Coinage of the Americas Conference at The American Numismatic Society, New York

November 11, 2006

© 2009 The American Numismatic Society

Of all the early currency of British North America, I know of none more shrouded in obscurity than the St. Patrick series. I am not much further along in unraveling the mysteries of this fascinating Irish coinage with its New Jersey connection than I was when I began 25 years ago. To help direct my thinking, I have developed a brief topical outline of the multiple unknowns about this series that have perplexed me. I only address one of them in this paper—namely their intended denominations when first minted—a subject I have pondered for years because of my interest in the circulation patterns of early coinages.

For over 300 years, students of the coinage have been searching for any concrete facts that would establish an official, semi-official, commercial, or ecclesiastical context for the St. Patrick series. Although the large St. Patrick copper "incorporates the arms of Dublin as part of the design... it may therefore be a token issue, but whether authorised or not must remain an open question in the absence of documentary evidence."1 If the coins were officially or regally sponsored, one would anticipate some enduring paper trail or oral history. Whenever token coinages were private or semi-official substitutes for money, they were generally promissory in nature or clearly identified as merchant tokens with some provision for conversion into specie by their issuer. To further obfuscate their original purpose, the inscriptions on the St. Patrick money provide no guarantee for redemption, indication of sponsor, or mark of value. In the absence of any documentation regarding the intended denominations of the St. Patrick series, one must take a tangential approach and examine the coins themselves for what they can teach us; in other words, heed the advice of Hamlet’s Lord Chamberlain and "By indirections find directions out."

To start a very important factor must be kept in mind: all base copper coinages of that century were minted at a profit to someone, be it the king, a merchant, or a royal patent holder. As a first step in determining their proposed denominations, it is important to recall that in that era, the market value of official copper coinages equaled the combined cost of the metal, all mint charges, plus a substantial profit for the Crown and/ or patent holder. They were never emitted as an altruistic gesture for the benefit of the public, except perhaps for those few instances during an acute small change shortage, such as siege money, or where tokens issued as promissory notes declared they were redeemable in specie.

| 1 |

To mint coins and place them in circulation involves a significant capital outlay that can include the following: [1] the expense of metal planchets; [2] the fixed production costs—die preparation, minting, fees, etc.; [3] storage, transportation, emission, and distribution costs; [4] profit to the issuers; [5] other fees, payments and bribes; and [6] the added expense of currency exchange rates between England and Ireland (if made in England for Irish use). Considering the above disbursements, one can predict the minimum market rate at which the St. Patrick series was originally intended to pass, a value that may never be less than the sum of the itemized list above since the coinage would never be generated at a financial loss. The word "originally" makes an important distinction since the intended market value of the coinage, when first emitted, may have changed over time as a result of economic factors. One must bear in mind that since these were tokens, their size (diameter) and weight relationships do not necessarily determine value in the marketplace.2 While the maximum fixed production costs for the St. Patrick series can be estimated from the contemporary records of the Tower Mint for similar coinages, we cannot know with certainty the many hidden expenses, such as transportation, profit commissions/bribes, and the cost of entering the tokens into circulation. In summary, the minimum intended denominations for the St. Patrick coinages can be expressed by the following word equation into which I shall attempt to insert the appropriate numbers:

minimum intended denomination ≥ planchet cost + fixed mint costs + distribution + profit + hidden fees and exchange

The initial step in calculating production costs is to find the cost of the planchet stock, which is determined by multiplying the prevailing market price of refined copper by the average mint weight of the struck coppers:

planchet cost = weight of planchet x cost of metal

The first requirement in solving this equation is to determine the mint weight of coins fresh from the presses, which, in the absence of both records and sufficient uncirculated examples, can be a rather complex exercise. There was variation in the weight of newly struck coppers from the Tower Mint in that era; we find for example that George III halfpence had a 6.4% disparity as made or ± 4.83 grains.3 English coppers were authorized to be minted at a specific number of coins per pound and were not weighed as individual planchets. Hence, there can be a great variation between the measured weights of individual regal coins; this disparity in weight is especially evident in copper tokens and other unofficial emissions for which there were no published standards. On the other hand, silver and gold blanks were individually weighed and, if necessary, were manually adjusted prior to striking. With specie coins, any overweight members entering circulation would be immediately culled out for the melting pot and converted into bullion at a profit. Mint officials did not expend the same effort on lowly coppers whose market value included not only the expense of the metal but also the entire production cost plus a hefty profit for the issuer.

| 2 |

Robert Heslip, Ulster Museum, Belfast, Northern Ireland, personal communication, January 15, 1997.

|

| 3 |

Charles W Smith, "Weight Analysis, Weight Loss, Wear, Porosity and Grade in Copper Coinage," The Colonial Newsletter 120 (2002): 2349.

|

Returning to the above equation, we have no records of the planchet weights for uncirculated St. Patrick coppers and therefore these values must be derived by measuring existing survivors. In my previous study of the subject, I proceeded on the hypothesis that one could average higher grade coins to arrive at a close approximation of the actual mint weight of the total population of a series.4 This premise was based on a project I did comparing numismatic grade versus weight for two American copper series, Machin’s Mills imitation halfpence and Massachusetts cents. I found no appreciable difference in the average weights among the various collectable grades. Whatever variation there might have been was probably hidden by the wide range of planchet weights as indicated by the first standard deviation or error.

Table 1: Average decrease in weight in Lincoln cents with decreasing grade; mint weight 47.99 grains. 5

| ANA Grade | % Weight Loss |

| Uncirculated | 0% |

| Extremely Fine | 0.12% |

| Very Fine | 0.31% |

| Fine | 0.42% |

| Very Good | 1.07% |

| Good | 2.82% |

| About Good | 4.43% |

The study of weight loss from planchet wear, as it reflects on grade, was amplified by Charles W Smith (Table 1) in his study of Lincoln cents that recently appeared in the Colonial Newsletter.6 In this article, he presented the weights of 50 pre-1942 Lincoln cents from each of seven grades, ranging from Uncirculated to those labeled About Good. Within the collectable range of numismatic examples, Smith found that the weight loss from wear of Lincoln cents was negligible.

In the same paper, Smith interpreted a table of measurements originally compiled by Damon Douglas, who did a similar study with 130 U.S. large cents by first sorting according to technical grade and then recording the average weight of each group.7 Compared to the modern small cents, Douglas’s large cents had a greater percentage weight loss as the grades decreased with increasing wear (Table 2). This percentage loss within each grade can be used as a tool to estimate the full mint weight of uncirculated large coppers.

Table 2: Decrease in weight of 130 U.S. large cents (dated 1817 and 1851) according to wear; mint weight 168.0 grains.8 By adding the "% weight loss" factor for any grade, one can approximate original mint weight.

| Condition | % Weight Loss |

| Uncirculated | 0 |

| Extremely Fine | 0.59% |

| Very Fine | 1.19% |

| Fine | 2.38% |

| Very Good | 3.57% |

| Good | 4.76% |

| Fair | 6.55% |

| Poor | 8.93% |

Smith attributed the difference in the weight loss with diminishing condition between Lincoln cents and large cents to the fact that the much finer surface detail of small cents accounts for a small percentage of their gross weight and proportionally a smaller amount of metal is lost to abrasion. There is relatively less loss of substance for the small coins as the grade diminishes when compared to the large cents, which involve a greater quantity of metal in raised features like thick lettering and complex rims; these large and thicker elements, representing a greater percentage of the coins’ mass, must be worn away before grade is adversely influenced. Also we do not have the details of Douglas’s large cent population. The use of older production technology for large cents may have led to a greater variation in original planchet weight than that observed for small cents manufactured in a modern mint.

Encouraged by Smith’s work, which supported my hypothesis, I revisited my 1986 and 1992 data for Massachusetts and Machin’s Mills coppers and expanded the census by adding more data points from recent auctions (see Tables 3 and 4, respectively). These two coinages had been originally selected because of their positions at the opposite ends of the Confederation coppers spectrum in that Machin’s Mills had no known standards and the Massachusetts mint conformed to the Federal weight of 157.5 grains.9

Table 3: Tabulation of weight loss compared to decreasing grade for Massachusetts cents, 1787 to 1788.

| Grade | Number | Average | Median | % Loss | p Value |

| Full Weight | — | 153.6 (norm)* | 0 | — | |

| Uncirculated | 25 | 153.6±6.8 | 153.2 | 0 | — |

| About Uncirculated | 35 | 153.1±7.9 | 152.7 | 0.3% | 0.7724 |

| Extremely Fine | 42 | 152.9±7.5 | 154.6 | 0.5% | 0.7045 |

| Very Fine | 44 | 154.1±7.7 | 154.7 | -0.3% | 0.7978 |

| Fine | 13 | 149.1±5.7 | 150.3 | 2.9% | 0.0383 |

| Very Good | 6 | 146.4±9.7 | 146.0 | 4.7% | — |

| Total | 165 | 152.8±7.6 | 0.5% |

*The average for the 25 uncirculated examples at 153.6 grains was taken as the norm, although 2.48% below the authorized standard of 157.5.

