In submitting a new classification of the issues of Metapontum there should be slight need for an apologia, but it may not be obvious why a study of the coinage of this city has greater urgency than have those of most of the other Greek cities. Many city-states have had an uninterrupted coinage extending over more than three centuries, and of their history we know just as little or even less. Few, however, have coins possessing so wide a variation of obverse types. This consideration is of the greatest importance because the badge of the city, the barley ear, which occupies the reverse throughout the double-relief coinage, is so distinctive through symbols and style, that the combinations with the changing obverse types—the so-called muling—enables a close approximation to the chronological order in which these types appeared. This peculiarity is the strongest reason for giving the coinage of this city our attention— but there is the greater incentive because previous efforts in this direction have not been instituted since the introduction of photography. Carelli1 and Garrucci2 used engraved plates which record many inaccuracies. The British Museum Catalogue for Italy was among the first of that series, but it is without the photographic plates which aid in making the later volumes such treasure-houses of facts. The sequence of Tarentum's "Horsemen" has been worked out by Sir Arthur Evans, but Tarentum was the only Dorian Colony in South Italy, whereas Metapontum, like the others, is Achaean.

Fortunately there is no question concerning the location of Metapontum. Strabo's account3 is free from ambiguity, and the remains of a sixth century Doric temple4 of which fifteen columns are still standing leave no room for further questioning. Excavations conducted by the Due de Luynes in 1828, and published by him in a thin elephantfolio,5 offer further confirmation of what little literary evidence we have. The identification of a second Doric temple, through a dedicatory inscription, as sacred to Apollo (Lycaeus?) is of first importance.6 This second structure is thought to date from the end of the sixth century, and lies within the walls of the town, which have been traced for some distance. The sites of the Agora and of a theatre were established, and give indications of the importance of the city. There are also remains of an artificial harbor7 of moderate size, as well as traces of what has been considered an ancient canal feeding into this harbor. If the belief that this was a canal is warrantable, there would be room for thinking that irrigation may have played some part in developing the agricultural wealth of Metapontum.

Metapontum today is hardly more than a railway station at the junction of the lines from Potenza and Reggio to Taranto. The plain has been over-run with sand and is partially covered with scrub-growths. The dangers of malaria during summer make spring and the late fall the best times for visits. There is no need to doubt the accounts of the extreme fertility of this territory at the time of the city's founding, for the change would be amply accounted for by the deforestation which has taken place since then. This would apply to the upland as well as to the plain, and with wooded slopes to retain the rainfall, there is every reason to credit the early accounts of the attractiveness of the district. The site lies on the coast between two rivers—the Casuentus on the west and the Bradanus on the east, and is nearest the latter, giving point to Strabo's observation that its recolonisation from Sybaris after the destruction of the earliest settlement by the "Samnites" was for the purpose of opposing the spread of the influence of Tarentum, something less than thirty miles distant. The Bradanus thus offers one line of defense, but save for the difficulty of a surprise attack over the surrounding plain, there were few other advantages of a defensive nature. A small, but excellent map, is to be found in Baedeker's "Southern Italy".

The literary sources for the history of Metapontum afford but little help. Strabo records of the city that "they so prospered from farming, it is said, that they dedicated a golden harvest at Delphi." This has frequently been interpreted as a counterpart of the badge of the city, in gold— or possibly a sheaf of golden barley. R. Egger8 offers reasons for thinking that the offering consisted merely of a holder in which some twelve or more golden spears of barley were fixed. The reproduction on page 9, for permission to use, which I am indebted to the kindness of Dr. Jacob Hirsch, shows an offering of wheat ears which is believed to have come from Syracuse. Save as indication of Metapontum's prosperity, we obtain little aid from this passage.

At Olympia there was a "treasury" belonging to the Metapontines, and this has been given perhaps undue weight (cf. Nissen9 et al.) in having been accepted as a further indication of the wealth of the city.10 That these treasuries had in measure some such connotation is undeniable, but Dyer11 has shown that they are to be considered communal houses rather than places in which to store costly gifts or offerings. For this reason, that the treasury of Metapontum at Olympia was associated with those of such cities as Sybaris, Megara, Syracuse, Gela and Sicyon is stronger testimony of Metapontum's importance than that it should have filled such a structure with "treasure".

Wheat-ear of gold from Syracuse.

Pythagoras was received with honor at Metapontum after having fled from Croton, but little can be deduced from this. Nor can we gain a great deal from the statement that Metapontum sent two ships to the aid of Athens against Syracuse,12 unless we are to adjudge this number as either the maximum possible or the minimum they were willing to risk. So too with the reference to Aristeas,13 although this may have a bearing on one of the coin types, as we shall see later.

An effort to visualize the status of these Achaean colonies before B. C. 510 should prove suggestive.

The size and wealth of Sybaris must have given that city a predominance over her neighbors, some of which were, like Metapontum, founded by her. If we seek the foundation of the growth and wealth of Sybaris in her commercial relations, it is fairly obvious that her land-trade must have been of greater importance than her traffic by sea. Her pre-eminence has been attributed to having control over the shortest and easiest of the routes between the Ionian and Tyrrhenian Seas, over the narrow instep of the great boot of the Italian peninsula.14 Trade rivalry with Siris, a city controlling a rival trans-isthmus route, is usually accepted as the reason for the destruction of that city at the hands of Sybaris, Croton and Metapontum—although this may not have been the sole cause. It is entirely possible that the demands of her Etruscan and other markets on the Tyrrhenian shore absorbed the entire supply of what Sybaris had to offer, as well as other commodities purchased from the Achaean cities—such as grain from Metapontum—material which Sybaris could transport over the shorter road within her control more economically than any of her neighbors.

