Coinage of the Americas Conference at the American Numismatic Society, New York City

November 4–5, 1989

© The American Numismatic Society, 1990

Classic gold Half Eagles were struck for only a short period from 1834 to 1838. The series consists of the five Philadelphia dates for this period and the branch mint issues from Charlotte and Dahlonega in 1838. The five Philadelphia dates are all readily available—they are frequently offered for sale at major coin auctions and are available at most major coin shows. A date set would therefore be quite easy to assemble. But this series was struck during a period in our history when the coinage dies were prepared individually. During this time the central devices were prepared from a coinage hub but the features around the periphery of the dies were individually punched into the dies. This manufacturing process makes it possible to identify easily the individual coinage dies that were used in the series.

Study of the coins in this series has led to the identification of 21 obverse and 17 reverse dies. Total mintage for the seven dates in the series is just over 2.1 million pieces. This gives an average life of just over 100,000 coins for each obverse die and almost 120,000 coins for each reverse die. Identification of the coins in the series by die variety expands the seven coin series into a fascinating collection of 31 varieties with many interesting and unusual features. Some of these varieties are common and go through a long sequence of die states, while others are rare and represent a challenge to obtain for one's collection. A collection by die variety thus becomes a beautiful historical representation of the gold coinage struck in early America.

These gold coins played an important role in the business ventures of the period and allowed the public to conduct financial transactions more easily. All 31 varieties in the series represent those that I have personally seen and studied over the past few years. The descriptions that are given and the observations that are made in this article were obtained from personal study and comparison of actual coins. While I do not claim that my listing is complete, I feel that my search has been extensive enough to have allowed me to observe all of the common varieties and all but a few of the rare varieties that exist in the series. I have identified the varieties of over 400 pieces at coin shows I have attended, and of over 100 more from photographs that have appeared in auction catalogues. In addition I have studied the 12 specimens from the series that are owned by the American Numismatic Society, the 34 pieces in the National Collection at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., and the 67 pieces in the personal holdings of a New York City collector. Furthermore I have been able to acquire a personal collection which contains examples of 28 of the 31 varieties that I have identified. Of the three varieties that I do not own, examples of two are in the ANS, with the other variety being held by the SI.

The obverse dies for the various dates are really quite easy to identify from a few key features. The central device of Liberty was created from a hub and is nearly identical for all of the obverses. The dates on the various dies were individually punched into the dies and vary considerably in size, style, and location. The date alone is usually sufficient to distinguish the obverse dies from each other, but it is recognized that date positioning might fail to identify some obverses. For positive identification of the obverse, the position of the 13 stars on the obverse periphery was recorded. These 13 stars were individually punched into the dies and their positions vary noticeably among the dies. In particular the position of the outside point of each star relative to the denticles was recorded. Each star is recorded as having its outer point extending out toward the space between two denticles, extending out toward the upper edge or lower edge of a denticle or toward the center of a denticle. These star patterns are sufficiently different that a positive identification can be made when there is any question about whether two obverses are identical. Other characteristics such as the position of the stars relative to the bust or the size of the forehead curl are used when they are distinctive for a particular obverse.

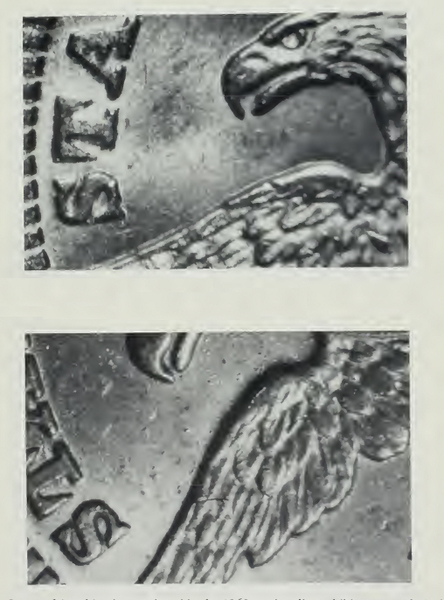

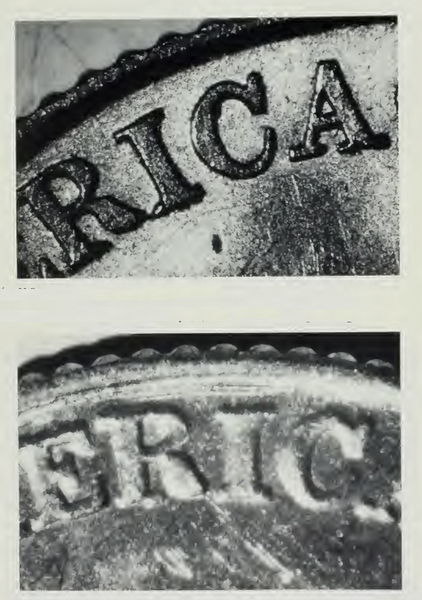

The central device containing the eagle and the shield outline was sunk into the dies as a single unit and is nearly identical from die to die. In contrast the features around the periphery were punched individually into the dies, creating characteristics that clearly distinguish the individual dies. The letters in United States of America vary in relation to each other and in relation to the other devices. The position of the denomination 5D varies with respect to the feathered shaft and the olive stem. The leaves in the olive branch vary in position and size and in their relation to the lettering. Some reverses show a berry in the olive branch and others do not. Some reverses show the eagle with a tongue while others do not. In general, there are enough individual die characteristics to identify positively the reverse dies in the series.

This study is intended to be a preliminary investigation of the classic Half Eagle series to obtain a better understanding of the patterns of die usage during this period. I have refrained from numbering the varieties because emission sequences for the varieties have not yet been established and additions to this list of known varieties are bound to occur once the results of this study become available to the numismatic public. Furthermore no complete description of the individual obverse and reverse dies has been included because new distinguishing features continue to be found as the study progresses. It is hoped that the results of this study will be used as a guide for further studies on the series and serve as the foundation for a comprehensive reference work on classic gold coinage.

There are nine known varieties for this date struck from five obverse and four reverse dies. Reported mintage for this date was 657,460 pieces, the largest mintage for any date in the series.1 Three distinct date styles are known for the five obverses of this date. For the first style the date has a block 8 that resembles two circles resting on top of one another (fig. 1a.).2 The digit 4 is small with a long crossbar that extends out well beyond the right base of the digit. Two obverses have this date style. One has the digit 4 nearly touching the curl while the other has a triple-punched 4 that is distant from the curl. The obverse with the triple 4 is very common and has been seen with three different reverses. The triple image of the digit 4 fades through the use of the obverse die but it can be seen clearly on examples of all three varieties. This obverse also has thin letters in the word LIBERTY on the ribbon that runs through the hair.

The second date style for this year has a script 8 with a thick center that runs at a diagonal downward from left to right. I have called this a "fancy 8" (fig. 1b). This style has a large 4 with the crossbar extending out no further than the right base of the digit. The digit 1 is distinctive in that the upper serif rises sharply to a narrow peak, while the digit 3 has a long center spike that nearly touches the top curve of the digit. Two obverses have this date style. One of these obverses has a digit 4 that is very close to the curl and positioned so that it extends out beyond the left edge of the curl. The other obverse of this style has a digit 4 that is distant from the curl and positioned completely under it.

The third date style for this year has a fancy 8 and a large digit 4 with a large crosslet on the right end of the crossbar (fig. 1c). This obverse was used to strike what has come to be known as the "crosslet 4" variety. This distinctive variety is known to be rare and is one of the few die varieties that has been consistently catalogued and identified in auction catalogues over the years.

Four reverses are known for the nine varieties for this year. The key feature in identification of these reverses is the position of the denomination 5D relative to the feathered shaft and the branch stem above. For each reverse the percentage of the 5 under the feathered shaft and the percentage of the D under the branch stem has been recorded. These percentages are subjective figures since there are no straight lines on the devices from which to reference the readings, but the positions are distinctive enough to identify the reverses in most cases. Other reverse keys include recording whether there is a berry within the leaves of the olive branch and whether the eagle has a tongue.

