It is with great pleasure that I introduce the papers delivered at the 1995 Coinage of the Americas Conference. This was the eleventh such annual event, first gathered in 1984, for the expressed purpose of presenting an in-depth focus on a specific topic in American numismatics. The 1995 program, "Coinage of the American Confederation Period," embraces a brief but extremely active numismatic era in American history. We are not just concerned with coins as a metallic medium of exchange, but rather we visualize numismatics as an eclectic science which draws upon history, politics, economics, art, biography, linguistics, metallurgy, physics and chemistry. Without doubt, the papers in these Proceedings reflect this broader definition of numismatics as we explore the diverse coinages current in the Confederation period.

The Confederation period was a time of change and challenge as the young, recently freed country, strove to establish its own national identity. The new nation had no currency of its own and of necessity continued to rely on the same foreign coins which had freely circulated here since the earliest colonial times. As a consequence of the economic stagnation which followed the Revolution, the country was crippled by a major post-war depression when all gold and silver virtually disappeared from commerce. In distinct contrast, the small change medium remained abundantly stocked with token coppers, especially counterfeit English halfpence which had been in circulation for years. As a reaction against these many spurious light weight coins, several states minted their own good quality, token coppers during the Confederation period with the expectation that popular rejection of the light weight, inferior issues would drive them from circulation. For this reason, the many state copper which enrich the numismatics of this period came into being.

These Proceedings are a collection of papers which describe several aspects of the profuse coinage minted in the period after the Revolution and prior to the establishment of the Federal mint ; to 1993, some 693 different die varieties of domestic coppers have been identified with the list ever expanding as new discoveries are made. 1 The immense variety and sheer numbers of Confederation coppers have stimulated much attention and research, and rightly so. Investigators have been hampered and frustrated in their efforts since there are no surviving artifacts used in the manufacture of these coins. Thus, all our information must be extrapolated from the examination of the existing coins themselves and from literary evidence published in contemporary newspaper accounts and other documents. But this lack of immediately available data should not deter us from the continued pursuit of information about this numismatic era. Many years ago, Damon G. Douglas , well known for his research into the Fugio cents, stated it very succinctly. "The copper coinages of that critical period in American history, the first decade after the Revolution, still present unexhausted fields for fruitful research." 2

Thus, there are many challenges before us for continued numismatic research but we must remain humble in the fact that we do not have all the answers about these intriguing coinages. I believe it is safe to say that there is more that we don't know than we do know. As a result, investigators must possess the wisdom to separate appealing speculation and unsubstantiated numismatic tradition from confirmed fact. In regard to Confederation coppers, except for a few notable exceptions, we know painfully little about the mints, the mintmasters, their business associates and practices, and just how the money entered circulation. I expect that new genealogical discoveries and documentary evidence will disclose important clues as to the lives and activities of some of the individuals whose roles in these Confederation coinages have remained enigmatic. There are still untapped literary sources yet to be discovered, as exemplified in these Proceedings by Eric Newman's identity of the party responsible for the Nova Constellatio tokens. Mint attributions for many of these coppers are still unsettled; in the past, many mints were assigned based solely on the basis of deductive reasoning, some of whose logic has collapsed under closer scrutiny. Newer technology such as computer image enhancement, improved photography, and high energy, non-destructive, planchet analysis may assume a leading role in deciphering some of these mysteries.

Numismatists in general are just beginning to appreciate the counterfeit English halfpence as the most prevalent copper of the period. This new awareness has unfortunately spawned a temptation to view any crude counterfeit English halfpenny as an American product based on no firmer evidence than a rough appearance. While there is literary evidence to support American "blacksmith" type counterfeits, 3 we cannot identify them as to type and it remains inaccurate to assign every barbarous counterfeit halfpence to this side of the Atlantic. Contemporary newspaper accounts 4 reveal that local entrepreneurs did cast counterfeit halfpence which, by their nature, leave no telltale evidence as to site of origin. Thus, many cast counterfeit halfpence found in this country today may well be of domestic origin, a fact we can neither prove nor disprove. Except for the proven Machin's Mills imitations, it becomes problematic to designate other struck counterfeit halfpence as American when one considers the sophisticated and complicated infrastructure required to mint coppers. The sheer magnitude of such an operation to smelt ore, to prepare, roll, and anneal planchets, to engrave dies, and to strike coins, would have been a major business venture available to but a few in pre-industrial America . But these considerations should not deter one from continued inquiry into the counterfeit English halfpence, both domestic and imported. In fact, two important papers in these Proceedings deal with these fascinating, but humble, coppers, coins whose importance is just now earning recognition as important players in early American numismatics.

Another interesting American series, generally of English origin but contemporary to the Confederation period, includes the Washington pieces. While these tokens enjoyed no official status, it was obvious that many circulated. We are pleased to have a complete catalogue of Washingtonia by George Fuld included in these Proceedings .

To this point the emphasis has been placed on the money circulating between the end of the Revolution and the advent of the Federal mint . Whereas the coins in our cabinets today are the survivors of the economy of those times, we have another body of contemporary history documented by the medals struck to commemorate significant events of the period. As Frederic H. Betts wrote in the introduction to his brother's posthumously published book, "One is to look upon a cabinet of Medals 'as a treasure, not of money, but of knowledge'... ." 5 With the sensitivity that the holistic approach to the study of numismatics includes an appreciation of all the events and factors that shaped the history of the era under study, Alan M. Stahl has provided us an inventory of the Comitia Americana medals authorized by Congress to honor the heroes of pre-Federal America .

I wish to thank all the participants in this year's Coinage of the Americas Conference for their contributions of time, effort, and knowledge. The editorial assistance I received in preparation of these Proceedings from James C. Spilman and Michael Hodder is gratefully acknowledged. Finally, we all express our gratitude to the staff of the American Numismatic Society for making this symposium possible as a medium through which we can share our interest in this fascinating and engaging period of American history with numismatists everywhere.

Philip L. Mossman , M.D.

Conference Chairman

| 1 |

Philip L. Mossman , Money of the American Colonies and Confederation , ANSNS 20 ( New York , 1993), p. 203.

|

| 2 |

CNL 5 (1963), p. 67.

|

| 3 |

Gary Trudgen , "Gilfoil's Coppers," CNL 76 (1987), pp. 997-1000; "TN-111," CNL 77 (1987), pp. 1019-21.

|

| 4 |

Mossman (above, n. 1), p. 121.

|

| 5 |

Frederic H. Betts , American Colonial History Illustrated by Contemporary Medals (

New York , 1894).

|

Coinage of the Americas Conference at the American Numismatic Society, New York

October 28, 1995

© The American Numismatic Society, 1996

The American Confederation, extending from 1781 until 1789, can be considered the period of our national adolescence. These seven years spanned the time frame between our emergence as a nation from the cocoon of infant colonialism until our start on the road to maturity as a Federal Republic. It was a "betweentimes" when our country went through all the growing pains expected from a post-pubescent, gangly teenager, such as the evolution of character and self-reliance, the development of trusting relationships with peers, and the assumption of adult responsibility. It is the monetary history of this fascinating epoch which is the focus of this year's Coinage of the Americas Conference. 1

One cannot speak of the Confederation period as an isolated historical event but rather one must consider the prior experience of colonialism which shaped our nation's adolescent personality. From 1607, with the first permanent settlement in Jamestown , until 1749, with the settlement by the English military of the garrison at Halifax , 14 British colonies were founded on the North American mainland . These colonies were very different in composition and character from one another with distinct economic, geographic and climatic diversity. In the North, the economy was dominated by forest products, fishing and small farms, whereas in the South, large plantations worked by slaves were scattered over the countryside. The population was generally concentrated in cities along the eastern seaboard. Beyond these coastal communities, occasional towns and villages of a few dozen houses punctuated the largely forested and rural landscape. Travel, communication, and commerce between the colonies, except by sea, was very difficult and tedious. Roads were poor or nonexistent; even in the best of conditions the New York to Boston stagecoach could make only 40 miles a day traveling from three in the morning to ten at night. 2 Rarely did people stray more than 20 miles from their birthplace. The population was largely of English extraction, generally illiterate, and lived on farms at a subsistence level of economy. 3 British North America was not a single country but rather a collection of "several distinct regional economies, most of them tied more closely to Great Britain than to each other... ." These "regional differences among the colonies were so sharp and ties between them so weak that it is misleading to speak of an 'American economy' or an 'American population' early in the colonial period." 4