Miletus was in close relationship with Sybaris, and there is evidence that this had some commercial basis. Whether it was sufficiently extensive to give Sybaris any considerable advantage as an entrepreneur is not apparent, but whatever the commodity, Sybaris had a double market—her Greek neighbors and the Etruscans. Furthermore she was able to prevent the latter, and in all probability the Greeks as well, from having direct contact with Miletus, and thus could exact a double profit on a single transaction. Speck states that the woolen fabrics of Miletus were exchanged for grain.15

Save for the Milesian and other Ionian cities, and with the important exception of trade among themselves, which must have been considerable, the only sea market open to these Greeks of South Italy would have been the mother country. The Achaeans were a farming rather than a maritime people, and this characteristic the colonies shared. None of them possessed a large natural haven— Tarentum was Dorian, and controlled the only secure harbor. Sicily and the straits of Messina were in the control of the Chalcidians, and the Adriatic was under the sway of the Corinthians. The size of the ships and the consequent smallness of their cargoes would necessitate the carrying of some commodity of high value within small compass before its worth would be such as to exert much economic pressure. The income of these cities must therefore have been from their landward side. It would not be surprising to have archaeologists at some future day find evidence that there was mineral wealth in these mountains—Lenormant states that silver mines were operated in southern Italy up to the time that the discovery of America's store made their operation no longer profitable.

The fall of Sybaris brought many important changes. It is hardly likely that any of the other cities could have continued the contact with the Milesian market, and only sixteen years intervened before Miletus fell to the Persians. The sheltered position of South Italy during the period the Greeks were fighting the hosts of Darius and the Sicilians the Carthaginians, has slight bearing on the period of the incuse coinage. Before passing to the issues of Metapontum, it is desirable that we examine the coinage of this group of cities to see what evidence their money may have for their history.

The fabric of the incuse coins used in common by almost all of the Achaean cities before the fall of Sybaris, was accepted by Lenormant as cause for thinking that there must have been a monetary confederation, and the issues in this form of Dorian Tarentum and Chalcidian Rhegium—trade rivals of the other cities—did not deter him. Dr. George Macdonald has shown,16 however, that there are other serious objections, the chief of which is the variation in the weight standards within the presumed confederation. He seeks an explanation in some practical consideration— adopting Mr. Hill's idea that the form may have been dictated by a desire to stack or pack the coins.17 The difficulty in the way of accepting this will be evident if one tries to "stack" even a few of the staters of Sybaris or Metapontum—they form a very unstable column. Is it possible that we may find some better and more practical explanation ?

What has been said of the preeminence of Sybaris, at once suggests the probability that this city was the originator of the incuse fabric. Metapontum and Poseidonia were both colonies of Sybaris, and it is hardly likely that they would have instituted the form. Croton or Caulonia might have initiated this style of coining, but neither were of a size or importance to have their practice seized upon by their so much larger neighbor. It seems, strangely enough, to have been a spontaneous invention and to have been evolved without any evolutionary development. Mr. Head's position18 that the swastika-incuse issues of Corinth were used as a model does not carry full conviction. Possibly the trade relations between Magna Graecia and Corinth may have brought the germ of the idea, but the hiatus between the two forms is too great to say that the one is derived from the other. We have one of these Corinthian issues used for the flan of a late Metapontum stater of the thickened type which must have been struck about 490 B. C., and the idea that it had been the pattern would imply that the Corinthian piece had been in circulation more than sixty years before restriking. Having only the slight value which attaches to negative evidence, is the circumstance that these pieces have seldom or never been found in hoards unearthed outside Italy. This carries the suggestion that the consideration of preventing the export of money and, consequently, of restricting its circulation to South Italy must have been prominent in the minds of those responsible for originating the form. Again, we rarely find these incuse pieces overstruck. Any attempt to attribute the form to Pythagoras will have to take into consideration that he must have left Samos a fairly considerable number of years after the earliest issues.

There is one circumstance in this incuse coinage as a whole that is of help in our study of the issues of Metapontum. It affords in certain cases a parallel evolution, but Croton alone covers satisfactorily the same period as Metapontum. The destruction of Sybaris in 510 is invaluable as a dating criterion. Up to that time, the coins of Sybaris were of the wide, thin flans, although examination reveals a barely perceptible diminution in the size of the flans, but, more particularly, in the size of the dies.

We should be under no illusion that we have a complete or even an approximately complete series of these incuse coins. The next hoard of them that is unearthed will, doubtless, provide pieces from dies whose like has never been seen before. It follows almost without saying, therefore, that there can be no claim to completeness for this material, even though we try to record all the varieties at present in cabinets devoted to Greek coins.

Whether what we now have sufficiently approaches completeness to permit a probable reconstruction of the coinage of Metapontum, is quite another question, the answer to which is obviated by the fact that we must obtain what benefit we can from the facts in hand. Should additional facts at some future time make rearrangement of this material necessary, it will have provided in the meantime means for the identification and, perhaps, for the further classification of the issues of this city.

Turning to the coins of Metapontum, in the light of the evidence afforded by the coins themselves, it is at once apparent that they are struck from a pair of inter-locking dies. The cutting of the obverse die would be comparatively simple. It is in the reverse die that difficulties are met, and this is due especially to the circumstance that the ear is in such high relief. In some of the specimens, the high point of the middle row of grains is 4 mm. from the field. If the reader is interested in the technical discussion which follows, he will be greatly aided by taking one of these incuse staters and making an impression of the reverse in sealing wax or any soft modeling wax or plastolene. Failing that, if he will take one of our plates and conceive of the lighting for the reverses as coming from the direction opposite to that actually used; through an optical illusion the reverse of the coin will appear as though in relief and consequently like the die itself. He can then follow the argument with sufficient closeness.