These features are recorded for the four reverses and produce the patterns given in Table 1. The known die pairs for this date are listed at the bottom of the table. Three of the four reverses used in 1834 have also been identified on coins dated 1835. The only reverse not used in later years is the third reverse with the 5 in the denomination completely to the left of the feathered shaft. It is unlikely that this reverse will be found on pieces with later dates, because it was already badly cracked when it appeared with the third marriage of 1834. This reverse goes through a series of die states with a heavy die crack developing through the base of the letters NITED. This crack later extends to the rim over the U and also extends out to the right of the D. At the present time I consider five of the varieties of this date as common; the four others appear scarce to rare, with the relative rarity among the four scarce varieties still undetermined.

| Obv. Feature | Obverse | Reverse | % of 5 Under Feather | % of D Under Branch |

| Digit 4 80% under curl; 34 close | 1. Fancy 8; digit 4 close to curl | |||

| A. No bud; tongue | 40% | 20% | ||

| Thin letters in LIBERTY; block 8 | 2. Triple cut 4 | |||

| B. No bud; no tongue | 40% | 20% | ||

| Tall upper serif on digit 1; 34 distant | 3. Fancy 8; digit 4 not close to curl | |||

| C. Small bud; tongue | 0% | 10% | ||

| Die crack between S6 and S7 | 4. Block 8; digit 4 just touches curl | |||

| Fancy 8 | 5. Crosslet 4 | D. No bud; no tongue | 100% | 70% |

Known Die Pairs: 1A; 2A; 2B; 2C; 3A; 3B; 3C; 4C; 5D.

There are six known varieties for this date struck from three obverse and five reverse dies. Reported mintage for this date was 371,534 coins. Three distinct date styles are known for the three obverses of this date. The first date style has a block 8 and a short narrow flag on the digit 5 (fig. 2a). The digit 3 also has a short center arc and the digit 1 has a shallow upper serif. The one obverse with this date style dominates specimens of this year. Half of the six known varieties, and nearly 75% of all the coins that I have seen of this date, have this obverse.

The second date style has a block 8 and a long curved flag to the digit 5 (fig. 2b). The digit 1 has a shallow upper serif, while the digit 3 has a long center spike that nearly touches the upper curve of the digit. This obverse appears with only one reverse and this marriage is a rare variety for the year. While this variety is difficult to locate there is a nice example of it in the collection of the ANS and a magnificent proof specimen in the SI. A photograph of this variety is also presented in Walter Breen's encyclopedia.3

The third date style for this year has a fancy 8 and a 5 with a long curved flag (fig. 2c). The digit 1 has an upper serif that rises sharply up to a narrow peak. This obverse has been identified with two different reverses.

Four of the five reverses of this year were used in other years. They can easily be distinguished by the position of the denomination 5D and by noting the presence or absence of a tongue. The third reverse is the only one that was used only for pieces dated 1835 and it is rare.

In fact both varieties with this reverse are very difficult to obtain. The reverse is easy to identify because it is the only one used at the Philadelphia Mint on which a leaf comes up very near to the left side of the U in UNITED. All other reverses of this year have both leaves well below the U. A good rarity estimate for this reverse is yet to be determined, but this study indicates that no more than 5% of 1835 Half Eagles would have this reverse.

| Obv. Feature | Obverse | Reverse | % of 5 Under Feather | % of D Under Branch |

| A. No tongue; no bud | 100% | 70% | ||

| Shallow upper serif on 1 | 1. Small flag on 5; block 8 | |||

| B. No bud; no tongue | 40% | 20% | ||

| Long center arc on 3 | 2. Tall 1; block 8 | |||

| C. Upper leaf not under U | 80% | 80% | ||

| D. No bud; tongue | 40% | 20% | ||

| Tall upper serif on 1 | 3. Fancy 8 | |||

| E. Large bud; no tongue | 50% | 85% |

Known Die Pairs: 1A; 1B; 1C; 2C; 3D; 3E.

There are eight known varieties for this date struck from six obverse and five reverse dies. Reported mintage for this date was 553,147 coins. The obverse dies of this year are difficult to distinguish. Only two date styles have been identified with five of them having the same date punches. The first date style was used on only one obverse and is known as the small date (fig. 3a). For this style the digit 1 is no taller than the other three digits and it has a shallow upper serif. The digit 3 has a long center spike; there is a block 8.

| Obv. Feature | Obverse | Reverse | % of 5 Under Feather | % of D Under Branch |

| Single forehead curl; die crack between S5 and S6 | 1. Digit 6 right of center under curl | |||

| A. Large bud; no tongue | 50% | 85% | ||

| Die crack through S8 through digit 6 | 2. Digit 6 centered under curl | |||

| B. No bud; tongue | 40% | 20% | ||

| Single forehead curl; S13 close to denticles | 3. Digit 6 right of center under curl | |||

| C. No bud; no tongue | 50% | 70% | ||

| Double forehead curl | 4. Digit 6 centered under curl | |||

| D. Small bud; no tongue | 95% | 100% | ||

| S13 close to denticles | 5. Small 1; small date | |||

| Die crack between 83 | 6. Tall 1 low in field | E. Small bud; no tongue | 100% | 100% |

Known Die Pairs: 1A; 2A; 2B; 3C; 4C; 4D; 5D; 6E.

The second date style also has a block 8 but it has a tall 1 that rises well above the top of the other digits in the date (fig. 3b). There is a difference in date positioning for these five obverses, but they are difficult to distinguish in this way. Interestingly, three of these five obverses have strong die cracks; their development through the life of the die can easily be seen on many of these pieces. The first obverse has a die crack that runs between the fifth and sixth stars from the lower left and continues through the curls on the head. The second obverse has a heavy die crack that runs through the eighth star, down through the bust and through the digit 6 in the date. The sixth obverse has a crack that runs through the bust and down between the digits 8 and 3 in the date. These cracks identify many pieces of this year, but star positioning in reference to the denticles is often used for positive identification when no cracks are visible.

The first two reverses for this year were used in previous years, with the last three used only to strike 1836 Half Eagles. Only pieces with the first obverse have proved to be rare, with the other seven varieties all appearing regularly. The fifth reverse for this year has a distinctive feature in that the left edge of the 5 in the denomination is well to the right of the left edge of the feathered shaft.

There are three known varieties for this year struck from three obverse and three reverse dies. Reported mintage for this date was 207, 121 coins, the lowest of the five Philadelphia dates. This date is the rarest of the five Philadelphia issues, and has proven to be more difficult to obtain than the mintage figure would indicate.

The first date style has a block 8 with a tall slender digit 1 (fig. 4a). The digit 7 has a shallow arc over it, and the digit 3 has a short center spike. The two obverses with this date style can be distinguished by the position of the digit 7 relative to the curl. On one obverse the 7 is centered under the curl while on the other obverse the 7 is positioned further to the right and partially below the gap between the curls.

| Obv. Feature | Obverse | Reverse | % of 5 Under Feather | % of D Under Branch |

| Double forehead curl | 1. Block 8; digit 7 right of center under curl | A. Small bud; no tongue | 40% | 85% |

| Single forehead curl | 2. Block 8; digit 7 centered under curl | B. Large bud; no tongue | 50% | 70% |

| Single forehead curl | 3. Fancy 8 | C. No bud; no tongue | 0% | 50% |

Known Die Pairs: 1A; 2B; 3C.

The second date style for this year has a fancy 8, a small 1 with a shallow upper serif and a 7 with a sharply curved upper edge (fig. 4b). The digit 3 has a long center spike that nearly touches the upper curve of the digit. This variety is known as the small date variety for this year.

The reverses of this year can be identified by the position of the denomination 5D relative to the feathered shaft and the olive branch. The three reverses were used only in 1837, each with only a single obverse die as far as is currently known. All three varieties are scarce but the third variety with the small date is the most difficult of the three to locate.

The last Philadelphia Mint issue in the classic series is known in only two varieties struck from two obverse and two reverse dies. Both obverses for this date have fancy 8s in the date but other date characteristics distinguish them. One obverse has a shallow upper serif on the 1 with the second 8 entirely below the curl. The other obverse has a 1 with an upper serif that rises sharply to a narrow peak and a second 8 that is only 80% below the curl and very close to the digit 3 (fig. 5a).

The two reverses of this date can be distinguished by the position of the D under the olive branch. This date has a reported mintage of 286,588 coins at Philadelphia. This issue is considered scarce but I have not found examples hard to obtain. Neither variety can be classified as scarcer than the other, as they have been observed with about the same frequency. So far as is known, each obverse appears with only one reverse. Neither reverse of this year was used to strike pieces of other years.

Coinage of Half Eagles began at the Charlotte branch mint in 1838 and the 1838-C issue is the only classic Half Eagle from this new mint. Mintage for this date is reported to be 17,179 coins, the smallest mintage of any of the classic Half Eagles.