Moreover the governments were dissimilar; only Connecticut and Rhode Island were true republics where all public officials were elected by the people. In three others— Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland —the lords proprietary selected the governors; and in the remaining nine (including Nova Scotia ), the governor was appointed by the monarch. The varied political structure of the colonies notwithstanding, England looked on these North American plantations in the same way. The natural resources and economic development of every colony were to be regulated from London and any potential profits were to be directed toward increasing the wealth and power of the mother country under a system called mercantilism. To this end, a series of restrictive laws was passed by Parliament, collectively known as the Acts of Trade and Navigation, which were designed to ensure that the colonial economies remained subservient to that of the mother country and that English interests were protected. However onerous these controls might appear at first glance, the colonies also benefited from membership in the British Empire with a large free-trading area, naval protection, easy credit, and restricted foreign competition. The negative aspects of mercantilism included suppressed colonial manufacturing, restricted foreign markets, and the export of earned specie to pay for manufactured necessities and luxuries. 6

From 1689 to 1763, the colonies became entangled in the North American extension of a series of European conflicts as continental governments continued a ceaseless drive for power. England's war machinery was fueled to a large part by raw materials from North America , consistent with its mercantilist policies. In addition, Parliament expected that the colonies would bear some of the financial burden of the so-called French and Indian Wars. 7

Until 1763, the Navigation Acts had little practical impact on the colonies since they were largely ignored or effectively circumvented by experienced smugglers. In spite of these restrictive laws on the books, the local economies expanded and prospered. But, with the peace following the final French and Indian War, the scene changed. England , in 1763, had now emerged as the most powerful nation in Europe , but with a massive war debt. To bolster its economy and recoup its strength, England now turned its attention across the Atlantic with renewed vigor and began to enforce the old Acts of Trade and Navigation in an attempt to squeeze from their plantations all their natural wealth. George III and his Tory government looked on the colonies not as political communities but simply as chartered companies and crown possessions where any freedoms or popular assembly existed only at the king's pleasure. For the first time, England stationed a permanent standing army in the colonies which was three times larger than that deployed on the battle front during wartime. It was evident that the presence of such troops was intended "to control rather than to protect." 8

Parliament passed even more unpopular laws which were designed to benefit English rather than colonial interests. As if this increased control was not bad enough, the colonial economies were crippled by an oppressive post-war depression when foreign trade and revenue from exports virtually ceased. The use of paper money in the colonies, which since 1690 had been helpful in financing local initiatives, was severely regulated in 1751 and again in 1764 by laws specifically engineered to ensure that English merchants be paid in hard currency rather than unstable paper. Parliament, still operating under the tenants of mercantilism, was always ready to manipulate the colonies for England's benefit but rarely inclined to assist their overseas dominions for their sake alone. Now sugar, tea and other imports were heavily taxed as an additional revenue measure. If it had been enforceable, the Stamp Act would have severely encumbered all local enterprises. Common law rights to trial by peers in the colonies were abrogated. Taxation without representation became the rallying cry as the Stamp Act Congress asserted that the colonists had the same native rights as all free Englishmen. The maturing colonies had outgrown their dependence on England and resented this increased control over their lives which London was now exerting in the postwar period after 1763. Unfortunately the British government "lacked the wisdom and the political genius" to recognize the liberties of its overseas citizens as defined and protected under the English Constitution and blindly perceived no need to reconfigure their imperial organization to accommodate these natural freedoms. The colonies did have some vocal support in Parliament, notably from William Pitt and Edmund Burke . Pitt's advocacy was duly acknowledged by a medallet struck in his honor. While George III interpreted the rebellious actions of the colonists as "insufferable disobedience" "requiring disciplining," Pitt , in his wisdom, recognized that if violence ever erupted, any peaceful resolution or reconciliation would be difficult. His conciliatory efforts were constantly thwarted by a king dominated Tory Parliament. Push came to shove on April 19, 1775, at the Battles of Lexington and Concord when the British attempted to seize colonial munitions. A skirmish escalated into a full fledged war just as Pitt had predicted. By the summer of 1776, there was no vestige of royal authority in any of the colonies which had become openly hostile toward all forms of centralized power. Their basic conflict was not primarily to gain political and economic independence from England but rather the colonists wished to retain those historical freedoms of free Englishmen which they had enjoyed from the beginning and now were threatened by an insensitive and autocratic monarchy and Tory Parliament. 9 While many colonial Tories remained loyal and hoped for a reconciliation, other factions pressed for complete autonomy. 10

This is an incomplete thumbnail sketch of the economic and political scene in North America at the outbreak of the Revolution, a conflict whose causes were multifactoral and cannot be explain ed by any single circumstance. All of a sudden a unique situation was at hand in North America . For the first time, 13 diverse, suspicious, self-sufficient colonies were forced into a position where they had to cooperate with one another to repel a tyranny which would have destroyed them individually. It was an easy task to burn the midnight oil and draft a Declaration of Independence which asserted their autonomy from an oppressive metropolitan regime. But after this proclamation which severed the bonds of colonialism was signed, sealed and delivered, these 13 colonies, who had had minimal prior interaction, still viewed each other with such mistrust they could come to no immediate consensus as to how they would govern themselves. It took until March 1781 for them to agree upon a form of self-rule which was set forth in the Articles of Confederation. And even after this polity was drafted, it was not ratified until just seven months before Cornwallis surrendered.

The Articles of Confederation were conceived as an instrument to bind the states in a firm league of friendship, but it did not establish a single nation. The collective states under the Articles of Confederation were unwilling to abdicate to a central government any more authority than they were willing to accept from their colonial masters. The financial, foreign policy and war powers set forth in the Articles of Confederation were jealously guarded by the states since nine votes out of thirteen were required for passage of most measures. While the individual states did retain the sole authority to levy taxes, they did agree to share with Congress the parallel authority to establish a mint and emit paper money. To finance the war effort, the states were unwilling to assert their prerogative and levy taxes, but instead pursued an alternative solution with a printing press and issued reams of unsecured paper money. Congress, without any taxing authority, had no alternative but to circulate bills of credit very early in the war to meet government expenses.

The monetary principles expressed in the Articles of Confederation reflected the paranoia which had been conditioned from years of English control over colonial fiscal policy. Throughout the colonial experience, hard money supplies fluctuated depending upon the strength of the individual colonial economies. Even at best, small denominational silver was always in demand for local trade. During periods of war, when the export of raw materials and supplies was brisk, earned specie became more plentiful as the economy prospered. These times of plenty were followed by cycles of postwar recession as the export market contracted and hard money became in short supply as trade languished. During such intervals of economic slowdown, when circulating hard money was scant, alternative solutions were devised to ensure adequate currency so that local commerce could continue. Such successful measures included the use of wampum in the 1600s, the development of regulated commodity monies, the minting of Massachusetts silver, and more commonly, the emission of paper currency by colonial governments either as unsecured bills of credit, as fiscal instruments backed by the value of land, or notes emitted against anticipated tax receipts.

During the Revolution, hard money was particularly scarce, driven out of circulation by an excess supply of depreciated, unsecured paper money. Directly following the war, there was a sudden abundance of specie from those areas occupied by foreign troops who had been paid in hard money. This surplus was short-lived since the country went on a buying-spree and soon the specie was returned to Europe to pay for many imported commodities and luxuries which had been in short supply during the war. As would be anticipated from prior experience, in 1784 a devastating postwar depression followed the Revolution with effects which were nearly as crippling to the country as those witnessed in 1929. 11 Exports faltered, credit was expensive, merchants were burdened with a glut of unsaleable imported goods, hard money was just not available, and many experienced financial ruin. Barter, as a medium of exchange, was revived in several areas; bankruptcies were commonplace. In Massachusetts , returning war veterans, unpaid for their years of military service, were now obliged to meet their tax bills in non-existent hard currency or face financial ruin with threats of foreclosure and debtors prison. An armed encounter between these disgruntled farmers in western Massachusetts and the militia ensued in the notorious Shays's Rebellion. To the north, the state of New Hampshire itself was bankrupt and in other legislatures there was agitation for cheap paper money to release citizens from the burden of personal debt. 12

Some historians have characterized the postwar Confederation with such labels as "the critical period" 13 of American history or "the period of peril" 14 since they speculated that the new nation was on the brink of anarchy and dissolution. Another commented that Shays's Rebellion frightened George Washington out of retirement into politics. 15 At any rate, the times were difficult. It did not take long to realize that this new government established under the Articles of Confederation was completely inept to lead the emerging nation and the need to mend its multiple defects soon became evident. This would have been an impossible task since a major flaw in the structure of this code required that any amendment must receive the unanimous approval of all the states. Instead, the entire document was discarded in favor of the Constitution of 1787. This new Federal government has stood the test of time, enduring now for more than 200 years. But this final union did not occur until the young nation resolved its serious problems of adolescent bickering and mutual mistrust. With these internal conflicts dispelled, the 13 colonial infants could now emerge "from many into one" and with this new spirit they launched themselves into young adulthood where united they faced the new and different challenges of the next century.