The average weights of the About Uncirculated, Extremely Fine, Very Fine, and Fine groups of Massachusetts cents were examined by the Student T-test whereby each of these grades was compared to the mean weight of the 25 Uncirculated examples to determine whether any statistically significant differences existed in their average weights. A p (probability) value of 0.05 or greater indicates there is no significant difference between the two compared groups whereas a value below 0.05 is statistically significant and the calculated differences are real and cannot be explained by a mere chance occurrence. There was no statistical difference between the About Uncirculated, Extremely Fine, and Very Fine groups and their average weights can be considered uniform and viewed the same as uncirculated specimens. There should be caution in interpreting the potentially meaningful p = 0.0383 for the Fine group because the small sample size may be a cause for error.

The weight to grade ratio for Massachusetts cents was unchanged from my previous study and both sets of results are in keeping with Douglas’s large cent data. Certainly coins graded from Fine to Uncirculated would give a close approximation of mint weight, a value that could be made more accurate by adding the correction factors as prescribed by Douglas. All weight data are compared in Table 8.

The census of the Machin’s Mills coppers was expanded from the 133 coins tabulated in the 1992 tables to a new total of 227 examples with the addition of recent auction material. While there was no significant difference in weights, the new larger sample size increases precision.10 If there was any mention of porosity, microscopic granularity or roughness in its catalogue description, its weight was recorded separately. I found that 91 out of 227 specimens (40%) had some minimal planchet problems, but that the presence of these minor surface irregularities was inconsequential in influencing the average weights for the group within any grade.11 This comparison could not be not done for the Massachusetts cents, since there was no porosity noted in their descriptions.

Table 4: Tabulation of the weight loss compared to decreasing grade of Machin’s Mills imitation halfpence with 115.0 grains taken as the standard (estimated from Douglas’s data for large cents).

| Grade | No. | Average | Median | % Loss | Porous | % Porous | p Value |

| Full Weight | est. 115.0 | n/a | — | — | — | — | |

| AU, EF, | 36 | 112.2±9.7 | 111.9 | 2.4% | 5/36 | 14% | — |

| VF | 113 | 116.2±9.0 | 115.3 | -1.0% | 39/113 | 35% | — |

| Fine | 55 | 112.9±7.8 | 112.7 | 1.8% | 32/55 | 58% | 0.7016 |

| Very Good | 23 | 107.2±7.4 | 106.8 | 6.8% | 15/23 | 65% | 0.0318 |

| Total | 227 | 113.9±9.1 | 114.0 | 1.0% | 91/227 | 40% | — |

Range total sample = 88.3–146.0

It is notable that the Very Fine examples seem to have better weight retention (-1.0%) than the other higher grade specimens. A possible explanation is that although collectors view these imitation halfpence as a single series, they may have been minted in a number of locations where standards were inconsistent. Another feature is that many were struck from very shallowly engraved dies, therefore a major loss of grade may occur with relatively little loss of mass. However as a group, they seem to behave as a single entity, showing minimal weight loss until they reach a grade of Very Good.12

To summarize up to this point, a weight study of large U.S. cents, Machin’s Mills imitation halfpence, and Massachusetts cents shows that when these coinages were worn to a numismatic grade of Fine, no more than 2.9% of their mass was lost (see Table 8). Using Douglas’s analysis of large cents (Table 2), one can extrapolate a percentage value that can be added to the weight of a lesser grade coin to obtain a reliable indication of what the full mint weight is likely to have been. Smith’s Lincoln cent study for coins graded as Fine reveals only a 0.49% loss for which a reasonable explanation is offered. Since there is no recorded mint weight standard for the St. Patrick series, these studies were quoted here in order to estimate their unworn planchet mass in an attempt to arrive at a weight from which to estimate production costs.

| 4 |

Philip L. Mossman, Money of the American Colonies and Confederation (New York, 1992), 207–208; Philip L. Mossman "Money of the American Colonies and Confederation," The Colonial Newsletter 74 (1986): 132–133.

|

| 5 |

C. Smith, "Weight Analysis," 2347.

|

| 6 |

C. Smith, "Weight Analysis," 2345–2357.

|

| 7 |

Gary Trudgen, ed. The Copper Coinage of the State of New Jersey, Annotated Manuscript of Damon G. Douglas

(New York, 2003), 100.

|

| 8 |

C. Smith, "Weight Analysis," 2352–2353.

|

| 9 |

The results were essentially unchanged by averaging the additional 52 Massachusetts cents from Stack’s,

John J. Ford

, Jr. Collection. Part V, (October 12, 2004) into the 1992 data base of 113 examples.

|

| 10 |

The mean in 1992 was 111.5 ± 10.4 as compared to 113.9 ± 9.1 grains.

|

| 11 |

Within the total group, the unblemished coppers weighed 114.0 ± 8.2, while those with some indication of porosity averaged

113.3 ± 10.2 grains. Examination with the Student T test revealed a p value of 0.5374, indicating no significant difference in these values.

|

| 12 |

The p value of the Fine group shows no difference between these coins and those of the AU, EF group whereas a difference starts

to become apparent with the Very Good group, which could be removed with a larger sample.

|

Seventy-one examples of large St. Patrick coins (Fig. 1; Table 5) were examined: their technical grades compared to their respective weights as was done for the Machin’s Mills coppers and Massachusetts cents. I found that examples above the grade of Fine behaved in similar fashion to the other large coppers.13 Only four within the sample were noted as having porosity in catalogue descriptions. With the availability of 31 high-grade coppers of consistent weight, I averaged the Extremely Fine and Very Fine groups to which was added the correction of 1.1% recommended by Douglas in order to compensate for modest wear. This correction factor was proportional to the numbers of the two combined grades, suggesting a mint weight of 143.5 grains. Aquilla Smith in his 1854 paper noted that the weights of his four well-preserved large St. Patrick coppers ranged from 142 to 148 grains, averaging 144.75 grains. Similarly, Crosby’s heaviest example weighed 144 grains.14 The above historic values are consistent even considering potential sampling errors. From these measurements, I have concluded that full weight large St. Patrick coins were intended to weigh about 143.5 grains and their production costs, to be figured later, will be based on this figure. This average is more than I used in my previous work (135.7 ± 9.5 grains) of 21 specimens.15 With the increase of the number of specimens to 71, the new figure is considered more reliable.

Table 5: Weight and grade of 71 large St. Patrick coppers with average mint weight taken as 143.5 grains.

| Grade | Sample Size | Average Weight | Median | % Loss | p Value |

| EF, VF | 31 | 141.9±11.6 | 142.3 | 1.1% | — |

| Fine | 26 | 135.7±10.2 | 137.1 | 5.4% | 0.0345 |

| Very Good | 14 | 130.0 (±11.0) | 127.4 | 9.4% | 0.002616 |

| Total | 71 | 137.3±11.8 | 138.5 | 4.3% | — |

Range of total sample = 108.0–173.6

Moving on to the small St. Patrick coppers (Fig. 2), I had derived a putative mint weight of 92.3 ± 9.2 for the small St. Patrick coins in my 1986 and 1992 calculations by measuring only 46 mixed grade examples recorded from a few private collections and auction catalogues. I have now identified a significant sampling error within my prior study. With the increasing popularity of this series and more auction experience, the census of small St. Patrick coppers in the present study has been increased to 251 undamaged examples. Although I accepted minor porosity, granularity and roughness as described in their auction lot descriptions (those coins with surface irregularities are noted in the Porous column of Table 6) any specimen with significant and disfiguring porosity (although counted in the last row of the table) were excluded from any computations. The new sample included the majority of the material used for the 1986 and 1992 tabulations. Not only are there over five times more coins in the current data base, but also there are significant qualitative differences. Twenty years ago most of the recorded coins were from pristine collections where 59% were graded at Very Fine or better.17 In the current sample, just 39% fall into this category. The most significant difference within the present census of 251 coins is that 20% are Very Good while in the 1986 and 1992 studies, only 6% were in that lower grade. The reason for this major sampling error is that the older auctions of the 1980s specialized in prime numismatic material, whereas more recently there has been an increase in research oriented collections, where all grades and conditions have been examined and nothing rejected in order to do a comprehensive study of die varieties. These newer numbers more accurately reflect the entire spectrum of survivors; because of the availability of 24 high-grade examples, I selected their average as the closest representative value of the weight of freshly minted coins. Because of the slight wear as indicated by their About Uncirculated/Extremely Fine status, I added the 0.59% correction factor endorsed by Douglas to compensate for their reduction from full mint weight. The average mint weight that I now assign to small St. Patrick coppers is 95.3 grains. Aquilla Smith’s collection of 10 high quality examples ranged from 77 to 102 grains.18 Crosby’s heaviest small St. Patrick copper was 98 grains.19

