Ten years after the first conference and volume on The Medal in America , we return with new studies on the topic. The two sets of papers have much in common, a result of the way in which the medal is viewed in this country. In general terms, the medal in America is approached as three distinct subjects, each exemplified in this year's conference. The medals of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century are treated as subjects for historical and numismatic inquiry, while those of a century later are objects of art historical analysis. American medals since the First World War are scarcely considered worthy of scholarly study at all.

The paper in this volume by John Adams is a preview of his forthcoming book on a series of Indian Peace Medals which are among the most intriguing in the series, those in the name of George III . The heraldic group is problematic enough, with the portrait of a young king paired with shields from both early and late in his reign, but the "Lion and Wolf" medal has long been a complete mystery in terms of date, iconography and purpose. Adams has combined extensive documentary and numismatic research to his solution to these questions. Chris Neuzil's paper on Moritz Fürst is an example of the most basic and valuable tool in medallic study, a fully documented corpus of the work of an artist set into a biographical narrative. It is of special importance in covering the work of an artist of major importance in the early development of the American medal, and one whose work has been little known until now. The paper of Paul Rich and Guillermo De Los Reyes on Masonic medals is more of a plea for inclusion and introductory overview than a detailed study. Medals, decorations and tokens of fraternal organizations have long been relegated to the edges of medallic inquiry, even though they had an enormous presence in the culture of the times.

Five of the papers in this volume deal with what has become the core area of study for the art of the American medal, the period from the Columbian Exposition to the First World War. Thayer Tolles tells the tumultuous story of the most important medal by the most influential of American medalists, the Columbian Exposition Award medal of Augustus Saint-Gaudens . Three authors treat the works of individual artists with comprehensive surveys of their work. Barbara A. Baxter writes on the classical nature of the work of one of the leading members of the first generation of American Beaux-Arts medalists, A. A. Weinman . Scott Miller examines and catalogues the medals of Emil Fuchs , important in the turn-of-the-century sculpture of England as well as America . Bob Mueller treats the use of mythological iconography in the medals of Paul Manship , an artist whose work can be seen as the culmination of the Beaux-Arts movement in America and the basis of the Art Deco style which dominated figurative sculpture here for much of the twentieth century. In her essay on Charles De Kay and the Circle of Friends of the Medallion, Susan Luftschein deals with issues of patronage and reception, situating the art medal in the aesthetic development of the age.

The contributions of the conference and this volume to the American medal of the late twentieth century are only potential. The Sunday workshops of Virginia Janssen and Ron Landis were of great interest to historians of the medal in illustrating the processes of many of the phenomena to be studied on the objects themselves, but may have even more importance for their effect on the artists present, who could see traditional techniques employed in the hands of modern practitioners.

What would we like to see in a third volume of The Medal in America , perhaps in 2007? There are eight decades of American medals between the War of 1812 and the Columbian celebration of 1892 which remain virtually unexplored and uncatalogued; leading medalists such as C. C. Wright and George H. Lovett remain little more than names to modern scholars. From the perspective of the next century, we should be able to look back at the twentieth century and find much of interest in the American medals of its last eight decades. And, of course, there will already be a few years of the twenty-first century American medal to subject to examination and study.

Alan M. Stahl

Conference Chairman

Coinage of the Americas Conference at the American Numismatic Society, New York

November 8-9, 1997

é The American Numismatic Society 1999

The reign of George III lasted for 60 years, from 1760 to 1820. This period spans the War of the Conquest, Pontiac's Revolt , the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. Our interest in George III centers on the Indian Peace Medals issued in his name. These medals tell a story at two levels. At the numismatic level, the story has been told by such distinguished hobbyists as Robert McLachlan (1882), C. Willys Betts (1894), Victor Morin (1916) and Melville Jamieson (1936). Much of what has been written by these authors is in error. We attempt to correct the earlier errors, proceeding further to define die varieties, methods of manufacture and quantities issued.

More important than the story at the numismatic level is the story at the historical level. The peace medals of George III tell an eloquent, if cynical, story of relations between the white man and Native Americans. This story spans many of the critical turning points in the development of a continent. The paper that follows attempts to summarize key findings that will be treated at greater length in a book in press for 1999 ( Adams 1999).

George the Second died on October 24, 1760, and his 22 year old grandson was proclaimed the following day. The coronation of George III took place on September 22, 1761, followed almost immediately by his marriage to Charlotte of Mecklenberg . Newly crowned and newly wed, the young King was also basking in the glow of his grandfather's victories. In the prior year, Wolfe had defeated Montcalm before Montreal, driving the French from Canada after a long, bitterly contested war.

Indians played a prominent role in the so-called "War of the Conquest." The Six Nations of the Iroquois League had fought on the side of the British. The Seven Nations of Canada had fought on the side of the French, as had the tribes in the Great Lakes region—the Ottawas, Chippewas, Hurons and Pottawatomies . On the western border of Pennsylvania , the Delawares and Shawnees had begun the war as allies of the colonials but then switched sides to the French before switching back as momentum swung to the British.

Originally, each colony had conducted its own Indian affairs. In large part because of the troubles in Pennsylvania , George II decided to centralize the responsibility for relations with the Indians. The new Superintendent of Indian Affairs bypassed the colonial governments, reporting directly to the Commander in Chief for North America . From 1755 until his death in 1774, Sir William Johnson held the position of Superintendent in the Northern District. In 1760, at the beginning of the reign of George III , the Commander in Chief was Major General Jeffrey Amherst . He was succeeded in 1763 by General Thomas Gage of Bunker Hill fame.

A large landowner in upstate New York , William Johnson began his career as a trader, assuming the ways of the Indians and learning their language. Adopted by the Mohawks , the easternmost of the Iroquois nations , Johnson enjoyed a special relationship with the natives. It was he who saw the inroads being made by the French , prompting him to recommend a centralized approach to Indian relations ( Johnson 1754). With his appointment to the Superintendency, Sir William soon became the most notable figure in colonial America . He led combined British-colonial-Indian forces to important victories over the French at Lake George and Niagara . With his Indians, he accompanied Wolfe to the climactic battle for Montreal in 1759.

Johnson started for Montreal with over 500 Indians but, between whimsical desertions and regular disagreements with the British military establishment, ended up with less than half that number. However, his supreme accomplishment was persuading the French Indians to remain neutral. Pierre Pouchet wrote in his memoirs " Johnson alone was able to quiet them and make them forget their ancient political system in this war" ( Pouchet 1866, 1:30). Indeed, Johnson was the only figure in colonial America respected by the Indians, the colonists and the British alike.

For his part, Amherst had a low regard for Indians. Nonetheless, it was he who recommended the so-called " Montreal medal" to Johnson and then saw to its execution ( Johnson 1921, 10:461). Johnson viewed the medals as a reward for service whereas Amherst considered them an identification badge by which "good" Indians could be distinguished in the future.

In their paper in The Medal in America , Fuld and Tayman did a commendable job of describing both the Montreal medals and the Happy While United medals of 1764 and 1766 ( Fuld and Tayman 1988). We will elaborate on these issues in our forthcoming book. Suffice for now to observe that there is an ironic connection between the two. Having eliminated the French, Amherst decided to suspend the sale of guns, powder and other supplies to the Indians and bar their entrance into British forts (save, presumably, for those natives wearing Montreal medals). The hard line taken by Amherst led to growing unrest, culminating in the conspiracy of 1763. Indeed, the Pontiac Conspiracy is often called " Amherst's War" by modern historians.

1. Medal for the wedding of George III and Charlotte , ANS 1925.173.5 .

By long tradition, the George and Charlotte medal has been attributed to 1761 ( fig. 1 ). Robert McLachlan writes " George III was married September 8, 1761. On this occasion, the Indians, ever profuse in their expressions of loyalty, forwarded to the 'Great Father' an address of congratulation, which the King gratefully acknowledged by causing these medals to be struck and distributed among the faithful red men" ( McLachlan 1882, 11). This statement is romantic balderdash. There were very few "faithful" Indians to be found— Amherst had seen to that.

The undated George III peace medals of standard design—"standard" meaning portrait on obverse, arms on reverse—come in three sizes: 76mm, 60mm and 38mm ( figs. 2 and 3 ). The George and Charlotte medal shares its reverse with the standard medal of 38mm diameter. The latter is extremely rare; indeed only two specimens are now known. Thus, it seems logical to hypothesize that the obverse die for this medal broke early its life and that the obverse of a previously unused marriage medal was employed in its place.

The "Lion and Wolf" medal has been similarly misplaced ( fig. 4 ). C. Willys Betts deserves the blame for this mistake, because it was he, reasoning from a specimen found in the grave of Pontiac's son, who then pioneered the theory that the skulking wolf represented Pontiac with the rest of the scene depicting the bliss to be had by those adhering to the British side ( Betts 1894, 238). This flight of fancy was swallowed whole by subsequent writers including McLachlan (1899, 16), Morin (1916, 35) and Jamieson (1936, 13).