There are two varieties known, both with the same obverse. The one obverse of this date has a different date style from the two known obverses used at the Philadelphia Mint during this year. This obverse has a tall slender 1 that rises up above the top of the other three digits in the date (fig. 5b). The date also has two block 8s, while both obverses used in Philadelphia have fancy 8s. This distinctive date style would seem to characterize the Charlotte Half Eagles for this year and distinguish the obverse die from all others of this year. The C mint mark appears over the left side of the digit 3 in the date about halfway between the digit and the bust.

| Obv. Feature | Obverse | Reverse | % of 5 Under Feather | % of D Under Branch |

| Second 8 80% below curl | 1. Tall top serif on digit 1 | A. Middle arrow shaft broken at first talon | 20% | 70% |

| Second 8 100% below curl | 2. Shallow top serif on digit 1 | B. Middle arrow shaft unbroken at first talon | 20% | 100% |

Known Die Pairs: 1A; 1B.

| Obv. Feature | Obverse | Reverse | % of 5 Under Feather | % of D Under Branch |

| A. Two leaves under U | 40% | 80% | ||

| Second 8 80% below curl | 1. Block 8s in date | |||

| B. Leaf nearly touches U | 50% | 90% |

Known Die Pairs: 1A; 1B.

| Obv. Feature | Obverse | Reverse | % of 5 Under Feather | % of D Under Branch |

| Date doubled at base | 1. Fancy 8s in date | A. No bud; no tongue | 30% | 100% |

Known Die Pair: 1A.

The two reverses of this year can be identified by the leaves in relation to the letter U in UNITED. The first reverse has two leaves well below the letter U. The second reverse has one leaf below the U but the other leaf runs up and nearly touches the U along the bottom of the letter. This reverse also develops a strong die break that runs at a diagonal across the reverse from 2 to 8 o'clock. Both varieties are scarce with the first reverse a little more difficult to obtain. The 1838-C must be considered the rarest in the series today, with most examples being well worn. The SI has four beautiful examples of this date, three of these with the second reverse.

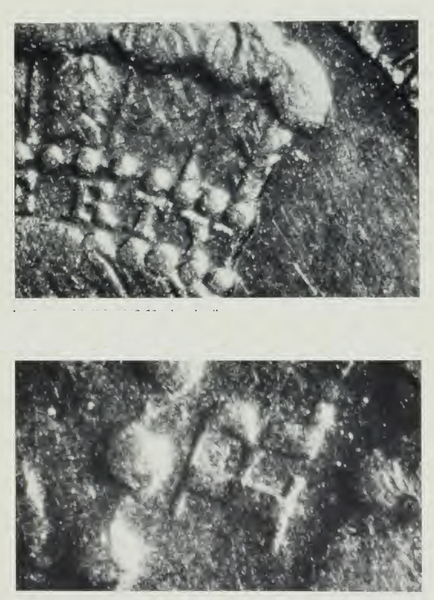

One interesting feature of the Charlotte Half Eagles is the distinctive edge reeding. Examples of the 1838-C Half Eagle have a considerably wider gauge reeding than that used at the Philadelphia Mint during the same year (fig. 6). There are four reeds along the edge of the Philadelphia specimens for every three reeds on a Charlotte coin. The difference is easily observed and adds another distinctive feature when studying genuine Charlotte specimens.

Coinage of Half Eagles began at the Dahlonega branch mint in 1838 with the 1838-D being the only classic Half Eagle from the new mint.

| Date | Mintage | Varieties | Obverses | Reverses | New Reverses |

| 1834 | 657,460 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| 1835 | 371,534 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 2 |

| 1836 | 553,147 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 3 |

| 1837 | 207,121 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 1838 | 286,588 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 1838-C | 17,179 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 1838-D | 20,583 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Totals | 2,113,612 | 31 | 21 | 17 |

Mintage for this date was reported to be 20,583 coins, the second smallest figure for the classic Half Eagle series. There is only one known variety for this date. The obverse has two fancy 8s in the date with the D mint mark over the left side of the 3 in the date and located about halfway between this digit and the bust. While not usually mentioned in auction descriptions, the date on the obverse has the first three digits doubled at the base with an extra upper serif of the 1 showing along the left side of the upright of the digit. This doubling is clearly visible on high grade specimens but fades with circulation wear and is difficult to see on specimens in grades of VF or lower.

This date is the second rarest in the series, with examples coming up more often than the 1838-C date. The average grade for specimens 1838-D is also much higher than for the Charlotte issue of the same year. There are three beautiful examples of the 1838-D in the SI, the best of these being an MS-63. The edge reeding is also wider on the Dahlonega specimens than on the Philadelphia coins of the same year. The Dahlonega reeding matches that of the Charlotte Mint, and again provides a distinctive feature for authenticating genuine specimens from this early branch mint.

| 2 |

Art work for this article courtesy of Lisa R. McCloskey.

|

| 3 |

Walter Breen's Encyclopedia of United States and Colonial Proof Coins,

1722–1989, Rev. Ed. (Wolfeboro, NH, 1989), p. 63.

|

| 1 |

Mintages are cited from R.S. Yeoman, A Guide Book of United States Coins, 43rd ed, Ed.

Kenneth Bressett (Racine, WI, 1990), p. 189.

|

Cory Gillilland

Coinage of the Americas Conference at the American Numismatic Society, New York City

November 4–5, 1989

© The American Numismatic Society, 1990

Marketing strategies used during recent years have prompted the public to purchase United States government-issued gold bullion coins. The bullion coin concept, however, is not so recent or innovative for the U.S. Treasury. The marketing implication, though, has been that these new gold bullion coins which include an indication of their weight and fineness represent an innovative idea on the part of the U.S. Congress and the Treasury Department. That is to say, the idea of issuing a bullion coin was assumed not to have been explored previously by the United States Government.

In fact, more than 130 years have passed since a similar suggestion was made within the financial circles of the government. In 1852 the United States Mint's seventh Director, George N. Eckert, stated in a letter to James B. Longacre, then Chief Engraver of the Mint, that "several mints are authorized to assay, refine and stamp bullion, with the weight and fineness thereof...."1 He then directed that a design be prepared for a bullion disk to be bought and sold by financial traders.

In his communication dated September 4, 1852, Director Eckert also referred to a section of the California Branch Mint Bill (Public Law XXV of the Thirty-Second Congress) which had been signed into law on July 3.2 Although both men were based in the Mint in Philadelphia, Eckert by formal letter asked that the Chief Engraver begin designs for the obverse and reverse of large disks weighing 50 ounces at .990 of fineness. Eckert instructed, "the size of such a disk will correspond to the model in wood herewith presented. Other pieces of 100 ozs & 200 ozs will be issued if practicable & desirable."3

The Mint Director no doubt was aware of the lengthy Congressional debates regarding the then recently passed legislation. Considering them now may help to understand why a bullion coin was considered at the time. After the introduction of the bill in the Senate on December 5, 1851, and the referral to the House of Representatives on December 15, there had ensued heated discussions both in the Capitol chambers and in the press regarding the California Mint bill. On January 7, 1852, the New York City Daily Times printed a report of Secretary of the Treasury Thomas Corwin, wherein he reminded members of the Congress that the distance from San Francisco, by way of the Isthmus of Panama and New York City to the mint at Philadelphia, is 6,250 miles. He referred to the transportation cost of the precious metals found there as a "burdensome tax" levied upon the mining interests in California. Cautioning the legislators, the Secretary stated that the expenses of the Mint and branches had greatly increased since the accession of California, and would be augmented further if Congress should decide to establish two additional branches at San Francisco and New York City. He continued, "I would therefore suggest...the propriety of authorizing a small seigniorage on the bullion deposited by corporations or individuals for the purpose of covering the actual expenses of coinage, instead of allowing the latter to remain as an exclusive charge upon the Treasury." This, he noted, was the universal practice at all other national mints and the charge was but a mere fraction of a per cent, amounting only to a few cents per ounce.4

Congressional debates during the next six months reveal that the Treasury had in mind a charge over and above the cost of assaying the gold. In simple terms they wished to provide for a fee on the actual production of the coinage, a charge for the official government stamp of authority.

Several of the points raised by the Secretary in this report provoked diverse public comments. First of all, the idea that

New York City might become the site of the nation's chief mint caused violent reaction in Philadelphia. On March 4 a resolution of the Pennsylvania Legislature was laid before the U.S. Senate instructing the Pennsylvania Senators

"to vote

against or use all honorable exertion to prevent the removal of the Mint from Philadelphia or the establishment of one in New York City."5 Lengthy rebuttals extolling the virtues of having the mother mint in New York City then appeared on the front page of several issues of the

New York City Daily Times.6 Likewise, the

Secretary's recommendation for the creation of seigniorage caused concern in the national legislature. On June 15 James

Brooks, Representative from New York City, declared to his fellow members

that he felt no more important subject than that of seigniorage could come before the Congress. He defined the term as a right

imposed by the old

European feudal barons as sovereigns, called seigneurs [sic], upon the coinage of their realms. He exclaimed that he could

not comprehend why this seigniorage, this relic of feudal times, was to be imposed for the first time upon the American people.