I became aware of the increasing frequency of porous planchets (Porous column), especially in the lower grade examples—a feature shared by the Machin’s Mills coppers (Table 5)—while recording the updated census of 251 coppers. (It is to be recalled that my 1992 data contained a greater proportion of higher grade small St. Patrick coins, which masked this finding of porosity in worn coppers.) Within each group, if any example had microscopic or minor porosity, granularity, or roughness noted in its catalogue description, the coin was also listed in the Porous column. For example, 26 out of 51 Very Good graded coins showed some minor planchet problems. The average weight within each grade of coppers with problem-free planchets was compared to the average weight of those in the same numismatic grade of preservation with planchet irregularities (enumerated in the Porous column) to ascertain whether or not this minor porosity had any significant impact on the average weight of the entire sample. For example, the 25 Very Good coppers with normal planchets had an average weight of 82.7 ± 9.6 while the remaining 26 from the total sample of 51 weighed 81.9 ± 11.4. The p value for these results was 0.7706 indicating no difference between these two groups. The p values for the blemished versus the unblemished within the Very Fine and Fine groups were 0.3733, and 0.4165, respectively. In all cases, as with the Machin’s Mills coppers, the average values within each grade for the porous and non-porous surfaces were not significantly different.20

When the Fine through Good conditions were compared to the About Uncirculated/Extremely Fine group, it is noted from the p value of their weight differences attains extreme significance as compared to the marginal difference for the Massachusetts, Machin’s Mills, and large St. Patrick coppers in the previous tables. As these small St. Patrick coppers decrease in numismatic grade, there is an unexplained weight loss not seen in the other coppers examined.

Table 6: Weight and grade of 251 small St. Patrick coppers with full mint weight assumed at 95.3 grains.

| Grade | Sample Size | Average Weight | Median | % Loss | Porous | % Porous | p Value* |

| AU/EF | 24 | 94.7±10.6 | 91.5 | 0.6% | 3/24 | 13% | — |

| VF | 75 | 90.7±8.3 | 91.2 | 4.8% | 19/75 | 25% | 0.0942 |

| Fine | 84 | 85.9±8.3 | 85.3 | 9.9% | 30/84 | 25% | 0.00068 |

| VG | 51 | 82.3±10.5 | 81.2 | 13.6% | 26/51 | 51% | 0.000019 |

| Good | 17 | 79.4±7.7 | 81.5 | 16.7% | 14/17 | 82% | 0.000004 |

| Total | 251 | 87.0±9.9 | 86.4 | 8.7% | 92/251 | 37% | — |

| Excluded (porosity) | 36 | 77.2±9.0 | 77.1 | 19.0% | 36/36 | 100% | — |

Range of total sample = 56.7–116.8 grains

* This p value compared the weight of the various conditions with the AU/EF group. Any value below 0.05 achieves significance.

Thirty-six examples were rejected outright (not included in the 251) because of extensive porosity or some indication that they had been recovered from the ground. Others were also excluded because of an attempt by some literal "gold-digger" to pry loose the brass splasher. These brass splashers are a mystery unto themselves but have no influence on weight since the specific gravity of brass is 8.4 to 8.7, very close to that of copper (8.8 to 8.95).21 This suggests that the presence or absence of a splasher does little to alter a coin’s weight.

To summarize Table 6, the weight analysis of the small St. Patrick coppers looked like a rather straightforward exercise similar to the previous tables, but there were some unexpected findings:

The reasons for these observations, if valid, may be:

In an attempt to account for these findings, the specific gravity of a single, clean, large St. Patrick copper was measured and found to have a specific gravity of 8.90. Two small coins—one with excellent surfaces and the second with minor microporosity—were calculated at 8.89 and 8.73, respectively. These values were all within the range of copper at 8.8–8.95, but prove nothing because they could represent the average of metals in a complex bronze. In a further study of the observation that lower numismatic grade small St. Patrick tokens are proportionately lighter than other coppers of equal grade, the surfaces of two undamaged examples were cleaned with a solvent and examined with X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy to learn their composition.23 The weights of both specimens were representative of their respective Very Good and Very Fine condition grades as noted in Table 6. The first coin had the appearance of a rich brass while the second looked like leaded bronze; considering their high copper content, they, no doubt, would have passed for pure copper by seventeenth-century standards.24 The results are recorded in Table 7.

Table 7: Elemental composition of two selected Small St. Patrick Coppers examined with a scanning electron microscope.

| Coin | Grade | Weight | Comparison with Table 6 | Composition |

| #1 | VG | 74.2 grains | 82.3 ± 10.5 grains average weight of 51 examples | 97% copper; 3% zinc |

| #2 | VF | 95.5 grains | 90.7 ± 8.3 grains average weight of 75 examples | 98.4% copper; 1.4% lead; 0.2% aluminum |

As a preliminary answer to the questions raised above, there is no immediate evidence that the two planchets examined were made from an alloy, but it must be stressed that the results from two samples is neither definitive nor considered representative of the entire coinage where there may have been other planchet populations lurking. In regard to the increased weight loss, a large sample may prove this observation to have been a statistical idiosyncrasy.

Table 8: Weight loss vs. grade for the six selected coinages tabulated in Tables 1 to 6. The small St. Patrick coppers lose a higher proportion of weight with decreasing technical grade.

| Grades | Lincoln Cents | Large U.S. Cents | Mass. Cents | Machin’s Mills | Large St. Patrick | Small St. Patrick |

| Uncirculated | 0% | 0% | 0.0% | — | — | — |

| AU | — | — | 0.3% | — | — | — |

| AU, EF | — | — | — | 2.4 | — | 0.6% |

| Extremely Fine | 0.12% | 0.59% | 0.5% | — | — | — |

| EF, VF | — | — | — | — | 1.1% | — |

| Very Fine | 0.31% | 1.19% | -0.3% | -1.0% | — | 4.8% |

| Fine | 0.42% | 2.38% | 2.9% | 1.8% | 5.4% | 9.9% |

| Very Good | 1.07% | 3.57% | 4.7% | 6.8% | 9.4% | 13.6% |

| Good | 2.82% | 4.76% | — | — | — | 16.7% |

| About Good | 4.43% | — | — | — | — | — |

| Fair | — | 6.55% | — | — | — | — |

| Poor | — | 8.93% | — | — | — | — |

| Total | — | — | 0.5% | 1.0% | 4.3% | 8.7% |

| Excluded (porosity) | — | — | — | — | — | 19.0% |

In my effort to arrive at an average mint weight for freshly struck small St. Patrick coins, I discovered that as their numismatic grade decreases, there is a greater proportional weight loss than is seen with other copper coinages. Consequently, it is no longer valid to estimate the weight of freshly struck specimens by averaging a cross-section of circulated examples unless a correction factor is applied. There is the possibility that within this census there were hidden several planchet emissions of different metals, alloys or weights. Therefore, only Extremely Fine or better small St. Patrick coins can be reliably used for accurate metrological data concerning newly minted coins. We have certainly come all around "Robin Hood’s barn" to find this figure to fit into the simple formula that answers the question, "What were the denominations of the St. Patrick coinages?"

| 13 |

Summary of weights provided by Roger Moore, personal communication, November 7, 1999.

|

| 14 |

Aquilla Smith, "On the Copper Coins Commonly Called St. Patrick’s," Proceedings and Transactions of the Kilkenny and South-eastern Archæological Society 3 (1854–1855): 1–10 and Sylvester Crosby, The Early Coins of America

(Boston, 1875), 136–137, where Aquilla Smith’s paper is partially summarized.

|

| 15 |

Mossman, Money, 126.

|

| 16 |

Because of the small sample size, the accuracy of this p value is suspect.

|

| 17 |

Mossman, Money, 126.

|

| 18 |

A. Smith, "St. Patrick’s," 6.

|

| 19 |

Crosby, Early Coins: 138.

|

| 20 |

These results were subjected to the student T test to discover if the differences between the two means is significant or

due to chance. None of the differences between porous and non-porous coppers of any particular grade was significant and so

they could be considered as a single group.

|

| 21 |

The specific gravity of tin bronzes varies from 7.4 to 8.9 depending on their tin content (7.9 to 14% respectively).

|

| 22 |

In many instances, the cataloguer for both series was the same person, thus lessening the degree of observer bias.

|

| 23 |

Jeol JSM-6480LU Scanning Electron Microscope. This study was arranged and financially supported by Raymond Williams whose

participation is gratefully acknowledged.

|

| 24 |

The results were reviewed by Dr. Charles W. Smith whose helpful comments are appreciated.

|

It is instructive to digress for a moment to consider why coins lose weight. The normal decrease in grade of the small St. Patrick coppers—or any coin for that matter—may be due to genuine wear, which consists of two factors: surface abrasion of metal in which micro-fragments are sloughed into the environment and the peening effect in which the copper in the elevated design is hammered into the surface so that the dulling of identifying devices occurs without an accompanying loss of weight. The combination of wear and peening in Smith’s study accounted for a 2.82 % weight loss for Lincoln cents graded Good and 4.43% for those considered barely identifiable. Smith’s controlled study shows that the decreasing grade of circulated Lincoln cents is primarily the result of surface peening rather than the loss of abraded metal. However, there may be another more significant factor at work with low grade small St. Patrick coins, namely porosity. From both Tables 4 and 6, we have seen that minor porosity did not adversely affect weight in either the small St. Patrick or Machin’s Mills series, but the observation that significant numbers of small St. Patrick coins in lower grades have some degree of porosity leads one to think about the nature of porosity and how it might adversely affect this particular coinage in very low grades (36 examples in Table 6).