To cut the reverse die directly, the die-cutter would have had to remove the entire surface of the die, with the exception of the ear itself and the rim, and he would have had to cut to a depth equal to the relief of the highest point of the ear. In other words, about three-quarters of the surface to a uniform depth of nearly 4 mm. would have to be removed and all of the delicate portions of the relief would have to be left untouched, including the rim as well as the awns. This feat is not impossible, but that it could have been carried out for so extended a coinage without having left some traces is almost inconceivable. Was there any other manner of preparing the die which was open to our artist?

We know very little about ancient dies, especially Greek ones, because almost none that are above suspicion have come down to us. Mr. G. F. Hill, in a very carefully thought-out article on ancient methods of coining,19 summarizes the evidence to be drawn from them. We do not know whether the ancient dies were of steel or of bronze hardened in a manner with which we are not acquainted, and as much depends upon knowing this, our reasoning has to be speculative. It seems probable that some method of hardening the dies was known, just as some method of annealing the silver flans to be struck seems to have been practiced. The circumstances because of which it is impossible to believe that the reverse dies were cut directly at Metapontum, i.e., in relief (cameo) have just been cited. All of these difficulties would be eliminated, however, if what is known as a "hub" in the making of modern medals were used. From the hub, which is the negative of the die, a die can be struck and hardened. Being the negative of the reverse die (which we have seen is in high relief), the hub for this reverse would have to be cut intaglio, just as the obverse had been and as all the gems of this period were cut. If tempering was practiced, the obverse die and the reverse hub would be cut intaglio in the untempered metal and later hardened. Into this hardened hub, the reverse die, probably in a heated state, would have been driven. The die so obtained was then finished and after hardening was ready for use.

If the reverse die was forced into a "steel" hub in a heated state it would have "drawn the temper" of that hub; that is, its heated condition would have burnt out the carbon of the hub and softened it. Unless the ancients had a knowledge of retempering such a hub, it could not have been used again. The reverse dies are fully as numerous as the obverse ones and no evidence of re-using these hubs has been found, although we have reverse dies showing re-cutting (Classes IX and X), and obverse dies with alterations (Cf. Nos. 1-4 and 151). We can hardly escape the conclusion, in the light of these facts, that the "hub" which has been postulated was used simply to get around the difficulty of cutting the reverse die directly in relief.

If we have reached a conviction that hubs were used at Metapontum, it does not follow that this method was used for the entire incuse coinage of South Italy. Where the reverse is very deep, the same reasons in favor of hubs found for Metapontine coins apply, but the shallow incuse coins of Poseidonia and Caulonia give one pause, and make a more careful and detailed examination of them advisable before forming an opinion. The engraved details for the coins of both of these cities, such as the trident and drapery for Poseidonia and the horns of the stag for Caulonia, as well as the inscriptions, could have been added to the die whether it had been prepared from a hub or cut directly. The herring-bone rim could also have been cut either way—a circumstance which is not true of the reverse awns of the Metapontine dies. Certain of the Poseidonia pieces have very shallow incuses and the design is limited to two planes, the second of which is only slightly separated from the other. These would not present the difficulties of modelling which the barley ear provides at Metapontum or the bull at Sybaris. In favor of the hubbing theory, however, certain of the dies which do not have such simple treatment of the design (Pl. 23, G, H, I) must be cited. Here there is cause for believing that the bungling nature of the modelling could have been due to nothing else than an attempt to cut the die directly and the contrast of this crudity with more usual finish of the other dies supports the position that hubs were customary.

The first coin illustrated on Pl. xxiii—the beautiful stater in the collection of M. Vlasto— shows the procedure at Tarentum, where but few of the incusi were struck. Note on the reverse, that the lines of the breast, the strings of the lyre, and the locks of the hair are in relief on the coin, and were therefore cut intaglio on the die. Had the die been cut direct, these elements would have had to be kept in mind from the very beginning, and the whole planned accordingly. In the stater of Sybaris with the locust (B), note the wealth of linear detail—it is hard to conceive that these lines were cut other than intaglio on the die after it came from the hub. In the PAA piece (D), note that the reverse rim must have been done similarly—i.e., after the die had come from the hub with a simple raised rim, this attempt to reproduce a cable border was made by countersinking the dots and by engraving the tiny lines between them; both the dots and the lines are in relief on the coin. In the piece from Poseidonia (F), the inscription, the trident, the details of the drapery, the features and the lines of the torso are all in relief. Note that the drapery passes behind the body, just as on the obverse—on many of the reverses of Poseidonia, it passes in front of the figure. In the stater of Croton shown, from the Hunterian collection, note that the reverse decorations of an octopus and a dolphin have no relation to the crab of the obverse.

Referring to Plate xii, it will be seen that Class VIII of the incuse ears consists entirely of what have been called "imitations". There seems to have been an attempt with at least three of these reverse dies to cut them directly, just as has been described for the late issues of Caulonia. As a result, the barley ear is very crude and the manner of cutting the awns and the border is entirely misunderstood. The awns have been engraved in the die and therefore show in relief on the coins. The border has been formed by leaving a flat rim which has been cut across at unequal intervals giving a result that is coarse and irregular. Some of the other coins on this plate leave the impression that they may have been from official dies which had fallen into unworthy hands and had been re-worked. No single explanation serves for all of them, but the treatment of the border and the awns at once reveals the novice's hand and furnishes a basis for the conclusion that the incuse format may have been a means of keeping counterfeiters from imitating these issues. A variety which had not come to my attention until after Plate xii was finished is reproduced herewith— No. 154c.