To this point, there have been some passing references to the currency which circulated during the Confederation. The following table summarizes the principal monies of the period:

| 1. Paper currency | a. Some Revolutionary War issues continued to circulate into the Confederation period. 17 |

| a. old issues | b. By 1786, nine states had issued specie money to provide a local currency. These were: Pennsylvania, Vermont, New York, New Jersey, Maryland, North Carolina, Rhode Island, South Carolina and Georgia . |

| b. new issues, state specie money | |

| 2. Foreign gold | Spanish doubloons, pistoles and fractional parts French guineas |

| Portuguese Johannes , moidores and divisions English guineas | |

| 3. Foreign silver | Spanish milled dollars and fractional parts English crowns, shillings |

| French crowns | |

| 4. English regal coppers | These had been imported in great numbers since early colonial days. |

| 5. Virginia halfpence | These 1773-dated coppers were legally authorized but did not circulate in any numbers prior to the Revolution. |

| 6. Counterfeit English coppers | These coins of English origin had comprised the greatest part of the small change medium for years. Following the Revolution, importation resumed and some were struck in New York State at Machin's Mills. |

| 7. Counterfeit Irish coppers | 1781 and 1782 dated coppers were common in the states. |

| 8. State coppers | In an attempt to rid commerce of the large number of counterfeit coppers, several states between 1785 and 1788 issued their own money under the authority of the Articles of Confederation in anticipation these good state coppers would be preferentially received and thereby drive the "vile" counterfeits out of circulation. |

| a. Connecticut | |

| b. New Jersey | |

| c. Massachusetts | |

| d. Vermont | |

| 9. Federal coppers | The 1787 Fugio cents issued under the authority of Congress. |

| 10. Tokens of English origin | The 1783 and 1785 Nova Constellatio coppers; various Washington issues. |

| 11. Miscellaneous American token coinages | These would include the Immunis Columbia pieces, and the many New York issues. |

During the Revolution, the states and Continental Congress had resorted to bills of credit to finance the war but these notes rapidly became valueless. Now in the postwar period, most legislatures witnessed an agitation to resume printing bills of credit so at least there would be some form of currency for local commerce and the alleviation of private debt. Many states, having learned their lessons from unsecured paper money during the war, resisted this temptation to solve their fiscal ills by notes unbacked by specie. Some of the more successful paper that held its value did continue to circulate.

As in the prior colonial period, dependency continued on Spanish and French gold and silver, Dutch silver and Portuguese gold. Since there had been a chronic coin shortage in England for many years, the export of specie coins, even to its own overseas plantations, had always been forbidden.

1. Exchange rates for European specie coins in Massachusetts monies of account current as of October 23, 1784 (Courtesy of Eric P. Newman Education Society) .

2. Exchange rates current in 1793 (Courtesy of Eric P. Newman Education Society) .

Nonetheless, this restriction was successfully circumvented and English gold and silver did make its way to this side of the Atlantic . The values of these diverse foreign currencies, in terms of local monies of account, were commonly published in tables to assist the public in commercial transactions. Fig. 1 , printed in 1784 and representative of such broadsides, is of particular interest since it also enumerates the value of English far things and halfpence in relation to Massachusetts copper. 18 Even into the early Federal period, after the decimal system had been officially adopted, the states still continued to calculate the value of their coins in the old colonial monies of account system denominated in pounds, shillings, and pence. Typical of such conversion tables is fig. 2 , published in 1793 by Samuel Sauer (Somer) of Germantown, Pennsylvania , which reckoned the value of common specie coins of the day in the several colonial monies of account as well as in terms of the new Federal denominations. 19 Although the 1793 table is dated after the Confederation Period, it was selected to demonstrate the concurrent use of the new Federal and old colonial notations, a practice which continued well into the next century. The cyclical shortage of hard money previously described, while definitely troublesome, did not necessarily suspend commerce since many large transactions, both local and overseas, could be satisfactorily transacted using bills of exchange. 20

3. Common foreign silver coins in use during the Confederation period.

(a) Mexico : 1766 pillar eight reales of Charles III

(b) Mexico : 1753 half real of Ferdinand VI also called a half bit, medio or picayune.

(c) Spain : 1719 cross pistareen of Philip V.

(d) England : 1695 crown of William III .

The Spanish American milled dollar, first minted in Mexico City in 1535, was the most important silver coin on this continent from the first settlements until the middle of the last century. Over its 351 year history, the eight reales piece remained the world's silver standard due to its uniformity. Its fractional pieces, including the bits, levies, and picayunes, formed the backbone of our silver small change medium. Although never recognized with legal tender status due to its lower silver content, the pistareen, a debased two reales coin from mainland Spain , was another very important player in our colonial and Confederation periods ( fig. 3 ). Spanish, Portuguese, English and French gold commonly traded as high denominational specie coins for the first 250 years of our history ( fig. 4 ). Since the early Federal Mint could not keep up with the demands of the coinage requirement for the United States , these foreign gold and silver specie coins continued as legal tender in this country until demonetized by the Act of February 21, 1857. 21

4. Common foreign gold coins in use during the Confederation period.

(a) Mexico : 1762 doubloon of Charles III.

(b) Brazil : 1767 half Johannes of four escudos of Joseph I.

(c) France : 1641 louis d'or ( French guinea ) of Louis XIII.

(d) England : 1688 guinea of James II.

During the Confederation, the copper small change medium was plentiful in direct contrast to the hard coin money which was in short supply during the devastating post-Revolutionary War depression. Whereas the circulating gold and silver money was from the countries described above, the copper money was regal English since there was no prohibition against the export of Tower halfpence and farthings. In fact, from 1695 to 1775, about 17% of the copper output from the Tower Mint was exported to the North American colonies, amounting to some £69,000. In 1749 alone, 10 tons of cop- pers, about a quarter of the year's production of farthings and halfpence, were included in a large sum of money sent to Massachusetts by Parliament as partial repayment of the debt incurred during the French and Indian Wars. The only legitimate copper of the Revolutionary period was the Virginia halfpenny minted for the colony in England . These coppers were delivered just weeks before the War broke out and so were withheld from general circulation until hostilities ceased ( fig. 5 ).

6. (a) 1737 regal halfpenny of George II (152.1 grains).

(b) This crude cast counterfeit (98.6 grains) is easily identified due to rough surfaces and the telltale cud above the kings head where the metal was poured into the mold. It is smaller due to shrinking of the molten metal upon cooling.

Since the currency value of regal English coppers was about double the intrinsic value of the metal plus the minting costs, significant profits were available not only to the king but also to the counterfeiters who surfaced in great numbers to make their fortunes. These clandestine forgers had little to fear from the authorities since the punishment, if apprehended, amounted to a virtual slap on the wrist. At first bogus coppers were sand cast but soon these illegal operations began striking counterfeits in presses from engraved dies. By 1753 in England , it was estimated that about half the circulating copper was counterfeit. The large numbers of regal English coppers, sent legally to the colonies, were quickly followed by the spurious ones. Soon commerce was flooded with these light weight, counterfeit issues which were accepted by a generally uncritical public whose only concern was that they receive full value in commerce for their token coppers. The importation of these coppers, interrupted by the Revolution, resumed again after the War and figured even more prominently during the Confederation (figs. 6 , 7 ).

7. (a) 1775 regal halfpenny of George III (154.9 grains).

(b) Struck contemporary counterfeit (121.1 grains) from engraved dies.