Copper is soft and relatively chemically reactive; "Thus the state of preservation of a coin can be thought of as the integrated effects of its entire physical and chemical history, from the time of its production to its current local situation."25 These irreversible changes can be induced when a copper coin is subjected to an acidic environment—such as being buried in a coniferous region, a field treated with fertilizers, or stored in a tanned leather purse, rather than residing peacefully for years in dry neutral sand. The chemical influence of an acidic milieu may produce water soluble copper salts that leach out causing macroscopic surface granularity and discoloration from complex copper oxides in a process we identify as porosity.26 Cast planchets, with their natural micro fissuring created by escaping gas during the supercooling of the metal, are more susceptible to porosity, since these minute clefts become conduits for the entrance of environmental contaminants beneath the surface of the coin with subsequent acceleration of chemical deterioration. "These voids remain available over time as host locations for weight-loss chemical activity."27 Additionally, as cast planchets cool, small gas bubbles accumulate beneath the surface causing microscopic "pock marks" and as porosity progresses, the "pock marks" extend to the surface. Perhaps the extensive porosity that appears with this series is the result of being struck on several populations of cast planchets of mixed metals that were not detected in the small sample that underwent elemental analysis.

Another situation, unrelated to casting, may also add to premature porosity. When metals are worked and subjected to stress, their internal crystalline configuration is altered making their structure harder and less malleable (so-called "work-hardening"). If such a metal is stressed again, it may crack unless, prior to reworking, it is annealed in a procedure that consists of heating the metal to a precise temperature and cooling it slowly according to a formula specific to each metal or alloy. Thus, if coins were struck from non-annealed work-hardened planchets, they would be brittle and less ductile with surfaces more prone to invasion by environmental contaminants promoting porosity. In the seventeenth century, planchets were annealed between all phases of the minting process, namely the repeated rolling of the refined metal stock into desired planchet stock thickness, planchet cutting, and planchet flattening. Adequately annealed planchet material greatly added to the longevity of the embossing dies.

One can observe the positive effects of annealing by examining the surfaces of a state copper that has been overstruck on an existing coin such as in the New Jersey Maris 56-n variety. If the host planchet were well annealed and softened, very little residual host coin detail would be evident on the parasitic 56-n, perhaps only some ghost letters around the periphery. Whereas if struck on a work-hardened, host copper that has not been annealed, there will be lighter impressions from the 56-n dies and even the central devices of host coin will remain visible. However, because the 56-n die pair was so long-lived, it is apparent that the host planchet stock was generally well annealed before receiving a New Jersey identity.

The occurrence of porosity in buried coins has been mentioned; there is at least one uncontrolled experience that speaks to this question. In 1731, some 50 immigrant families from Londonderry, Ireland, settled at Pemaquid, Maine. This fledging colony, which disbanded two years later, has been the site of intense archeological activity and revealed 17 Wood’s Hibernia coppers among the site finds.28 Charles W Smith and I had the opportunity to examine these numismatic recoveries and found that most were significantly porous, but judging from the retained surface detail, they were obviously in excellent condition when they were lost, buried, or discarded. Here is a natural experiment in which new high-grade coins were subjected only to the deteriorative effects of environmentally induced porosity. The three porous farthings averaged 46.4 grains (a 20% reduction from mint weight); the 14 halfpence without physical damage averaged 103.1 grains.29 When three well-preserved halfpence with minimal or no porosity were excluded, the average of the eleven remaining was 101.9 grains. In nature’s laboratory, where several eight-year-old coppers of known weight had been discarded and developing porosity for 270 years, the average weight loss was from 11.6% to 12.2%. Even though the numbers here are few and subject to sampling error, we are still left with another indication that the small St. Patrick tokens do not behave like other coins since even the 36 highly-porous small St. Patrick coppers lost 19.5% of their estimated mint weight. Again we must be aware of sampling errors and realize that we are describing a trend.

| 25 |

C. Smith, "Weight Analysis," 2346.

|

| 26 |

C. Smith, "Weight Analysis," 2348.

|

| 27 |

C. Smith, "Weight Analysis," 2348.

|

Having made some estimation of the average weights of the coppers as they left the mint, I now return to the question of the denomination of the St. Patrick coinages. The small planchets do not seem to show the typical degradation pattern with wear as evidenced by the large St. Patrick pieces, or any other pure copper coin. What is urgently needed is a non-destructive planchet analysis of a large sample of high-grade specimens before any surface degradation has occurred. We must be cautious because there may have been several populations of planchets: some of pure copper that behaved accordingly, and others of an alloy that was subject to a more rapid weight loss. Lacking this definite information, I have used the cost of pure copper for both coinages. These data are subject to modification as more information becomes available regarding typical planchet composition.

From his work on Lord Baltimore denaria from the Tower Mint, Louis Jordan has investigated his lordship’s potential profit from his copper coinage during the same period that interests us.30 Since Ireland did not have a copper industry at this time and relied on outside sources,31 finished planchet preparation would most likely have been done elsewhere—England in this case—and the costs presented in pounds sterling. Although Peck listed the 1672 price at 12d per pound, Challis adds an additional 4.5d for the price of finished planchets and another 2.5d for charges related to coining and distribution.32 An earlier estimate of costs by Thomas Violet places the cost of copper at 12d33—but to this, the cost of planchet manufacture and minting must be added. Considering all these variables, a reasonable estimate of the sterling cost to mint one pound of copper would be:

Copper per pound avdp. = 12d,

Planchet manufacture = 4.5d,

[Total finished planchets = 16.5d]

Cost of minting, dies, and distribution 2.5d per pound avdp. = 19d.

We may never be certain about the total production cost for St. Patrick coppers, which could have been less than 19d, because that overall fee at the Tower Mint included a number of salaries of mint officials who were not involved in token production. Furthermore, the 19d are taken as a maximum total cost, but it could have been less if there was a less expensive source for some of the small planchets. These ameliorating reductions in planchet cost could have been offset by the additional expenses incurred for transportation to Ireland and local distribution, and also by the added expenditure for the 140 or more hand-engraved die pairs which is an excessive number for such a small output. We also have no idea if the placement of the splashers required special handling at an added expense. For ease of computation, the maximum cost will be taken at 19.0d per pound of copper.

Table 9: The costs for both the large and small St. Patrick coins.*

| Large St. Patrick | Small coins as 1/4 d | Small coins as 1/2 d | |

| 1. Assumed full weight | 143.5gr. | 95.3gr. | 95.3gr. |

| 2. Coins per lb. | 48.8 | 73.5 | 73.5 |

| 3. Irish value d/lb | 24.4d | 18.4d | 36.8 d |

| 4. English mint costs/lb | 19.0d | 19.0d | 19.0d |

| 5. Costs in Irish funds** | 20.1d* | 20.1d** | 20.1d* |

| 6. Profit = Value - Cost | 4.3 d | (1.7d) | 16.7d |

| 7. Profit/Total Cost as % | 21.4% | 8.5% loss | 83.1% |

*Assuming that they were made in England but passed in Ireland. Values are given for the small coin as both a farthing and a halfpenny.

**Based on the period exchange rate of 1.00:105.56, English to Irish.

From these data, it would appear that the sponsor(s) of the large St. Patrick copper realized a 21.4% profit if it passed as a halfpenny. Assuming that the small St. Patrick coppers had the same author(s), this issue would have incurred an 8.5% loss if marketed as farthings. There would also be a significant profit if they were emitted as a lighter version of a halfpenny, but, of course, the sponsor(s) would have no control over the future business climate that could easily readjust their value downwards, since neither token carried an indication of value, the identification of the issuer, or any promise of future redemption.