2. George III Indian Peace Medal, reverse arms pre-1801, ANS 1923.52.7 .

3. George III Indian Peace Medal, reverse arms post-1801, ANS 0000.999.32881 .

In attributing the son's medal to the father, Betts ignored the matrilineal customs of Pontiac's tribe, the Ottawas. More obviously, he failed to explain why the great chief would have been pleased to receive a medal on the reverse of which he was caricatured, much less a medal of the medium-size generally issued to lesser figures. Further, none of the early writers observed that Lion and Wolf shares its obverse with the standard George III medal of the same diameter.

4. George III Lion and Wolf Medal, ANS 0000.999.32901 .

Thus, both the Lion and Wolf and the George and Charlotte medals are die-linked to the undated George III medals of standard design. Most likely, all of these pieces were made during the same period. Our thesis is that the undated peace medals of George III were made beginning in 1776 and continued to be made until dated medals appeared in 1814.

Our case requires two proofs. The first is that the medals were not made at the outset of the reign of George III (1760) or at any time up until 1776. The second proof required is that they were made thereafter. We have uncovered an abundance of contemporary evidence to support both points.

After conquering the French, the British should have renewed ties with their Indian allies as well as initiating relations with the greater number of Indians who had fought against them. Instead, they took a more short sighted view reasoning that, with the French threat removed, the money previously devoted to Indian presents could be saved. This attitude was well expressed by Amherst writing to Johnson in 1761: "Yet I am of opinion that we must deal sparingly, for the future ... I can see little reason for bribing the Indians or buying their good behavior, since they have no enemy to molest them" ( Johnson 1921, 10:348). The Indians were quick to sense the adverse change in their situation. In reporting to London in the Spring of 1762, Sir William Johnson wrote: "On inspecting my transactions of last year, and the later meeting your Lordship will observe that the Indians are not only very uneasy, but jealous of our growing power, which the enemy [i.e., the French] had always told them would prove their ruin, as we should by degrees surround them on every side, and at length extirpate them" ( Johnson 1921, 10:461).

The "late meeting" referred to by Johnson was a council with the Great Lakes Indians at Fort Detroit in the Summer of 1761. This was the first formal meeting held by the English with the most powerful tribes that had fought on the side of the French. Notwithstanding the importance of the occasion, minutes of the meeting reveal no issue of medals or, as protocol would have demanded, exchange of French medals in their place. In contrast, minutes of the councils at Niagara in 1764 and Oswego in 1766, for which the Happy While United medals were procured, describe such exchanges. Furthermore, Ensign Gorrell , who was sent to Michillimackinac , the second most important post in the West, wrote that his predecessor was asked by the Indians for medals in 1761 but there were none to give out then or now ( Gorrell 1903 1:33[6/25/1762]; 1:38[5/18/1763]). Thus it seems clear that no medals were given out in 1761 and 1762.

During the year 1763, the frontiers were aflame with Pontiac's Revolt . For the treaties held in 1764 and 1766 there is ample documentation in the papers of General Gage and Sir William Johnson that the medals issued were of local manufacture. Indeed, Johnson complained about the quality of this work because the French medals being exchanged were both finer and thicker ( Johnson 1921, 12:23). Gage responded: "I will inquire whether there is any good engravers at Philadelphia . The die in my possession was done by one de Bruls who was reckoned the best in these parts of the world" ( Johnson 1921, 12:34). 1

Despite the existence of a local source, medals remained in short supply. In 1765, Indian agent William Howard wrote from Michillimackinac that three important chiefs requested medals but he had none to give out ( Johnson 1921, 11:806-7). George Croghan , who was one of Johnson's most active lieutenants, took Happy While United medals on his mission to the Illinois in 1765 but, in early 1767, was forced to order 20 silver medals from Myer Myers , a silversmith in New York ( Johnson 1921, 12:265). Thus, there is no evidence of English-made medals being issued from 1763 through 1767.

Nowhere was the lack of quality medals felt more keenly than in the case of the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768. Preparing more than two years in advance for an event that would cede 20,000,000 acres of Indian land to the Crown, Johnson wrote to his civil supervisor at the Lords of Trade: "In my last letters I mentioned what the Indians then inclined to agree to with regard to the boundary between us and them ... and with the assistance of a proper present and some good medals [i.e., English made] struck on the occasion for the chief sachems and principal warriors, I do not despair of effecting it" ( Johnson 1921, 12:32). Incredibly, the Lords of Trade denied this modest request as well as subsequent applications for medals to be issued at following councils. Benjamin Roberts , Sir William's agent in London , reported the bad news: "I spoke to him about the medals, upon the whole his answer was that he would not augment the expense" ( Johnson 1921, 7:607). And again, "also the article of the Medals but he still persisted in thinking a limit should be fixed to the expense" ( Johnson 1921, 7, 732). In effect, His Majesty's government graciously accepted the 20,000,000 acres for which é15,000 had been paid but it would not spend another one hundred pounds to dignify the occasion.

After the Treaty of Fort Stanwix and its confirmations, the Indians became a forgotten force. Johnson's budget was greatly reduced, as trou- bles with the colonists moved to center stage. Seven years later, the situation was wholly reversed. With both the colonists and the British seeking allies in the struggle that began at Lexington , the Indians held the balance of power. Both sides conducted councils, vying to gain influence. The "peace" medals awarded in the process are enduring symbols of this hypocritical courtship.

In our book, we will discuss the individuals who promoted the use of medals as well as what can be learned in the absence of mint records for this period. Suffice for now to observe that British medals appear as early as June 5, 1776, when a German officer describes a reception held in Montreal , "After the ceremony was over, the General [Governor-General Sir Guy Carleton ] ordered uniforms ... for these chiefs, and presented them with big silver medallions upon which the likeness of the King was stamped" ( Du Roi 1911, 38). A few months later, similar treatment was accorded to Wabasha, the legendary chief of the Mdewankton Sioux and his companion, "The Governor presented each chief with a large silver medal bearing a bust of King George on the obverse side and Great Britain's coat of arms on the reverse. These were hung around their necks on ribbons of royal purple. Wabasha wore his above a similar French medal" ( Stevens 1990, 46).

Many more such references have been located in archives on both sides of the Atlantic . In our book, we explore at length the likelihood that the 300 "Burgoyne medals" ( Clinton 1900, 2:781) given out at Fort Niagara in December 1777 were of the Lion and Wolf design. Nonetheless, the first explicit mention of this medal we have located is in a letter dated 4/7/1781 which lists: "50 large silver medals with the Kings bust, the Lion, Wolf, etc." ( Knox 1781). Our earliest citation for the George and Charlotte medal occurs on an indent written in 1777 listing "70 silver medals, King and Queen's" ( Knox 1777). Thus, both George-and-Charlotte and Lion-and-Wolf can be ascribed with certainty to the Period of the Revolutionary War. Notwithstanding an extensive search of archives on both sides of the Atlantic , no earlier references to these or any of the undated George III peace medals have been found.

After the Treaty of Paris in 1783, the British continued to award peace medals to Indians in the Great Lakes region as well as to a few tribes west of the Mississippi . With the advent of the War of 1812, there was another surge in issuance culminating with the new, dated design in 1814. As our census (see below) would suggest, there were half as many of the 1814 medals distributed in a few years as there were undated medals awarded over a few decades. By the year 1815, the demand was pretty well saturated: "Formerly a chief would have parted with his life rather than his medal. Now very few think it worth preserving" ( Bulger 1815, 13:114).

George III medals got off to a very slow start in U.S. numismatics. Early commentators thought them rarer than the French counterparts. Indeed, the Bushnell Collection, one of the great treasure troves of Americana , contained but a single example.

The cause of the initial scarcity of George III medals is eminently logical: having fought on the side of the British in the Revolutionary War, most of the recipients chose to relocate in Canada . Thus, it wasn't until important Canadian collections came on the market that the supply began to improve. The Gerald Hart sale in 1888 contained four specimens; the Hunter (1920) and W.W. C. Wilson (1925) collections contained many more.

In point of fact, thousands of the George III medals were made—perhaps tens of thousands. We list several hundred in the condition census in our book. With specimens residing among Indians and in small institutions across Canada , we are confident that more examples will be available to numismatists as time wears on.

Jamieson (1936) lists a number of die varieties of the George III medals of which two are duplicates. All in all, his was a good first effort but we will describe a number of additional die varieties in our book. So numerous are the dies that one could infer from their number alone a total emission of 60,000 to 100,000 pieces. This estimate is almost certainly high; two other approaches described in our book yield estimates ranging between 5000 and 15,000.