The issue for Croton and Pandosia is another latent argument for the hub theory. Please note (Pl. xxiii, E) that the bull of the reverse is in relief on a sunken rectangular field. Had it not been for the fixed idea of the die-cutter that there must be an incuse element to force the metal into the die—that is, had he not been unconscious that this result would have been accomplished with equal effectiveness by cutting the design in the surface plane of the die, rather than in the inta- glio reserve—the piece would have differed not at all from the usual double-relief issues which must have followed it very closely.

The difficulties of working with the incuse pieces of Metapontum may have been one reason for their apparent neglect. Aside from double

striking and poor preservation there are handicaps due to poor casts or worse photographs. In addition there is the question

of altered dies

to make further complications. One rather more than usually involved case occurs at the very beginning. In number I, the obverse

die shows

signs of a break above the apex of the ear and just inside the border. To eliminate these, the border was re-cut and fortunately

there are

traces of the older border which are still to be discerned. These remedies, however, did not prove sufficient, for in a third

state we have

the ear apparently cut deeper in the die and the field on either side, including the section occupied by the awns, planed

down and the awns

re-cut. Previous to this planing down the inscription had been preserved by deepening with tiny punch marks or drill holes

and these are to be

seen in specimen I c together with the traces of the awns at the previous angle in the field to the left. In the last change,

the inscription

has been made linear. On the reverse, pos- sibly the old one, but apparently the third used with this obverse, the inscription

has been engraved in the die and therefore shows itself raised on the coin. Changes so extensive as these were not frequent

in the incuse

coinage, or if they were, traces of them, with a few exceptions, have been obliterated. One of these exceptions is the obverse

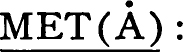

of No. 151 (Pl.

xii). Here not only traces of the earlier awns are to be seen but in the field to the left may be discerned the outline of

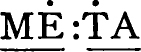

one of the divided

inscriptions.  is quite plain and strange to say, no coin with the letters in this position has as yet been

found by me.

is quite plain and strange to say, no coin with the letters in this position has as yet been

found by me.

It is the reverse dies which oftenest show alterations and many of these have to do with the border which had to withstand the tendency of the silver to spread in striking. Number 22 shows a reverse die that is broken across the inscription. Number 43 shows a reverse die from which a segment has broken in the field to the right. In Class III, however, where the raised rim becomes more regular we find sections of this rim occasionally shearing off as in number 76. When this occurs, because there is nothing to force the metal into the obverse die, the obverse border shows a blank for the space involved, which, in number 76 happens to be just below that occupied by the inscription. In Class IV, a number of the specimens show very considerable skill in mending such breaks of the reverse rim. Number 89 is a case in point and others will be found with numbers 96 and elsewhere. With casts of two or three specimens from the same die it is often possible to notice the development of the flaws and the means used to check further spreading of the fracture. Another form of break for the reverse die is shown in number 87 where the high points of the ear have flaked away leaving the coin filled in throughout the middle row of grains. This is partly due to the boldness of the relief and the size of the flan and possibly also to the incautious pairing of dies, the one imperfectly interlocking with the other. Under such conditions the grains are sometimes found worn through, leaving a hole, but because such coins are not considered desirable by numismatists, they are met with only infrequently. Another form of break which is much rarer is to be observed in number 93 where in the obverse die starting at the base of the ear, a seam has opened which extends above the inscription in the field to the left and along the cable border to a point just above the apex of the ear. Part of the border at the left has been broken away. I do not recall any die-break as extensive as this in any of the other coins which have come under my observation.

For the thick flan staters, another peculiarity is to be observed. A great many of them bear, in what is obviously their center point, a small pellet or dot. This same pellet is also to be observed in the center of the thick flan staters of Croton, with the incuse flying eagle, Cf. Pl. xxiii, L. The following is submitted as the explanation of its being there. It will be observed that in most of these cases in which a dot appears at the center, the border consists of wedge-like strokes rather coarser than the usual border and pointing toward a common center, that common center being the aforementioned dot. By some mechanical means, with this center as an application point and with a contrivance having a uniform radius, it seems to have been possible to cut the border, or possibly to re-cut it This application point, which in the die exists as a depression, when the die is used for striking, appears on the coin as a pellet. Without some agency such as the foregoing, it is hard to explain either the mechanical regularity or the coarseness of the border as compared with the fineness of workmanship which occurs on the rest of the design of the Croton staters with the eagle reverse, as well as on some of the thick flan staters of Metapontum. In the latter case it will be observed that occasionally the central point of application for the mechanical device postulated is no longer observable through surface corrosion of the piece or the breaking of the die itself at this point. Illustrations for the Metapontum pieces of the foregoing may be noticed in numbers 233, 249 and 191. The practice at Metapontum was apparently not so extensive as at Croton.

Another form of alteration which seems to have been confined almost entirely to the thick flan staters was designed to permit re-cutting of the border. The function of this reverse border was to force the metal into the die so that the rim on the obverse should come out clearly and sharply. It served as a grip on the flan and kept the flan from spreading. When, with use, the little segments into which it was divided began to wear and to lose their power of gripping, it seems to have been the practice to re-cut the border and, as we have seen, some mechanical device aided in doing this for a number of these thick flan staters. This device, however, was not used for all of them, and re-cutting was accomplished without its agency. It was possible to cut away the field of the die close to the worn rim and to bevel it down so that the transition from the old level was gradual. The greatest cutting away of the field was nearest the rim. It was simple, then, to re-cut the rim thus obtained and once more to have it gripping the flan and keeping it from slipping during the striking. In some cases the re-cut border has trespassed on the outline of the ear and very frequently the point at which the recutting has begun can be established where the end of the work overlaps the beginning. (Compare Nos. 184, 205 and 218.)