Since the counterfeit copper industry in England was so profitable, as evidenced by the vast numbers which circulated on both sides of the Atlantic , it was only natural for this illegal activity to spread into British North America . Original research on counterfeit George III halfpence was presented in the symposium by Charles W. Smith . Many counterfeit English halfpence of domestic manufacture have been identified, the largest source believed to have been Machin's Mills in Newburgh, New York ( fig. 8 ). Similarly, Irish halfpence and farthings were extensively counterfeited. Both the false and regal issues were exported to America in large numbers as substantiated by a 1787 report from New York . In fact, 1781 and 1782 bogus Irish halfpence were commonly used as planchets for several Vermont state issues ( fig. 9 ). The exportation of these counterfeit halfpence from Ireland and England into British North America is examined in detail by John M. Kleeberg .

9. (a) 1782 regal Irish halfpenny of George III (141.0 grains).

(b) 1782 contemporary struck Irish counterfeit halfpenny (92.1 grains). The latter were commonly used as host coins for certain Vermont coppers.

In 1786, one estimate asserted that nearly half the coppers in circulation for the previous 20 to 30 years were counterfeit. The new Articles of Confederation empowered both the state and national governments to coin money and, under this authority, Connecticut in 1785, New Jersey in 1786, and Massachusetts in 1787 commenced to mint their own copper coinages with the expressed goal of ridding commerce of the vile, base coppers, which were perceived as inflicting financial injury, especially upon the poor. The plan was to mint state authorized coppers of consistent quality with the expectation that the citizens would only accept these new, true weight coppers while rejecting the counterfeit halfpence which comprised the bulk of the money.

Although not a member of the Confederation, Vermont also adopted the same practice in 1785 and issued its own coppers. The early history of this republic and the background of its mint are the subject of a paper by Pete Smith . The attractive landscape coppers, whose reverse motif is similar to the Nova Constellatio issues, were products of the Rupert mint in 1785 and 1786. Later bust issues are thought to have been inspired or directly copied from Connecticut designs. Certain bust right issues were struck over unnegotiable 1785 Nova Constellatio coppers and counterfeit Irish halfpence.

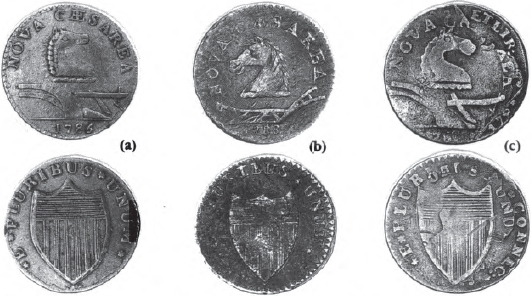

In 1786 the New Jersey Assembly strove to improve the quality of the small change medium by authorizing three million legal tender coppers of 150 grains each, for which privilege the licensees would return a 10% royalty to the state. The official contract was shared by two mints but several clandestine operations have also been identified making a total of 139 New Jersey die varieties with a total combined coinage of about four million pieces. The earlier issues from Rahway and Morristown were typically of high quality but soon there appeared lighter weight coppers which discredited the integrity of the full weight coinage ( fig. 10 ). These inferior coppers included the 1788-dated issues attributed to Morristown and others, overstruck on light weight host coins, believed to be from Elizabethtown . Recent work by Hodder has added much to our understanding of this complex series. 22

10. New Jersey coppers: (a) 1786 Maris 14–J from the Rahway Mint (147.8 grains).

(b) 1788 Maris 50–f, one of three horse head left varieties (141.7 grains).

(c) 1787 Maris 56–n, struck over a 1787 Connecticut Milller 30–hh. 1 (129.6 grains).

There are 355 die varieties of Connecticut state coppers included within 26 distinct bust types dated from 1785 to 1788 with an estimated total production of about seven million. The only authorized mint was the Company for Coining Coppers of New Haven which struck coppers from dies engraved by Abel Buell . Their franchise may have passed legally to James Jarvis and Co. on June 1, 1787, who continued to mint Connecticut coppers on stock designated for the Federal Fugio contract. Besides these two mints, at least five or six prolific clandestine operations existed which increased their profit margin by ignoring the 5% royalty payable to the state and by minting coppers considerably below the prescribed 144 grains ( fig. 11 ). The end result was that the abundant light weight counterfeit Connecticut coppers just added to the glut of inferior coppers already in circulation rather than to replace them with a proper coinage. Thus the attempt to rid commerce of light weight coppers only resulted in more inferior coins being added to the copper medium which already was far larger than the economy required. James A. Goudge presented a discussion of certain die varieties within this very popular Confederation series.

11. Connecticut coppers: (a) 1785 Miller 3. I-L from the Company for Coining Coppers (129.7 grains); typical Mailed Bust Right issue from dies engraved by Abel Buell .

(b) 1787 Miller 20–a.2 also from the Company for Coining Coppers (142.9 grains); this standard Draped Bust Left design from both the Company for Coining coppers and the Jarvis Mint is the most common Connecticut design.

(c) 1788 Miller 2–D (114.0); this Bust Right issue is typical of those attributed to Machin's Mills weighing well below authorized 144 grains.

Whereas the three previous states awarded franchises to private individuals, Massachusetts constructed a state-run mint which produced excellent coppers of consistent quality in 1787 and 1788. These coins adhered to the new Federal standard of 157 grains. The mint operated at a loss, and this expense was one reason it was closed in 1788 ( fig. 12 ).

In addition to the coppers actually minted by the several states already mentioned, many pattern issues were also struck during the Confederation by competing contractors in anticipation that a coveted franchise would be awarded to the winner. Other issues during this period include the familiar Immunis Columbia pieces and the several New York coppers. 23 Other speculative coinages were urged for which no patterns were ever struck. Some interesting proposals, which were only visions in the imaginations of their advocates, are discussed by Richard G. Doty .

Numismatists have long observed the appearance of similar letter punches within the various state series, particularly noting those with obvious flaws or breaks. It has been intriguing to speculate that such broken punches, when identified, belonged to an individual die sinker. Thus, the temptation has evolved to treat these observed defects like the signature of the engraver and the attempt made to assign a particular artist or mint of origin to many of the state issues described above. This approach has not withstood the test of time and its deficiencies are reviewed in detail by John Lorenzo in regard to James Atlee and the broken "A" letter punch.

Soon after the peace treaty, a large number of copper tokens arrived in this country from England which circulated widely. These Nova Constellatio coppers were lighter than the state issues yet to come and were frequently used as host coins on which to overstrike Vermont, Connecticut and New Jersey coppers. Eric P. Newman has newly discovered facts concerning these important coppers. Another large series of tokens dated from 1783 to 1795, primarily of English origin and collectively termed the Washington coppers, appeared immediately after the Revolution. George Fuld has prepared an extensive study of the Washingtonia minted during the Confederation period.

We have seen how the state mints failed to drive the light weight counterfeit coppers out of circulation and in most cases just contributed to the plethora of inferior coins. So, as one might expect, when the Federal government tried its hand at the same game, it also failed miserably. The Fugio coppers, the first United Stated authorized coin, were minted under a contract awarded to James Jarvis , the minter of most of the 1787 Connecticut series ( fig. 13 ). Only a small percentage of the authorized amount was ever minted and these were released in the summer of 1789 in New York at a time known as the Coppers Panic when coppers ceased to circulate, an episode in the numismatic history of the Confederation worth noting.

In 1789, the nation still remained in the clutches of a serious postwar depression. Although earned money from exports was scarce and there was a dearth of circulating specie, the small change medium was still flooded with inferior grade coppers. Merchants were overwhelmed with large quantities of this mostly counterfeit, token coinage, which were only negotiable in small sums. It had no legal tender status, it could not be exchanged for gold or silver; in short, no one wanted it. In the summer of 1789, public confidence in this token copper medium collapsed and overnight the exchange rate plummeted from 20 to 48 coppers to the New York shilling. It was an economic calamity for the poor whose entire wealth was invested in this unstable medium. Copper coins were not even valued as scrap metal because the world price for copper had fallen to an all time low. This coppers panic primarily involved the area within the economic orbit of New York and Philadelphia . New Jersey coppers were received preferentially because of their legal tender status and soon traded again at 24 to the shilling. As the world price for copper dramatically rose into the next decade, faith in copper coins returned and the once discredited issues were called back into circulation while new ones were minted by the Federal government.

In the meanwhile, the New Constitution of 1787 had been ratified since it was recognized that a more stable federal system would be necessary if this new republic were to survive as a single country rather than as a collection of 13 bickering siblings. A priority on the national agenda was to respond to the need for a standardized national currency. Included in this plan was the blueprint for a Federal Mint which opened in 1793 to provide for the monetary needs of the new republic. It took several years before the output of the new Federal Mint could satisfy the demand for money and so foreign gold and silver remained legal tender until 1857. In the interval, the state coppers and other pre-Federal coins and tokens took up the slack in the small change medium and continued to circulate in some parts of the country as late as 1856. Many worn Confederation coppers succumbed to a less noble fate and ended up as scrap metal for sleigh bells, buttons and frying pans. Other monetary changes were also slow since old habits die hard. For many years people continued to calculate in the old colonial money of account notations of £, s ., and d.