In Money of the American Colonies and Confederation, I presented the evidence for why both coins were originally intended to pass as halfpence. The major premise was that they were not minted in the 1:2 weight ratio that one would expect if their sponsor(s) adhered to a farthing/halfpenny relationship. Also, because these coppers were only tokens representing real money issued for somebody’s personal gain, there was insufficient profit if the small token passed as a farthing.34 On this point, Robert Heslip of the Ulster Museum, Belfast, adds, "With a token coinage all the cost of production can give us is the minimum value at which a coin could economically circulate and size relationships do not necessarily equate to value either."35 Thus when first minted, it is the potential profit margin that determines the intended denomination, be it a farthing or a halfpenny. The distinction must be made between the denomination designated at the time of production and the subsequently adopted monetary value.36

| 28 |

I wish to thank the Maine State Museum and Dr. Edwin Churchill for the use of their data.

|

| 29 |

Eleven were dated 1723, one was 1724, and two were undecipherable; the three farthings were 1723.

|

| 30 |

Louis E. Jordan, "Lord Baltimore Coinage and Daily Exchange in Early Maryland," The

Colonial Newsletter 126 (2004): 2651–2768.

|

| 31 |

Robert Heslip, personal communication, June 27, 2006.

|

| 32 |

Christopher E. Challis, A New History of the Royal Mint (Cambridge, 1992), 366.

|

| 33 |

Challis, Royal Mint, 369.

|

| 34 |

Mossman, Money, 124–130. In 1992, using a smaller and less representative sample with a less accurate mint weight, I calculated a mere profit

of 9.8% for the small copper if it were to pass as a farthing and a profit of 49.1% for the larger piece when it passed as

a halfpenny.

|

Regarding small change, what other minor coins were the Irish people accustomed to receive and spend in the late seventeenth century? In order to study the relationship between the two St. Patrick issues and other contemporaneous Irish coinages, it is important to recall the weights of other Irish coppers of the period (see Table 10), all of which are significantly lighter. The Armstrong patent farthing is about one-quarter the weight of the small St. Patrick coin, also called a farthing by many.37 One should bear in mind that for any coin to circulate, it must be acceptable in commerce based on either its intrinsic worth or its acceptable token value as a promissory note with the prospect for redemption. Typically such tokens were minted at a considerable profit to the authors. Numismatic history is replete with examples of rejected coinages that the citizenry considered lightweight and overvalued. The unpopular copper farthings of the Harington, Lennox, Richmond and Maltravers patents are good examples.

In comparing the St. Patrick coinages (Table 9) with other coppers of the era in Table 10, it is instructive to see how much heavier they are. In estimating potential profit from each of the coinages (Table 11), many of the earlier patent coinages returned significant profits to their sponsors. This table gives us a rough idea of the minimum expected profit for patent halfpenny tokens in Ireland during that period. I suspect that since the large St. Patrick coins did not offer a great potential for profit (21.4%) the whole operation was redesigned with a small sized halfpenny intended to capture an 83.1% profit.

Figure 3. Irish billon penny of Queen Elizabeth I. Tower Mint, 1601. Department of Special Collections, University of Notre Dame.

Figure 4. Harington patent copper farthing. ANS 1940.113.462.

Figure 5. Richmond patent copper farthing. Department of Special Collections, University of Notre Dame.

Figure 7. Mic(hael) Wilson copper halfpenny token, 1672. ANS 1933.93.17.

Figure 8. Irish copper halfpenny of King Charles II (Armstrong/Legge patent), 1682. ANS 1940.113.464.

Table 10: A list of official Irish small change during the early to midseventeenth century. The St. Patrick pieces were much heavier but their legal basis is unknown.

| Sponsor | Dates | Denomination | Weight in grains |

| Elizabeth I | 1601–1602 | penny | 31.1 |

| Elizabeth I | 1601–1602 | halfpenny | 14.5 |

| Harington patent | 1613–1614 | farthing | Type 1: Range 3–7.6; Average 5 Type 2: Average 9 |

| Lennox patent | 1614–1625 | farthing | Average 9 |

| Richmond patent | 1625–1634 | farthing | Average 8.5 |

| Maltravers patent | 1634–1636 | farthing | Average 9 |

| Rose farthings | 1636–1644? | farthing | Range 9–17; Average 13 |

| Armstrong patent 38 | 1660–1661 | farthing | 20 |

| Mic(hael) Wilson | 1672 | halfpenny token | 62.739 |

| Dublin halfpenny40 | 1679 | halfpenny token | 134.6 |

| Charles II (Armstrong/Legge patent)41 | 1680–1684 | halfpenny | Authorized at 110 |

Table 11: Using 1672 mint costs, these are the relative profits from official small change Irish coppers of the seventeenth century from Table 10. Compared to similar data (Table 9, line 7), the St. Patrick coppers were not a profitable venture. All weights are given in grains.

| Period | 1601–1602 | 1613–1636 | 1660–1661 | 1680–1684 |

| Coinage | Elizabeth I halfpenny | James I and Charles I patent farthings | Armstrong patent farthing | Charles II halfpenny |

| Patent weight | 14.5 | average 9.0 | 20 | 110 |

| Coins/lb | 482.8 | 778 | 350 | 63.6 |

| Mint costs/lb | 20.1d (Irish) | 20.1d (Irish) | 20.1d (Irish) | 20.1d (Irish) |

| Irish value/lb | 241.4d (Irish) | 194.5d (Irish) | 87.5d (Irish) | 31.8d (Irish) |

| Profit | 221.3d | 174.4d | 67.4d | 11.7d |

| Profit/total cost | 1101% | 867.7% | 335.3% | 58.3% |

| 35 |

Personal communication, January 15, 1997.

|

| 36 | |

| 37 |

See John J. Horan, "Some Observations and Speculations on St. Patrick Halfpence & Farthings," The Colonial Newsletter 47 (1976): 567.

|

| 38 |

James Simon, An Essay Towards an Historical Account of Irish Coins (Dublin 1749, repr. 1810), 49–50.

|

| 39 |

M. B. Mitchiner, C. Mortimer, and A. M. Pollard, "The Chemical Compositions of English Seventeenth-Century Base Metal Coins

and Tokens," British Numismatic Journal 55 (1985), 57. The Mic Wilson tokens are brass composed of 17.8% zinc and 77.2% copper.

|

| 40 |

Simon, Essay, 53–54

|

| 41 |

Simon, Essay, 54–55.

|

Since both varieties of the St. Patrick coins are mute as to their proposed denominations, I will concentrate on the historical documentation that may assist us in learning about the rate at which they were entered into commerce (Table 12). It is unclear which of the opinions summarized in Table 12 are supported by evidence, which are just parroting previous colleagues, and which are unsubstantiated personal biases. Based undoubtedly on the ecclesiastical symbolism, early writers linked the coinage to the 1642 General Assembly of Kilkenny.42 Although this time frame is not generally supported by other considerations, an anonymous account, appearing in 1832, described the small coin as having been minted in the 1640s by the Catholic Confederation, "who in the Castle of Lea coined some of that brass money, known by the name of St. Patrick’s Halfpence, and which are of the value of a four-thirteenth of a penny sterling; but which in that period, bore a currency of one shilling." They enjoyed only a brief circulation as token shillings and then as the report infers, were reduced in value to become current as "St. Patrick’s Halfpence."43 In reference to Table 9, using a sterling value scale, such a "St. Patrick’s Halfpenny," passing at four-thirteenths of a penny, sterling (0.31d), would have cost about 0.26d to mint in 1675 funds, providing about a 20% profit. Originally provided out of necessity as shillings, not unlike the Irish gun money of a later period, there was a period when indeed this commentary confirmed that these small coins were once valued as halfpence. No mention is made of the large St. Patrick coin. Granted that this 1642 scenario may lack other historic substantiation, in terms of this current paper, the monetary considerations are logical.

Considering that more observers date these coins to the mid- to late-1670s, it has always amazed me that there were not some earlier contemporaneous comments as to their existence and appearance, let alone monetary value, particularly if some royal patronage were involved. It is certain that some of the small coppers were minted prior to 1675, since two were recovered from the yacht Mary, which sank that year in a storm.44 The only other firm piece of evidence for their early history is cited by Charles Clay in his 1869 review of Manx coinages, in which he stated that the St. Patrick coins arrived there from Ireland in about the year 1670 and were among a number of tokens tolerated on the island because of a severe shortage of small change.45 The large piece "was generally called a penny," but Clay did not comment on the value of the small coin. We have no idea how, when, or why the St. Patrick coinages arrived on the English-controlled Isle of Man, but we learn that a 1679 Act of Tynwald officially demonetized the widely counterfeited "Butchers Halfpence,"46 the "Patrick Halfpence, and copper farthings or any other of that nature." The same legislation specifically endorsed the currency of regal coppers and "the brass money called Jno. [John] Murrey’s pence." The probable motive for this repudiation of anonymous coppers was that the "Butcher" and "Patrick" tokens and plentiful forgeries were suppressing the circulation of English coinage. The 1668 Murrey piece was favorably received because it was issued by a politically well-connected local tradesman who financially secured the circulation of his tokens.