The large medals were manufactured by one of three processes:

In the absence of mint records, one can only speculate as to why three methods of manufacture were employed. It seems logical to hypothesize that methods #2 and #3 were used to save money: Method #1 consumed more than twice the silver required for #2 and for #3. Data on weight, diameter, styles of hanger and other such features are now being gathered.

As a check on relative rarity, as well as to minimize duplication, we have designed our census in two parts. The first includes collections, auction appearances, and fixed price lists from 1860 to 1975. The second or modern census extends from 1975 to present day. As can be seen from Table 1, the two censuses reveal quite similar results. Thus one can be tolerably confident that the large undated medals of George III are the most common, followed by the large 1814s, Lion-and-Wolf and George-and-Charlotte in that order. The small undated medal of George III is by far the rarest of the group, which gives rise to our theory that the obverse die broke early in its life, leading to the substitution of George-and-Charlotte .

| Early | Late | ||

| Large George III | 62 | 61 (7 shells) | |

| Medium | 12 | 12 | |

| Lion & Wolf | 21 | 20 | |

| Small | 1 | 2 | |

| George & Charlotte | 10 | 15 | |

| 1814 Large | 33 | 26 | |

| 1814 Medium | 7 | 9 | |

| 1814 Small | 3 | 6 | |

| Montreal Medal | 7 | ||

| Happy While United | 18 |

If the medium-sized medals were issued to warrior chiefs and the small ones to ordinary warriors, one or both must have been made in much greater quantities than the large designs intended for the political chiefs or sachems. One explanation for the lower survival rate is alcohol: Indians were all too easily addicted to spirits and, given the silver content, medals must have been a fungible source of payment. At formal councils with the white men, chiefs made frequent complaints about the volume of rum dispensed by the traders but only a handful of tribes were successful in barring the substance from their dominions.

Inasmuch as chiefs drank at least as copiously as warriors, the higher survival rate of the large medals can probably be attributed to inherent political value. Within the Indian community, chiefs' medals were a confirmation of authority. Outside the community, chiefs were expected to wear their medals as symbols of loyalty to the Great White Fathers.

Whereas our census captures relative rarity, the total population now extant can only be guessed. The several hundred examples listed in our book could be relatively complete. More likely, in our opinion, is that another one to three times as many await re-discovery. Only time will tell. Whatever the ultimate census may show, it is clear that the population of George III medals is greater than generally thought. The good news is that they are sufficiently available to be an eminently collectable item.

The generals of George III regarded native Americans as idle, drunken and undependable. For their part, the Indians regarded the British as grasping and deceitful. Both sides had their points.

From an historical perspective, the medals of George III serve to sift through conflicting opinions and create a demonstrable fact: the British policy toward Indians was entirely self-serving. When, as was the case in the 1760s, the government placed a low value on the good will of the North American natives, the medals issued to them were small and/or of crude workmanship. When, with the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, the services of the Indians became indispensable, the medals got bigger and better.

Be it said that the medals of George III do more than enshrine the hypocrisy of His Majesty's government. They recall the enlightened Superintendency of Sir William Johnson . They mark the ebb and flow of events from the triumph at Montreal in 1759, to the disasters of Pontiac's revolt , to the attempt to create a permanent boundary at the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768. With the Revolutionary War, the issue of medals reached a crescendo, commemorating the early battles for Montreal , Burgoyne's disastrous campaign, the border wars of New York and formal alliances in the West. Medal-giving reached another, smaller, peak during the War of 1812. Indians played prominent roles at Detroit, Chrysler's Farm and Chateaugay .

Without denigrating the peace medals issued by our own government, we note that the medals of George III mark a period when the Indians were still a force on the scene. These medals mark the last period during which Indians played at center stage. They recall the independence, the bravery and the cunning of proud cultures that were soon subsumed by the tide of events.

| 1 |

The individual cited was Michael de Bruls of New York City . He deserves credit for

fabricating the dies for the Happy While United medals. The role of D.C. Fueter , more limited than long

supposed, was to make casts from the dies supplied by de Bruls . Who made the molds for the

Montreal medal becomes an open question.

|

Coinage of the Americas Conference at the American Numismatic Society, New York

November 8-9, 1997

é The American Numismatic Society 1999

Artist and die engraver Moritz Fürst was 26 years old when he came to America from Europe in late 1807. Between 1807 and about 1840, when he returned to Europe , he hand-engraved the dies for numerous Congressional award medals for the War of 1812 as well as presidential portrait dies for 12 different Indian Peace Medals. He also made a large number of medal dies as private and institutional commissions and, apparently, as speculative ventures. The medals from these dies preserve a remarkable collection of portraits, allegorical representations, historical scenes, and other iconography of early nineteenth century America .

Inexplicably, Fürst has received scant attention from numismatists. Although many of his medals have been described in various publications, notably the compilations of American medals by Loubat (1878) and Julian (1977), the only attempt to catalogue Fürst's American medals specifically was by Chamberlain (1954b) more than 40 years ago. A great deal has been learned since Chamberlain's pioneering study, but the findings have not been collected and organized, and some of Fürst's medallic work remains unpublished or unrecognized. Moreover, Fürst himself remains a shadowy figure, with many questions surrounding his professional and personal life.

In this paper I examine Fürst's career and present an updated compilation and discussion of his American medals. Both a census of Fürst's medal dies in tabular form and an illustrated catalogue of medals from the dies are included, and appear in an appendix. The die census is useful for analysis because many of Fürst's dies were paired with more than one of his other dies, with dies of other makers, or used without mate dies. In addition, it is the dies rather than the medals that measure Fürst's output and provide a framework for understanding his engraving career.

Fürst was born to Jewish parents in the town of Boesing, near Pressburg , Hungary (now Bratislava , Slovak Republic) in March 1782 ( Dunlap 1834, 221). Little is known about his early years. His training took place in Vienna , then about a two-day journey from Pressburg . There, Fürst relates ( Dunlap 1834, 221), he studied die sinking under Johann N. Wirt , the engraver at the Vienna Mint. Wirt directed an Academy of Engraving ( Forrer 1904, 6:567), and Fürst presumably was a student there. Figure 1 presents an example of Wirt's medallic work. Later, Fürst studied under an engraver named Megole , who superintended the mint in Lombardy, Italy ( Dunlap 1834, 221). Megole had earlier been in Vienna , perhaps also as Wirt's student, and it is likely that he met Fürst there. While working in Italy , Fürst made the acquaintance of Thomas Appleton , the American Consul in Livorno .

Fig. 1. Austrian medal by Johann N. Wirt . Fürst studied engraving under Wirt in Vienna , probably at Wirt's Academy of Engraving. The medal honors the erection of a monument to Joseph II in 1806, and features a bust of Francis II on the obverse.

A pamphlet published by Fürst , or on his behalf, in about 1825 (Proceedings n.d.) outlined the artist's version of his intercourse with Appleton . Fürst engraved seals for the Consul, whereupon Appleton requested a meeting with the engraver through Francis Wittenberg , who acted as Fürst's business agent. The pamphlet describes Appleton , after some discussion of coinage designs, explicitly offering Fürst a position as engraver at the U.S. Mint with an annual salary of $2,000. The offer was later attested by Wittenberg , whose notarized statement to that effect appears in the pamphlet. Fürst recounts that he accepted the offer and sailed with Wittenberg to New York , arriving in September 1807 (Proceedings n.d.).

As represented in the pamphlet, Appleton's offer is difficult to reconcile with events that followed. It seems unlikely that Appleton had authority to engage an engraver for the Mint, particularly at a salary of $2,000; by the time Fürst arrived in America , the German-born engraver John Reich had been hired, at a salary of $600, to assist Mint engraver Robert Scot . Fürst eventually met with Mint Director Robert Patterson , Chief Coiner Henry Voigt , and Reich (Proceedings n.d.). However, Patterson apparently did not offer him the position he expected.

Although we do not know what transpired in his meeting with Patterson, it is clear that Fürst believed that he would eventually obtain the promised appointment (Proceedings n.d.). 1 He took up residence in Philadelphia and started engraving dies and seals ( Chamberlain 1954a, 590). Unfortunately, a U.S. embargo in response to British and French trade policies caused a depression beginning in 1808. Economic disruption, social unrest, and even threats of civil war ( Hickey 1989) marked Fürst's early years in America . In 1812, the year Fürst turned 30, friction between the U.S. and Britain led to war and the British Navy was soon threatening American coastal cities, including Fürst's adopted home of Philadelphia . In 1814 panic swept the country when the British succeeded in burning Washington ( Lord 1972, 215). Fürst can hardly have prospered during this turmoil. Ultimately, however, it was the War of 1812 that catapulted Fürst to prominence as a die engraver.