He explained that

the first bill before the House for consideration would place upon the gold producers a seigniorage charge at the mints. The

cost would be

determined at the discretion of the Secretary of Treasury but would not exceed one per cent. The second bill which had come

from the Senate

without one word of discussion there proposed a seigniorage of one half of one per cent upon all gold or silver deposited

in the mints, whether

coined, or cast into bars or ingots. Mr. Brooks colorfully described his feelings regarding the bills: To levy a

seigniorage, then, on gold and silver now, ...when we are scarce of silver,...is the very error of the moon. A proposition,

under

existing circumstances, more preposterous, as it seems to me, never came from erring man. My resistance to it springs, not

only from the tax

it imposes upon the California miner—for in such a case the miner is the man who pays

the seigniorage if his gold is coined at home—but because the mischievous act would reach our commerce, our freighting trade

at the Isthmus of Panama, our insurance offices, our bullion dealers at home, and send the gold and silver in one continuous,

over-whelming stream to the British Mint.7

Of course, it was not only the California miner who concerned the Representative from New York City. The New York City bankers feared that a large portion of the California gold would be driven to European mints and the conversion to American gold coinage would be greatly restricted—and thus their profitable businesses would suffer.8

In answer to an inquiry concerning seigniorage from the Chairman of the House Committee on Ways and Means, the Acting Secretary of the Treasury, William L. Hodge, explained the practice of the British Mint. He reported that individuals in England did not present their bullion to the Mint as the assay of old bullion was done by private individuals designated by the bank or the Mint. The charge for such was born by the individuals who requested the service. The Bank of England then purchased the gold prepared for coinage at an advantage of three cents per ounce, equal to about one fifth of one per cent of the value. The bank then paid the Mint for the expense of the production of the coinage.9

Since alloying, assaying, and coining of gold is an actual manufacture of a raw material, the Secretary said that he could see no reason why this should be conducted for the benefit of individuals at the expense of the government. If done, he said, like claims could be made by the agriculturist to have his wheat ground into flour"

The Secretary then offered a proposal for handling the current, large amounts of gold at the Mint. Depositors requesting coin bars or ingots would pay less in seigniorage or production cost than if the Mint were to return regular coin to them. The seigniorage charge for ingots of $50 or $100 would be less than the equivalent amount in $20 and $10 coins. The expense to the government would be substantially less if the ingots were made in denominations of $500 or $1,000, or even of larger amounts. The Secretary ventured that probably the depositors would require their bullion to be returned to them from the Treasury in ingots of large denominations. With the mint stamp the ingots would be as valuable and available as coinage.10

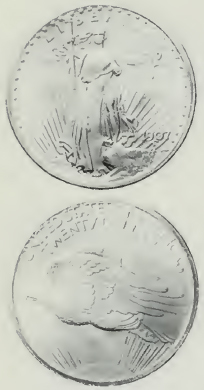

Obviously, the stamp of the official United States Mint was considered by the Treasury Department and the public as differing from that of an Assay Office. The $50 issues of the San Francisco Assay Office (fig. 1) 11 had been mentioned in Congress as "spurious coinage" and in the press as "cumbrous slugs which had excluded the small coin from circulation and had seriously clogged the transaction of business.12

The Secretary of the Treasury felt that public and private banking institutions would prefer the Mint's large ingots over coins since they could be retained in vaults as specie capital. In cases of foreign demand the ingots would be more convenient to export.13

When passed on June 22, 1852, the California Mint Act specified in Section 8 that individuals might request the Mint or its branches to refine and assay gold lumps or dust and cast it into bars or ingots which would be stamped with value or fineness. Fees for such services were to be determined by the Director of the Mint, under the control of the Secretary of the Treasury.14 No reference to seigniorage was included in the final law.

Mint Director Eckert, then only recently confirmed by the Senate, was anxious to carry out this law as he understood it. In his September 4, 1852 directive to Longacre he stated that he intended "to recommend to the department the issue of large disks or coins, of a uniform weight and fineness, with such devises and inscriptions (in addition to the mere statement of fineness and weight) as shall be sufficiently protective of the pieces against fraudulent imitation." He added, "the only inscriptions indispensable appear to be the words 'Mint of the United States. Philadelphia. 1852. Weight ozs. 50. Fineness 990'." It is interesting to note that the Director saw no need to include the denomination; he emphasized weight and fineness.15

Eckert obviously wished to guard against unnecessary postponements. He advised Longacre, "(as it is desirable to avoid delay in the issue)...you will also oblige me by stating within what time such a design could be executed by you.16

Longacre had just been through the ordeal of the 1849 gold dollar (fig. 2) and the double eagle (fig. 3) dies. He had survived his battles with former Director Patterson which had jeopardized his tenure at the Mint. Understandably he was hesitant to set an exact time for the execution of the requested designs and dies. He cautiously responded on September 11 that he had not been able to arrive at a satisfactory solution to the problem of preparing a device for the proposed disks which would be "sufficiently protective against fraudulent imitation." He wrote that an easily executed device appeared to be incompatible with the desired security against fraudulent imitation. What is subtracted from a rapidly executed design, he said, necessarily increases the facility of imitation. "Simplicity in the design is not only admissible but desirable, yet this simplicity often makes the largest claim upon the care and skill, and consequently, upon the time of the artist." He then pointed out other difficulties.

The dies would be much larger in the facial area than those used for the regular coinage of the Mint; yet, "the facilities for working them would not admit of any greater actual relief than that of the smaller legal coins....17

Longacre ventured to suggest a three month requirement for the dies to be completed, but continued to place caveats

upon the requirements. He said time was dependent upon risks in experimentation, facilities, and much needed assistance. With

this long letter he

included four drawings now in the National Numismatic Collection, SI. In the letter, also now in the SI, he described his

drawings: The design

marked No. 1 [fig. 4] is proposed as the obverse: its purpose is to express a representation of America, by a female figure, in aboriginal costume, seated, contemplating one of the usual emblems of

liberty, elevated on a spear, which she holds in her right hand; her left hand resting on a globe, presenting the western

hemisphere. The

whole surrounded by a circle of thirteen stars. No. 2 [fig. 5] is designed as the reverse to no. 1. The device,

the American eagle with his wings [ ] (not legible) and with the Federal escutcheon as usual on his breast: encircled by the

requisite

inscription for the piece. The device for this is more carefully drawn in No. 4.

No. 3 [fig. 6] is a sketch for an obverse of but little ornament, besides the inscription; to be used only in case

No. 1 should be considered too elaborate: for this, No. 4 [fig. 7] would be the appropriate reverse.

My own preference would be in favour of the adoption of No. 1 & 2. Yet it is my duty to state that the execution of these

will in all

probability require considerably more time; than the others.18

Also in the National Numismatic Collection is an ink drawing (fig. 8) presumably by Longacre, perhaps inspired by Eckert though not mentioned in this letter, which provides a sketch for a bullion piece and which is dated 1852. The designs numbered one and two, however, are of greatest interest at this point.

Director Eckert responded to Longacre on September 22. He stated that he felt Longacre had overrated the dangers of fraudulent imitation and had consequently been led to propose complicated designs difficult to execute. Eckert believed that bullion coins would not be as susceptible to fraud as ordinary coins. He stated, "they will not be used for circulation, in the ordinary sense of the word, but will merely be bought and sold as merchandise by banks, brokers, and exchange dealers."

Secondly, "such pieces would not be taken simply on the faith of the impression, but would also be weighed and measured...their genuineness would thereby alone be proved...independent of the Mint stamp." He reiterated, "it appears that a very considerable degree of simplicity is allowable in the devices, and yet these would prove...sufficiently protective against the perpetration of fraud."19

He did not convince the Chief Engraver. Within two days Longacre responded that he did not agree with the Director's prediction for the use of the proposed issue.20 More than a century later it is interesting to note how closely Eckert's thoughts about the function of bullion coins correspond to current commercial practices.