In his classic article, Aquilla Smith summarized the opinions expressed by several numismatists from the early eighteenth century.47 From the data in Table 12, based on opinions expressed between 1679 and 1869, it is evident that at least in the first quarter of the 1700s, the large and small St. Patrick’s coppers were passing as halfpence and farthings, respectively. However, those authors, writing fifty years after the St. Patrick coppers were presumed to have been minted, admitted that no clear consensus as to their origins and denominations existed, although others inferred they were both halfpence. In fact, so little was known about the St. Patrick issues, that Evelyn, the first numismatist to write about them stated in 1697, "I think" they are "Irish."48 There cannot be much less incertitude than that for an issue that may have been no more than 25 years old! Simon felt they were halfpence and farthings whereas Batty, Lindsay and "other distinguished Numismatists" considered them pennies and halfpence.49 More recently, Michael Dolley noted,

What is still not known for certain is how the two denominations were valued at the time of their first utterance. It is irrelevant

that later generations of students have assumed them to be halfpence and farthings, or perhaps pence and halfpence...What

concerns us is the value put on them at the time of their striking, and prima facie there appears to be no compelling reason they should not have been accepted as half-groats and pence.

Later, he concluded, the large pieces may have been retariffed as halfpence.50

Table 12: Denominations of the St. Patrick coins in earlier literature.51

| Date | Source and Proposed Denominations |

| 1679 | Act of Tynwald: demonetized "Patrick Halfpence, and copper farthings." |

| 1681 | Thomas Dineley illustrated the large coin as a "... halfpenny issued for the ready change of this nation [i.e. Ireland]."52 |

| 1697 | Archbishop (of York) John Sharpe: "halfpence and farthings." |

| 1715 | Thoresby presumed they were current for halfpence and farthings based on their size. |

| 1724 | Bishop Nicolson: ".are still common in Copper and Brass;" and "are current for half-pence and farthings in Ireland." |

| 1724 | Swift spoke of "the small St. Patrick’s coin which now passeth for a farthing,—and the great St. Patrick’s halfpenny" (italics mine). |

| 1726 | Leake wrote about "copper pieces, which have passed for halfpence (130–135 grains) and farthings (90–96 grains) in Ireland, but for what purpose they were coined, and by whom is uncertain...but for what value they were originally intended, or made current, is uncertain...Afterwards they passed for the value the common people put upon them; and being something heavier than King Charles the Second’s best Irish Halfpence, went currently for such."53 |

| 1745 | Harris concluded, "In this Reign (Charles II) two or three Kinds of Copper Halfpence were coined." He described the small coin and then added, "These afterwards passed for farthings, and a large Sort were coined for Halfpence" (italics mine). The implication here is that all the St. Patrick coins started as halfpence but later some passed for farthings. |

| 1749 | Simon wrote, "...the copper pieces, called St. Patrick’s Halfpence and Farthings." |

| 1832 | The anonymous "Historical Account of the Castle of Lea" dates the small St. Patrick coins to the 1640 Catholic Confederation where they originally issued as token shillings, then (after c.1650) revalued as 4/13 penny, sterling, passing as halfpence. |

| 1851 | Cane called them pence and halfpence. |

| ND | Dean Dawson and Lindsay both called them pence and halfpence |

| 1854 | Aquilla Smith, himself, while attributing the series to the period between 1660 and 1680, sidesteps the denomination issue with the disclaimer that the question "can only be decided by some better authority than has yet been discovered." |

| 1869 | Clay: On the Isle of Man in 1670 were "Patrick pence, and halfpence, or as stated by some, halfpence and farthings...the large piece ... is generally called a penny." The other coin is called "the small piece." |

| 1978 | Michael Dolley wrote that the coins could have started in 1675 as "half-groats and pennies." |

The review of these comments by earlier numismatists regarding the intended value of the two copper tokens indicates that they all make the assumption that the two different sized issues represented two separate denominations that were minted and circulated simultaneously. It appears to me that prior writers were so completely mesmerized by the putative size correlation of farthing to halfpenny that they completely overlooked the implication of the cost/profit relationship in their manufacture. The large planchet coppers probably came first and were then replaced by the small planchets to increase minting profits. Both were intended as halfpence but the small tokens were subsequently retariffed as farthings.

This is precisely what Swift wrote in 1724. In George Faulkner’s 1735 edition of The Drapier’s Letters, which included Swift’s revisions,54 we read his comparison of William Wood’s halfpence to the halfpence of earlier periods:

... Butchers Half-Pence, Black Dogs and the Like, or perhaps the Small St. Patrick’s Coyn which passeth now for a farthing55...For I have now by me some Half-Pence coyned in the Year 1680 by vertue of the Patent granted to my Lord Dartmouth, which was renewed to Knox, and they are heavier by a ninth Part than those of Woods, and in much better Metal.56 And the great St. Patrick’s Half-penny is yet large than either.

Since this remark appears during a discussion of halfpence, it seems that Swift’s intention was to convey the impression that the small St. Patrick copper—once a halfpenny—was now passing, some 55 years later, as a farthing. Harris, writing in 1745, further supports this same position by stating:

In this Reign [i.e., Charles II: 1660–1685] were two or three Kinds of Copper Half-pence coined... These afterwards passed

for Farthings, and a large Sort were coined for Half-pence, with this Difference; on the Reverse, St. Patrick standing before

a Crowd of People, with the Arms of the City of Dublin at his Back.57

| 42 |

Simon, Essay, 47.

|

| 43 |

"Historical Account of the Castle of Lea, Queen’s County," from the Leinster Express (1832) at http://www.irishmidlandancestry.com/content/laois/community/lea_castle.htm. Last accessed July 27, 2007.

|

| 44 |

Dolley, "St. Patrick’s Half-Groats and Pennies," 39.

|

| 45 |

C. Clay, Currency of the Isle of Man (Douglas, 1869).

|

| 46 |

Clay thinks this was the 1672 Mic(hael)

Wilson halfpenny of Dublin. See Figure 7.

|

| 47 |

A. Smith, "On the Copper Coin Commonly Called St. Patrick’s," passim.

|

| 48 |

A. Smith, "On the Copper Coin Commonly Called St. Patrick’s," 1.

|

| 49 |

D. T. Batty,

Batty’s Descriptive Catalogue etc, (Manchester, 1886) vol. III, 725–729, describing seven pence and 38 halfpence.

|

| 50 |

Dolley, "St. Patrick’s Half-Groats and Pennies."

|

| 51 |

These comments are either recorded in Aquilla Smith’s paper or come from other footnoted references.

|

| 52 |

Michael J. Hodder, "The Saint Patrick Copper Token Coinage: A Re-evaluation of the Evidence," The Colonial Newsletter 77 (1987): 1016. See also, Colm Gallagher, "The Irish Copper Coinage 1660–1700," NumismaticSociety of Ireland, Occasional Papers 24–28 (1983): 26–27.

|

| 53 |

Authorized patent weight was 110 grains; observed weight was 105 to 199 grains (Mossman, Money, 126, Table 13).

|

| 54 |

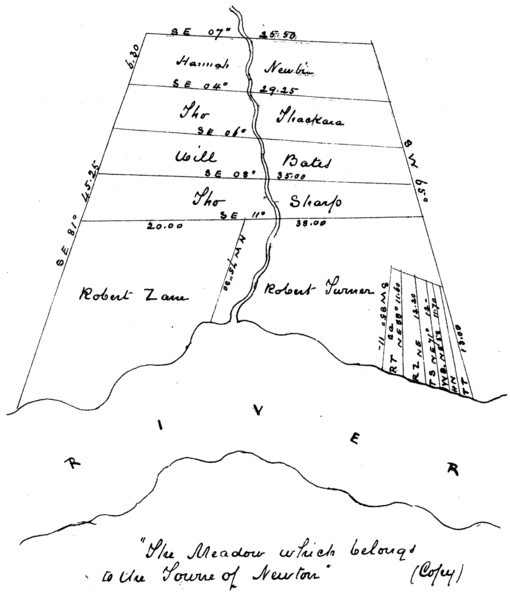

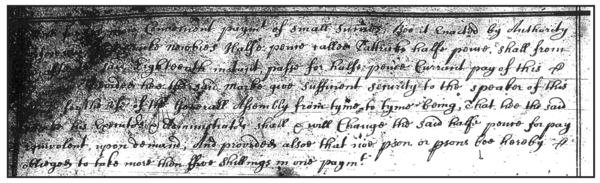

Following the Manx rejection, these unwanted tokens somehow came into the possession of Mark Newby, an English Quaker who was established as a merchant in Dublin where he suffered religious persecution. In 1681, at age 43, Newby and his family emigrated from Dublin to West Jersey and settled in a Quaker community established by William Penn.58 Newby brought with him an unknown quantity of St. Patrick’s tokens. When he was elected to the West Jersey Assembly in May 1682, legislation was soon enacted authorizing his St Patrick coppers to "pass for halfe pence Current pay of this Province" which would be a rate of 24 to the West Jersey shilling, money of account.59 For his tokens to circulate as legal tender, he was obliged to post "sufficient surety" which parenthetically was the same financial arrangement required of John Murrey for his coppers to circulate on the Isle of Man. Being an astute business man, one can speculate that Newby acquired his tokens, probably the small variety, both in bulk and at a considerable discount, which he quickly arranged to circulate in West Jersey as halfpence.60