Congress voted some 27 medals to Army and Navy commanders during and following the war. By 1814 the Navy had begun to procure medals mandated for its officers. Reich was contracted for the work, but he completed only four dies (for two medals) by 1817, a clear indication that he would be unable to complete all of the needed dies ( Julian 1977, 147). This led the Navy to contract with Fürst to cut dies for the medal to Captain William Bainbridge . Meanwhile, Reich's eyesight deteriorated sufficiently to affect his work ( Witham 1993, 18, 19); his portrait die for Captain Stephen Decatur was not accepted by the Navy. Fürst was contracted to make a new portrait die and also made a new reverse after Reich's shattered while being hardened. After completing the Bainbridge and Decatur dies, Fürst wrote Navy Secretary Crowninshield asking that the Navy "make a regular contract with me for the other medals which remain to be executed" ( Witham 1993, 18). Whether or not he obtained such a comprehensive contract, Fürst ultimately did all the remaining medal dies for the Navy awards and then did all the dies for the Army awards. Creditable workmanship and the unavailability of Reich made Fürst the artist of choice for official medals. In 1817, in addition to working on the War of 1812 awards, Fürst engraved the Indian Peace Medal portraits of President James Monroe . He later did the Indian Peace Medal portraits for all the presidents through Van Buren .

Reich's disability caused Mint Director Robert Patterson to seek another assistant for Mint engraver Scot . An offer was made to Christian Gobrecht , which Gobrecht refused ( Taxay 1983, 109). Curiously, there is no evidence that Patterson gave any consideration to Fürst , who continued to make medal dies under contract to the War and Navy Departments. Perhaps these contractual obligations were too heavy to allow Fürst to work at the Mint; he had then only begun work on the dies for the War of 1812 medals, a project that would occupy him for some years. I believe it likely that Fürst also was not interested in the assistant's position at the smaller salary.

Scot died in late 1823. Fürst clearly believed that he was rightfully Scot's successor, but seems to have realized that he faced competition for the post. I have elsewhere suggested ( Neuzil 1991, 140) that Fürst engraved the dies for the Monroe presidential medal (medal 44 in the appendix) in an effort to promote himself for the engraver's position he had sought for so long. However, William Kneass was appointed the Mint's new engraver based on the recommendation of his personal friend, Chief Coiner Adam Eckfeldt ( Taxay 1983, 109). Compounding the injury to Fürst , Kneass's appointment roughly coincided with the end of Fürst's lucrative contracts for War of 1812 medal dies, which were essentially completed the following year. The fact that Fürst did not obtain the appointment as Mint engraver evidently incited him to petition the Congressional Committee on Claims for compensation. Asserting that he had been promised the position of Mint engraver before his arrival in 1807, Fürst asked the Committee for back pay (Proceedings n.d.). He explained the filing of his grievance 15 years after the fact by claiming unfamiliarity with American law and custom although in reality he may have been mollified by the income he enjoyed from the War of 1812 contracts. The petition was rejected, allegedly because no written record existed of Appleton's original offer (Proceedings n.d.).

In 1835 Kneass suffered a stroke. Gobrecht this time accepted the assistant's position ( Taxay 1983, 171), and when Kneass died in 1840, assumed the mantle of engraver. Probably seeing himself in direct competition with Fürst , Gobrecht had actively promoted himself for the engraver's position ( Breen 1988, 433). Fürst , by then in his late fifties, returned to Europe .

Although Gobrecht's appointment probably was the immediate reason for Fürst's return to Europe , other factors probably contributed to his decision to leave. Fürst's government contracts had dwindled to the point that his official work was limited to the infrequent Indian Peace Medal dies for new presidents. Even the income from these infrequent contracts was at risk. The nature of medal making and the role of medals themselves were changing fundamentally in the late 1830s. The Contamin portrait lathe, purchased by the Mint in 1836, could mechanically reduce bas-relief models to make dies ( Taxay 1983, 150). The new process was much less expensive than hand-engraving, and threatened to make die engraving by hand obsolete. 2 Presaging an even more fundamental change, photography was becoming practical ( Dibner 1967, 461) and promised an alternative to medallic and other forms of miniature portraiture. Fürst would certainly have seen these changes as threats to his livelihood.

Perhaps the Old World offered Fürst some respite from the forward march of technology. Following his return to Europe , Fürst continued to hand-engrave medal dies for some years. Forrer (1904, 7:333) lists a medallist under the name " Fürst " who was active in Munich, Germany , from 1841 to 1847. We can surmise that this was Moritz Fürst because of a German medal dated 1841 and signed with the same letter punches Fürst used in America ( Figure 2 ). Forrer's listing implies that Fürst engraved dies until about the age of 65. Nothing more is known of this phase of Fürst's life.

A die census presented in the appendix (Table 2) reveals that Fürst made more American medal dies than previously realized. Slightly over 100 dies can be identified that are attributable to Fürst while he was in America . However, as discussed in the appendix, it is quite likely that the actual total is larger, perhaps 113 or even more.

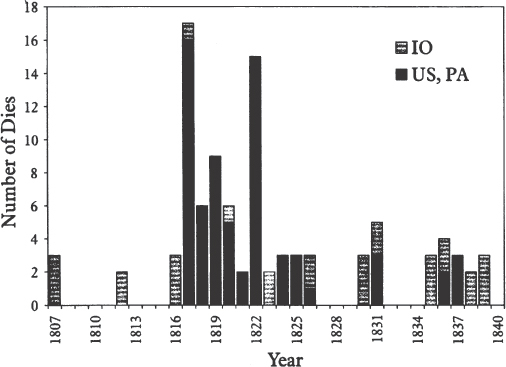

When the date of completion of a die is known or can be reasonably constrained, it has been noted in Table 2 ( Julian (1977) and other authorities noted in Table 2 are the source of most of the dates). The availability of dates for most of the dies presents the possibility of examining Fürst's die-making activity in a quantitative fashion. Using the information in Table 2, I have plotted by year the number of dies Fürst produced in Figure 3 . This plot shows 97 dies; it does not include seven for which the dates of completion are very uncertain, nor does it include any of several unverified dies from Table 2. When interpreting the plot, one should bear in mind that some of the completion dates are somewhat uncertain.

Fig. 3. Plot showing the number of medal dies Fürst produced, by year. The plot breaks down Fürst's production into official (US and PA) and unofficial (IO) dies (see the Appendix for a fuller explanation of these categories and identification of the dies). Replacement dies for US-24, 40, 50, and 54 are included in the plot, but dies IO-2, 8, 9, 15, 16, 27, and 30 are not included because of uncertain completion dates. Where a range of years is given in Table 2, the latest date was used, except for dies US-43, 47, 54, and 60 for which the earliest date was used.

Figure 3 shows that Fürst's die-making fluctuated dramatically, with most of the activity after 1816 and before 1823. It was during these middle years that he executed dies for the Navy and Army awards of the War of 1812 (denoted as US and PA dies in Figure 3 and Table 2). The Navy awards were his dominant activity from 1817 through 1820. The Army awards, nearly all of which were done during 1821 through 1824, account for the second prominent peak in 1822. The plot implies that in 1817 he made 17 dies (including replacements of three dies that broke during hardening), an average of one die every three weeks. The year 1822 is shown being nearly as busy, with 15 dies (counting one replacement die). 3 Between the beginning of 1817 and the end of 1824 the count is at least 58 dies (including replacements), an average of more than 7 dies per year. This eight-year stretch, roughly one fourth of Fürst's time in America , accounts for over half of Fürst's known output of medal dies. In contrast, the years before 1817 and after 1825 are distinguished by both lower overall rates of die production and production of most of Fürst's unofficial or nongovernment dies (denoted as IO in Figure 3 and Table 2).

Payments cited by Julian (1977) suggest that Fürst typically received between $300 and $400 per die. The amount varied according to the difficulty of the die and other expenses involved. Interestingly, Fürst asked more for battle scenes than for portraits, presumably reflecting the engraving time required. Probably included in the fees were the cost of materials, polishing the dies after hardening (Proceedings n.d.) and, in some cases, travel in order to make portrait sketches. Assuming that Fürst completed about 100 dies that actually provided income, 4 his fees from this activity were in the neighborhood of $35,000 over about 33 years, or close to an average of $1,000 per year. During 1817 through 1824, the busy middle years of his career, Fürst's annual fees from diemaking averaged, by this analysis, between $2,000 and $3,000. By comparison, Reich's average annual income from 1800 to 1817 is estimated to have been about $700 ( Witham 1993, 46). 5

Reliable data on wages and income are sparse for this period, but it appears that in 1830 wages to laborers were about $0.75 to $1.00 per day while craftsmen and land-owning farmers had incomes of about $1.00 to $1.50 per day ( Larkin 1979, 2; Kuiken 1997). Fürst's income from a single die thus exceeded a laborer's earnings for a year, and his average annual income between 1817 and 1824 was nearly ten times that amount. Fürst also had income, which may have been significant, from other activities (see next section). All told, he enjoyed a rather substantial, although unsteady, income. However, even during his most active years, Fürst reportedly lived beyond his means. Referring to the period 1821-23, Julian (1977, 112) states that Fürst "apparently spent his funds far faster than they were received, thus fitting the classical mold of the impoverished artist. He was, nearly always, deeply in debt." The loss of the income from the War of 1812 dies, beginning in 1825, must have been financially devastating to Fürst after eight years of relatively high income. This was undoubtedly the impetus behind Fürst's petition to the Committee on Claims and publication of the pamphlet detailing the claim (Proceedings n.d.) after it was rejected.

