21, 22 | B5 | The Attic helmet faces r. on 21, 1. on 22. |

| 23 | B6 | |

| 29 | B7 | |

| 32 | B8 | |

| 36 | C1 | |

| 38 | C2 | |

| 39, 39A | C3 | The grain ear is vertical on 39, slanted on 39A. |

| 43 | C4 | |

| 44 | C5 | |

| 48 | C6 | |

| 51 | D1 | |

| 57 | D2 | |

| 58 | D3 | |

| 59 | D4 | |

| 61 | D5 | |

| 65 | D6 | |

| 66 | D7 | |

| 67 | D8 | |

| 70 | D9 | |

| 71 | D10 | |

| 73 | D11 | |

| 75 | D12 | |

| 76 | E1 | |

| 78 | E2 | |

| 79 | E3 | |

| 83 | E4 | |

| 84 | E5 | |

| 87 | E6 | |

| 89 | E7 | |

| 93 | E8 | |

| 99 | E9 | |

| 102 | F1 | |

| 103 | F2 | |

| 104 | F3 | |

| 105 | F4 | |

| 106 | F5 | |

| 108 | G1 | |

| 109 | G2 | |

| 110 | G3 | |

| 110A | — | The issue is described with AΛEΞANΔΡΟΥ BAΣIΛEΩΣ, and with dolphin 1. in 1. field; the reference is to Reattrib., issue 40 (pl. 9, 8). The symbol however seems to be merely a degenerated cornucopia of group G (as indeed Newell suggested, p. 33, n. 39), cut over the Athena Promachus of that group. Issue 110A is a phantom. |

| 111 | H1 | |

| 112 | H2 | |

| 113 | H3 | |

| 114 | H4 | |

| 115 | H5 | |

| 116 | J1 | Issues 116-17A are wrongly placed here, between groups H and I. They are merely part of group J. Alexander even, exceptionally (p. 86), notes obverse links between 117A (J2) and 124 (J6), and between 117 (J3) and 124. |

| 117 | J3 | |

| 117A | J2 | |

| 118, 119 | I1 |

Alexander lists and illustrates two variations,  and and  (actually (actually  as is clear from a cast at the ANS), of the usual monograms. See

85–66. as is clear from a cast at the ANS), of the usual monograms. See

85–66.

|

| 120 | I2 | |

| 121 | I3 | |

| 122 | J4 | |

| 123 | J5 | |

| 124 | J6 | |

| 125 | — | The issue is described with AΛEΞANΔΡΟΥ, and with wreath in 1. field and  below

throne. The reference is to Reattrib.'s issue LII-a, which there (p. 16) cites only Müller 548. Müller 548,

however, has only the wreath, no below

throne. The reference is to Reattrib.'s issue LII-a, which there (p. 16) cites only Müller 548. Müller 548,

however, has only the wreath, no  , and issue 125 is apparently a phantom. , and issue 125 is apparently a phantom.

|

| 126 | — | The coin is described as with  and "oak(?)-branch," but a dot is visible on the illustrated example,

joined to the bottom of the right vertical stroke of the and "oak(?)-branch," but a dot is visible on the illustrated example,

joined to the bottom of the right vertical stroke of the  . The illustrated example of 126 seems but one

of many poorly executed examples of group L, and belongs instead in issue 140, below. Issue is a phantom. . The illustrated example of 126 seems but one

of many poorly executed examples of group L, and belongs instead in issue 140, below. Issue is a phantom.

|

| 127 | — | The coin is described with  and filleted club, but a dot is clearly visible just to the left of and

below the right vertical stroke of the and filleted club, but a dot is clearly visible just to the left of and

below the right vertical stroke of the  . The coin belongs in issue 128, so issue 127 is a

Phantom. . The coin belongs in issue 128, so issue 127 is a

Phantom.

|

| 128 | L2 | |

| 129 | L3 | |

| 130 | L4 | |

| 131 | L5 | |

| 132 | L6 | |

| 133 | L7 | |

| 134 | — | The issue is described with AΛEΞANΔΡΟΥ, and with dolphin r. in l. field, and it is placed with the issues of

group L (with  ). The reference is to "Tetradrachms Amphipolis," issue 16,

which cites as a parallel a Philip II issue (Müller 211), which might seem to

suggest that the Alexander issue does belong at Amphipolis. The Philip issue is, however, decades earlier. See

Philippe

, Pella II.B, 410 ff. The present author strongly doubts that Alexander 134 was struck at Amphipolis. ). The reference is to "Tetradrachms Amphipolis," issue 16,

which cites as a parallel a Philip II issue (Müller 211), which might seem to

suggest that the Alexander issue does belong at Amphipolis. The Philip issue is, however, decades earlier. See

Philippe

, Pella II.B, 410 ff. The present author strongly doubts that Alexander 134 was struck at Amphipolis.

|

| 135 | [L3] | The wing described on the sole coin cited (here 93) would seem simply to be an aplustre, a symbol whose shape varies considerably. See 92–94. |

| 136 | L8 | |

| 137 | [L8] | The cowrie shell described on 137 is almost certainly merely a degenerated profile shield as on 136. |

| 138 | L9 | |

| 139 | L10 | |

| 140 | L1 | The issue, described with laurel branch and  , cites Müller 561, whose symbol is pictured like the

single straight upright laurel branch of issues J3 and J6. Two references are cited, the Aleppo 1893 hoard

(

IGCH 1516), and "Tetradrachms Amphipolis." Newell's transcript of the Aleppo hoard coins, however,

shows a forked branch as on issue L1. Citations in "Tetradrachms Amphipolis" reveal only coins as J6 (

Demanhur

1564 and Newell's list of the Kuft hoard) and L1 (Aleppo 1893 hoard, and

Walcher de Mollhein

1061). As no coins with , cites Müller 561, whose symbol is pictured like the

single straight upright laurel branch of issues J3 and J6. Two references are cited, the Aleppo 1893 hoard

(

IGCH 1516), and "Tetradrachms Amphipolis." Newell's transcript of the Aleppo hoard coins, however,

shows a forked branch as on issue L1. Citations in "Tetradrachms Amphipolis" reveal only coins as J6 (

Demanhur

1564 and Newell's list of the Kuft hoard) and L1 (Aleppo 1893 hoard, and

Walcher de Mollhein

1061). As no coins with  and straight laurel branch can be located, then, one can probably

safely discount Müller's description and consider that Alexander issue 140

is equivalent to L1. Issue 126, described as with "oak(?)-branch" (perhaps a better description than "forked branch") also

belongs in

issue 140. and straight laurel branch can be located, then, one can probably

safely discount Müller's description and consider that Alexander issue 140

is equivalent to L1. Issue 126, described as with "oak(?)-branch" (perhaps a better description than "forked branch") also

belongs in

issue 140.

|

| 421, 425, 426 | K2 | The three issues seem but three variations in the secondary marking. Alexander has separated 421–27 (

Demanhur

group K) from groups A–J and L and placed them at a different mint as the direct predecessors of the groups with  or or  and bucranium or torch, etc. See Alexander, pp.

86–87. This separation seems incorrect in the light of the four die links now known between posthumous Philip II issues as group J and others as group K. See below, Chapter 6, links 14–17. Further,

at least one obverse die link is known between group L and the Λ-bucranium Alexanders. See Chapter 3, link

22. and bucranium or torch, etc. See Alexander, pp.