This overview of Confederation coinages has been just that; a summary of the first episode of our national numismatic heritage. Considering the economic and political complexities of the period, it becomes easy to understand the factors that gave rise to this vast copper coinage which so enriched this era and continues to stimulate interest and research today.

| 1 |

The author is grateful to Eric P. Newman for his critical review of the manuscript and for the use of

figs. 1 and 2.

|

| 2 |

John Fiske , The Critical Period of American History ( Cambridge , 1899), p. 61.

|

| 3 | |

| 4 |

John J. McCusker and Russell R. Menard , The Economy of

British North America

( Chapel Hill , 1985), p. 12.

|

| 5 |

Fiske (above, n. 2), pp. 64-65.

|

| 6 |

McCusker and Menard (above, n. 4), pp. 50, 354; Lacy

(above, n. 3), p. 37.

|

| 7 |

These conflicts, collectively called The French and Indian Wars, included King William's War (1689-97), Queen Anne's War

(1702-13),

King George's War (1744-48), and lastly the French and Indian War (1754-63).

|

| 8 |

Lacy (above, n. 3), pp. 37, 83; quote p. 83.

|

| 9 |

This was the major difference between the American Revolution and the soon-to-follow French Revolution where the common people

had a

long term history of economic and political oppression. These two revolutions were entirely different in their complex causation

and

neither is explained by any single factor. See George Rude , The French Revolution

( New York , 1988), passim.

|

| 10 |

Lacy (above, n. 3), pp. 69, 85, 121-27, 128, 132-33; quotes pp. 69, 128.

|

| 11 |

McCusker and Menard (above, n. 4), pp. 373-74.

|

| 12 |

This state specie money, slanderously termed "rag money" by its critics, was unsecured emergency money issued to provide

circulating

currency during this monetary crisis. See Eric P. Newman , The Early Paper Money of

America

( Iola, WI , 1990), p.18

|

| 13 |

Fiske (above, n. 2).

|

| 14 |

James Phinney Baxter , "A Period of Peril," Historical Addresses ( Portland, ME ), April 30, 1889.

|

| 15 |

Merrill Jensen , The New Nation. A History of the United

States During the Confederation, 1781-1789 ( New

York , 1950), p. 250.

|

| 16 |

This section is only an introduction to a very involved era of numismatic history. A complete treatment of this subject is

found in

Philip L. Mossman , Money of the American Colonies and Confederation , ANSNS 20

( New York , 1993).

|

| 17 |

Joseph B. Felt , Historical Account of Massachusetts

Currrency ( Boston , 1839), p. 198, states that the January 26, 1779 small change notes "are

still issued plentifully by our Commonwealth...thus far, they appear to have been sustained in their credit." See also Newman

(above, n. 12), pp. 188-89.

|

| 18 |

See Eric P. Newman , "1764 Broadside Located Covering Circulation of English and Farthings in New England " CNL 100 (1995), pp. 1531-33, for a recent

discussion of this sujbect.

|

| 19 |

Figs. 1 and 2 are courtesy of the Eric P. Newman Numismatic Education Society.

|

| 20 |

Reduced to its simplest terms, a bill of exchange is created when one party purchases from another party a portion of his

credit

balance which is held by a third party. American merchant A has a credit balance with London merchant A; American merchant

B wants to buy some English goods from London merchant B, but he has neither credit nor specie coin to send by ship. Therefore,

American merchant B purchases

from American merchant A a portion of the latter's credit balance held by Londoner A. American B remits this bill of exchange,

purchased from American A, to London merchant B to pay for his goods. American B

pays American A with local paper money of account which was probably unnegotiable in England .

|

| 21 |

See Oscar G. Schilke and Raphael E. Solomon , America's

Foreign Coins ( New York , 1964), for a definitive discussion of

this interesting topic.

|

| 22 |

Michael Hodder , "The New Jersey Reverse J, A

Biennial Die," AJN 1 (1989), pp. 195-237 and " New

Jersey Reverse 'U': A Biennial Die," The American Numismatic Association Centennial Anthology (

Colorado Springs , 1991), pp. 19-34.

|

| 23 |

Michael Hodder , "The 1787 ' New York ' Immunis Columbia ; A Mystery Re-Ravelled," CNL 84 (1990), pp. 1203-35.

|

Coinage of the Americas Conference at the American Numismatic Society, New York

October 28, 1995

© The American Numismatic Society, 1996

Even the most casual collector is fascinated by a counterfeit coin. Perhaps part of this fascination is based upon the fact that a counterfeit coin has a story to tell that goes far beyond government production quotes and conversion of moneys of account. It has a personal component to its history and seems to struggle to speak out with an individual voice. I have often heard colleagues remark, when inspecting a George III counterfeit halfpenny, "If only this coin could talk!" In my opinion, to a certain extent, coins can tell us much about themselves if we ask the right questions and listen carefully and critically. 1

The purpose of this study is to look at the contemporary counterfeit George III halfpenny from a scientific and statistical point of view. There exists a growing and exciting literature on both the taxonomy (classification by style and die type) and socio-economic basis for the production of these counterfeit coins. 2 Catalytic to these recent studies is the continuous flow of excellent scholarship documented by the Proceedings volumes of the Coinage of the Americas Conference, sponsored annually by the Ameican Numismatic Society, ANS Museum Notes (now American Journal of Numismatics) and the Colonial Newsletter.

I became interested in the British George III contemporary counterfeit halfpenny series about ten years ago, but it was only in 1992/93, when on sabbatical at the University of Oxford , that I began to look at this series from a new perspective. In the summer of 1992, I was offered a number of counterfeit examples by a local coin dealer in Oxford . I mentioned to him that this coin series not only circulated in his country, but it also circulated during the colonial and confederation periods in my country. An interesting conversation followed in which he informed me that the most common date in the counterfeit series was 1775, but that was not the case for the regal series they were imitating. He was also of the opinion that the counterfeits were substantially lighter in weight, on average, than the halfpence produced by the Royal Mint . A cursory examination of my handful of coppers supported his observations.

Compelled by scientific curiosity to get a more quantitative picture of the series, I approached a colleague in the Department of Materials, where I was studying, to sponsor me for a library card (reader's ticket) for the numismatic library in the Ashmolean Museum , which he kindly did. For many weeks thereafter, I spent my spare time systematically going through the numismatic literature trying to answer the simple question, "Of the six years 1770, 1771, 1772, 1773, 1774, and 1775, what is the relative frequency of occurrence of the counterfeit halfpence?" There were some tantalizing hints but apparently no one had carried out a careful date analysis study per se. I found detailed information about the production of the series by the Royal Mint , but mostly anecdotal information about the counterfeits. By mid-winter, my spare-time interest had grown into a project. It had also expanded in scope to include a plan to assemble a collection of counterfeit examples while in England , and a comparative assembly collected back in the U.S. from sources not directly traceable to English sources. In addition, I soon came to realize there were examples with dates outside the regal interval (1770-75), interesting questions on weight and size, and virtually no information on elemental composition as it applies to mining and smelting sources. These topics address issues of production and distribution. Guided by the old scientific adage, to measure is to know, I set out to try to find answers to this ever-growing list of questions. The results of some of my studies are incorporated in this paper.

Collecting, analyzing, and presenting data, in a broad sense, is what is meant by statistics. It is a very practical way to understand a large population, by looking at a smaller sub-group of the population, called a sample. For instance, by shaking out a few piles of M & Ms from a bag, we can pretty much assure ourselves (infer from the sample) that the number of red M & Ms in the bag is the same as the number of green M & Ms in the bag, even though we have not examined the entire contents of the bag (the population). However, for the sample to be a fair representation of its population, care must be exercised in how the sample is taken. (We wouldn't want to hire a color-blind M & M statistician!) We also need to know whether the population we are sampling is biased. (Did someone get to the bag before it was sampled and eat some of the green M & Ms?) These are major issues in any statistical study and since we know that a coin collection can be a highly biased group of examples, not at all characteristic of the general population from which it was assembled, the challenges of using a fair sampling technique and assuring that the population is unbiased, are formidable.