The types and symbols of the incusi do not begin to compare in importance with those of the double-relief coinage. The παράσημον of the city is the barley ear, and the conformation of the head of grain is such that there is faint cause for believing it to be wheat. The kernels of wheat are placed irregularly—those of barley are in groups of three. If one attempts to remove a kernel of barley, it will be found that there are two others joined to it and tending to leave the stem at the same time. This badge of the city is constant throughout the coinage with relatively few exceptions—on some of the bronze issues. On one type of the double-relief staters it occurs on both sides, while in one of the gold issues, we find two ears. This occurs also on the "Hannibalic half-units" identified by M. Vlasto.

For the earliest issues we have the stater, the third and the twelfth, all with the barley-ear-incuse reverse. It is possible that there were also sixths, but from the style and the manner of dividing the inscription, it is hard to believe that the pieces of this denomination with the bull's head incuse reverse came into use before the thick-flan staters and it seems probable that the twelfths with the barley grain (incuse) reverse (Pl. xxi) were contemporaneous with these sixths.

It should be noticed that the bull's head on the reverse of the sixths is not a bucranium. There are marked variations in the type as an examination of plates xxii and xxi will show. The circular frame of the die permitted the designer but scant liberty and the curves of the animal's horns are presumably a resultant of this condition. On numbers 283 and 290 the bull has short horns— either a deliberate indication of the animal's not having reached full growth or less probably a reproduction of a shorthorned variety. The downward curve of the horns is in contrast to their normal position and might lead us to think that the intention was to represent the head of an ox or bullock. The shorthorned type will bear comparison with the issues of Phocis, which, of course, are in relief. Thus, by analogy with the use of the barley ear, this type is a reference to the flocks and herds of the city as a contributory source of its wealth. We may see therein support for identification of the horned male head of the double relief series as that of Apollo Karneios rather than Zeus Ammon.

Although the barley ear is an almost constant type throughout the Metapontine coinage, the sub- sidiary symbols have exceptional variety. With the double relief issues the barley ear occupies the reverse and the obverse types change frequently. It is not my present purpose to consider these type-changes. The subsidiary symbols are not frequent on the incuse coinage, but they must be considered as a whole and, therefore, their use on the later issues must be anticipated here.

Perhaps, the first significant condition revealed by study of these symbols at Metapontum is that the explanation that answers for the earliest issues does not suffice for the later ones and that the procedure from 325 to 300 B. C. is certainly not the same as that from 425 to 400.

(a) During the period of the incuse coinage symbols are used very sparingly. Nos. 100-102, 104-105, have on the obverse a grasshopper and on the reverse (incuse), a dolphin. Others (thick flan) have as subsidiary symbols a ram's head (Nos. 221-228), a mule's head (Nos. 231-2), lizard (Nos. 209-220), murex (Nos. 229-30), and grasshopper (Nos. 258-261), while a grain of barley (or wheat) occurs on one of the thirds (Nos. 108-9). With the exception of the barley grain (and strictly, this can hardly be called an exception) all these symbols are animate.

(b) In the period of c. 335 B. C. we might take as typical the tetradrachms with the head of Leukippos20 on the

obverse. These have as subsidiary symbols the forepart of a lion and the letters A  H. The reverse

has a club as a symbol and the letters AMI. The name AMI occurs on didrachms with the same symbols21 and also with

an open-winged bird as a reverse symbol.22 The name A

H. The reverse

has a club as a symbol and the letters AMI. The name AMI occurs on didrachms with the same symbols21 and also with

an open-winged bird as a reverse symbol.22 The name A  H occurs on other didrachms

with the forepart of a Pegasus23 (although not so directly associated as with the forepart of the lion), and

elsewhere with a crescent.24 A M I also occurs on the obverse without a symbol.25

H occurs on other didrachms

with the forepart of a Pegasus23 (although not so directly associated as with the forepart of the lion), and

elsewhere with a crescent.24 A M I also occurs on the obverse without a symbol.25

(c) About 400 the procedure is much simpler —we have either the symbol or the initial letters —sometimes neither. The last condition, however, is easily explainable, for the obverse type changes would serve to distinguish the issues.

At Maroneia we find the names alone and later the names with symbols in addition. For this city the names are often complete and leave no question of two persons having names with the same initial letters. We find the same names recurring after a fairly considerable interval, the interval being indicated by weight, style or technique.

The warrant for believing these symbols to be magistrates' badges rests on a fairly firm foundation. As shown by Sir Arthur Evans,26 the Heracleian tables27 offer a close analogy, which might fairly be applied to the period to which they are attributed and therefore the procedure outlined by them is reasonably certain to have been in use for a term sufficiently long to have become established.

If we try to believe that these badges are those of magistrates appointed annually, we get into difficulties for at Maroneia we have the same name recurring two, three or even four times and at intervals. But it is obvious that these badges do serve to distinguish one issue of the coinage of a city from another. Ostensibly they have as their purpose the tracing back to a responsible individual of questions of debasing or underweight or other forms of unrighteousness in connection with their manufacture.

Viewing the question from the angle of the small city state, it is hardly reasonable to suppose that the coinage needs of the many Greek towns with mints were uniform from year to year. No mint of the modern world puts forth equal issues for each successive twelve-month—why should the requirements of the comparatively small towns of Greece be independent of the score of conditions which affect the amount of currency required for local needs ? Certainly during conflicts with neighboring rivals, the needs were greater than in times of peace. This is shown for Mende by the hoard found there in 1914. M. Babel on decided upon 423 as the year in which the hoard was probably buried,28 and working independently and viewing the evidence from another angle, my own conclusions coincided with his.29 This was the year in which the city surrendered to the Athenians and the hoard shows unmistakably a quickening of the coinage just preceding its burial. This evidence may be drawn from the circumstance that there is an increase in the number of dies or rather an increase in the number of dies which are muled one with the other, thus showing their contemporaneity. These dies are distinguished by exergual-symbols which recur on differing dies and which, therefore, may not be identified as artists' symbols or die-distinctions. Insistence here is merely upon the point that the coinage needs of Mende were greater during the period of its conflict with Athens than at a normal period and that the coinage shows this. It is now generally accepted as proven that the occasional gold issues of cities not customarily striking gold coins are attributable to a time of war—the best illustrations being the gold issues of Tarentum at the time of the coming of Alexander of Molossos and the gold issues for Athens. Unquestionably the silver issues must have felt some of this stimulus— and the more so in cities which never put forth gold issues.