Chamberlain (1954a, 590) and Albert (1974) have reported that Fürst engraved seals and at least one die for uniform buttons. However, the fact that Fürst also engraved dies for decorative embellishments on silverware is largely unrecognized by numismatists. At the turn of the eighteenth century, the making of silverware was evolving toward increasing mechanization, allowing cheaper and more rapid fabrication ( Plaut n.d., 7). Before this, silversmiths cast or engraved the ornamentation for silverware. Die-struck embellishments were easier to produce in quantity and often more elaborate and expressive than engraved or cast ornamentation. This presented opportunities for die-sinkers like Fürst to make and sell die-struck ornamentation or dies themselves to makers of silverware.

I have identified five dies by Fürst that were used for making decorative embellishments, all made before 1817. Fürst probably did not make decorative dies and similar items after he became busy with the War of 1812 dies in 1817. Whether he made decorative dies after 1824, when he had largely completed the War of 1812 contracts, is not known. It is also unclear whether Fürst sold the decorative dies themselves, or sold the embellishments that he made from them.

Fürst's known decorative dies are of two types. The simplest was a cylinder die with a repeating grapevine pattern that produced a decorative silver strip. Fürst signed the die, and his signature appears about every 15.7 cm along the strip ( Skerry 1986), indicating that the cylinder had a diameter of approximately 5 cm. Decorative silver strips from this signed die were incorporated into a tea service now at the Yale Museum of Decorative Arts in New Haven, Connecticut ( Figure 4 ) and a ewer now at the Winterthur Museum in Wilmington, Delaware . These pieces have been dated to between 1810 and 1817 (Yale University Art Gallery 1984). Decorative strips from the same die also appear on a silver tea service dated to circa 1835 ( Christie's 1988, 40).

Decorative dies of the second type were used to impress designs on square silver panels or sheets. The panels were applied to flat surfaces on silverware. Fürst cut at least four such dies, comprised of two different compositions in large (56 by 56 mm) and small (34 by 34 mm) versions. One design features Zeus as an eagle tended by his daughter Hebe ( Figure 5 ) and the other is a classically-garbed female leaning on a rock. Panels struck from these dies were used to decorate a silver tea service ( Figure 6 ), made in New York about 1810 ( Southeby's 1985), that is now in a private collection. The panels are not fastened, but slide into slots on the sides of the pieces.

Fig. 4. Silver tea service incorporating a decorative strip with a grape vine motif from a cylinder-die engraved by Fürst (the decorative strip on the coffee pot, second from left, is by a different engraver). Attributed to John Armstrong or Allen Armstrong , ca. 1810-1817 (coffee pot by William Thompson , ca. 1831). Photo: Yale University Art Gallery, Josephine Setze Fund for the John Marshall Phillips Collection.

Fig. 5. Drawing of decorative silver panel from a die engraved by Fürst . This is one of two panel designs, each in two sizes, incorporated into a silver tea service attributed to Hugh Wishart , New York, ca . 1810.

Because the decorative dies carry classical or purely decorative motifs, they cannot clearly be assigned an American origin. The embellishments first appear on American silverware dated between 1810 and 1817, and it is possible that Fürst cut the dies before coming to America . However, I believe it likely that Fürst made the dies after coming to America , and probably while establishing his engraving business in Philadelphia .

Other decorative dies by Fürst may exist. Chamberlain (1954a, 592) reports that Fürst made presentation swords under contract to the State of New York for several War of 1812 commanders. Fürst may have engraved dies to produce decorative elements for these swords and their scabbards.

The allegorical and classical figures on Fürst's medals and embellishments suggest that he could have made significant contributions to the nation's coinage, which used classical figures as embodiments of liberty . Although Fürst never got the chance to design coins as a Mint engraver, it is possible that he did at least influence U.S. coin design. Figure 7 , reproduced from Taxay (1983, 172), shows preliminary designs by William Kneass , Titian Peale , and Thomas Sully for the new seated Liberty coinage. These sketches, dating to 1835, clearly borrow from many earlier coins, including English and pre-Federal American issues that feature seated goddesses or allegorical female figures. For example, the late eighteenth-century coppers of Vermont and Connecticut crudely portray a seated female figure with a shield and liberty cap on a pole. However, the most direct and immediate precedent for the sketches appears to be a medal by Fürst . Figure 8 shows an American Institute medal from a die (IO-25 in Table 2) made by Fürst in about 1830 ( Harkness 1989, 128), some five years before the designs in Figure 7 . Fürst's composition features a seated, classically-garbed female holding a liberty cap on a pole and supporting a shield, all of which are major elements in the designs that were ultimately adapted to make the new U.S. coinage.

Fig. 7. Sketches by William Kneass (left) and Thomas Sully (right) and painting by Titian Peale (center) showing design concepts for the "seated liberty" coinage. Reproduced from Taxay (1983, 172).

Additional examples of coin designs that may have borrowed from Fürst's American Institute medal ( Figure 8 ) are the 1859 pattern double eagle by Paquet and 1873 pattern trade dollars by Barber . The Paquet double eagle ( Figure 9 ) has the seated Liberty with arm outstretched, a U.S. shield, and an eagle posed very much like that on Fürst's composition. The trade dollar ( Figure 10 ) features a seated Liberty holding a pole and liberty cap, with a distant sea before her and a plow and sheaf of wheat behind her. All of these elements appear on the American Institute medal.

Fig. 9. Pattern for a gold double eagle by Paquet , dated 1859 and catalogued as Judd no. 257. Reproduced from Judd (1982, 61).

Fig. 10. Pattern for a trade dollar by Barber , dated 1873 and catalogued as Judd no. 1290. Several trade dollar patterns ( Judd nos. 1290-1306) bear a similar design. Reproduced from Judd (1982, 147).

In considering the possible link between the American Institute medal and later coin designs it is worth noting that Fürst's American Institute design proved quite popular. It was copied repeatedly (by engravers such as Robert Lovett , Jr. and George H. Lovett ) on later dies for the American Institute, appearing on medals until about the turn of the century ( Harkness 1989, 132). The design also could be found in nineteenth century print advertisements and even on a hard-times token ( Figure 11 ), attesting to its wide popularity.

In terms of design, Fürst's medals are a mixed bag of his own and others' work. Most of his dies for War of 1812 Congressional awards copied portraits, battle scenes and allegorical scenes by graphic artists, both obscure and well known. Reverses for many of the Army medals, for example, were designed by the painter Thomas Sully ( Julian 1977, 112). Other dies, most notably the Indian Peace Medal portraits, were composed as well as engraved by Fürst . The presidential portraits on the Peace Medals are especially noteworthy and valuable as they were based on Fürst's life studies of these men (see, for example, Prucha 1971, 101-103).

Marvin Sadik , writing in 1977 as Director of the National Portrait Gallery ( Sadik 1977, 9),

described Fürst's contribution to American medallic art by referring to his "brilliant series of twenty six

[medals] for the military heroes of the War of 1812." He went on to state that: [i] n the sustained excellence evident in the work

of Reich and Fürst , which forms another link in the great tradition established by

Pisanello , one sees a worthy continuation of the high standards set for American medallic art by the trio

of Frenchmen [ Duvivier, Dupre , and Gatteaux ] who produced our earliest medals.

A less enthusiastic evaluation was provided by Vermeule (1971, 39) in his book Numismatic Art in America . Vermeule mentions Fürst once in passing, referring to the "Napoleonic pictorialism and patriotic fussiness of Reich and Fürst ."

However one views Fürst's work, there is no denying that his prolific output of dies made him the leading figure in American medallic art of the early nineteenth century. Medals from most of Fürst's dies, including all of the War of 1812 and Indian Peace series, have been restruck and avidly collected since the mid-nineteenth century. 6 Many, in fact, continue to be periodically restruck from copy dies and sold by the U.S. Mint as part of a series of "national" medals ( Failor and Hayden 1972). His dominance of early nineteenth century medallic art in America has not brought Fürst a corresponding level of recognition in American numismatic circles. I hope that the information presented here will provide a framework for the fuller study that Fürst deserves.