Collections, by their very nature, are assembled with specific goals in mind. I have a friend who collects shillings. It makes a beautiful collection but it is certainly not representative of the general population of British coinage, or even the population of British monarchs. He also specializes in coins of Charles I and thus his shilling collection incorporates this interest (is biased in this regard) and therefore does not evenly represent the population of all British shillings.

To minimize both sampling error and population bias in this study, I have taken the following measures. First, I assembled a collection of 300 counterfeit examples under controlled situations, sampled as fairly as I could—without regard to grade, date, or cost. I would look at the George III counterfeits available at coin shops or market stalls throughout England and I would either buy all that were offered or buy none. The point being, I did not pick and choose by grade, date, or any other criteria. In addition I regularly purchased examples from two coin dealers who acquired large lots for me using this all or none technique. The only criterion for rejecting examples was based upon damage, excessive corrosion or coins with unreadable dates. Since I was interested in date analysis as well as weight and size, damaged coins (holed, bent, or deeply pitted) were of no use. It took two years to assemble The Study Collection used for this project. At the same time, and in a similar way, I put together a smaller collection of regal examples.

I have also inventoried a medium size private English collection and a large private U.S. collection, each assembled, to my satisfaction, in an unbiased manner. 3

Upon returning to the U.S., I assembled an inventory of examples of George III contemporary counterfeit halfpence with no known direct English sources. This was very difficult and after considering nearly 300 coins, I have chosen to include 60 examples in this inventory. These include coins from the archaeological record (sites prior to 1857 in northern New England ), coins through bequest to historical societies (small groups with no systematic effort to "round out" the holding), and purchased coins for which I was able to trace at least three owners in the U.S. previous to me having no known mail order component to their collecting hobby, and no military service in Europe .

A statistical study of these collections, as well as others, and a discussion of the elemental metallic composition of both counterfeit and regal examples will be presented in the sections that follow.

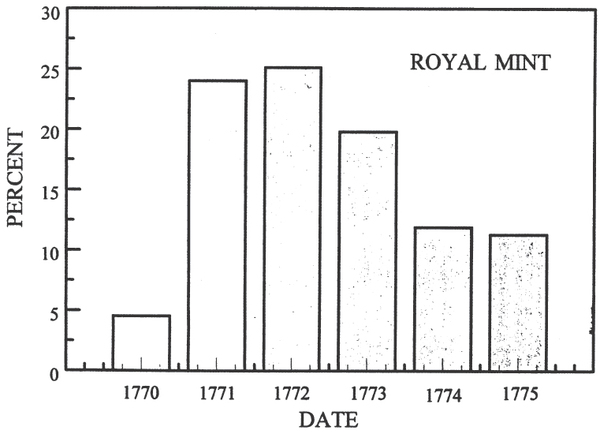

We begin this section with a look at the regal production of George III halfpence. In response to both a lack of sufficient silver coinage in circulation and "after London Tradesmen had petitioned for a supply of new copper coin, in order to throw counterfeits out of circulation," 4 the Royal Mint resumed minting of copper in 1770. This "Experiment of a Temporary Relief to the Public" 5 continued for six years. The output of halfpence from the Royal Mint during this period, in long tons, was: 1770, 9.0; 1771, 55.0; 1772, 50.5; 1773, 39.7; 1774, 24.0; and 1775, 22.8 for a total of 200.95 long tons. In terms of percentage of total production, the values are: 1770, 4.5%; 1771, 24.0%; 1772, 25.1%; 1773, 19.8%; 1774, 11.9% and 1775, 11.3%. These values are illustrated as a histogram in fig. 1 . We see from these numbers that the regal production of George III halfpence was concentrated in the years 1771, 1772, and 1773, with over 70% of the output during that period.

We turn now to the date distribution of counterfeit George III halfpence with the same date range as the regal issue, namely 1770-75. However, one must keep in mind that the date on a counterfeit coin represents only the earliest hypothetical date of circulation and not necessarily its actual earliest date of circulation or its date of production. We will return to this point at the end of this section.

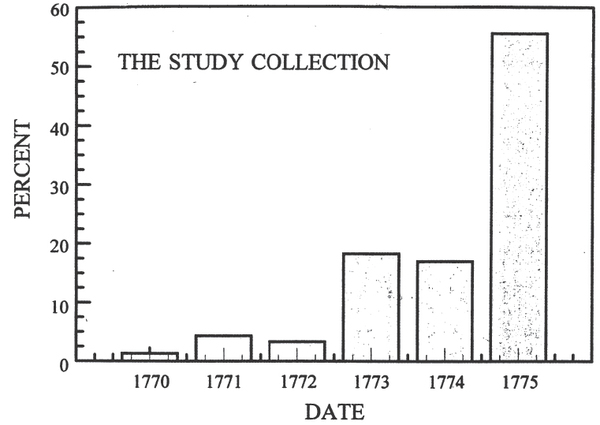

We first consider The Study Collection identified above. This is a medium size collection of 300 coins assembled in such a way as to represent, as closely as practical, the extant population in England today. The distribution by date for The Study Collection is 1770, 4; 1771, 13; 1772, 10; 1773, 55; 1774, 51; 1775, 167 or by percent 1770, 1.3%; 1771, 4.3%; 1772, 3.3%; 1773, 18.3%; 1774, 17.0%; and 1775, 55.7%. These values are illustrated as a histogram in fig. 2 and stand in dramatic contrast to the regal production values in fig. 1, in at least two significant ways. The most obvious difference is that over 50% of the counterfeit pieces are dated 1775. Secondly, nearly 90% of the counterfeit pieces are concentrated in the last three dates. One, of course, might say that we should not expect the production of counterfeit examples to correlate in any way with the production of regal examples. However, this is not what the merchants of London had expected when they petitioned the Royal Mint for a new coinage. They expected precisely the opposite effect, namely, that the new coinage would drive the counterfeit coinage from circulation! This was definitely not what happened.

Contemporary accounts of the profound extent of counterfeit production are numerous. Matthew Boulton of Soho,

in a letter to Lord Hawkesbury dated April 14, 1789, states: In the course of my journeys I observe that I

received upon an average two-thirds counterfeit halfpence for change at toll-gates, etc. and I believe the evil is carried

into

circulation by the lowest class of manufacturers who pay with it the principal part of the wages of the poor people they employ.

They purchase from subterraneous coiners 36 shillings worth of copper (coins in nominal value) for 20 shillings, so that the

profit

derived from the cheating is very large.

Fig. 1. A Date Distribution Histogram of Royal Mint Production of the English George III Halfpenny Series

Fig. 2. A Date Distribution Histogram of English George III Contemporary Counterfeit Halfpence in The Study Collection

In a letter to King George III , ca. 1800, the Earl of Liverpool writes: It is

certain that the quantity of counterfeit copper coins greatly exceeds the quantity of legal copper coins: the Officers of

the Mint were of the opinion, in the year 1787, that even then they exceeded the legal copper coins. Their

number has certainly increased ever since: the quality of these counterfeit copper coins is in truth beyond calculation.

To estimate the amount of counterfeit coinage in circulation, the Royal Mint examined a sample in 1787 and found that only 8% had a tolerable resemblance to the kings coin, the remainder being characterized from blantantly inferior to trash. 6

Before discussing the implication of the date distribution of counterfeit examples dated 1770-75 within their contemporary historic context, Table 1 sets forth below the results of four additional date distribution studies.

| Date | The Study Collection 300 Coins | Large U.S. Private Collection 1443 Coins | Med. Priv. English Collection 256 Coins | Bramah Survey 145 Coins | Yale Coll. Ca. 1886 60 Var. | Defaced London Hoard 129 Coins |

| 1770 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 2.3 |

| 1771 | 4.3 | 5.2 | 4.7 | 7.6 | 6.7 | 2.3 |

| 1772 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 4.3 | 5.5 | 5.0 | 3.1 |

| 1773 | 18.3 | 17.6 | 21.0 | 20.7 | 15.0 | 16.3 |

| 1774 | 17.0 | 17.0 | 18.8 | 14.5 | 15.0 | 14.7 |

| 1775 | 55.7 | 55.1 | 50.0 | 51.0 | 58.3 | 61.2 |

The Study Collection requires no further description at this point. The large U.S. Private Collection (third column) was put together over a 15-year period using English coin dealers as the source of examples. This collection was essentially set aside as it was accumulated and only recently (July 1995) a systematic statistical analysis by date and weight was carried out. The date distribution of this collection stands in remarkable agreement with that of The Study Collection.