In contrast, for a small city state during a long stretch of peaceful years, there must have been many conditions which would have affected the number of coins minted. In agricultural districts, the failure of crops would automatically have cut down the expenditures of its citizens and reduced the need for media of exchange. Other modifications would vary with each of the cities.

Turning to the economic aspect of the mint itself, very few of these towns had mines to provide the metal they needed for their coins. Whence did it come and how was the purchase of the metal arranged? When brought from a distance it was subject to capture by enemies, to loss in transit or to any of the many chances which one's imagination can supply. Taking such conditions into consideration, are we not compelled to give to the monetary magistrate a higher place than has hitherto been assigned him? His was a position of responsibility. He was trusted to keep the metal unadulterated—his probity was subjected to many other tests. He must have received some remuneration and this coupled with the responsibility must have made the office a desirable one. For such cities as Corinth, where the badge of the city, Pegasus, remained unchanged, and where the symbol for the issue appears beside the Athena head of the reverse, there would have been not the slightest difficulty in handing on the Pegasus die from one "magistrate" to the next. In certain of the mints there seems to be a reference through the symbols to some local occurrence rather than to a personal badge. This, however, offers but a slight difficulty if we realize that the person responsible for such an issue would presumably be well known, and therefore, need no identification on the coin itself.

Would not most of our difficulties be eliminated, if we could see in these symbols, the identification for a particular issue, thereby admitting that the symbol might be a badge or a reference to the agency responsible for it, whether that agent were an individual, whether that agency had some connection with a religious festival or a more direct relation to the temple of a local deity, or whether there were some intention of investing the symbol with significance of a purely civic or local nature, such as a victory?

But some will say, "Wherein then lies the difference between all this and the magistrate-symbol idea?" The difference lies in the application, but it is much greater than it seems. The advantage of the theory is that it gets away from the time element—from our modern way of thinking of a uniform number of coins struck for each year or that the "magistrate" was appointed for a set period. Our theory admits of there having been periods in the smaller cities during which no coins at all were struck. It also considers that during a season of stress many times the normal requirements must have been issued and by associating an increase in the coinage with known crises in the history of the city concerned, we are given a basis for dating which may prove very valuable. It has also a very direct bearing on the employment of artists for the die-cutting and makes plausible the recurrence of their signatures in more than one of the cities of Magna Graecia.

To test the theory, permit me first to apply it to Metapontum's issues. Mention has been made of the di-staters with the head of Leukippos. These form the only issue of this denomination at Metapontum and as one of the two issues of gold coins also has for its type the head of Leukippos,30 there is no reason for questioning the assignment to the period of Alexander of Epirus, if we accept the customary explanation regarding such gold issues. Just as might be expected, we find an increase in the output of staters also at this time and this is established by the occurrence of the same initials as appear on the di-staters. We find more than twenty-two dies with the lion's head for symbol with A M I and club on reverse, and sixteen dies for this type with the seated dog. We also find staters of this type with other symbols and with varying combinations of symbols and initials. We find the thunderbolt which occurs on the coinage of Alexander of Epirus and which we are accustomed to accept as his signet, associated with A M I, a name which also oc- curs without the Alexander reference. We might read from this "struck by A M I, the agent of Alexander."

The magnitude of these respective issues is indicated by the number of dies, but instead of an issue which extended over an interval equal to the collective life of the dies, it is much more logical to believe the issue to have been struck within a comparatively short period.

Earlier in the coinage of Metapontum (c. 400), we find a beautiful head of Kore bearing the first three letters of the name of Aristoxenos at the base of the neck, a position favored by this artist who signs two other dies in a similar position.31 This die, easily identified as a single die by a slight defect which gradually enlarges, is found coupled with seven reverse dies, two of which bear symbols and the others of which show slight differences in the position of the inscription or of the accompanying leaf. None of these reverse dies are found coupled with any other obverse. It seems only reasonable to believe that these reverses were used for successive issues, which were presumably frequent and which must have been comparatively small in size to permit the obverse die to outlive all seven reverse dies.

One further illustration before passing to the incuse issues which most directly concern us here. Shortly after the adoption of the double- relief style for this city, we find a series of coins with the horned head of Apollo Karneios (7 dies plus two imitations).32 These dies bear neither symbols nor initials. The reverse dies differ very slightly in the arrangement of the awns, of the leaf or of the ear. Is it not reasonable to see here an issue which for some reason sought to honor Apollo Karneios—an issue of a size necessitating the number of dies indicated? The issue may have been for a single year or may have extended over a longer time.

For the incuse pieces, the grasshopper-dolphin issue illustrated on Plate viii is typical. We have the grasshopper on the obverse coupled (1) with a reverse which is blank, Nos. 101 and 103; (2) with a dolphin in outline—incised in the die and, therefore, in relief on the coin; (3) and with the dolphin incuse—two dies. If the grasshopper is a magistrate's badge,33 what shall we say of the dolphin? Lenormant's belief that the insect was introduced with a propitiatory significance makes no allowance for the dolphin—there may have been a plague of locusts but could there have been a plague of dolphins ?33

Going back to the theory with which we started, however, there is every reason to believe that whatever its significance on these seven dies, the grasshopper is placed there to distinguish the issue. The die-combinations connote this and com- pared with this circumstance for our present purposes, the significance of the symbol is secondary. In a similar way we may consider the lizard, which appears later on the thick-flan issues. Have we not the well-known statue of Apollo Sauroktonos? Similarly the ram's head symbol might be a further reference to Apollo Karneios, but again the significance is less important for our purpose than the probability that in each case we have a single issue.