Crosby cited a reference indicating that many "Patrick half-pence have been ploughed up" on Newby’s original farm.61 Indeed any recovered coppers were halfpence because that was their legal West Jersey rating. Unfortunately the author of this statement failed to note whether the coins were of the large or small variety. None of the large variety traditionally known as "halfpence" have been reported, but to date I have compiled a census of nine small St. Patrick coppers recovered by metal detectors and a single silver coin found in an archeological site in Playwicki, PA. Nothing more is known about the latter.62 Of the small coppers, four were found in New Jersey, and one each in Laurel, MD; New Bern, NC; Greene, NY; Philadelphia; and one near the Massachusetts/Connecticut state line. The Laurel, MD, coin appeared in the Colonial Coin Collectors’ Club Convention auction (November 8, 1997), as lot 309. I agree with the cataloguer’s statement that "No conclusions of any sort can be drawn from an isolated discovery, but it becomes one small piece in the jig saw puzzle of which denomination[s], Halfpence or Farthings, actually circulated in North America."

Figure 10. Norweb gold St. Patrick "guinea." ANS 1988.166.1.

| 55 |

In the original 1724 edition, Swift wrote "passes for a Farthing"; in the 1725 and 1730 editions this was revised to read

"passed for a Farthing," while in the authoritative 1735 version, edited by Swift, he states "passeth now for a Farthing"

(Davis,

Drapier's:

43, n. 43).

|

| 56 |

The 1680 patent is for the regal halfpence of Charles II that was renewed to Knox for the subsequent coppers of James II from 1685–88; both issues of regal halfpence were authorized at 110 grains while the weight for the large St. Patrick copper

I have assumed at 143.5 grains.

|

| 57 |

A. Smith, "On the Copper Coin Commonly Called St. Patrick’s," 3.

|

| 58 |

Mossman, Money, 128–129.

|

| 59 |

Crosby, Early Coins, 133.

|

| 60 |

See also the paper by Siboni and Yegparian in the present volume.

|

| 61 |

Crosby, Early Coins, 135n.

|

| 62 |

Michael Stewart, "The Indian Town of Playwicki," Journal of Middle Atlantic Archaeology, 15 (1999): 48.

|

The Playwicki find provides a natural segue for discussion of the silver St. Patrick coins popularly described as "shillings" (Fig. 9). While little is known about their copper cousins and even less is known about the silver varieties. They were first mentioned in 1697, when Evelyn placed them among the medals of Charles II.63 Thornsby, 18 years later, likewise considered them medals rather than a circulating currency, an opinion shared by both Leake and Harris. This conclusion may have been supported by the fact that they were all minted with a medal turn, although I am not aware of any that have been pierced for suspension.64 Dr. Robert Cane and later James Simon in his 1749 essay considered them shillings struck at the same time as the small copper coins by the Kilkenny Assembly in 1643.65 Currently there are 14 known silver varieties, of which nine were struck from die pairs also used for the small copper tokens.66 Two silver coins are known in both early and intermediate die states, indicating that minting occurred over time.67 Aquilla Smith reported owning three small-sized silver pieces and a "somewhat worn" large silver St. Patrick piece of 176.5 grains that was struck from a pair of dies identical to a pair used for the large copper series. These dies have since been identified as Vlack 1-B.68 Smith concluded that if the small silver coins were shillings, the large one must have been intended as a higher denomination. However, it was his final opinion that all the silver specimens were "model" or proof pieces from the same dies as the copper series. He supported this statement with the fact that he also had a lead proof from a pair of small dies.69

Currently there are four opinions as to the origins of the two species of silver St. Patrick coins: they were either 1) medals, 2) currency coins (shillings), 3) models or proofs of the two copper varieties, or 4) struck much later from original dies, replicating a practice that is well known for Irish gunmoney. To further complicate matters, there are two small St. Patrick specimens struck in gold from different sets of dies. The first, weighing 184.4 grains, struck at an unknown time from genuine dies, recently appeared in the Ford Sale;70 the second is the controversial Norweb plain-edged piece of 125.1 grains struck from 0.917 fine gold using a pair of new and otherwise unknown dies (Fig. 10).71

In returning our attention to the silver St. Patrick coins, I do not know what they represented—but I do know that they were not Irish shillings. Again in the absence of any documentary evidence, we are obliged to turn to the coins themselves to find our answers. I have been able to trace 37 examples ranging from 77.8 to 123.0 with a median of 102.2 grains and an average of 101.5 ± 11.7. Since many of the silver coins were in high grades, it would appear that the intended weight was about 102.0 grains. I do not have a metal analysis to determine silver content, but a single specific gravity of 10.495 is indicative of a high silver content.72

Note that the standard deviation of ±11.7 of the silver St. Patrick coins confirms their wide range of planchet weights. In comparing these coins with other silver coins of the period, it is evident that these planchets did not have the same weight tolerance as those from the royal mints. An analysis of 50 high grade English shillings of Charles I revealed an average weight of 88.7 ± 4.0 grains (range 84.7 to 92.7) for a coinage authorized at 92.9 grains of sterling silver, although some of the sample could have been subtly clipped.73 Even John Hull’s Massachusetts silver shillings of the same period had much less variation in weight than did these silver St. Patrick pieces, suggesting that they were not made in a quality controlled environment such as the Tower Mint. The supposed "Irish" St. Patrick "shillings" at 102.0 grains are 9.1 grains or 9.8% heavier than the English.

Considering that the contemporary English to Irish exchange rate was 100.00:105.56, an Irish shilling should contain 88.0 grains of silver. The average of the 37 examples in this data is 14 grains or 15.9% too heavy. If any shilling of this weight ever hit the Irish shores, its first and only stop would have been the melting pot for reduction into bullion at a handsome profit for the silversmith. As they stand, these "Irish" shillings are actually Irish 14d pieces, a situation that never would have existed.

88 grains ÷12d = 7.33 grains per penny

102 ÷ 7.33 = 13.9–14d Irish

If the coins were below sterling grade they might not be worth as much, but we know how actively the English government resisted any coins that were not 0.925 fine. The best guess is that the silver St. Patrick issues were presentation pieces struck contemporaneously from small copper dies, but were never meant to circulate as currency. Indeed, all this is a guess, since no supporting evidence has accompanied any of the preceding opinions.

| 63 |

A. Smith, "On the Copper Coins Commonly Called St. Patrick’s," 1.

|

| 64 |

One "plugged" example has been brought to my attention, a possible repaired hole, but without any accompanying details. Stanley

Stephens, personal communication, January 10, 2007.

|

| 65 |

Simon, Essay: 48; Smith, "On the Copper Coin Commonly Called St. Patrick’s," 1.

|

| 66 |

Stanley Stephens, personal communications, January. 9–10, and 17, 2007.

|

| 67 |

Personal communication, James LaSarre, May 6, 2006.

|

| 68 |

Stanley Stephens, personal communication, January 9–10, 2007. For the latest Vlack die variety attributions of the large St.

Patrick coppers, see Roger A. Moore, Stanley E. Stephens II, and Robert Vlack, "Update of the Vlack Attribution of St. Patrick

Halfpence with Visual Guide," The Colonial Newsletter 129 (2005): 2921–2928.

|

| 69 |

A. Smith, "On the Copper Coin Commonly Called St. Patrick’s": 5–6.

|

| 70 |

Stack’s Rare Coins,

John J. Ford, Jr. Collection: Coins, Medals and Currency. Part VII. (January 18, 2005), lot 2.

|

| 71 |

Bowers and Merena, The Norweb Collection, part III (March 24–25, 1988), lot 2386. See also the appendix by Robert Wilson Hoge in the present volume.

|

| 72 |

Harrington E. Manville, "Review of Brian J. Danforth’s Paper on St. Patrick Coinage," The Colonial Newsletter 127 (2005), 2783.

|

| 73 |

Weights supplied courtesy of Robert Heslip. In a comment, Louis Jordan notes that "the pyx trial allowed a tolerance or remedy of 24 grains per troy pound of sterling

or two grains per troy ounce of 480 grains, or, about a remedy of 0.387 grain per coin, which is 92.5 to about 93.3; based

on the pyx trial these items may have been slightly worn or shaved. Personal communication, January 8, 2007.

|

In conclusion, I do not think that I have provided any definite answers regarding the intended denominations of the St. Patrick series. However, the following clarifications clearly contribute to our knowledge of the denominations of the St. Patrick series.