I am grateful to the many individuals who helped me locate and better understand Fürst's medals. It is impossible to thank everyone, but several individuals deserve special mention. They include Paul Bosco, Carl Carlson, Jim Cheevers (USNA Museum), Sim Comfort, Chris Eimer, Norm Flayderman, John Ford , Jr., Daniel Friedenberg, Andy Harkness, Bob Julian, Patricia Kane (Yale University Art Gallery), Charles Kirtley, Richard Margolis, Charles McSorley , the late Lester Merkin, Gene Neuzil, Heather Palmer ( Decatur House Museum), Alan Weinberg, Frank White ( Old Sturbridge Village Museum), and the late Stew Witham . Particular thanks go to Alan Stahl and the American Numismatic Society for providing a forum for a long overdue reexamination of Moritz Fürst , and to Joe Levine and Mike Hodder for critical reviews of the manuscript. Errors of fact or interpretation remain my responsibility.

Ninety-two medal dies can be definitely attributed to Fürst during his American period, but a strong case can be made that the actual number is over 100 and possibly as many as 113 or more. 7 Uncertainty in the die count results from problems of attribution and the likelihood that Fürst made some dies that are presently lost. Sixty-one different medals (not including sporadic mulings) are known to have been struck from the dies.

This appendix presents both a tabulated census of the dies and an illustrated catalogue of medals from the dies. The compilation includes several medals (representing 16 individual dies), that were not included in Chamberlain's (1954b) catalogue of Fürst's work.

Table 2 tallies all American medal dies that can be attributed to Fürst . The tabulation is based on my own observations as well as published and other authoritative sources as cited. The presentation of the dies is not chronological because their exact sequence (as opposed to their year of completion) is poorly known. Rather, the dies are arranged in four broad generic categories. First are dies done under contract to the United States (designated by US -numbers), comprised of presidential portrait dies for the Indian Peace Medal series and Congressionally-mandated award medals for the War of 1812. Indian Peace Medal dies and Army Congressional award dies were made under contract to the War Department whereas Navy Congressional award dies were made under contract to the Navy Department. Second are dies for medals mandated by the Pennsylvania legislature and made under contract to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (designated by PA ) as awards for the Battle of Lake Erie in the War of 1812. Listed third are dies made for individuals, organizations, and as speculative ventures (designated by IO). Dies for individuals (such as IO-17 and 18) and organizations (such as IO-25 and 26) were private commissions. Other dies (such as IO-6 and 7) apparently were ventures intended by Fürst for striking medals to be sold for profit. 8 The fourth and last category in Table 2 comprises dies whose existence is speculative (designated by UV, indicating "unverified"); these are dies for which there is only indirect evidence (i.e. there is a written description, reference, or such, but no known medal from the die or die itself).

Attribution . Fürst signed nearly all of the tabulated dies (generally using letter punches 9 ), leaving no question as to their authorship. Fürst indicated his authorship in various ways, ranging from an explicit statement ( FURST DESIGNED AND SCULP, on die IO-5; see medal 44) to simply his name ( FURST or FURST F. ) or, on some dies, only the initial F. Eight dies included in Table 2 are unsigned (PA-3, 4, IO-1, 2, 24, 26, 27, 30). For most of these, I have relied on comparisons of engraving style or letter punches to attribute them to Fürst . The exception is die IO-2 ( John Adams ; medal 42), which is linked to Fürst anectdotally, as I describe in more detail below. Although attribution is never certain for unsigned dies, there is little question that most of the unsigned dies in Table 2 were engraved by Fürst . Why didn't Fürst sign them? Some dies, such as inscription die IO-24 (medal 55) and wreath dies IO-26, 27, 30 (medals 56 and 58), probably had too little space or were simple enough that Fürst declined to sign them. In the case of other dies (PA-3,4, IO-1,2; medals 40, 41 and 42) the lack of a signature is perplexing.

The die memorializing Washington (IO-1; medal 41) is especially interesting with regard to the problem of attribution. This unsigned die, almost certainly by Fürst , features a bust of Washington on a pedestal flanked by figures representing an Indian and a classical female. It exhibits several strong stylistic links to Fürst's known dies. The modelling of the human figures, especially their musculature and feet, is quite characteristic of Fürst's work. The stance of the Indian closely matches that of a figure on die US-20, the reverse of the Congressional award to William Henry Harrison (medal 16), and the rendering of the tree branches on the pedestal matches that on die IO-11, one of the reverses of the Benjamin Rush medals (see medal 47). Attribution of this die to Fürst resolves a longstanding problem. Chamberlain (1954b, 937) noted that an art exhibit in Philadelphia in 1817 listed a medal of Washington by Fürst and added that the medal was unknown to her. Apparently medal no. 41 (die IO-1) is the medal in question.

Die IO-2 (see medal 42), an unsigned portrait die of John Adams , is atypical of Fürst's work,

the bust being rather stiff and not particularly natural. Differences are apparent, for example, with Fürst's more

lifelike portrayal of Adams's son, John Quincy Adams , on Indian Peace Medal

dies US-4, 5, 6 (medals 4, 5, 6). However, as Julian (1977, 31) notes, both Franklin Peale and

J.R. Snowden explicitly attributed the die to Fürst . Peale was the

Mint's Chief Coiner from 1839 to 1854 and Snowden was Director from 1853 to 1861. Peale

was associated with the Mint before 1839 and thus probably had first-hand knowledge of

Fürst's work, lending credence to his attribution. Contrary evidence comes from an 1871 auction sale (

Bangs, Merwin 1871, 69) of the collection of William F. Packer , a former

Pennsylvania governor who died in 1870. The sale contained a John Adams medal (of the

correct diameter for IO-2) with the cataloguer's note: I find the following memorandum in regard to this Medal in the handwriting of

the late Governor Packer:

During the Presidency of the Elder Adams , the die for this medal was cut and

submitted to the government, but not accepted. The few Medals struck - some four or five in number - have remained in the

possesion

of the artist's family until very recently.

The emphasis is mine. If the die was cut during the elder Adams's presidency, which ended in 1801, it could not have been done by Fürst (but could have been done by Mint engraver Robert Scot ). Thus, the attribution of die IO-2 to Fürst is uncertain. If Fürst did engrave IO-2, the style must echo that of an earlier portrait, perhaps a painting, that served as the model.

A number of questions surround the dies for the naval award medals authorized by the Pennsylvania legislature. Two of the four dies apparently used to strike the original medals are unsigned. Fürst signed dies PA-1 and PA-2 (medal 39) but the unsigned dies PA-3 and PA-4 (medal 40) also appear to be his work. The unsigned portrait die of Captain Oliver H. Perry (PA-3) is a matter of curiosity because it features a different rendering of Perry than the signed die but carries the same legends in the same arrangement. It is very typical of Fürst's style. Likewise, the rendering of the boughs tied with a ribbon on PA-4 is quite reminiscent of the design on die US-32, Fürst's signed reverse of the Congressional award to Winfield Scott (medal 22). I believe that both of the unsigned dies (PA-3 and PA-4, medal 40) are by Fürst .

Unsigned dies IO-26, 27, and 30 are comprised of relatively simple wreath designs used as the reverses on award medals presented by the American Institute and the Mechanics Institute (medals 56 and 58). The two organizations shared at least one reverse die (IO-27), which is found paired with both obverse dies (IO-25 and IO-29). Die IO-26 is apparently the earliest reverse and clearly seems to be Fürst's work. The wreath of boughs tied with a bow is also quite similar to the wreath on the reverse of the Winfield Scott medal (medal 22). IO-27 is a later die, but stylistically similar and probably also by Fürst . The authorship of IO-30, a still later reverse die, is questionable. Unlike the oak leaves on IO-26 and 27, which were made with a punch, those on IO-30 are individually engraved. Die IO-30 is quite possibly the work of another engraver copying Fürst's original design.

Problems of attribution extend to the provenance of the dies. My intent is to include only "American" medal dies in the tabulation, that is, dies made by Fürst while he was in America . Fürst may have engraved medal dies before coming to America and he certainly did so after returning to Europe (see main text). In most cases the dies in Table 2 are clearly from his American period, but for a few (dies IO-31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36) an American origin is disputable because foreign subjects or interests are represented. Inclusion of these dies in Table 2 reflects the fact that they appear to date from Fürst's American period. They may represent commissions from foreign interests, perhaps diplomatic or trade missions, that were in the United States at the time.

Intended Die Pairings. The intended pairing is firmly established for most of Fürst's dies, and is indicated in Table 2. For example, although the dies for the Army medals of the War of 1812 were muled extensively at the Mint during the latter half of the nineteenth century, the intended pairing for these dies is well documented (even if it is not always self-evident). In a few instances, however, dies appear to have been muled so consistently that the mulings have come to be accepted as the intended pairings. In other cases, it is not clear what the intended pairing was or, indeed, whether mate dies ever existed.