86–87. This separation seems incorrect in the light of the four die links now known between posthumous Philip II issues as group J and others as group K. See below, Chapter 6, links 14–17. Further,

at least one obverse die link is known between group L and the Λ-bucranium Alexanders. See Chapter 3, link

22.

|

| 422 | K3 | |

| 423 | K4 | |

| 424 | K5 | |

| 424A | K6 | |

| 427 | K7 | |

| 428 | — | The issue is described withAΛEΞANΔΡΟΥ, and with A below the throne as the only marking. The reference given is "Tetradrachms Amphipolis," issue 5, which no doubt is derived in turn from a coin of this description at the ANS which was placed in its trays together with group K coins. Neither the coin's sole marking nor its style suggests any association with group K. I strongly doubt that the issue belongs at our mint. |

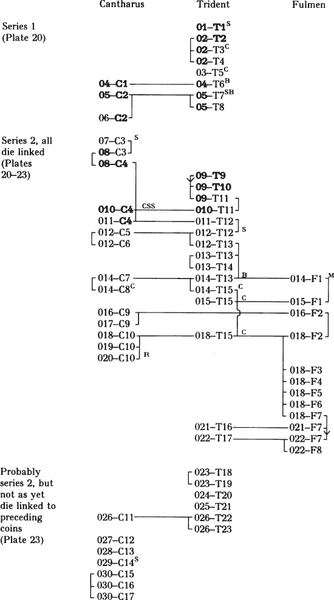

These smaller coins have received but one very brief study, by Newell in 1912.1 Table 3 presents the Alexander silver issues smaller than the tetradrachm: didrachms, drachms, triobols, diobols, and obols. All denominations have the obverse type of the tetradrachms, a beardless head of Heracles r., wearing lion's skin headdress. The various reverse types are noted after each denomination's heading in the table, and shown again in schematic form in Table 6, pp. 34–35. All coins are inscribed simply AΛEΞANΔΡΟΥ.

The first column in Table 3 gives the Newell tetradrachm group to which each issue belongs, and the specific tetradrachm issue number assigned in Chapter 1, if there is an exact correspondence. Some small coins' markings do not parallel any on the tetradrachms, but obverse links among the small coins securely place most of these non-parallel issues in group E, and the rest can be assigned with near certainty on other grounds.

The second column gives the coins' markings, and the third the plate reference for representative coins of the different issues.

Virtually

all known obverse dies are illustrated, the exceptions being the late issues with  or arrow markings. Issue

numbers in Alexander form the fourth column, and asterisks indicate the issues

illustrated there. Where I differ on the reading of markings, the Alexander

issue number is placed where I believe it belongs, but in parentheses. The fifth column gives the number of examples found

in each issue.

Brackets to left and right of the plate references indicate, as usual, obverse and reverse die links. All known die links

between issues

are shown. Issues of which I have seen no examples are shown in brackets, and are not counted among the examples located.

The drachms, the

commonest denomination, are divided between standing eagle reverse and seated Zeus

reverse.

or arrow markings. Issue

numbers in Alexander form the fourth column, and asterisks indicate the issues

illustrated there. Where I differ on the reading of markings, the Alexander

issue number is placed where I believe it belongs, but in parentheses. The fifth column gives the number of examples found

in each issue.

Brackets to left and right of the plate references indicate, as usual, obverse and reverse die links. All known die links

between issues

are shown. Issues of which I have seen no examples are shown in brackets, and are not counted among the examples located.

The drachms, the

commonest denomination, are divided between standing eagle reverse and seated Zeus

reverse.

Table 4 summarizes the numbers of examples found of each denomination in each group. Table 5 shows the number of obverse dies located (shared dies reduce the number by 0.5), again for each denomination in each group. It is remarkable how close to 2:1 the coin to die ratio is for each denomination and for each group except group A.

| Corresponding Tetradrachm Issue | Markings | Plate | Alexander Issue | Examples Found |

| Didrachms | ||||

| Rev.: Zeus seated 1. | ||||

| Group B, 1 coin | ||||

| B6 | Ivy leaf | 131 | 24* | 1 |

| Group C 14 coins | ||||

| C1 | Filleted caduceus | 132 | 37 | 2 |

| C2 | Quiver | 133 | (107) | 4 |

| C3 | Grain ear | 134 | 40 | 3 |

| Corresponding Tetradrachm Issue | Markings | Plate | Alexander Issue | Examples Found |

| C5 | Pegasus forepart | 135 | 45* | 4 |

| 136 | ||||

| C6 | Bow | 137 | 49 | 1 |

| Group D, 8 coins | ||||

| D4 | Horse head | 138 | — | 1 |

| D5 | Star | 139 | 62 | 1 |

| D7/8 | Caduceus  ( ( ? ?  ? ?

|

140 | 68 | 5 |

| 141 | ||||

| D9 | Club

|

142 | 72 | 1 |

| Group E, 8 coins | ||||

| E2 | Herm | 143 | 78A | 1 |

| E3 | Cock | 144 | 80 | 3 |

| E8 | Bucranium | 145 | 94 | 2 |

| 146 | ||||

| E9 | Caduceus | 147 | — | 2 |

| Drachms | ||||

| A. Rev. : Eagle, head sometimes reverted, standing l. or r. on fulmen | ||||

| Group A, 5 coins | ||||

| A1 | Prow | 148 | 2 | 4 |

| A3 | Double heads | 149 | 7 | 1 |

| Group B, 1 coin | ||||

| B6 | Ivy leaf | 150 | 2014 | 1 |

| Group C, 1 coin | ||||

| C3 | Grain ear | 151 | 40A | 1 |

| Group D, 9 coins | ||||

| D1 | Eagle head | 152 | 52* | 2 |

| D4 | Horse head | 153 | 60* | 5 |

| D- | Filleted caduceus

|

154 | 69 | 1 |

| D11 | Dolphin | 155 | 74 | 1 |

| Group E, 36 coins | ||||

| E1 | Rose | 156 | 77 | 2 |

| E5 |

: eagle on club : eagle on club

|

157 | 85 | 4 |

| E6 | Pentagram | 158 | 87A | 3 |

| E8 | Bucranium: vertical; | 159 | 95* | 1 |

| horizontal; | 160 | 96* | 4 | |

| eagle on thyrsus? or torch? | 161 | — | 1 | |

| E9 | Caduceus | 162 | (33*), 101 | 5 |

| 163 | ||||

| E- | No marking: eagle on caduceus; | 164 | 144 | 1 |

| E- | eagle on club; | 165 | 145* | 9 |

| 166 | ||||

| E- | eagle on thyrsus; | 167 | 148 | 4 |

| E- | eagle on torch | 168 | 151 | 2 |

| B. Rev. : Zeus seated 1. | ||||

| Group E, 6 coins | ||||

| E3 | Cock | 169 | 81 | 2 |

| E7 | Crescent | 170 | — | 1 |

| Corresponding Tetradrachm Issue | Markings | Plate | Alexander Issue | Examples Found |