For the large St. Patrick copper we can say:

For the small St. Patrick copper:

For the off-metal examples:

If I have failed to answer the question of what the intended denominations of the St. Patrick coinages were, at least I am in good company. Dr. Aquilla Smith, another physician, closed his 1854 paper "On the Copper Coins Commonly Called St. Patrick’s" with the statement, "I now leave the subject open for further investigation." And so do I.

I would like to thank those whom I consulted during the preparation and presentation of this paper including John Griffee, Bennett Hiibner, Michael Hodder, Robert Hoge, Oliver Hoover, Louis Jordan, James LaSarre, Roger Moore, Neil Rothschild, Wayne Shelby, Roger Siboni, Charles W. Smith, and Stanley Stephens. In particular, I wish to recognize Raymond Williams for allowing me to use the data from the elemental analysis of his small St. Patrick coins. Since this article was in a development phase over so many years, I apologize to others who helped along the way whom I may have inadvertently omitted.

Coinage of the Americas Conference at The American Numismatic Society, New York

November 11, 2006

© 2009 The American Numismatic Society

Although the iconography of the seventeenth-century St. Patrick “farthings" and “halfpence" is very rich (Pl. 1–2), it has rarely garnered serious attention from numismatists, and on the few occasions when it has, the results have tended to be mixed. Because of this situation, a number of peculiar iconographic interpretations have evolved in the modern literature as well as within the general lore of the series passed on by collectors. The present paper deals with the interpretive problems of the iconography of the king who appears on the obverse of both series of the St. Patrick coinage. Discussion of the St. Patrick reverse types as symbols of the Protestant Ascendancy appropriated from Catholic sources will appear elsewhere.

It is not infrequently claimed that the obverse type of King David playing the crowned harp on both denominations of the St. Patrick coinage was intended as a portrait of King Charles I, and that, therefore, the series must be dated to the 1640s, or if a Restoration date is accepted, that the coinage was produced under Charles II to commemorate his deposed father. However, a close review of the iconography reveals very little that is distinctly Caroline in the King David type, suggesting that it was really intended to depict David as himself, rather than Charles I as David. This being said, there can be little doubt that the type was intended as an allusion to contemporary English divine-right kingship.

It is interesting to note that while many of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century students of the St. Patrick coinage speculated that the coins were issued or at least used by the Confederate Catholics of Kilkenny in the context of the Irish Revolt of 1641–1652,1 none of them seem to have suggested that the David type was actually a portrait of Charles I prior to Edward Maris’ publication of A Historic Sketch of the Coins of New Jersey in 1881. In this work, the author reported that, “I have been fortunate in securing one of each of the different sizes in perfectly uninjured condition. In the figure representing King David kneeling, I recognize the features of Charles I."2 This view was later endorsed by Walter Breen in a 1968 Colonial Newsletter article and at last canonized for American readers in his 1988 Complete Encyclopedia of U.S. and Colonial Coins. 3 But is it true? Was the face of Charles I actually used for King David on the St. Patrick coinage?

The king’s head, which is only about 5mm from beard tip to crown on the "halfpence" and 3mm on the "farthings," is far too small to distinguish the facial features of Charles I (Pl. 1, 3–4). Thus it seems most likely that the features recognized by Maris in the David type were the pointed beard and shoulder-length hair, rather than the details of the face. There can be little question that the hair and beard of the David figure on the "halfpenny" are reminiscent of some numismatic portraits of Charles I (Pl. 1, 5), but these same features also appear on the portraits of the king’s European contemporaries, such as the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III (Pl. 1, 6), Georg Wilhelm, the Elector of Brandenberg (Pl. 1, 7), and others. More importantly, a similar style of hair and beard is worn by a harp-playing David on a Nuremberg 10-ducat portugaloser of 1641 (Pl. 2, 8). Since a portrait of Charles I is no more likely to appear on a gold multiple of Nuremberg than that of Ferdinand III is to be found on Irish coppers, it seems clear that the beard and hairstyle cannot be taken as personal identifiers of Charles I, and should be understood instead as generic elements of royal fashion in the first half of the seventeenth century.

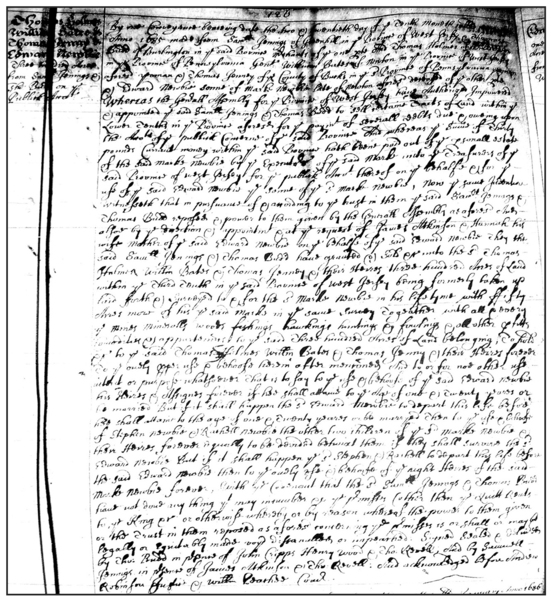

Also problematic for the portrait theory is the fact that the figure of King David on the St. Patrick "farthing" appears to have a different and fuller style of beard and lacks the shoulder-length hair worn by the king on the "halfpenny." The "farthing" type seems to represent King David in old age, with thinning hair and long beard. A similar image of David appears later on the eighteenth-century psalmenpfennige of the Swiss city of Brugg (Pl. 2, 9) and probably derives from earlier artistic depictions, such as "David Playing the Harp" (Fig. 1) by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640).

Breen attempted to support Maris’ dubious portrait identification by citing a remarkable halfpenny pattern made by Nicholas Briot for Charles I (Pl. 2, 10).4 The shorter hairstyle and goatee treatment of the beard actually serve to undercut the portrait argument. King David appears to have longer hair on the "halfpenny" and a full beard on both denominations of the St. Patrick coinage. The main interest here must be the radiate crown, which is indeed very similar to that worn by David on the St. Patrick coinage. However, despite this similarity, there is no evidence that portrait coins depicting Charles I wearing this form of crown ever saw circulation and therefore could have served as a model for David on the St. Patrick coinage. In any case, the radiate crown (also known as the eastern or antique crown in heraldic terminology), like the beard and hairstyle, was not an attribute specific to Charles I, and therefore cannot be taken as proof that David was a representation of Charles I. As part of a continuing Renaissance tradition going back to the Quattro cento, Charles’ contemporaries King Felipe IV of Spain (Pl. 2, 11) and Cnosimo II de’ Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany (Pl. 2, 12) were depicted wearing radiate crowns on coins struck in their Italian possessions as indicators of their classical erudition.5 This form of crown was generally associated with antiquity because it frequently appeared on the Roman coins that were avidly collected by Early Modern rulers.6

In the Roman Empire, imperial portraits wearing radiate crowns were regularly used to indicate double value, as on the brass dupondius (worth 2 copper asses) (Pl. 2, 13) and the silver antoninianus (worth 2 denarii) (Pl. 2, 14), but also became associated with debasement.7 The antoninianus, introduced by the Emperor Caracalla in 213, was rated at 2 denarii and yet it contained only 80% of the silver needed for this intrinsic value. Over the course of the third century, the silver content was increasingly reduced until the antoninianus became a billon coin.7 The fact that Charles I wears not only the radiate crown, but also the draped cloak (paludamentum) of a Roman general clearly signals a Roman model—probably the antoninianus—for this representation. All of his other numismatic portraits depict him in contemporary costume; often involving plate armor with a ruff or lace collar.8 In the case of the Briot pattern, the radiate crown may have been intended to signal the use of debased silver for the proposed halfpenny, lest unscrupulous individuals try to pass it as good sterling. The pattern specimens cited by Peck all have the appearance of silver, but specific gravities that point to the use of impure silver or a base metal core.9 Perhaps most telling against the association between the radiate crowned portrait type of the Briot pattern and King David of the St. Patrick coinage is the fact that this crown form was often connected not only with Roman antiquity, but with ancient times in general. As such, it was not uncommon for the kings of the Biblical age to be depicted wearing a form of the radiate crown in seventeenth century art (Figs. 2–5). As David was one of the greatest of these kings, it is not surprising that he appears wearing this crown in painting (Figs. 2 and 5) and medallic art (Pl. 3, 15), as well as on several series European coins that also depict him with a harp and in a suspiciously similar pose to that found on the St. Patrick coinage. These include the psalmenpfennig of the Swiss city of Bern, struck in the period 1659–1680 (Pl. 3, 16), the quadrupla scudo d’oro of Pope Clement X, issued in 1673 and 1674 (Pl. 3, 17), and the psalmenpfennig of Brugg, produced from 1750 to 1775 (Pl. 2, 9).10 In short, the radiate crown is an expected attribute of David in the seventeenth century and therefore cannot be taken to signal an intended portrait of Charles I on the St. Patrick coinage.