The confusion surrounding the Pennsylvania Naval award dies (PA-1, 2, 3, 4; medals 39 and 40) extends to their intended pairings. Julian (1977, 166) catalogues four medals representing all possible obversereverse combinations of the two obverse with the two reverse dies. However, Julian also states that Fürst engraved only one obverse and two reverse dies for the Pennsylvania medals. Adding to the confusion is the fact that the signed obverse die (PA-1; medal 39) is known only from two gold medals in institutional collections where it is paired with signed reverse die PA-2: I know of no other confirmed pairings for PA-1 (including the pairing with PA-4 that Julian speculatively catalogues). The Pennsylvania legislature authorized gold medals for Captain Perry , Master Commandant Elliot , and a Lieutenant John J. Yarnall , and silver medals of a distinct design for Pennsylvania citizens who served in the enlisted ranks in the Battle of Lake Erie ( Ayers 1972, 7). Perhaps the signed obverse was intended to be paired with both reverses for the two different awards. If so, how does one explain the unsigned obverse? The signed obverse die may have failed or had to be retired after a few uses, explaining the lack of restrikes from it and the need for a second portrait die. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that the signed obverse was already buckled when Perry's gold medal was struck. Additional confusion about die pairing probably arose because unsigned obverse die PA-3 was extensively paired with signed reverse die PA-2 by the Mint to make restrikes in the late nineteenth century.

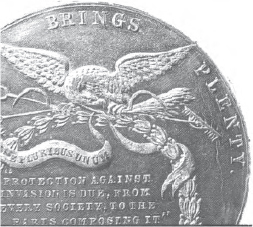

Fürst's unofficial die portraying President Madison (IO-3) has been extensively muled. This die, paired with an unsigned reverse die, was used to strike medals (number 43) in the 1860s or earlier. 10 This pairing is the only one known for IO-3 and has come to be accepted by many as the intended one. However, multiple lines of evidence indicate that it is a mule. First, stylistic comparisons clearly indicate that the reverse die is not by Fürst . Second, the legend within the wreath, which refers to political issues during the War of 1812, is incompatible with the surrounding legend INDUSTRY BRINGS PLENTY. The design itself, which features agricultural implements, is at odds with the central inscription. 11 Third, the reverse die was reduced from a larger diameter to one matching that of IO-3. The reduction is apparent from the position of the eagle's wingtips, which extend through the border to the edge of the die ( Figure A1 ). Reduction is also indicated by prior cracking of the die below the word PLENTY, which caused that lettering to be especially close to the new edge ( Figure A1 ). Finally, by the time known medals were struck, the obverse die (IO-3) had been crudely lapped to conceal damage. The lapping obliterated part of Fürst's name on the banner below the bust. All of these observations lead to the conclusion that the reverse die used with IO-3 was not its intended mate, but was concocted to permit restriking the Madison portrait from an impaired die. The intended pairing for die IO-3 is thus unknown.

The John Adams "Indian Peace Medal" (medal no. 42, which uses unsigned portrait die IO-2) is also, strictly speaking, a mule. It is not a true Indian Peace Medal because the Reich Peace and Friendship reverse was made in 1809 ( Julian 1977, 29), well after Adams held office. Mint Director J. R. Snowden considered the John Adams portrait die to be a private commission and noted the absence of a reverse ( Prucha 1971, 137). The intended pairing is thus uncertain.

Fig. A1. Detail of reverse die used with Fürst's Madison portrait die (IO-3). As seen here, (1) the eagle's wingtip extends through the border to the edge of the die and (2) the word PLENTY, with tangential cracks beneath it, is closer to the edge than BRINGS. Both observations indicate that the die was once larger and was reduced to mate with IO-3.

Two of Fürst's dies are known only from uniface medals. The dies portraying George Washington (IO-1; medal 41) and Gershom Seixas (IO-19; medal 52) are not known to have been paired with any die ( Stack's 1996, 40; Friedenberg 1990). It is possible that no mates were ever made for these dies. This is implied for the Washington die by an entry in an 1817 art exhibit catalogue (cited by Chamberlain 1954b, 937) that mentions the Washington portrait but does not mention a reverse.

Missing dies. Various lines of evidence suggest that I have not identified all of Fürst's American medal dies. First, as shown by Figure 3 in the main text, relatively few dies are known from the early and late portions of Fürst's American career; he had ample time to produce more dies than are now documented. Second, some of Fürst's dies are known to us through only one, two, or a few medals. In particular, dies that Fürst made as speculative ventures typically left few surviving medals. Apparently, if sufficient subscriptions were not obtained, a medal would not be struck in large quantities, or not struck at all. This may explain the rarity of medals from the Washington (IO-1; medal 41), Monroe (IO-4, 5; medal 44), and John Q. Adams inaugural (IO-6, 7; medal 45) dies, and the lack of original strikings from the Madison (IO-3; medal 43) and Seixas (IO-19; medal 52) dies. 12 These medals could easily have been lost to posterity and, by extension, it would not be surprising if others have in fact been lost. Third, indirect evidence exists for several specific dies that are currently unknown. Nine candidates for such missing dies are listed in Table 2 as "unverified" (UV).

The listings of UV-1 and 2 and UV-3 and 4 are prompted by exhibit catalogues of 1811 and 1829 cited by Chamberlain (1954b, 937). The first refers to "a medal of William Penn ," which is unknown today. The second lists a "Cast of a medal of President Andrew Jackson , on reverse the Battle of New Orleans ." Unlike the Congressional award to Jackson (dies US-21, 22; medal 17), which features an allegorical scene on the reverse, the catalogue explicitly refers to a depiction of the battle. No such medal is known today. 13 The word cast in the catalogue entry suggests a trial impression rather than a struck medal; perhaps no struck medals were made.

The unverified die depicting Captain Jesse Elliot's capture of the British ships Detroit and Caledonia (UV-5) is listed based on an unusual piece of evidence. Chamberlain (1954b, 938) located and reproduced an early nineteenth century painting that appears to depict two different gold medals awarded to Captain Jesse Elliot ( Figure A2 ). The obverse of the Congressional award (die US-46) is shown together with its intended reverse depicting the Battle of Lake Erie (die US-56) to the left and in the center of Figure A2 . However, an undocumented reverse (die UV-5) is also shown, as seen on the right in Figure A2 . Reverse die UV-5 may have been mated with the regular portrait obverse for striking an award medal for Elliot from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania .

I also considered mateless dies to be evidence for missing dies. The Madison obverse die (IO-3), which is known only from mulings with an unrelated reverse die, is a good example. Did Fürst make a reverse die, now missing, to pair with IO-3? I believe it likely because he cut an elaborate reverse die (IO-5) for a similar portrait die of Monroe (IO-4; see medal 44). Dies that are now missing may also have served as reverses for the Washington (IO-1), John Adams (IO-2), and Gershom Seixas (IO-19) portrait dies, as indicated in Table 2.

Damage to the dies, when present, is noted under "Comments" in Table 2. Notes on damage are based on personal examination of many medals. Table 2 reveals a surprising fact with respect to Fürst's official (US and PA) dies: most of the dies for the Navy awards exhibit some sort of damage, whereas few of the Army or Indian Peace Medal dies do. More than 60% (17/28) of the Naval dies exhibit damage (or had to be replaced), whereas this is true of fewer than 10% of the Army dies (2/22) and the Indian Peace Medal dies (1/12). The damage to the Naval dies is usually buckling and cracks. The buckling occurs as a "sinking" of the die that causes it to become mildly concave and the field of the struck medal to be correspondingly convex. The sinking is generally uneven and cracks are often located along the trace of maximum buckling. Other types of damage evident on the Naval dies include stray cracks and indentations and even corrosion that may have occurred during acid "frosting" of the relief. 14

Fig. A2. Detail of contemporary painting by John A. Woodside that appears to depict two different gold medals awarded to Navy Captain Jesse D. Elliot . Reproduced from Chamberlain (1954b, 938).

Apparently, most of the damage occurred during the initial handling and hardening of the dies, rather than developing later in the die's life (although the damage often worsened with use). This can be established because the Naval award dies were used in a very consistent manner: first a single gold medal was struck for the honoree, and then a limited number of silver medals were struck for his officers ( Julian 1977, xxii; 3 gold medals were struck in the case of the Pennsylvania award to Perry ). Original gold and silver medals therefore display very early die states. In examining several original gold and silver award medals from the Naval series, I have found that damage known from copper restrikes of the medals generally is also present on the original gold and silver strikings. The gold medal presented to Captain Oliver H. Perry by Pennsylvania and now in the collection of the U.S. Naval Academy is an excellent example; this medal was presumably the first struck and shows that both dies were strongly buckled.