By January 1853, the office of the Secretary of the Treasury in Washington responded to the Mint Director's recommendation. The departmental suggestion relative to the issue of ingots of refined gold was made in a letter dated January 24, 1853. A letter from Eckert dated December 29 was acknowledged in the Treasury's answer as was the receipt of "the accompanying disk in silver of the proposed issue..." Treasury asked "whether it would not be more convenient for the intended purpose if the ingot was issued of the exact value of one thousand dollars instead of the specific weight of 50 ounces." They added that if the Director objected, he had approval to proceed. The silver pattern was said to be returned to Philadelphia with the department's communication.21

On January 27, Director Eckert, writing to Secretary Corwin, said he had already considered the suggestion that the issue should be of the value of exactly $1,000, but the difficulties of such appeared insurmountable or, at least, in need of legislation. "The law, in explaining what gold is equivalent to a dollar, prescribes certain proportions, viz. 9 parts gold, one part alloy of which the silver must not exceed one half. But if the gold is in any different proportion we are not, as I think, entitled to say what it is worth." He then speculated that if the .990 fine disk contained the same amount of fine gold as $1,000 in coin, and if it should be returned to the Mint for coinage, it would be necessary to alloy it with copper down to .900 fine. By so doing, the depositor would be charged the expense of the copper used, and therefore, the value would not be worth $1,000. To avoid such difficulties, he argued that the only mint stamp should be fineness and weight. Again prophetic, he wrote, "Indeed, I suppose that value will be fluctuating, dependent on the demands of the market."22

By February 1853, the correspondence between Eckert and Longacre no longer contained references to gold bullion. Rather, concerns over silver coin designs seemed all consuming.

The following month Eckert resigned his post and by June his successor, Thomas Pettit, had died in office. As if all of this were not enough to make matters at the Mint hectic, the $3 gold coin was authorized by Congress on February 21, 1853.

Longacre was asked to create a design for this new gold $3 coin (fig. 9). The representation of America in aboriginal costume (fig. 10) to which he had made reference in his September 11 letter of the previous year surfaced again. The portrait proposed for the 1854 $3 coin was conceptually an enlargement of the head detail of the seated Indian Princess with feathered headdress which he had suggested earlier for the bullion gold. Longacre could not forget his beauty. Later, when verbalizing his feelings, he wrote, "the feathered tiara is a characteristic of the primitiveness of our hemisphere...In regard then this emblem of America is a proper and well defined portion of our national inheritance...."23 Indeed, his Indian head cent of 1859 became just such a symbol.

The thought that the design for the $3 gold coin had sprung full-blown from Longacre's original ideas without change or modification is not entirely correct. The concept obviously had been brewing in his mind for a number of years. The change from a full length, seated figure to a portrait was an adjustment of necessity. The artistic philosophy of the $3 coin portrait may be traced to the earlier design for the bullion disk.

It is not unusual to find that designs develop in the mind of the artist and then reappear in various renderings throughout a career. The idea that the concept for the $3 feathered portrait of 1854, or for that matter the Indian head cent of 1859, quickly came into existence, unformed and untested in the mind of the artist, is naive. Longacre felt a need to present his own personification of America and he revived the idea whenever the occasion warranted. He appreciated its meaning as did others of a later time. Even after his death, the design was again proposed—as the obverse design on patterns of the 1870s (fig. 11).

The engraver's designs did not disappear; nor was Eckert's vision of a large denomination bullion coin buried forever. There were later attempts made on behalf of the western states to authorize a large denomination gold coin. Legislation for a $50 coin was passed by the U.S. Senate in 1854 but the bill died in the House of Representatives. The idea surfaced again with the 1877 patterns for a gold $50 coin (fig. 12). Both the coin proposed by the 1854 legislation and the later 1877 patterns included an indication of denomination not weight and fineness. The same indication occurred with the issuance of the $50 Panama Pacific commemorative of 1915 (fig. 13). Experiments with commercial, international, goloid, and metric coinage in the 1870s and 1880s included an indication of weight and fineness; but the theory for each differed from that of Eckert. The concept involved the metallic content of coinage or the establishment of an international monetary exchange, not of bullion value.

13. U.S. Panama-Pacific Exposition commemorative $50 gold, San Francisco, 1915.

1 George N. Eckert to James B. Longacre, Sept. 4, 1852, National Archives, Record Group 104, Records of the Philadelphia Mint, "General Correspondence."

In the 1980s the bullion coin idea surfaced again in the Congress and the Treasury Department (fig. 14). Political circumstances permitted a reevaluation of the differences inherent in bullion and regular coinage. Eckert's prediction that origin, weight, and fineness were indispensable indications on bullion coins may now be fully understood. His thoughts that they would not be used for circulation but would be bought and sold as merchandise by banks, brokers, and exchange dealers has been demonstrated.

The success of the Mint's bullion gold program of 1986 is almost legend. Time will tell if the success continues. In 1852 the bullion coin was only an idea ahead of its time. What is yet to be discovered, however, is the fate of "the silver disk" mentioned in the Treasury Department's January 1853 correspondence.

| 1 |

George N. Eckert to James B. Longacre, Sept. 4, 1852. National Archives, Record Group 104,

Records of the Philadelphia Mint, "General Correspondence."

|

| 2 |

The Congressional Globe, vol. 24, part 3, Public Acts of the Thirty-Second Congress (1851-1852), p. iv.

|

| 3 |

Eckert to Longacre, Sept. 4, 1852 (see above, n. 1).

|

| 4 |

"Report of the Secretary of the Treasury," New York Daily Times, Jan. 7, 1852, p. 1.

|

| 5 |

New York Daily Times, Mar. 5, 1852, p. 1.

|

| 6 |

New York Daily Times, Mar. 19, 1852, p. 1; Mar. 31, 1852, p. 1.

|

| 7 |

The Congressional Globe, vol. 24, part 2, pp. 1581-82.

|

| 8 |

The Congressional Globe (above, n. 7), p. 1583.

|

| 9 |

Hodge to the Honorable George S. Houston, Chairman, Committee Ways and Means, U.S. House

of Representatives, June 17, 1852. Cited from The Congressional Globe (above, n.7), p. 1596.

|

| 10 |

The Congressional Globe (above, n. 9).

|

| 11 |

All illustrations are from the National Numismatic Collection, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

(SI).

|

| 12 |

The Congressional Globe (above, n. 7), p. 1598; New York Daily News, Jan. 6, 1852, p. 2.

|

| 13 |

Hodge to Houston, June 17, 1852. Cited from The Congressional

Globe, vol. 24, part 2, p. 1597.

|

| 14 |

The Congressional Globe, vol. 24, part 3, p. iv.

|

| 15 |

Eckert to Longacre, Sept. 4, 1852 (above, n. 1).

|

| 16 |

Eckert to Longacre, Sept. 4, 1852 (above, n. 1).

|

| 17 |

Longacre to Eckert, Sept. 11, 1852. National Numismatic Collection, SI.

|

| 18 |

Longacre to Eckert, Sept. 11, 1852 (above, n. 17).

|

| 19 |

Eckert to Longacre, Sept. 22, 1852. National Archives, Record Group 104, Records of the

Philadelphia Mint, "General Correspondence."

|

| 20 |

Longacre to Eckert, Sept. 24, 1852. National Archives, Record Group 104, Records of the

Philadelphia Mint, "General Correspondence."

|

| 21 |

Hodge to Eckert, Jan. 24, 1853. National Archives, Record Group 104, Records of the Philadelphia Mint, "General Correspondence."

|

| 22 |

Eckert to Thomas Corwin, Secretary of the Treasury, Jan. 27, 1853. National Archives,

Record Group 104, Records of the Philadelphia Mint, "General

Correspondence."

|

| 23 |

Q. David Bowers, United States Gold Coins (Los Angeles, CA, 1982),

p. 223.

|

Coinage of the Americas Conference at the American Numismatic Society, New York City

November 4–5, 1989

© The American Numismatic Society, 1990

These days we are used to being able to pay for a loaf of bread with paper dollars or pocket change—without being charged different prices according to what we pay in; or to take out a loan one day and pay it back in a month or a year without having to worry that for the "greenbacks" we borrowed we might have to repay at face value in gold coins costing far more greenbacks. Few realize how hard-won was this privilege.

A century ago it did not exist. It did not exist partly because nobody knew how to make it happen, partly because many actively opposed it. Those who sought it (the "international bimetallists" and the "free silver" crusaders) represented themselves as advocates of honest debtors (the working poor), but were actually—even if unknowingly—subserving instead the interests of wealthy western silver mine owners. Those who opposed it (the "gold bugs" or gold standard apologists) represented themselves as advocates of honest creditors and entrepreneurs. Many had even grown wealthy from the shifting exchange rates between paper money and silver dollars and gold of the same denominations, or from owning gold mines. Both sides touted their preferred coinage metal as a panacea for the nation's economic woes.