| E8 | Bucranium | 171 | 94 A | 1 |

| E9 | Caduceus *- | 172 | 100 | 2 |

| 173 | ||||

| Group E or F, 13 coins | ||||

| E?F? |

|

174 | 141 | 10 |

| E?F? | Laurel branch | 175 | — | 3 |

| 176 | ||||

| Group F, 18 coins | ||||

| F- | Arrow | 177 | 50* | 18 |

| 178 | ||||

| 179 | ||||

| Triobols | ||||

| Rev.: Eagle standing 1. or r. on fulmen | ||||

| Group B, 2 coins | ||||

| B3 | Wreath | 180 | 15* | 1 |

| B6 | Ivy leaf | 181 | — | 1 |

| Group C, 2 coins | ||||

| C3 | Grain ear | 182 | 41* | 2 |

| Group D, 1 coin | ||||

| D5 | Star | 183 | 63 | 1 |

| Group E, 24 coins | ||||

| E2 | Herm | 184 | — | 1 |

| E3 | Cock head | 185 | 82 | 2 |

| 186 | ||||

| E4 |

|

187 | 86 | 2 |

| [E6] | Pentagrama | 88 | [1] | |

| E7 | Crescent | 188 | (53), 90 | 3 |

| 190 | ||||

| E9 | Caduceus | 191 | 34* | 5 |

| 192 | ||||

| E- | No marking: eagle on club | 193 | 146, (149) | 7 |

| E- | No marking L | 195 | 150, 154 | 7 |

| 196 | ||||

| Diobols | ||||

| Rev.: Two eagles standing facing each other, on fulmen or exergue line | ||||

| Group A, 1 coin | ||||

| A1 | Prow | 197 | 3 | 1 |

| Group B, 7 coins | ||||

| B6 | Ivy leaf: in center; to right | 198 | 25, (16)* | 6 |

| 199 | 25 A | 1 |

| Corresponding Tetradrachm Issue | Markings | Plate | Alexander Issue | Examples Found |

| Group C, 2 coins b | ||||

| C3 | Grain ear | 200 | 42 | 1 |

| C5 | Pegasus forepart | 201 | 46 | 1 |

| Group D, 7 coins | ||||

| D1 | Eagle head | 202 | 54* | 3 |

| D4 | Horse head | 203 | — | 3 |

| D5 | Star | 204 | 64 | 1 |

| Group E, 13 coins | ||||

| E8 | Bucranium | 205 | 98* | 1 |

| E- | No marking: eagles on club; | 206 | 147 | 3 |

| E- | eagles on torch | 207 | 152 | 1 |

| E- | No marking | 208 | 155* | 8 |

| Obols | ||||

| Rev.: Fulmen | ||||

| Group A, 1 coin | ||||

| [A1] | Prowc | 3A | [1] | |

| Group B, 4 coins | ||||

| B3 | Wreath | 209 | 17 | 1 |

| B6 | Ivy leaf | 210 | 26* | 3 |

| 211 | ||||

| Group C, 1 coin | ||||

| C5 | Pegasus forepart | 212 | 47 | 1 |

| Group D, 3 coins | ||||

| D1 | Eagle head | 213 | 55 | 3 |

| Group E, 9 coins | ||||

| E- | No marking | 214 | 157* | 9 |

| Group | A | B | C | D | E | E or F | F | Total |

| Didrachms | 1 | 14 | 8 | 8 | 31 | |||

| Drachms, eagle | 5 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 36 | 52 | ||

| Triobols | 2 | 2 | 1 | 24 | 29 | |||

| Diobols | 1 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 13 | 31 | ||

| Obols | 4 | 1 | 3 | 9 | 17 | |||

| Drachms, Zeus | 6 | 13 | 18 | 37 | ||||

| Totals | 6 | 15 | 21 | 28 | 96 | 13 | 18 | 197 |

| Group | A | B | C | D | E | E or F | F | Total |

| Didrachms | 1 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 14 | |||

| Drachms, eagle | 3 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 9.5 | 21.5 | ||

| Triobols | 2 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 14 | |||

| Diobols | 1 | 0.5 | 3 | 2.5 | 6 | 13 | ||

| Obols | 2.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 9 | 13 | |||

| Drachms, Zeus | 2.5 | 7 | 7 | 16.5 | ||||

| Totals | 4 | 7 | 11 | 15 | 41 | 7 | 7 | 92 |

Table 6 summarizes the issues known of the small coins. The obverse type of all denominations is the same as the tetradrachms'. The reverse types are indicated in the table by the following abbreviations:

Z = Zeus seated, as on the tetradrachms

EH = Eagle standing r., usually on fulmen

ERH = Eagle standing r., head reverted, usually on fulmen

EL = Eagle standing 1., usually on fulmen

2E = Two eagles standing facing, on fulmen or exergue line

F = Fulmen

Issues in Alexander of which no specimens have been seen by me are shown in brackets.

| a |

Alexander's

sole reference is to Reattrib., p. 14, XXXIV. This cites "Imhoof-Blumer," which presumably is Monn. gr., p. 119, 25, a coin of 2.10 g with pentagram symbol. This coin is from an unidentified private

collection and cannot be traced.

|

| b |

While this study was in page proof, Charles Hersh acquired a diobol with bow symbol corresponding to tetradrachm issue C6.

The litte

coin is from new dies. It is not illustrated, but it is included in Tables 4–6.

|

| c |

It has unfortunately not been possible to obtain a cast or photo of this coin, seen by Price in a private collection, but

there seems no

reason to doubt the issue.

|

| 1 |

Reattrib pp. 12–14 and 23.

|

It should hardly be necessary to state once again that these small coins, most with eagle as reverse type, are not subdivisions of the rare Alexander tetradrachms with eagle reverse.2 Those tetradrachms were struck to the old standard employed by Philip II, whereas the small coins are all of full Attic weight and most of their markings are clearly those of the Attic-weight tetradrachms of Chapter 1. The type of standing eagle with reverted head was simply an old Macedonian type continued by Alexander. It was used by Archelaus I, Amyntas III, and Perdiccas III,3 and the latter two, Alexander's grandfather and uncle, coupled with it the Heracles head obverse used by Alexander.

Unaware of the numerous obverse links now known between the many small coins without reverse symbols and those with symbols of group E, Alexander unfortunately has catalogued these no-symbol issues together with the eagle-reverse tetradrachms (while of course listing the symbol-bearing small coins together with the tetradrachms bearing their markings).4 All the small coins with eagle reverses can now, however, be associated with specific groups of the Attic weight tetradrachms. Together with the didrachms, which bear the tetradrachms' seated Zeus as reverse type, they are all simply subdivisions of the tetradrachms. It seems unnecessary to consider them a separate series struck "for local circulation" only.5

In groups A through D, the small coins' markings are exactly those of the tetradrachms, except for one drachm with filleted

caduceus and

which probably should be assigned to group D (the filleted caduceus occurs in both C and D,

but only in D are monograms found). The drachms of groups A through D all have the standing eagle reverse type.

which probably should be assigned to group D (the filleted caduceus occurs in both C and D,

but only in D are monograms found). The drachms of groups A through D all have the standing eagle reverse type.

As just noted, the numerous obverse links within group E, diagrammed in both Table 3 and Table 6, allow the firm placement within that group of a number of anomalous issues of drachms, triobols, and diobols whose attribution has heretofore been uncertain. These coins have no regular issue markings and often show the eagle standing not on the standard fulmen, but on caduceus, club, thyrsus, or torch.