It should be noted that the grasshopper is found repeatedly throughout the Metapontine coinage— there are at least four recurrences of the symbol, all readily distinguishable, and each separated from the other by an appreciable interval. This gives color to the suggestion that this may have been the arms of a family rather than of an individual. Its use as a symbol would have been sufficient to indicate the responsibility for the issue because there would have been a general knowledge as to which member of the clan had been entrusted with the striking of that issue. On one of the later staters there is a combination which seems to support such a suggestion.

We find on this piece of about 343-39 B. C., in the field of the reverse, an owl devouring a grasshopper. Now owls are nocturnal and grasshoppers are not; furthermore, there are abundant instances of the accuracy of the Greeks' observation in such matters and we can hardly believe that such a combination would occur without intention. The owl, too, occurs previously on the Metapontine issues but without the grasshopper. Have we then a record of a feud between members of the grasshopper clan and the family whose arms were the owl, possibly for the purpose of indicating their Athenian origin? It is interesting to note that the letters which appear on this issue are A Φ A and that there are at least two dies. But the use of the grasshopper as a clan symbol does not explain its occurrence elsewhere—Messana, Mende, Velia, Sybaris. Again we are forced to the conclusion that the evidence is insufficient for dogmatism and all that we can safely deduce is that the issues with this combination of symbols belong together.

It would be presumptuous for me to try to apply this principle to the other coinages on which symbols occur. No other explanation I have found, however, works so well for the Corinthian issues, with the coinage of Abdera, or with that of the other cities whose issues have been tested. In the recently published British Museum Catalogue for Cyrene, p. lxxxix-xc, a table is given for pieces bearing magistrates' names. Just as might be expected, certain of the names are found on tetradrachms alone, while others occur on two or more denominations. Would not this connote that A's commission was the striking of tetradrachms only, from a fixed appropriation or quantity of silver, while Magistrate B's task required the issue of all denominations? If some system involving seignorage was in use, B's would probably have been the more desirable appointment. The practice must have varied in the different cities and suffered modifications from century to century, so that each mint's procedure must be studied independently. Metapontum is fairly representative of a number of Greek city-states, and the method used there may be not dissimilar to those of other centers.

The incuse coinage of Metapontum has been considered as a monotonous repetition of the barley ear type, but monotonous it is not. The ingenuity with which the design is varied is impressive, and the splendid quality behind these variations is no less wonderful. The relief ranges from exceeding boldness to the greatest delicacy. The die-cutter seems to have taken advantage of every faintest possibility of the material, utilizing not only the subsidiary symbols, such as the grasshopper, but making very decorative groupings of the initial letters of the city's name as well.

In describing these issues, it is desirable to eliminate undue repetition and to decide upon a form which will leave room for no mistake. It will be noticed that the end of the barley ear sometimes tapers and sometimes is square-cut. For distinguishing these dies (such as that of No. 88), it has been found advisable to state the number of grains in each row. The outer rows of No. 88 contain six grains each, while the one in the middle has seven, and on either side of the topmost central grain there are two tiny additional grains. In describing the dies it is the outer rows which have been counted because very often the middle row is worn and it is difficult to distinguish the number of its grains. In consequence, the formula used herein is "six-grained barley ear with small additional terminal grains." Doublestriking and wear make it advisable to rely on the number of grains to the ear except where there are no other outstanding points of differentiation.

From each of the grains in the ear extend the long lines of what we call the "beard" of the grain. The units are technically known as awns and as such are referred to hereinafter. Later, with the double relief coinage, each of these awns is shown with the small barbs with which they are equipped in nature—an instance of the closeness of observation of the Greeks, of which we shall have many another illustration.

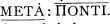

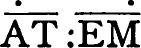

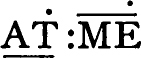

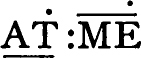

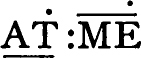

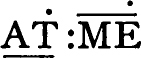

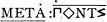

Another convention which has been used throughout applies to the inscription. Neither the British Museum Catalogue nor that

of the Berlin

Museum is entirely satisfactory or entirely free from ambiguity on this score. The scheme used is a modification of one outlined

by M. Arthur

Sambon in the Revue Numismatique for 1916.34 Again referring to No. 88, it will be seen that we have the first

four letters of the city's name and that these are divided, the two on the left being read downward, the two on the right

upward. By using a

colon to indicate the ear and placing a line above the letters to show which part of the letters (i. e., the top or the base)

is nearest the

awns ( ), there is no longer any room for doubt as to the order of the letters. When, however, as with No. 135,

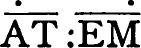

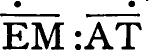

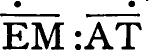

the inscription is straightforward on one side and retrograde on the other, it seems wiser not to print the latter portion

of the inscription

backwards but to make our convention meet the case by indicating the uppermost letter by a dot over that letter. The formula

for 135 thus

becomes

), there is no longer any room for doubt as to the order of the letters. When, however, as with No. 135,

the inscription is straightforward on one side and retrograde on the other, it seems wiser not to print the latter portion

of the inscription

backwards but to make our convention meet the case by indicating the uppermost letter by a dot over that letter. The formula

for 135 thus

becomes  Nor does it seem wise to repeat the archaic letters again and again. Oftentimes the

printed letter is but a poor approximation to what appears on the coins. Moreover, in the majority of cases, the letters are

readily

distinguishable on the plates which presumably would first be consulted for purposes of identification.