The medium size English collection was inventoried in 1993 and was put together by a private collector over a period of about 10 years. As can be seen, the date distribution of this collection is in good agreement with respect to the previous two collections.

The Bramah Survey of 1929 is the name I give a "grab sample" of George III halfpence described by Ernest Bramah . 7 To get an estimate of the ratio of regal coins to counterfeit coins and a distribution by date, Bramah states, without elaboration, "For sake of comparison an analysis is here given of an assortment of the issue, got together promiscuously." Whatever "got together promiscuously" means, I consider it a "grab sample" from the extant population in 1929 and include it in Table 1, feeling its historic uniqueness outweighs its slightly less than scientific sampling methodology. The full details of The Bramah Survey are included as Appendix A. This survey, given its sample size, is in good agreement with The Study Collection.

The Yale Collection was inventoried by C. Wyllys Betts , and included as part of an address to the American Numismatic and Archaeological Society in April 1886, entitled "Counterfeit Half Pence Current in the American Colonies and their Issue from Mints of Connecticut and Vermont ." 8 Three points must be made clear to understand its inclusion in Table 1. First, the number of coins in the collection is not specified by Betts, only the number of die varieties. Secondly, Betts, in discussing the Yale Collection states, "The Yale Collection, which is the chief source of information on this subject (i.e., ca. 1886), contains counterfeits of the following dates...." Betts then enumerates the collection by date but does not state that they are all British counterfeits. Third, we are not informed how the Yale Collection was put together, that is, the sampling methodology employed. However, we see a remarkable agreement between the date distribution for the Yale Collection and The Study Collection, especially when the size of the Yale Collection is taken into consideration. Thus I have included it in Table 1 for its unique and important historic perspective.

The rightmost column in Table 1 is an inventory of the Defaced London Halfpenny Hoard. Enumeration of the entire hoard, found in an archaeological site in London in 1981, is described in Appendix B. The 129 dated George III counterfeit examples are included in Table 1. As can be seen, Table 1 establishes the relative frequency, by date, for the British George III contemporary halfpenny series.

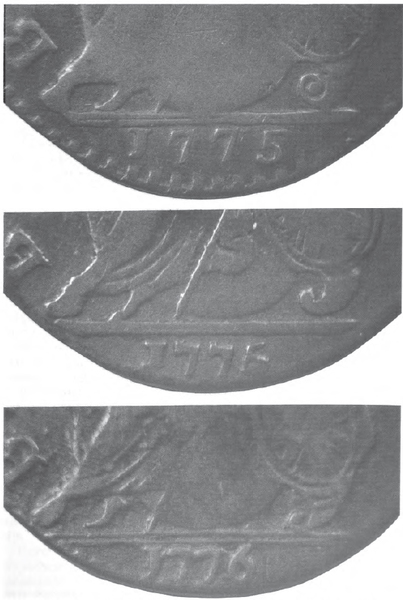

The Study Collection, as well as all the other collections, shows 50% or more of the examples are dated 1775: a remarkable result that invites interpretation. If we assume that the collections are fair samples of the population of coins produced, we are led at once to at least two hypotheses: 1) either counterfeit coin production nearly tripled from 1774 to 1775 and then abruptly stopped; or, 2) counterfeit coin production did not change substantially in 1775, but continued for several years employing the date 1775. Several indications support the second hypothesis. If we imagine, for the moment, we are in charge of a mint making counterfeit coins toward the end of 1775 or early in 1776 and our last reverse die finally fails, in order to continue production we must have new dies cut. However, we do not know if the Royal Mint plans to produce coins dated 1776. (It is not even clear if the Royal Mint knew in 1775 if it would produce copper coins dated 1776.) We can order our new dies dated 1775, we can request a die design that hedges the issue by using a 5 that looks like a 6, or we can speculate and order dies with the new year, 1776. In fact, it appears all three options were exercised.

Counterfeit halfpence dated 1776 are only about one-half as scarce as those dated 1770 (discussed below). Far more common are examples with a 5 that looks like a 6, as illustrated in fig. 3 . Here the top bar of the 5 is tilted up and the base of the 5 curls around until it almost, but not quite, forms a closed loop. This leads one to ask, if the production of counterfeit halfpence did continue past 1775, then when did production cease? There does not seem to be a definite answer to this question but, as can be seen from fig. 4 , dies with the date 1775 were still being used as late as 1797! Fig. 4 shows a counterfeit George III halfpenny struck over an English token ( Middlesex 363, J.Palmer/Mail Coach) 9 of 1797. These overstrikes are quite scarce (perhaps less than 12 known) but nonetheless provide a vivid example of the fact that the date on a counterfeit coin does not indicate its year of production.

With the substantial number of coins represented in the first three collections listed in Table 1 (about 2,000 examples), one can form a reasonable impression of the types and relative frequency of coin production errors. Of the 205 error coins examined, the most frequent error, 39%, is the double strike. This type of error occurs, as the name implies, when a struck coin is not fully ejected from the press and the dies are brought together again, making a second impression on the coin. Brockages account for 29% of the error examples. A brockage occurs when a struck coin is not ejected from the press, but a blank is fed in and struck between one of the dies and the previously struck coin.

Fig. 3. Date Styles of George III Contemporary Counterfeit Halfpence Illustrating the Transition from 1775 To 1776

Fig. 4. A George III Contemporary Counterfeit Halfpenny, Dated 1775, Overstruck on a 1797 J.Palmer Mail Coach Token, type Middlesex 363

Reverse brockages are nearly twice as frequent as obverse brockages, 63% compared to 37%, respectively. This may indicate that it was common practice to load the coin press with the reverse die on the bottom and the obverse die on top. Thus, when a coin is struck but not ejected, because it sticks unseen to the upper die, it presents its reverse to the next blank fed in, with the reverse die facing the other side of the blank from below. Remarkably, 90% of all brockages examined were full brockages, meaning the blank is fully registered over the lower die. This might indicate that some type of blank centering fixture was employed in the press feed technology and as long as the initial coin remains stuck to the die, a full brockage results. This is further borne out by the fact that off-center strikes are unusual, accounting for only 6% of all production errors. In counting off-center strikes, I did not include examples less that 5% off-center, assuming that amount of misalignment was probably within contemporary production standards. Incomplete blanks or clipped examples account for about 10% of all production errors. This results if the operator of the blank cutter fails to advance the copper sheet more than a full blank diameter or unknowingly reaches the end or the edge of the sheet. A menagerie of multiple errors, uniface examples, tab or edge pinches, and a few triple strikes make up the remainder of the error types. I was quite surprised to find five press loading errors: four examples of coins with an obverse on both sides from two different dies (not a brockage, but two fully struck obverse impressions) and one double reverse example, with each die dated 1771.

The above analysis, expressed as percentages, is based upon a population of 205 error examples. However, it would be inaccurate to conclude that because I examined about 2,000 coins, one coin in ten is a production error. Collectors tend to hold on to novel examples and even actively seek them out. Since I had control of the sampling methodology for The Study Collection, it is only from that source that I can venture an estimate of absolute error frequency. Of the 300 coins in The Study Collection, eleven are error examples: four double strikes, three off-centers, two brockages, and two incomplete blanks for an absolute frequency estimation of about 4%.

Using the dated examples of error coins, one can test the hypothesis that the generation of an error coin is an accidental happenstance. Another way of saying this is if the hypotheses is true that the generation of an error coin is a random event, then the percentage of error coins, by date, should track with the percentage of all coins by date. Using the dated double strikes, off-centers, and brockages, this hypothesis does appear to be true: 1770, 0%; 1771, 10%; 1772, 2%; 1773, 15%; 1774, 18%; and 1775, 55%; from a sample size of 152 dated errors. (Of the 205 error coins 152 were dated; all obverse brockages, and several off-centers and double strikes were without date impressions.) The match to the percentages in Table 1 for the population as a whole is not perfect, but for the small sample size it is still very good. The year 1771 stands out as errorful. This might be a consequence of the fact that, although counterfeiting of George III halfpenny series began in 1770, large scale counterfeit operations lagged by about a year, based on the number of die varieties and extant examples from 1771 as compared to 1770. Thus technical problems associated with enhanced production first showed up in 1771.