By any standard–number of issues, number of examples located, or number of obverse dies found–group E had the largest output of small coins. This is not surprising, as E was also the largest group of tetradrachms. In this group, too, the drachms with the usual imperial Alexander drachm reverse of seated Zeus first appear, with issue markings identical to those of some eagle-reverse coins in the group, and actually obverse linked to one other eagle-reverse issue.

A drachm issue with the simple marking  has heretofore usually, and understandably, been associated with the

Alexander tetradrachms of group L, which bear the same primary marking.6 The presence now of several examples of the issue in the Near East 1993 hoard,7 however, buried perhaps ca. 322 (several years earlier than the great Demanhur hoard interred before

the striking of the

has heretofore usually, and understandably, been associated with the

Alexander tetradrachms of group L, which bear the same primary marking.6 The presence now of several examples of the issue in the Near East 1993 hoard,7 however, buried perhaps ca. 322 (several years earlier than the great Demanhur hoard interred before

the striking of the  tetradrachms of group L), shows that these drachms must be considerably earlier than

tetradrachm group L, and the absence of the title requires a group prior to groups G–K/J.

tetradrachms of group L), shows that these drachms must be considerably earlier than

tetradrachm group L, and the absence of the title requires a group prior to groups G–K/J.

Also in the Near East 1993 hoard were two drachms with laurel branch symbol, an issue previously unknown save for one example

published in

1988 by Kamen Dimitrov. This was one of three Alexander drachms forming a small hoard discovered in 1976 at Calim, in Bulgaria.8

Dr. Dimitrov has kindly sent me not only a direct photo of a cast of the coin (175), but

also a translation of his relevant Bulgarian text: ... Calim, ca. 35 km. W. from Nicopolis ad Nestum. Three Alexander drachms are kept in the Historical Museum of Blagoevgrad. ... According to the

control marking . . . [the coin in question] corresponds to the issue of Demanhur 1563, [J1, with laurel

branch but with the

omitted], Amphipolis 320–319.

At the same time the coin is struck from the same obverse die used for a specimen of an issue not represented in the Demanhur

hoard. ... [Sardes and Miletus, p. 87, 3 = 174].

omitted], Amphipolis 320–319.

At the same time the coin is struck from the same obverse die used for a specimen of an issue not represented in the Demanhur

hoard. ... [Sardes and Miletus, p. 87, 3 = 174].

The

Sardes and Miletus

issue cited, die linked with the Calim laurel branch coin, is the  issue. The laurel branch issue's

presence in the Near East 1993 hoard now shows that it too antedates 322/1 at the latest, and the absence of the title again

indicates a

group prior to groups G-K/J. No exact correspondences with any tetradrachms' markings exist for these two interesting issues,

but the

reverse variation and experimentation introduced in group E may in part explain their lack of correspondence. The obverses

of these

issue. The laurel branch issue's

presence in the Near East 1993 hoard now shows that it too antedates 322/1 at the latest, and the absence of the title again

indicates a

group prior to groups G-K/J. No exact correspondences with any tetradrachms' markings exist for these two interesting issues,

but the

reverse variation and experimentation introduced in group E may in part explain their lack of correspondence. The obverses

of these

and laurel branch drachms are extremely similar to many tetradrachms of groups E and F (e.g., 40–56). Their reverse exergue lines, too, with one dotted exception, are formed by a simple line, an innovation which

is known rarely among the group E tetradrachms, but which is common among those of group F.9 One of these

groups then must be that to which these

and laurel branch drachms are extremely similar to many tetradrachms of groups E and F (e.g., 40–56). Their reverse exergue lines, too, with one dotted exception, are formed by a simple line, an innovation which

is known rarely among the group E tetradrachms, but which is common among those of group F.9 One of these

groups then must be that to which these  and laurel branch issues belong.

and laurel branch issues belong.

Another Zeus-reverse drachm issue with arrow symbol has long been known. The arrow, which again does not occur on the tetradrachms,

could

be considered as associated with group C's bow or with F's bow and quiver.10 But, as other Zeus-reverse

drachms first appear in group E, these arrow-symbol drachms cannot be so early as group C. Again, the lack of the title rules

out groups

G-K/J. The obverse style of many arrow drachms, like that of the  and laurel branch drachms just

discussed, is very similar to tetradrachms of both groups E and F–but in the case of these arrow drachms, one iconographical

detail allows

a firm placement in group F. Just as on the group F tetradrachms, their exergue lines, instead of the normal dotted ones,

are sometimes

found as simple straight lines (177) or omitted altogether (179). And on at least one arrow

drachm (178) the footstool is indicated by the slanting "short straight line (not to be confounded with an exergual

line)" which is found only on the tetradrachms of group F.11 The arrow drachms can only belong to group

F.

and laurel branch drachms just

discussed, is very similar to tetradrachms of both groups E and F–but in the case of these arrow drachms, one iconographical

detail allows

a firm placement in group F. Just as on the group F tetradrachms, their exergue lines, instead of the normal dotted ones,

are sometimes

found as simple straight lines (177) or omitted altogether (179). And on at least one arrow

drachm (178) the footstool is indicated by the slanting "short straight line (not to be confounded with an exergual

line)" which is found only on the tetradrachms of group F.11 The arrow drachms can only belong to group

F.

No small Alexander coins are known after group F. As will be seen below in Chapter 4, the revived tetradrachms of Philip II, many of whose markings parallel those of Alexander tetradrachms, start possibly as early as group I, and certainly by groups K and J, continuing through L and several subsequent groups. Philip II fractions accompany these Philip tetradrachms through those parallel with Alexander groups K and J–and then, as I shall argue in Chapter 5, probably are discontinued before the Philip group parallel to Alexander's group L.

Finally, following group L and the tetradrachms with bucranium and Λ, Thompson has deduced from the existence of a plated ancient Alexander imitation drachm with Λ and torch that there may have been genuine Alexander drachms with those markings also.12 If so, however, none have yet been discovered.

Thus the small coins were as follows.

Groups A-D: Alexanders, several denominations, drachms with eagle reverse

Group E: Alexanders, several denominations, drachms with both eagle and Zeus reverses

Group F: Alexanders, drachms, Zeus reverse

Groups G-H: –

Groups K-J and perhaps I: Philips. See Chapter 5.

| 2 | |

| 3 |

E.g., BMC, pp. 165, 171–72, 176; SNGCop 505, 513–15, 522; SNGANS

94–96, 113.

|

| 4 |

Alexander

144–52, 154–55, 157. See Tables 3 and 6 and comments on 144–57, pp. 39–40. The association of the eagle-reverse bronzes of

issues

158–62 with the eagle-reverse small silver coins is also quite uncertain.

|

| 5 |

Alexander

, pp. 24, 88, and 103–4.

|

| 6 | |

| 7 |

Chapter 8, hoard 7.

|

| 8 |

Chapter 8, hoard 11.

|

| 9 |

See pp. 91–92, and 53.