Buckling and cracks occurred during hardening of the die ( Julian 1977, 152), which required heating and rapid cooling by quenching in water ( Taxay 1983, 83; Landis , 1997). In several instances (US-24, 35, 49, 50, 52, 54), Julian cites contemporary documents that mention damage caused by hardening. Other types of damage, such as stray indentations, were apparently due to careless handling before hardening.

Why did the Naval dies suffer more damage than the Army and the Peace Medal dies? They were the first large group of medal dies to be delivered to the Mint for hardening and striking, and inexperience with such large dies may have led to problems. Prior to the large influx of Naval War of 1812 dies, Mint personnel had worked mostly with small coinage dies. Julian (1977, 113) reports that Adam Eckfeldt , the Mint's Chief Coiner, was often very slow to harden medal dies. Risk of damage to the dies may have caused Eckfeldt to adopt a very deliberate approach to hardening. By the time the Army award dies and most of the Indian Peace medal dies were delivered to the Mint , Eckfeldt had more experience with the quirks of large medal dies. It is also conceivable that the War Department (which contracted for both the Army's War of 1812 dies and the Indian Peace Medal dies) procured superior steel for its dies.

| Julian Number | This Catalogue | Julian Number | This Catalogue |

| IP-1 | 42 | MI-20 | 22 |

| IP-8 | 1 | MI-21 | 23 |

| IP-9 | 2 | NA-4 | 24 |

| IP-10 | 3 | NA-5 | 25 |

| IP-11 | 4 | NA-6 | 26 |

| IP-12 | 5 | NA-7 | 27 |

| IP-13 | 6 | NA-8 | 28 |

| IP-14 | 7 | NA-9 | 29 |

| IP-15 | 8 | NA-10 | 30 |

| IP-16 | 9 | NA-11 | 31 |

| IP-17 | 10 | NA-13 | 32 |

| IP-18 | 11 | NA-14 | 33 |

| IP-19 | 12 | NA-15 | 34 |

| IP-20 | mule (see 16) | NA-16 | 35 |

| PR-3 | 43 | NA-17 | 36 |

| PR-4 | 44 | NA-18 | mule (see 39, 40) |

| PR-5 | 45 | NA-19 | 40 |

| PR-6 | mule (see 11) | Na-20 | 39 |

| MI-11 | 13 | NA-21 | mule (see 40, 39) |

| MI-12 | 14 | NA-22 | 37 |

| MI-13 | 15 | NA-23 | 38 |

| MI-14 | 16 | MT-18 | 54 |

| MI-15 | 17 | MT-24 | 46 |

| MI-16 | 18 | PE-15 | 53 |

| MI-17 | 19 | PE-30 | 47 |

| MI-18 | 20 | PE-31 | 48 |

| MI-19 | 21 | AM-1 | 55 |

| Die No. | Description | Yr. a | Size (mm) | Pr. b | Cat. No. | Comments |

| Dies Under Contract to U. S. | ||||||

| Indian Peace Medals | ||||||

| US-1 | James Monroe | 1819 | 76 | (a) | 1 | |

| US-2 | James Monroe | 1819 | 62 | (b) | 2 | |

| US-3 | James Monroe | 1819 | 51 | (c) | 3 | |

| US-4 | John Quincy Adams | 1825 | 76 | (a) | 4 | Buckled and cracked during hardening; lapping to repair buckling noted on original silver medals and later copper restrike medals as weakening of lettering left of bust. |

| US-5 | John Quincy Adams | 1825 | 62 | (b) | 5 | |

| US-6 | John Quincy Adams | 1825 | 51 | (c) | 6 | |

| US-7 | Andrew Jackson | 1831 | 76 | (a) | 7 | |

| US-8 | Andrew Jackson | 1831 | 62 | (b) | 8 | |

| US-9 | Andrew Jackson | 1831 | 51 | (c) | 9 | |

| US-10 | Martin Van Buren | 1837 | 76 | (a) | 10 | |

| US-11 | Martin Van Buren | 1837 | 62 | (b) | 11 | |

| US-12 | Martin Van Buren | 1837 | 51 | (c) | 12 | |

| Congressional Awards - Army | ||||||

| US-13 | Jacob Brown | 1822(?) | 65 | ↓ | 13 | |

| US-14 | Battles of Chippewa, Niagara, and Erie : Allegorical scene I | 1822(?) | 65 | ↑ | 13 | |

| US-15 | George Croghan | 1836(?) | 65 | ↓ | 14 | Cracked through bust (during hardening?) as noted on copper restrike medals. Extensive die rust also noted, but only on late copper restrikes. |

| US-16 | Battle of Sandusky | 1836(?) | 65 | ↑ | 14 | |

| US-17 | Edmund P. Gaines | 1822 | 65 | ↓ | 15 | |

| US-18 | Battle of Erie | 1822 | 65 | ↑ | 15 | |

| US-19 | William H. Harrison | 1821 | 65 | ↓ | 16 | Also used at Mint to strike ersatz Indian Peace Medal listed by Julian (1977, 45) as IP-20. |

| US-20 | Battle of the Thames : Allegorical scene | by 1824 | 65 | ↑ | 16 | |

| US-21 | Andrew Jackson | 1822(?) | 65 | ↓ | 17 | |

| US-22 | Battle of New Orleans : Allegorical scene | 1822(?) | 65 | ↑ | 17 | |

| US-23 | Alexander Macomb | 1822 | 65 | ↓ | 18 | |

| US-24 | Battle of Plattsburgh | 1822 | 65 | ↑ | 18 | Original die broken during hardening; replacement made by Fürst ( Julian 1977, 128). |

| US-25 | James Miller | between 1821 and 1824 | 65 | ↓ | 19 | |

| US-26 | Battles of Chippewa, Niagara,and Erie : Allegorical scene II | between 1821 and 1824 | 65 | ↑ | 19 | |

| US-27 | Peter B. Porter | 1822(?) | 65 | ↓ | 20 | |

| US-28 | Battles of Chippewa, Niagara, and Erie : Allegorical scene III | 1822(?) | 65 | ↑ | 20 | |

| US-29 | Eleazer W. Ripley | 1826 | 65 | ↓ | 21 | |

| US-30 | Battles of Chippewa, Niagara, and Erie : Allegorical scene IV | 1821 | 65 | ↑ | 21 | |

| US-31 | Winfield Scott | 1822 | 65 | ↓ | 22 | |

| US-32 | Battles of Chippewa and Niagara : Wreath & Inscription | 1822 | 65 | ↑ | 22 | |

| US-33 | Isaac Shelby | 1822 | 65 | ↓ | 23 | |

| US-34 | Battle of the Thames | 1822 | 65 | ↑ | 23 | |

| Congressional Awards - Navy | ||||||

| US-35 | William Bainbridge | 1817 | 65 | ↓ | 24 | Buckled during hardening, but repaired (lapped?) by Adam Eckfeldt ( Julian 1977, 152). No die damage apparent on medals. |

| US-36 | Constitution - Java engagement | 1817 | 65 | ↑ | 24 | |

| US-37 | James Biddle | 1819 | 65 | ↓ | 25 | |

| US-38 | Hornet - Penguin engagement | 1819 | 65 | ↑ | 25 | Small crack through first S in SERVICES and stray indentations in die noted on named original silver medal. |

| US-39 | Johnston Blakely | 1820(?) | 65 | ↓ | 26 | |

| US-40 | Wasp - Reindeer engagement | 1820(?) | 65 | ↑ | 26 | Corrosion damage (from acid pickling?), most visible on left side in ocean waves, noted on original silver medal. |

| US-41 | William Burrows (funeral urn) | before 1821 | 65 | ↓ | 27 | Buckled and cracked (during hardening?) as noted on copper restrike medals. |

| US-42 | Enterprize - Boxer engagement | before 1821 | 65 | ↑ | 27, 35 | |

| US-43 | Stephen Cassin | 1818 or later | 65 | US-53 | 28 | |

| US-44 | Stephen Decatur | by 1820 | 65 | ↓ | 29 | |

| US-45 | United States - Macedonian engagement | 1817 | 65 | ↑ | 29 | Buckled during hardening; damage noted on original gold medal in collection of Decatur House Museum. Radial crack along axis of buckle (through inscription below battle scene) formed during striking of silver presentation medals. |

| US-46 | Jesse D. Elliot | 1818 | 65 | US-56 | 30 | Buckled (during hardening?) as noted on copper restrike medals. |

| US-47 | Robert Henley | 1817 or later | 65 | US-53 | 31 | |

| US-48 | Jacob Jones | 1817 | 65 | ↓ | 32 | |

| US-49 | Wasp - Frolic engagement | 1817 | 65 | ↑ | 32 | Original broken during hardening; replacement made by Fürst ( Julian 1977, 161). |