It should be noted that I have not included die cutting errors, such as misspelled legends, reversed letters, etc. in the above error analysis. Unlike a double strike or an off-center, each of which is unique, a miscut die produces innumerable identical examples. This type of error must be analyzed using entirely different statistical techniques than those employed in this project. A study of this type is planned.

The average weight of the coins in The Study Collection are listed by date in Table 2.

| Date | Average Weight (Grains) | Standard Deviation |

| 1770 | 127.95 | 7.79 |

| 1771 | 111.65 | 14.69 |

| 1772 | 121.33 | 9.96 |

| 1773 | 119.63 | 12.89 |

| 1774 | 121.60 | 14.70 |

| 1775 | 104.70 | 13.18 |

| 1770-75 | 151.20 | 4.83 |

One can see that as the practice of counterfeiting continued, lighter examples were accepted by merchants and tolerated by consumers. The trend to lighter coppers continued beyond the George III halfpenny series into the remaining decades of the eighteenth century with the proliferation of all types of commercial tokens as well as the evasive halfpenny series, the latter being of even lighter weight on average than the 1775 counterfeits. 10

At first glance it might seem to be a simple matter of careful measurement to determine whether a smaller than average blank or thinner than average sheet stock was employed in making a light weight coin. However, the thickness of a coin, considering the various aspects of the design, is not a well defined concept and the diameter of the blank is not the same as the diameter of the coin produced from it. In fact, coins struck without a collar, as the George III, 1770-75 halfpenny series was, are not round.

Metal movement during striking depends upon the coin design, among other factors. The metal in the field areas of the design, where the dies come closest together, is pushed radially outward more than in areas of high relief, like the device area. On a weakly struck coin, one can often see this effect in that the roller marks from the sheet mill on the undisturbed surface of the blank at the bust area show a rough, pocked texture, even though the field areas are smoothly struck. Thus, unless the coin design is concentric on both obverse and reverse, coins struck without a collar are not round. The Fugio series, having essentially concentric designs on both obverse and reverse, tend to be round although struck without a collar. Coins of the George III, 1770-75 halfpenny series are wider than they are high. That is, when held with the date horizontal, the horizontal diameter of the coin is larger than its vertical diameter by as much as several percent. This is because the field areas on both obverse and reverse are oriented left/right and the metal pushes out more in the horizontal direction than it does in the vertical direction. The extent to which this noncircularity takes place depends upon the operating pressure of the coin press and the softness of the blank, but the direction is determined by the coin's design. The softness of copper can be controlled during coin production. Mechanical working of copper, called work hardening, for example while drawing an ingot into a bar or rolling a bar into a sheet, makes it harder. Heating the copper, called annealing, resoftens it. A bar of copper might be annealed several times during processing to make the sheet from which the blanks are punched. Since punching is easier to carry out with hardened copper, the sheet is not annealed during the final stage of rolling just prior to blanking. The blanks are annealed before striking to soften the copper in order to help assure a well-defined image.

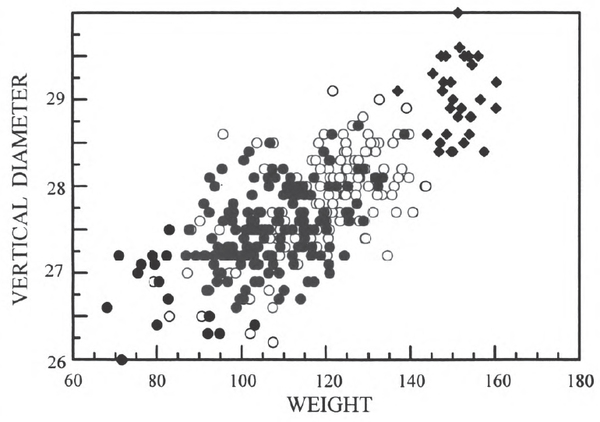

Fig. 5. A Correlation Plot of Weight, in Grains, versus Vertical Diameter, in Millimeters, for The Study Collection. Examples dated 1775 are shown as solid circles and 1770-74 as open circles. Regal examples, 1770-75, are shown as solid diamonds

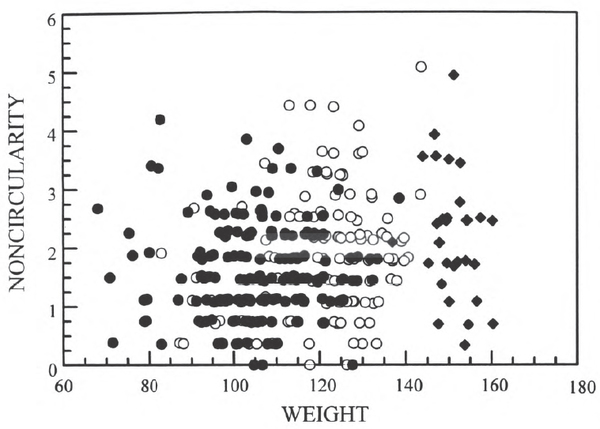

Fig. 6. A Correlation Plot of Weight, in Grains, versus Noncircularity, in Percent for The Study Collection. Examples dated 1775 are shown as solid circles and 1770-74 as open circles. Regal examples, 1770-75, are shown as solid diamonds

If short cuts are taken, like infrequent annealing, cracks, delaminations, and shallow strikes result and inferior coins are produced.

We now consider the hypothesis that counterfeiters used inferior production equipment and naive technologies as compared to the equipment and technologies used by the Royal Mint . These technologies might include, but are not limited to, inferior coin presses resulting in reduced and irreproducible striking pressure and improper annealing procedures during rolling, blanking, and before striking. To test this hypothesis let us consider two pairs of correlation plots.

Fig. 5 shows a correlation plot of the weight of each coin in The Study Collection against its corresponding vertical diameter, i.e., its size. We see, not surprisingly, a strong correlation between weight and size. The interesting feature in this figure is that the solid circles are examples dated 1775, while the open circles are examples dated 1770-74. Note that the lighter 1775 coins are smaller. If coiners were unable to control the rolling process, producing copper sheet of varying thickness from edge to edge or from sheet to sheet, we might expect far more scatter of the data and little correlation between size and weight, even when smaller diameter blank cutters were employed. The solid diamonds in this figure show the correlation of weight versus vertical diameter for a small collection of regal examples. Even though the weight range of the regal examples is narrower than that of the counterfeits, the scatter in the size is essentially the same. This scatter is a measure of the variability of the production process and this figure implies, among other things, that the technical level of the counterfeiters in controlling their rolling technologies was comparable to that of the Royal Mint's ability to control its rolling technologies. I assumed in this analysis that the production of blank cutter tools, being a straightforward lathe operation, was completely controlled as far as choosing the diameter of the cutter is concerned.

Fig. 6 shows a correlation plot of the weight of each coin against its corresponding noncircularity. Noncircularity is defined as the ratio of the difference between the horizontal diameter and the vertical diameter, to the vertical diameter, expressed as a percent. Again, the 1775 examples are shown as solid circles and the 1770-74 examples are shown as open circles. Weight and noncircularity are not as correlated as weight and size. Here the scatter is a measure of the variability of press pressure and adherence to the practice of annealing the blanks prior to striking. The solid diamonds in this figure show the correlation of weight versus noncircularity for regal examples. We see a narrower weight range for the regal examples but essentially the same scatter in noncircularity. This implies that the ability of the counterfeiters to control their press and annealing technologies was similar to the Royal Mint's control of their press and annealing technologies. Thus the hypothesis that the counterfeiters used inferior production equipment and naive technologies is apparently not supported by extant coin samples. It also suggests that the lighter coins were intentionally manufactured lighter as production of counterfeit coins continued through the latter part of the eighteenth century in what appears to be well-controlled and systematic use of production technologies.

Because the various counterfeiting operations were not necessarily coordinated, there was no attempt to work within a specified range of size or weight, beyond what would be accepted into circulation. The Royal Mint did a much better job in this regard, adhering well to a prespecified weight range, 140.9-167.9 grain; average 153.4 grain and size range, nominally 28.5 mm-30.0 mm; average 29.1 mm. In all other respects the counterfeiters appear to have been technically as skilled and perhaps as well equipped as the Royal Mint . To quote C. Wilson Peck , discussing facsimile George III counterfeit halfpence, "...it is a fatal mistake to judge a specimen solely on its general appearance, as the workmanship and weight of some of the counterfeits are almost as good as the genuine ones and it is only by comparing the details (of the designs) that the spurious piece is discovered." 11