But no matter which side was ahead at any given time, they were playing a zero-sum game: their backers' gain was others' loss, and they wanted to keep it that way. Each side's rhetoric was obfuscatory; even generations later, it has not been easy to tell who were the villains, who the misguided idealists, who the heroes if any. And among the byproducts of their political battles are some of the extreme rarities in American gold coinage—rarities because political factors kept issues limited, or contributed to their disappearance. In their own day, the 1879–80 Stellas and 1879 Metric Double Eagles were "VIP" samples of a diplomat's bizarre proposal for an international coinage that would supposedly end the rivalry of gold and silver (whereas the only real way to do that was somehow to stabilize falling silver prices); today, they are among the most coveted of all numismatic souvenirs of official folly.

This political zero-sum game, this joust between the knights of gold and silver (as Trumbull White called it), was not the intent of the Founding Fathers.1 When Alexander Hamilton devised our national decimal monetary system, he preferred a gold standard as more stable than a bimetallic standard. Gold, as Hamilton believed, was less rapidly and less drastically affected than silver in price or purchasing power by fluctuations in supply: "As long as gold, either from its intrinsic superiority as a metal [i.e. immunity to corrosion], from its rarity, or from the prejudices of mankind, retains so con- siderable a pre-eminence in value over silver as it has hitherto had, a natural consequence of this seems to be that its condition will be more stationary. The revolutions, therefore, which may take place in the comparative value of gold and silver will be changes in the state of the latter rather than that of the former."2 A century later, J.L. Laughlin was still convinced: "Increase the production of gold enormously, and it is eagerly absorbed, and so does not undergo much depreciation."3

Nevertheless, because in Hamilton's day gold was in short supply while Latin American silver was increasingly plentiful, he adopted a bimetallic system as most likely to insure enough specie to run the country: the alternative everyone feared was fiat money, un-backed paper currency, "not worth a Continental," false promises to pay in specie, like the Rhode Island Bills of Credit notes of 1710–86 (fig. 1).

Hamilton's policy could not prevent eventual coin shortages, and the answers included copper tokens and paper. What the states could not legally do, the private sector eventually did, and myriads of types of bank notes passed at discounts if at all, just like their Colonial ancestors. (One wonders if today's advocates of privatizing paper money are even aware of its dismal history.) Many historians, following Sen. Thomas Hart Benton, blamed both the proliferation of paper and the mass melting of gold until mid-1834 on Hamilton's miscalculation of the ratio of gold to silver as 15:1, without explaining what that meant or why.

What it meant was that, following Hamilton's "Report," the Mint Act of 1792 set weight standards for coinage so that a $10 piece would contain 270 gr of gold 11/12 fine = 247.5 gr pure gold, while $10 in federal silver dollars would contain 15 times that weight of pure silver = 3712.5 gr. Sen. Benton thought Hamilton wanted to drive gold out of circulation; evidently Benton had not done his homework. Hamilton's figure in fact agreed with Jefferson's and that in the "Report of the Grand Committee of Continental Congress" (1785), which gave the ratio in France as 15:1, in England 15.2:1, in Spain 16:1. In 1792, the ratio difference was not enough to cause trouble had the Mint become able to make gold coins. What neither Hamilton had anticipated nor Benton recalled was the Reign of Terror (fig. 2).

In 1793, the French Republic under the Terror raised the weight of the Ecu de 6 Livres from 29.488 gm to 30 gm, its precious metal content from 0.8695 to 0.8836 oz pure silver, while setting the gold 24 livres at 7.6 gm containing 0.2199 oz pure gold. This meant 24 livres in silver would contain 3.5344 oz pure silver, for a ratio of 16.07:1. By July 1795, when the Philadelphia Mint began deliver- ing Half Eagles, each ounce of gold, legally worth 15 oz of silver in Philadelphia, would bring 15.5 oz in Paris. Bullion dealers and money brokers (foreign exchange specialists) promptly began buying federal gold coins in quantity at par (probably in Mexican silver, which was legal tender) and shipping them to Paris at a premium.4 Whether from limited mintage or high meltage, early U.S. gold rarities are byproducts of Gresham's Law.

Forgetting the mint's public relations function as a gesture of national sovereignty (it was then under the State Department, not the Treasury), Laughlin even called the mint in its earliest days a failure at keeping the country supplied with small change, "a useless expense to the nation, but a source of profit to the money-brokers." Under the mint's original "free coinage" policy (no seignorage charged against gold or silver bullion depositors) "the possessor of either metal has two places where he can dispose of it—the United States Mint, and the bullion market; he can either have it coined and receive in new coins the legal equivalent for it, or sell it as a commodity at a given price per ounce. If he finds that silver in the form of U.S. coins buys more gold than he could purchase with the same amount of silver in the bullion market, he sends his silver to the Mint to be coined rather than to the bullion market...Having now received an ounce of gold in coin for his 15 oz. of silver coin, he can at once sell the gold as bullion (most probably melting it, or selling it to exporters) for 16 oz. of silver bullion. He retains one oz. of silver as profit, and with the remaining 15 oz. goes to the Mint for more silver coins, exchanges these for more gold coins, sells the gold as bullion again for silver, and continues this round until gold coins have disappeared from circulation... The existence of a profit in selling gold coins as bullion, and presenting silver to be coined at the Mint, is due to the divergence of the market from the legal ratio, and no power of the Government can prevent one metal from going out of circulation."5

Had the brokers and bullion dealers suspected that they were creating instant rarities, they might have squirreled away a few more for their grandchildren; as it was, some evidently did, which explains why proportionately more survive of some low mintages than of neighboring higher ones. Obvious examples include 1815 Half Eagles and 1798 Eagles.

In the long run, the brokers' and bullion dealers' efforts were primarily responsible for destroying over 98% of early American

gold. When people

said that gold vanished by about 1812, they were not exaggerating. Ballpark figures for survivors speak loud and clear:

Quarter Eagles: 1796, over 4% of the original mintage survives (saved as first of their kind); 1797–1833,

mostly 1-2%; 1834 Motto, 0.3% (mostly melted, possibly only a few released to mint officials' friends).

Half Eagles: 1795, over 3% (saved as first of their kind); 1796–1813, about 0.5-2%; 1814, possibly 0.2% (more if some

coins issued that year were dated 1813); 1815, 2% (mostly uncirculated, saved as a seldom-seen date); 1818–33, mostly below

0.1%, some dates

as low as 0.02%; 1834 Motto, slightly over 0.1% (saved as last of their kind).

Eagles: 1795, nearly 3% (saved as first of their kind); 1798, about 2% (mostly in high grades, saved as a seldom-seen

date); others 1796–1803, about 0.5-2%; 1804, slightly over 1%.

In all three denominations, uncertainties in survival proportions arise from uncertainties in mintage figures, which in turn

arise from

unknown quantities of backdated coins.

Why the "endless chain" could continue long after Napoleon restored the 15.5:1 ratio in L'An XI (1803) coinage, why U.S. gold continued to vanish, was not anyone's miscalculation; rather the enormous influx of Latin American silver, which had already begun by 1790 to command lower and lower per-ounce prices in terms of gold, raised (the same thing) the price of gold bullion in terms of silver until gold coins became worth over face. Even if Hamilton had made the ratio match Spain's 16:1, gold coins would still have become worth over face in silver by 1813, when the ratio reached 16.25:1.6

Far from trying to drive gold out of circulation, Hamilton wanted to keep it there for larger transactions, while reserving silver for smaller ones. As Laughlin points out,7 the U.S. adopted bimetallism without prejudice, and its failures were not from sabotage but from economic factors nobody could have foreseen.