|

| 10 |

| Alexander Issue | Denom. | Corresponding Tetradrachm Issue | |

| 2 | dr. | A1 | |

| 3 | 2-ob. | A1 | |

| 3A | ob. | [A1] | This is the coin seen by Price in a private collection. |

| 7 | dr. | A3 | |

| 15 | 3-ob. | B3 | |

| 16 | 2-ob. | (B6) | Described as with wreath between two eagles on reverse, the only coin cited actually has an ivy leaf (it is a die duplicate of several other specimens so marked, and the leaf is clear on Alexander 's illustration of 16). The coin belongs to group B's issue 25. No diobols with wreath are known to me. |

| 17 | ob. | B3 | |

| 24 | 2–dr. | B6 | |

| 25, | 25 A 2–ob. | B6 | The one coin known to me of issue 25A (199, with ivy leaf to right) is from the obverse of all five known examples of issue 25, with ivy leaf between two eagles (e.g., 198). Coin 199 is from the same die pair as Alexander's illustrated example of issue 54 and McClean 3509 (the symbol erroneously described as a bucranium), both with the eagle head of group D. The symbol of these last two coins has been cut over the ivy leaf of issue 25A. See also issue 54. Note the analogous recutting in the obols of groups B and D (issues 26 and 55). |

| 26 | ob. | B6 | The ivy leaf on the single reverse die of all three known specimens has been recut to an eagle head on the two known specimens of group D's issue 55. |

| 30 | ob. | [B7] | Newell in Reattrib. mentions this issue, but I have found no examples. Possibly an ivy leaf was seen as grapes. Compare issue 26. |

| 33 | dr. | E9 | Although listed in Alexander after the issues of group B, the shape of the issue's caduceus argues for a placement with issue 101 in group E.13 Issue 34, also with caduceus, is obverse linked with other E issues. |

| 34 | 3–ob. | E9 | Also listed after the group B issues, the issue belongs to group E. Of the four known examples, only three are in sufficiently good condition to allow die identification, and all three share their single obverse die with coins of group E's issues 82 and 149. |

| 37 | 2–dr. | C1 | The issue is perfectly valid. Note only that Lanz 48, 22 May 1989, 193, from the dies of the coin illustrated here (132), is erroneously described as bee on rose, and thus as a unique didrachm of Pella. |

| 40 | 2–dr. | C3 | |

| 40A | dr. | C3 | |

| 41 | 3–ob. | C3 | |

| 42 | 2–ob. | C3 | |

| 45 | 2–dr. | C5 | |

| 46 | 2–ob. | C5 | |

| 47 | ob. | C5 | |

| 49 | 2–dr. | C6 | |

| 50 | dr. | F– | See pp. 36–37 for the placement in group F. |

| 52 | dr. | D1 | |

| 53 | 3-ob. | (E7) | The issue is described with eagle head to right, but the sole known coin, at the ANS (188), seems on close examination to bear a crescent, with horns pointed downward–which is also the orientation of the same symbol in the exergue of a coin of issue 90 (189). Issue 53's flan and die sizes also accord far better with group E than with D, so that the coin probably belongs in issue 90. Issue 53 seems, at least from present knowledge, to be a phantom. |

| 54 | 2–ob. | D1 | The issue exists. See issues 25 and 25A for discussion of its recut symbol. SNGBerry 197, however, noted as an example, has not an eagle head but a horse head. Coin 203 clearly shows the horse's bridle. See issue 26 for discussion of the recut symbol. |

| 55 | ob. | D1 | |

| 60 | 2–dr. | D4 | |

| 62 | 2–dr. | D5 | |

| 63 | 3–ob. | D5 | |

| 64 | 2–ob. | D5 | |

| 68 | 2–dr. | D7/8 | Price calls the monogram  but its small size and condition on the known coins make it impossible to

be certain whether it is but its small size and condition on the known coins make it impossible to

be certain whether it is  or or  , or perhaps simply , or perhaps simply

|

| 69 | dr. | D- | The caduceus is filleted. |

| 72 | 2–dr. | D9 | |

| 74 | dr. | D11 | |

| 77 | dr. | E1 | |

| 78A | 2–dr. | E2 | |

| 80 | 2–dr. | E3 | |

| 81 | dr. | E3 | |

| 82 | 3–ob. | E3 | |

| 85 | dr. | E5 | |

| 86 | 3–ob. | E4 | |

| 87A | dr. | E6 | |

| 88 | 3–ob. | [E6] | See p. 21, note a. |

| 90 | 3–ob. | E7 | See also issue 53. |

| 94 | 2–dr. | E8 | The sale catalogue reference cited in Alexander has a caduceus, not a bucranium. |

| 94A | dr. | E8 | The two citations refer to the same coin, and the Giessener (Gorny) coin number should be 221. |

| 95, 96 | dr. | E8 | The symbol is vertical on 95 and horizontal on 96. |

| 97 | 3–ob. | Two examples are listed. The Hague (now Leiden) coin must be an erroneous citation. J. P. A. van der Vijn has sent photographs of the cabinet's only Alexander triobol, and it is from the dies of the other examples of 146. The bucranium on the Hersh coin cited seems to be merely the final Υ of the inscription and the coin thus is part of issue 150. Issue 97 seems to be a phantom. | |

| 98 | 2–ob. | E8 | |

| 100 | dr. | E9 | |

| 101 | dr. | E9 | Issues 33 and 101 both seem to belong to group E. |

| 107 | 2–dr. | C2 | The symbol is not the upright bow and quiver of group F (where the issue is placed) and G, but the simple quiver depicted in the slanting position of group C, where 107 shares its single obverse die with issue 45 (with group C's Pegasus forepart symbol). |

| 141 | dr. | E?F? | See p. 36 for the placement in group E or F. |

| 144 | dr. | E– | |

| 145 | dr. | E– | |

| 146 | 3–ob. | E– | The object on which the eagle stands is not perfectly clear, but does appear to be a club on the three examples known, which are all from the same die pair. See also issue 149. |

| 147 | 2–ob. | E– | |

| 148 | dr. | E– | The issue exists, but the eagle on the Weber coin cited (now at the ANS) seems to be standing on a club, not a thyrsus, and the coin thus belongs in issue 145. |

| 149 | 3-ob. | E– | The eagle is described as standing on a "thyrsus( ?)" and the sole example cited is now in the ANS collection. In fact it is the coin cited under issue 146, with eagle on club. It is from the dies of the Hague (now Leiden) coin also cited under 146, and those of another example of 146 in the Hersh collection. No triobols with eagle on thyrsus have been found, and issue 149 appears to be a phantom. |

| 150 | 3–ob. | E– | Some examples at least of issues 150, 154, 155, and 157 may be coins whose markings are off flan and which therefore belong elsewhere. The eagle stands to right on 150, to left on 154. |

| 151 | dr. | E– | |

| 152 | 2–ob. | E– | |

| 153 | dr. | — | Whether one accepts Thompson's attribution of this issue with  to Miletus

(Miletus

28-31), or Price's to "Macedonia ('Amphipolis')" it does not belong at our mint. to Miletus

(Miletus

28-31), or Price's to "Macedonia ('Amphipolis')" it does not belong at our mint.

|

| 154 | 3–ob. | E– | See comment at 150. |

| 155 | 2–ob. | E– | See comment at 150. |

| 156 | ob. | — | The reverse type of the sole coin cited is an eagle standing left, head reverted, on an uncertain object. Dr. Price kindly confirmed that the coin's poor condition made recognition of a symbol, if any; or reading of any inscription impossible. All other known obols in this Macedonian coinage have a fulmen as reverse type, and nowhere here in any denomination is there known an eagle with reverted head standing left. Small coins of Amyntas III, however, bear precisely the types of issues 156, similarly oriented (e.g., SNGANS 94–96), and thus the coin cited as the only example of issue 156 is probably of that earlier king. |

| 157 | ob. | E– | See comment at 150. |

| 11 |

Reattrib., p. 17. See p. 92.

|

| 12 |

"Cavalla," p. 40 (discussion of hoard coin 17).

|

| 13 |

See p. 21, note a.

|

Obverse links provide by far the most important evidence for the order of the Alexander groups. These links, together with group A's use of symbols found in Philip II's coinage (immediately prior or perhaps for a time contemporary), the presence of the title BAΣIΛEΩΣ on five of the groups, and certain repetitions of reverse markings put all the groups into a firm order, with the one exception of the minute group K (whose placement will be discussed below). Some small confirmation of this order is provided by other types of evidence–hoards, stylistic considerations, and the small denominations of Chapter 2.