Though the Mint Act of June 28, 1834, finally insured that gold would circulate as coin rather than be melted for export, neither this Act nor that of 1837 guaranteed an adequate supply of small change. (Quarter eagles did not qualify as such: each one corresponded to about $50 in purchasing power today.) What circulated instead, then even as decades later, was worn, underweight, mutilated and/or counterfeit foreign silver (primarily Latin American fractions), various kinds of coppers, and, especially after 1837, paper from the private sector: private scrip and bank notes which might be spendable for a discount from face if one was lucky—or be refused everywhere if one wasn't. Arguing that the 1834 Act made debts solvable with 6% less gold than had been due, therefore subjecting all creditors to a corresponding loss, the Supreme Court in 1871 went so far as to denounce the Act as a violation of the Fifth Amendment, as seizing private property for public use without just compensation.8

Paper money had long been a traditional device for financing wars: nominally promises to pay in gold or silver x years after issue, or after the war was won. No matter that Washington's troops defeated the redcoats, the United Colonies lost the economic war with Britain, so that "not worth a Continental" became a catch phrase for over a century, and the Constitution explicitly forbade states to issue bills of credit or to make "anything but gold or silver" (i.e. paper) a legal tender. Though the U.S. won the War of 1812, its small Treasury Notes of February 24, 1815, didn't help the coin shortage. Federal gold coins were still going to melting pots overseas, while half dollars mostly stayed in bank vaults. The small Treasury notes were promptly bought up by fat cats who turned them in for bonds paying 7%. Nor did the later larger Treasury notes help. Those that bore the least interest went back to the Treasury in tax payments; the others were redeemed at maturity. Issued yearly during the Hard Times (1837–43) because the Treasury was nearly broke, and in 1846–47 to help finance the Mexican War, and in 1858–60 again because the Treasury was strapped, they were in denominations of $50, $100, $500, $1,000, and up. Even aside from the interest these notes earned, $50 then corresponded to nearly 2-1/2 oz pure gold, with roughly the purchasing power of $1,000 today (fig. 3).

3. Treasury Note, Act of 10/12/37. $50 (Hessler X99A; reproduced from Hessler, U.S. Loans, p. 122, reduced).

The problem became especially acute in 1861. The Union government's desperate expedients produced long-term effects on gold and silver coinage, unintentionally creating constitutional issues, hardships, and rarities in both metals. Salmon P. Chase, the lawyer Lincoln appointed to finance the Civil War, did so by proliferating fiscal paper in unprecedented quantities: bonds, interest-bearing notes, non-interest-bearing notes, legal tender notes (greenbacks). He tried to extract $150 million in gold from Philadelphia, New York City, and Boston banks for the bonds they bought, but they could not comply, agreeing only to installment payments. His most successful effort was arguably the National Bank Note system: bonds issued under the Act of March 3, 1863, carried a circulation privilege whereby banks could issue NBNs by depositing 90% of face in bonds.

Where Chase's tactics made long-term trouble was legal tender notes (fig. 4). Issuing them meant deciding that Article I, Section 10 of the Constitution applied only to individual states, not to the federal government: "No state shall...make anything but gold and silver a legal tender in payment of debts." As Henry Kissinger put it, "the illegal we do immediately; the unconstitutional takes a little longer."

Legal tender means a form of money that a seller or creditor must accept if offered as payment; if paper is made legal tender, the creditor who lent it cannot legally demand repayment in silver (let alone gold) at face value, nor can the seller refuse such paper in payments for his merchandise. (Imagine today borrowing $100 in federal paper money only to learn on the due date that your lender demands $100 face value in silver, plus interest in silver, and will refuse payment in the same kind of federal paper he had lent.)

After the Civil War, creditors began test cases of the issue: how can fiat paper money be legal tender under the Constitution? The Supreme Court waffled forth and back for years. The underlying agenda: wealthy lenders wanted to retain the privilege of lending greenbacks and demanding payments and interest in gold at face value, knowing that the gold would buy more than its face value in paper, when it could be had at all—greenbacks had driven gold out of circulation, creating more rarities. In 1866, for a $10 greenback one received only $6.60 in gold; in 1875, still only $8.70. The creditors feared "cheap money" and "scaling debts": specifically, that dishonest debtors would repay at face value in discounted greenbacks, or after 1876 in silver coins which had cost maybe 60% of face value in greenbacks; they believed that debtors were not honest working people but unwise land speculators. The debtors feared "dear money": specifically, that creditors who had lent them discounted greenbacks (or, later, silver) would demand repayment at face in gold which might cost nearly double face value in greenbacks or silver; they believed that creditors were not honest entrepreneurs but speculators and market manipulators. The term usury became common in street talk and editorials; the issue even contributed to anti-Semitism.9

"Here I hold up to view the fraud of the system; how increase in the value of money robs debtors. It forces every one of them to pay more than he covenanted to pay, not more dollars but more value, the given number of dollars embodying greater value at the date of payment than at date of contract. In these days debtors must struggle hard to be able to pay what they honestly owe. A money system which forces them to pay from 10 to 50% blood money is devilish indeed."10

This kind of creditor unfairness was legal so long as the Supreme Court did not rule definitively that Salmon P. Chase's greenbacks were legal tender no matter what the Constitution said. And the issue made many lenders very wealthy, many more borrowers poorer. One does not have to be a Marxist to recognize that this led to social unrest.

First the gold vs. greenbacks issue, then (after the 1873–77 depression and the Specie Resumption Act) the gold vs. silver payments issue, produced opposing ideologies—belief systems with much in common with religious cults, intolerant of doubt or deviation, defended with moral arguments, total passion, and total misunderstanding. The gold/silver rivalry dominated presidential campaigns from 1876 to 1900, climaxing in 1892 and 1896, by which time everyone had taken sides. Richard Hofstadter called it "money mania."11

On the comparison with religions, recall what Senator Henry Fountain Ashurst, Democrat of Oregon, told Treasury Secretary Morgenthau: "My boy, I was brought up from my mother's knee on silver, and I can't discuss that with you any more than you can discuss your religion with me." Hofstadter comments: "On the moral side, the defenders of the gold standard often seem as dogmatically sealed within their own premisses as the most wild-eyed silver men, and usually less generous in their social sympathies. The right-thinking statesmanship of the era, like its right-thinking economics, was so locked in its own orthodoxy that it was incapable of coming to terms in a constructive way with lasting and pervasive social grievances. The social philosophy of J. Laurence Laughlin and the statecraft of Grover Cleveland cannot, in this respect, command our admiration. They accepted as 'natural' a stark, long-range price deflation, identified the interests of creditors with true morality, and looked upon any attempts to remedy the appreciation of debt as unnatural and dishonest, as a simple repudiation of sacred obligations."13 Laughlin, debating with "Coin" Harvey, denounced the silver ideology as "an attempt to transfer from the great mass of the community who have been provident, industrious, and successful, a portion of their savings and gains into the pockets of those who have been idle, extravagant, or unfortunate."13 Even Allan Nevins, who admired Cleveland's defense of the gold standard, said that "our history presents few spectacles more ironic than that of our Eastern creditors taunting [debtor farmers] with dishonesty while insisting on being repaid in a dollar far more valuable than had been lent."14

The disease was falling prices, falling real wages, falling purchasing power of the silver in which one was paid. Harder work and savings were not paying off; the working poor were in fact becoming poorer, the rich richer as their gold kept rising in purchasing power.

The cause of the disease, even as 60 years earlier, was oversupply of silver. Not merely the output of western mines, but U.S. silver coins of 1853–62 returning in 1877 from Latin America where they had circulated during and after the Civil War.15 Compared to gold, the price of silver continued to fall no matter what financiers or governments did, no matter how many tons of silver the Mint Bureau had to buy from western mine owners to make Morgan dollars.

Among those who did not understand the cause, conspiracy theories abounded, even forming part of the Populist party platform in 1892. Their villains were largely London bankers and any other bondholders and speculators who might gain from damaging the U.S. as a competitor. This fit only too well the agenda of nativist and isolationist ideologues, for whom Anglophobia was a way of life; one was either for them or one was for the Enemy.16

5. Jim Fisk, 1. (Union Club Library Collection, New York City, reproduced from John Steele Gordon, The Scarlet Woman of Wall Street [New York City, 1988], p. 132); Jay Gould, r. (reproduced from Harper's New Monthly Magazine, Nov. 1885, p. 852).