The 22 die links which have been discovered between the various Alexander groups are detailed on the following pages and summarized in Figure 4. Tetradrachms provide all but five: links 6 (drachms), 7 (diobols), 8 (obols), and 15-16 (didrachms). All coins known from these obverse dies shared by more than one group are described as a possible aid to future researchers. For the same reason, Newell's provisional tetradrachm obverse die numbers are also given, as the ANS's casts and photo file cards are marked with these numbers.

Further intra-group connections of the tetradrachms listed via reverse links are mentioned in the discussion following each die link in order to demonstrate further the complexity of the die linkage between issues within the groups and to show that the issues directly involved in the links between groups are often clearly contemporary with other issues in their groups. The reverses of the coins listed are described by Newell group letter, my issue number, and symbol, e.g., "A2, stern," while "same die" indicates that the reverse die is that of the immediately preceding coin.

The evidence is extremely incomplete or there would doubtless be more instances of links such as link 3, where a die was used for group B, then for A, and then for B again.

Group A with Group B

Link 1, tetradrachms, Newell obverse 25

Stage 1

A2, stern (215) ANS; ANS

Stage 2

B7, grapes (216) Toronto

Stage 3

B7, grapes (217) cast marked "Demanhur"; Naville 6, 28 .Jan. 1924, 721, same die

Stage 4

B7, grapes (218) Ball 6, 9 Feb. 1932, 167, same die

Breaks in the lion's mane commence on the two coins in stage 1, and become ever larger in succeeding stages.

Link 2, tetradrachms, Newell obverse 28

Stage 1

B7, grapes (219) formerly ANS = Reattrib., pl. 7, 12; ANS, same die; Oxford = SNGAshm 2538; Morgenthau 342, 26 Nov. 1934, 189, same die

A2, stern (220) ANS, stern cut over 219's grapes; ANS = Reattrib., pl. 7, 11, same recut die; Saroglos

Stage 2

A2, stern (221) ANS

The reverse die of 219 and 220 is the same but, when used for 220, group A's stern symbol had been cut over B's grapes. As noted above, Newell illustrated coins with stern and grapes in Reattrib. to show their obverse identity, but did not recognize the reverse identity and recutting at the time (his evidently subsequent ticket in an ANS coin's box, however, does describe the recutting).

In stage 2 slight deterioration has appeared around Heracles' mouth.

Link 3, tetradrachms, Newell obverse 47

Stage 1

B2, amphora (222) ANS

Stage 2

A3, double heads (223) ANS; Beirut, same die; ANS cast from Tripolitsa 1921 Hoard, IGCH 84, same die

B2, amphora (224) Berlin, die of 222

Stage 3

A3, double heads (225) ANS; ANS

B2, amphora (226) ANS

In stage 1 there are no breaks in the dotted border at the top of the die, no break between Heracles' brow and the border, and no break in the field at the top of his nose. In stage 2 slight breaks have appeared in all three areas. In stage 3 the breaks in the border and at the brow are more pronounced, and the field behind the lion's mane is starting to deteriorate. Clearly at least some of A's double-head coins and B's amphora coins were struck simultaneously. The last coin listed, with amphora, is linked by a net of reverse and obverse dies to all seven of the other symbols of group B. All but one of these die links are found among coins in the ANS collection.

Link 4, tetradrachms, Newell obverse 40

Stage 1

A3, double heads (227) ANS = Reattrib., pl. 1, 8; cast marked "in trade, Cairo," same die; ANS; Knobloch FPL 33, Apr. 1968, 530, same die

Stage 2

B2, amphora (228) London = Alexander 13a; ANS, same die; ANS = Reattrib., pl. 1, 9; ANS

Only in stage 2 are there die breaks at the corner of Heracles' mouth and on his neck below the lion's jaw. The first ANS coin in stage 2 is linked by its reverse die to another in the ANS collection, which is from the obverse die of a third there, from the B6 ivy leaf issue.

Link 5, tetradrachms, Newell obverse 52

Stage 1

B1, cantharus (229) ANS

Stage 2

A4, fulmen (230) ANS; Egger 10, 2 May 1912, 592. same die, not illustrated but a cast is at the ANS

B1, cantharus (231) Saroglos, die of 229; Coin Galleries FPL 5.3 (1961), C19 = Coin Galleries, FPL 4.3 (1963), C18, same die

In stage 2 only, breaks have occurred at the corner of Heracles' mouth, and in the lion's ear. The cantharus coins are linked by a net of reverse and obverse dies to five of the seven remaining symbols of group B (all but B7, grapes, and B4, stylis).

Group B with Group D

Link 6, drachms

B6, ivy leaf (232) Hersh = Giessener 58, 9 Apr. 1992, 234

D1, eagle head (233) Hersh; London = Alexander 52 = Weber 2083

See also links 7 and 8.

Link 7, diobols

Stage 1

B6, ivy leaf in center (234) Paris = Traité IV, 2, 900, pl. 311, 7 = Reattrib., pl. 7, 8; London = Alexander 16, same die; Athens, same die; Aberdeen = SNGDavis D 141, same die; Hersh, same die

B6, ivy leaf to right (235) St. Petersburg

Stage 2

D1, eagle head (236) Hersh, cut over 235's ivy leaf; London = Alexander 54, same recut die; Cambridge, Eng. = McClean 3509, same recut die, symbol called bucranium

The reverse die of the coins of group D is that of the St. Petersburg example of group B, but with the ivy leaf recut to eagle head. See also links 6 and 8.

Link 8, obols

Stage 1

B6, ivy leaf (237) London = Alexander 26

Stage 2

D1, eagle head (238) Hersh, cut over 237's ivy leaf; Hersh, same recut die

The reverse die of all coins is the same, the ivy leaf having been recut to eagle head on the coins in group D. See also links 6 and 7. Also from this reverse die, in its first stage with ivy leaf, but from a different obverse die, are another ANS coin and a third coin in the Hersh collection (210).

Group C with Group D

Link 9, tetradrachms, Newell obverse 102

C2, quiver (239) ANS = Reattrib., pl. 3, 9; H. Schulman, 7 July 1970, 213, same die; ANS; Egger 40, 2 May 1912, 632, same die, not illustrated, but a cast is at the ANS

D1, eagle head (240) ANS; Weber 2082, same die; Reattrib., pl. 3, 10

A cast at the ANS (from link 10's obverse 117 and 240's reverse) associates obverses 110 and 117.

Link 10, tetradrachms, Newell obverse 117

C2, quiver (241) ANS

D1, eagle head (242) ANS; Thomas L. Elder, Remarkable Collection of Greek Tetradrachms... (New York City, n.d.), 71, same die; ANS; ANS; Malloy, 28 Feb. 1972, 322, same die; Berlin

The die is associated with that of link 9.

Link 11, tetradrachms, Newell obverse 116 = 121

Stage 1

C2, quiver (243) Athens

Stage 2

C6, bow (244) Egger 40, 2 May 1912, part of non-illustrated lot 631, but a cast is at the ANS; ANS, same die; Gillette, same die D1, eagle head (245) ANS

In stage 2, a die break appears in the central row of the lion's locks, and the field just below the locks is breaking down. Newell obverses 116 = 121 and 105 (link 12) are both found in a group C cluster of ANS coins linked by a network of obverse and reverse identities. The cluster includes all the remaining three symbols of group C.

Link 12, tetradrachms, Newell obverse 105

Stage 1

C3, grain ear (246) ANS

Stage 2

C2, quiver (247) ANS; Berlin

C3, grain ear (248) ANS

C4, trident head (249) ANS

D5, star (250) Cambridge, Mass. = Dewing 1122

In stage 1, there is a small die break just to the left of and below Heracles' ear. In stage 2 this break has enlarged, and new breaks have appeared at Heracles' nose and at the angle of his chin and neck (this last break has been cut away on 249). The die is associated with that of link 11.

Link 13, tetradrachms, Newell obverse 107

Stage 1

C1, filleted caduceus (251) ANS; cast marked "Pozzi," same die

D1, eagle head (252) Cambridge, Mass. = Dewing 1117; ANS; cast marked "Mrs. Brett," same die

Stage 2

D1, eagle head (253) ANS, die of 252; Saroglos, same die; ANS

In stage 2, a die break beginning in the field at Heracles' brow has greatly enlarged. The first ANS coin (251) shares a reverse die with another ANS coin whose obverse was used also for coins of C4 (trident head) and C6 (bow).

Link 14, tetradrachms, Newell obverse 109

Stage 1

C5, Pegasus forepart (254) ANS

Stage 2

D2, Macedonian shield (255) ANS

Die breaks are present at Heracles' nose in both stages of the die, but only in stage 2 is there also a break in the hair at his brow and deterioration in the upper left field.

The reverse die of 255 is shared with another ANS coin whose obverse was used for five other issues of group D,

namely, D1 (eagle head), D3 (club), D6 (filleted caduceus M), D8 (caduceus  ), and D10 (club

), and D10 (club  ) (see 26–27, 29, 32, 34 and 37) and with a third ANS coin whose obverse

was used also for D4 (horse head).

) (see 26–27, 29, 32, 34 and 37) and with a third ANS coin whose obverse

was used also for D4 (horse head).

Link 15, didrachms

Stage 1

C1, filleted caduceus (256) Hersh = Glendining, 7 Mar. 1957, 21; Lanz 48, 22 May 1989, 193, same die, but the symbol called bee on rose and the coin an unpublished didrachm of Pella

Stage 2

D5, star (257) ANS

D7, caduceus  (258) ANS; St. Petersburg, same die

(258) ANS; St. Petersburg, same die

Below the lower left lock of the lion's hair a small break appears only on the coins of group D.

Link 16, didrachms

C5, Pegasus forepart (259) Hersh = Giessener 58, 9 Apr. 1992, 229; London = Alexander 45 = Reattrib., pl. 7, 1, same die

C6, bow (260) ANS = Reattrib., pl. 15, 2

D4, horse head (261) Hersh = Giessener 60, 5 Oct. 1992, 114

D7, caduceus  or possibly D8, caduceus

or possibly D8, caduceus  or caduceus

or caduceus  (262)

Berlin

(262)

Berlin

The last coin, 262, is extremely worn, but the obverse does seem to be that of the other coins.

Group D with Group E

Link 17, tetradrachms, Newell obverse 159

D5, star (263) cast marked "Case"; ANS; ANS, same die

D11, dolphin (264) ANS

E1, rose (265) Copenhagen = SNGCop 672

Either the die or the flan was defective when 265 was struck, as the type is missing in a large arc around the upper edge of the coin's obverse. The small E1, with rose, is known from but three coins and two obverse dies. One die, here, is shared with group D coins; the other, with another issue of group E (40, 44). The rose issue could thus belong with either group D or group E, but is here left where Newell placed it.1 In either case, an obverse link between D and E results.

Group E with Group F

Link 18, tetradrachms, Newell obverse 361

Stage 1

E3, cock (266) ANS; Parke-Bernet, 16 Oct. 1968, 23, same die; Grabow 14, 27 July 1939, 244, same die; ANS

Stage 2

E3, cock (267) ANS; Münz. u. Med. FPL 333, Apr. 1972, 11

F3, cornucopia (268) ANS

In stage 2, a dot just to the left of and below the lion's ear has enlarged, and another break has appeared to the left of and below the first one, between the second and third locks from the top in the outer row of the lion's mane. The reverse die of 268 is shared with another ANS coin whose obverse was used also for a coin of F5 (bow and quiver).

Group F with Group G

Link 19, tetradrachms, Newell obverse 427 = 490

F4, Athena Promachus (269) ANS = Reattrib., pl. 9, 3

G2, Athena Promachus (270) ANS = Reattrib., pl. 9, 4; Petsalis, same die

Group I with Group J

Link 20, tetradrachms, Newell obverse 681

Stage 1

Stage 2

In stage 2, the obverse has suffered general deterioration, and looks "softer," with breaks at Heracles' nose and to the right of his ear, and in the lion's locks.

Link 21, tetradrachms, Newell obverse 702

I3,  (274) Stockholm; Berlin, same die

(274) Stockholm; Berlin, same die

J1, grain ear (275) ANS

The last coin, 275, is in extremely poor condition, but its reverse seems to be as described, without the

Group L with Λ-Bucranium Group

Link 22, tetradrachms, Newell obverse 896

L7,  dolphin (276) Athens from Lamia 1901–2 hoard (

IGCH 93

)

dolphin (276) Athens from Lamia 1901–2 hoard (

IGCH 93

)

Λ over bucranium in left field, E under throne (277) Saroglos; unidentified photo (278), same die

Although groups after L have not been examined in detail for this study, link 22 has come to my attention. Mando Oeconomides has verified that the Lamia hoard obverse and reverse casts are indeed of a single coin.

In Figure 4, solid brackets show tetradrachm links, and dashed brackets show links between smaller denominations. Brackets to the left indicate the 22 obverse links found between the Alexander groups, and those to the right show reverse links resulting from recutting of the reverse dies. Tetradrachms furnish 17 of the links and the remaining five are found among smaller denominations (which exist only in groups A through F). Arrows on the brackets show the order, when ascertainable, in which the dies were used. Numbers on the brackets are those of the links already described. Dotted brackets to the right indicate multiple identical reverse markings (groups F and G, J and L). As shown, groups G through K/J include the title BAΣIΛEΩΣ in their inscriptions.

| 1 |

See p. 22, note b.

|

Given the framework of obverse die links just detailed, other evidence does little more than confirm the order they provide. Still other observations are all perfectly consistent with the order in Figure 4 and will be discussed below in Chapter 9, in connection with the mint's absolute chronology'.