It became harder to dismiss conspiracy theories after the actual 1869 conspiracy of Jay Gould and Jim Fisk (fig. 5), who tried to corner the gold market and almost succeeded. Two years earlier, they had escaped to New Jersey with $6 million cash from printing and selling counterfeit Erie Railroad stocks. Gould bribed the New York City legislature to legalize the fake stocks, and with his $23 million profit he bought the Union Pacific Railroad, the New York Elevated Railroad, and Western Union. Gould and Fisk then tried to buy up the entire $15 million of gold coins then in circulation, after which they could raise gold prices as high as they chose. They almost made it, but President Grant ordered the Treasury to start selling federal gold in bullion markets. Some of Gould's Administration spies (including Grant's brother-in-law) leaked news of this decision. By the time Grant's action ("Black Friday," September 24) lowered gold prices, Gould had cleared $11 million profit, with chaotic effects on world markets.17

Doubtless this real-life example was in the mind of such free silver paladins as William Hope Harvey, when they kept reminding everyone that the entire quantity of circulating gold could fit in a 22-foot cube: though Gould and Fisk had lost, others might win.18

Something had to be done. Those who spoke for all sides thought the answer was pressuring Congress to enact laws to cure the symptoms, the cure differing along party lines. On the left, radical Populist free silver (with 40% of the votes in the Congressional election of 1894); in the center, liberal Democratic international bimetallists; on the right, conservative Republican gold bugs. These alignments set the rich older generation against the struggling young; east coast financiers against western farmers; capital and management against labor; and creditors against debtors.19

To understand the alignments and the arguments one needs to recall some features of nineteenth century monetary theory, based on the notion that money meant precious metal by weight, and that fiscal paper ultimately represented promises to pay in precious metal.

Laughlin gives three major functions for money, of which only the third is strictly relevant to the 1876–1900 bimetallism issue. Money, for Laughlin, serves 1) to transfer value; or 2) to compare value (as a common denominator more efficient than barter); or 3) "as a standard of deferred payments." Especially in senses 2) and 3), the value of anything (including gold or silver) is a ratio, unstable, changing as either numerator or denominator changes, whether you price silver in terms of gold or vice versa, or dollars in terms of marks or vice versa. Then, nearly everyone believed the ratio had been stable in earlier generations before unwise governments and ungodly financiers tampered with it. Today we know that stability is a Golden Age illusion, that fluctuations have been chaotic all along, and that when an extraordinary increase occurs in silver, gold or another high-demand commodity, the effects are faster and wider fluctuations; and in storm-tossed tides of shifting prices, buyers and sellers alike can drown.20

Bimetallism's chief aim was ostensibly "to secure, as its advocates claim, a less changeable standard for paying long [installment] contracts, and to accomplish this, an international league is indispensable to even a shadow of success" (as Hamilton had recognized a century earlier). Departing for once from the standard gold bug line, Laughlin said "the highest justice is rendered by the state when it exacts from the debtor at the end of a contract the same purchasing power which the creditor gave him at the beginning of the contract, no less, no more."21 But note that he ignored shifting interest rates.

Bimetallism of the more radical or free silver variety (the only kind with which the U.S. ever experimented) was always vulnerable to foreign ratio changes, to bullion speculation, to other market manipulation, and to new discoveries of either metal, historically silver being more affected than gold by this last. Unstable gold/silver ratios were always dangerous, though effects were cumulative over years, so that many did not recognize the connection between an 0.25% shift in the ratio and a lowering of real wages in factories a few months or years later; or between the issue of coin notes mandated by the 1890 Sherman Act and the Panic of 1893.

Free silver was always an oxymoron; its real name was unilateral national bimetallism, meaning reversion to the Mint's 1795–1834 policy but with slightly lighter silver dollars. Free silver actually meant the legal right of any private owner of silver bullion to take it to one of the mints and have it made into coins without paying high seignorage. "Through it alone can Gresham's Law have an immediate effect." It was the law of the land until 1853. Free silver champions, notably Harvey, insisted that the U.S. should return to the old policy no matter what other countries might do: a position near to isolationism. Advocates less rational than Harvey insisted that God created the gold/silver ratio and that humans disturb it only at peril.22

Possibly the later developments can be understood most easily by focusing on a few crucial events and on how stupidity on gold and silver sides led to catastrophe in 1873–77 and again in 1893–96. A full treatment of the problems would be book length.

Though the Comstock Lode and its 1870s near kin were short-term local benefits, they were long-term national disasters. Their eventual effects on silver prices expressed in gold were similar to those of the Latin American mints 80 years before. Their discoverers fared no better than John Marshall at Sutter's Mill; cheated out of their claims, they died poor. The more silver the Nevada bonanzas produced, the less it was worth per ounce, the more the New York City financiers' gold holdings rose in purchasing power, and the more desperate the farmers whose cotton and wheat sold for less and less in purchasing power. More than Bryan realized, more than McKinley cared, more than either of them could have understood, nearly any circulated common U.S. gold coin ca. 1879–1900, if it could talk, could tell stories of agony about the ones who had to spend it rather than stash it. The uncirculated ones spent most of their time in financiers' vaults, as silver dollars did in the Treasury.

Not coincidentally, in 1871, the German Empire adopted the gold standard, using the $1 billion in gold extorted from France after the Franco-Prussian War (equivalent today to $20 billion). Sen. George Graham Vest, Democrat of Missouri, arguing against the Sherman Act, said the Empire went to gold because Britain had prospered from it since 1844.23 Germany dumped thousands of tons of silver on the market. Prices of silver began falling in terms of gold; prices of gold began rising. Some silver advocates blamed German silver sales for the depression of 1873–77; though not the whole cause, German policies certainly contributed to it.24

By omitting the old-tenor silver dollar, the Mint Act of 1873 automatically defined the coinage unit as gold and made all silver coins subsidiary, their face value enough above bullion value to keep them in circulation rather than melting pots. Contrary to how partisans interpreted the Act's name of "Crime of '73," its real crime was in making trade dollars legal tender.25 Silver crusaders wrongly blamed the Act for the Panic of '73, beginning September 18, when "the leading American banking company, managed by government agent Jay Cooke, suddenly declared bankruptcy." By September 30, the New York City Stock Exchange closed; by December 31, 5,183 businesses (then worth over $200 million) failed. Other causes contributed, notably the Great Epizootic of September 1872, a mosquito-borne virus which that fall and winter killed some 4 million horses in many of the nation's largest cities, stopping deliveries of mail, goods, and funds, public transit, garbage collection, and firefighting—leaving many homeless after the fires.26

In July 1876, the value of silver collapsed. Trade dollars, though demonetized by joint resolution of Congress on July 22, came back in immense quantities to California. During 1877–78, over 8.6 million of them circulated in the east. Employers bought them in quantity at bullion value (80-83¢ each) and put them into pay envelopes at $1 each; company stores raised prices accordingly, or else would accept them only at bullion value. Many petitions reached Congress asking for recall of trade dollars; others sought restoration of their legal tender status.27

Meanwhile the Act of February 28, 1878, mandated monthly Mint Bureau purchases of $2-$4 million in domestic silver bullion for coinage only into silver dollars, pleasing nobody but the mine owners. Three of President Hayes's main reasons for vetoing the bill amounted to this: by making silver dollars receivable for duties, U.S. gold revenues would be cut off, and the Treasury would not be able to fulfill commitments to bondholders, i.e. pay them off in gold as promised.28 Nevertheless, Congress passed it over his veto. Carothers justly characterized this Act as "a wretched compromise, without a single redeeming feature, carrying with it the dangers of a wrong-ratio bimetallism without establishing the double standard. By it the silver mine owners were bought off with a large market for silver, the bimetallists were deceived with fictitious restoration of the double standard, and the gold standard advocates were solaced with a last minute rescue of the gold standard when it appeared to be doomed."29

In 1878–79, Hon. John Adam Kasson (then Minister to Austria-Hungary) proposed that the Mint use one or another version of Wheeler W. Hubbell's goloid alloys to make coins intended for international circulation; goloid and goloid metric dollars; Stellas; and metric Double Eagles (fig. 6). Supposedly the goloid (silver with about 4% gold) and metric gold (containing 10% silver) would end the rivalry. How could such coinage proposals ever have had more than symbolic effects? How could anyone ever have imagined they could affect falling silver prices and rising gold prices? Nevertheless the Mint made the sample coins, and a congressional committee reported favorably on the proposal, but no authorizing act followed. The dollars went to collectors; the Stellas to congressmen and other favored parties; the metric Double Eagles to a few VIPs. Today they are expensive curiosities.

The Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890 did not help free silver's repute; after it, the common people were hurting worse than ever. Under it, each month the Mint had to buy 187.5 tons of new domestic silver bullion, paying in Coin Notes (Treasury Notes of 1890 [fig. 7]), which the mine owners promptly turned in for gold, some of which went to buy more bullion to resell to the Mint at a profit—another endless chain. The Coin Notes they turned in were reissued, each eventually removing many times its face value in gold from circulation.30 While Treasury vaults bulged with silver dollars which circulated little and bought less than greenbacks, the gold reserves sank below the $100 million required by the Act of July 12, 1882. Many feared that greenbacks would no longer be redeemable in gold, or that the Treasury would default on foreign debts and domestic bonds payable in gold.31