Hoards

As Newell long ago wrote, the Kyparissia 1892/93 hoard, with its coins of groups A through D only, showed these four groups to be the earliest struck. Karditsa 1925 included coins of C through I, seven contiguous groups. Five hoards ending with group J are known. Of these, Akçakale 1958 contained every group except A and the small K, and Demanhur 1905 and Andritsaena ca. 1923 included every group, even K.2

Style

Newell dealt with details of style and iconography, and the progression from group to group, at some length in Reattrib. His analyses cannot be improved by the present author, but such aspects as are relevant to absolute chronology, whether or not treated by him, will be discussed below in Chapter 9.

Small Denominations

Not surprisingly, the present study of the small Alexander denominations only corroborates the group order already established, although it does provide the only actual die links known between groups A and B and the rest of the coinage. The eagle-reverse coins of various denominations are found only in A through E, and only in E do the Zeus-reverse drachms come in, which then are the only small coin struck in the following group F. No small coins of Alexander's types are known after group F.

| 2 |

See Chapters 8 and 9 for fuller discussion of these hoards.

|

Newell stated in Demanhur , without giving specific examples or illustrations beyond those few presented in Reattribution, that the tetradrachm groups were all bound in sequence by a series of obverse dies linking one group to the next: "... group 'A' will possess certain dies that were used in its production and then were continued in use, in a slightly more worn condition, for group 'B.' Group 'B,' in turn, will be found to possess certain obverse dies that had already been used for 'A,' and others that were later used for 'C,' and so forth."3 This account of the groups' linkage is somewhat of a simplification. Newell knew most of the links presented above. He apparently did not know the B-D or D-E links, and he evidently did not realize until after Reattribution's publication that at least some of group B was contemporary with group A.4 Further, no B-C links such as he suggests have been located.

At least since the publication of Reattribution, group A has been recognized as the first, because three of its symbols (prow, stern, and double heads) are the same as those found at the end of the lifetime or early posthumous coinage of Alexander's father, Philip II.5 And, although its shape is different in the two coinages, Le Rider has suggested that the rudder, which occurs rarely in Philip's issues, is a possible fourth symbol relating group A to Philip's coinage.6

Group B, repeatedly linked to A, should be next. But the first modification of Newell's order is that here some overlap between groups must be accepted, because of the links where an obverse die was used first for a coin or coins of group B before being used for group A (links 2, 3, and 5 above), and because of the unique recutting of a symbol of group B to one of group A (see link 2).

Groups C and D, linked by no fewer than eight obverse dies, are clearly contiguous. Group D would at first seem to have followed C, because, of the five shared obverse dies whose priority of use can be determined, all five were first used for group C. A complication is, however, introduced by links 6-8, where drachm, diobol, and obol obverses were used both for B and for D, the two smaller denominations having had their reverse symbols recut from one of group B to one of group D.

Because of the large number of obverse links between A and B and between C and D (a pattern which does not recur), and because of the newly recognized B and D links, it now seems probable that A and B were struck concurrently at two adjoining locations, followed by C and D at the same two respective locations (workshops? adjoining rooms? adjacent anvils?). If group C had chronologically separated B and D, all three groups emanating from the same workshop, it is hard to see why new dies should have been cut for C, while B's dies were preserved unused until returned to service, recut where necessary, for coins of group D. But certainty is not to be had, and no great violence can be done by leaving Groups A through D in their traditional order.

Following group D, successive obverse links, the introduction and abandonment of the title BAΣIΛEΩΣ, and similarities in reverse markings make the groups' order inescapable except for the position of the minute group K.

I have placed K in the tables before J, although a strict linear order is probably misleading. More interesting than the placement of K, however, is the question of its very attribution to our mint. Newell in Reattribution published only one issue of the group (K3, its largest) and assigned it to an uncertain mint of Macedonia, Thrace, or Asia Minor. By the time of Demanhur's publication, however, he had placed it, although without comment, at Amphipolis.7

Price has now argued against this attribution, considering group K (the Λ group) as the immediate predecessor of the Λ- or

-bucranium and Λ- or

-bucranium and Λ- or  -torch series–which he considered struck at Amphipolis. He posited that groups A–I, J, and L belong together, but without

successors, at another mint, presumably Pella.8 I would not necessarily disagree with his suggestion that the mint for the huge output of groups A

through L and their successors may have changed at some point. His suggestion of an introduction at Pella with a subsequent

move to Amphipolis could possibly be true. But

this study attemps to deal with numismatic evidence only, and that evidence seems at the very least to contradict the division

at the

particular point that Price suggests. Precisely because his monumental work will inevitably and deservedly become the standard

reference

for Alexander's coinage, I should like to respond here in some detail to Price's

arguments.

-torch series–which he considered struck at Amphipolis. He posited that groups A–I, J, and L belong together, but without

successors, at another mint, presumably Pella.8 I would not necessarily disagree with his suggestion that the mint for the huge output of groups A

through L and their successors may have changed at some point. His suggestion of an introduction at Pella with a subsequent

move to Amphipolis could possibly be true. But

this study attemps to deal with numismatic evidence only, and that evidence seems at the very least to contradict the division

at the

particular point that Price suggests. Precisely because his monumental work will inevitably and deservedly become the standard

reference

for Alexander's coinage, I should like to respond here in some detail to Price's

arguments.

First, he assumes that the title of BAΣIΛEΩΣ, once dropped (as it was in group L) would stay dropped, that there would be no brief recurrence. This is surely correct.

Second, he states that group J (the  -group) follows directly on the symbol-only issues of groups A-I. This

also seems correct, although not for the reasons he gives.9

-group) follows directly on the symbol-only issues of groups A-I. This

also seems correct, although not for the reasons he gives.9

Third, he says that group L (the  -group) should follow directly on J for two reasons. One is that

-group) should follow directly on J for two reasons. One is that  is an elaboration of

is an elaboration of  : this is of course quite possible but not necessarily so. The

second reason is the shared symbols between J and L, which is quite convincing.10

: this is of course quite possible but not necessarily so. The

second reason is the shared symbols between J and L, which is quite convincing.10

And, as group L first drops the title BAΣIΛEΩΣ,11 Price concludes that there would appear to be no room in the sequence for group K (the Λ-group), which bears the title. It then, he says, will have been the direct predecessor, but at another mint, of the Λ-bucranium and Λ-torch groups. His reasoning is tight and would be persuasive, but the separation of group K from our mint seems almost certainly impossible in the light of the four die links now known between the posthumous Philips analogous to group K and those analogous to group J. Moreover, any suggestion that dies might have been transferred from J at our mint to K as the initial group at another mint is ruled out by the observation that in the Philip link where priority of use can be determined, the die was used for coins of group K before being employed for coins of group J.12

Yet it remains quite true, as Price has pointed out, that K does not logically fit in the sequence either before or after J. The resolution is again provided by the study of the contemporary Philip groups, some analogous to J and K, some not, but all so tightly and intricately obverse linked that the only explanation seems to be that all were more or less contemporary.13 The tiny Alexander group K, if also struck concurrently with J, which would seem likely, then presents no problem. Price's sequence A through I to J to L is preserved, yet K being contemporary with J means that our mint need not be divided into two, at least at the spot Price proposes.

And finally, link 22 above, between group L (with  ) and the Λ-bucranium group, seems to rule out Price's

sequence at his proposed second mint of group K (with Λ), Λ-bucranium, Λ-torch.

) and the Λ-bucranium group, seems to rule out Price's

sequence at his proposed second mint of group K (with Λ), Λ-bucranium, Λ-torch.