Nor does it seem wise to repeat the archaic letters again and again. Oftentimes the

printed letter is but a poor approximation to what appears on the coins. Moreover, in the majority of cases, the letters are

readily

distinguishable on the plates which presumably would first be consulted for purposes of identification.

It remains to indicate the broad classes into which the early coinage divides itself. For this purpose the form of border is the first criterion, although the size of the flan does enter, especially with the latest class.

CLASS I (Nos. 1-36; 37-39 imitations). For the first class the distinctive mark of difference is the pair of tiny folioles or bracts at the base of the ear of barley on the obverse. These do not occur in any other series or class. Besides this, the border is also distinctive. Usually it is described as "of coarse dots" or "grènetis". It will be seen that inside this coarse border an inner border, very much finer, begins early, (Plate II) and that this develops by steps which have a clear evolutionary trend and ultimately becomes continuous and linear. The inscription is usually confined to the first three letters of the city's name, sometimes, but not frequently, retrograde; on the obverse, with one or two exceptions they are to the left of the ear—on the reverse, to the right. These three letters also occur in a few reverse dies but in relief—that is they have been engraved in the reverse die after it was otherwise complete and therefore are in relief on the coin itself. This peculiarity is not found elsewhere in the incuse coinage until we reach the Class XI with the pieces of smallest module.

CLASS II (Nos. 40-50) is not large in numbers. In contrast with Class I, the rim is not coarse and is in the same plane or almost the same plane as the field. It is not raised as in succeeding classes. The inner linear circle which supplemented the coarser one in Class I has now as a complement, an outside circle as well, so that the border now becomes a circle of dots between two linear circles. The bracts which occur throughout Class I are absent. The inscription is uniformly to the left and of three letters only. The relief throughout is very flat, the ears are short and well-centered, and the stem long.

CLASSES III to VIII really form a single large group which has been separated for convenience of identification. There is a sharp break between this group and the two earlier groups, and no satisfactory connecting link has been found. Whether this means that there was a break in the coinage or merely a change of workmen and a consequent change of style in the output, it is impossible to say. What is more likely is that no hoard has furnished us with the issues of just this time. The classification is not strictly chronological, but neither is it purely arbitrary; the arrangement endeavors to obviate the difficulties of identifying the dies in view of the close similarity of some of them.

CLASS III (Nos. 54-84). The distinctive feature of this class is the increased module, some dies reaching 31 mm. in diameter. This is larger than any other class within the coinage. The border is similar in form to that of Class II, but is now pronouncedly raised. It should be noted also that the border for the reverse die has undergone a change and is now beautifully regular. In Class I this reverse border was coarse; in the next division it had become less crude but without having reached the form in which it appears here. (Cf. the discussion of the technical elements of this under die-making and die-breaks.) The ears are in exceptionally high relief but modelled with the greatest of delicacy. The inscriptions are uniformly to the right and either MET or META and in only one case retrograde. A comparison of numbers 58 and 79 will show that the line of progression to the next class is none too certain. It will be noticed that the reverse of the former coin has eight grains to the ear while the obverse has six.

CLASS IV (Nos. 85-99). In this class the inscription is divided, save for one exception—85a —where it is to the left. (Cf. also Class VIII for imitations.) The style is close to that of Class III in some specimens but in general the barley ears are composed of rows having six very large grains. The relief is bold and well-modelled. In this and in the succeeding class we have the introduction of the guilloche border, which is also found on some of the thick flan staters, on the coinage of Sybaris, as well as on some of the other incuse coinages of Magna Graecia. At the end of the series there are one or two dies of a reduced module (26 mm.) which have been placed here because of their divided inscription. They serve to indicate that the order within these classes was independent of our arbitrary arrangement and that these two dies probably came close to the beginning of what we call Class IX, the thick flan staters.

CLASS V (Nos. 100-111) is easily to be distinguished by the presence of the subsidiary symbols of the grasshopper on the obverse and the dolphin on the reverse, the latter in outline only, as well as intaglio. The dies vary from 28 mm. to 26 mm. in diameter and are thought by some to show the high-water mark for the incuse coinage. Border guillochée.

CLASS VI (Nos. 112-135). This class is distinguished from Class III, aside from style, chiefly by its smaller module (26 to 27.5 mm.). The inscription is in four letters but not divided (see also Class VIII for imitations). There are nineteen varieties with inscription to right, five to left. The letter A is frequently the most helpful criterion in distinguishing dies, not only in its special relation to the rest of the design but in view of its form—round or pointed top and with its cross bar downward to either right or left.

CLASS VII (Nos. 136-144). This class is easily distinguishable because of its five-letter inscription. The variations in the form of the ear show that these staters were not issued as a class. Comparison with the other issues demonstrates that they should be interpolated among the coins arranged arbitrarily (like these) on preceding plates. The coins are rather less common than most of the other varieties and show the gradual decrease in module which has been noticed in some of the preceding classes. The last two varieties really belong to the thick flan staters.

CLASS VIII (Nos. 145-154b). Imitations. These pieces because of the crudity of their style or of their lettering or of both, have been separated and placed in a class by themselves. They have been discussed at length in considering the making of dies. In general, they exhibit a lack of understanding of the methods used for the rest of the incuse coinage—a difference so great as to warrant considering them unofficial imitations. An examination of the reverse dies will bring this out very clearly, especially in the treatment of the awns and the borders.

CLASS IX (Nos. 155-208). Thick flan staters without symbols. Module approximately 24 mm. This class for convenience is sub-divided into (1) inscriptions right, (a) with three letters, (b) with four letters, and (2) inscriptions left (a) with three letters, (b) with four letters.

This is perhaps the least interesting class of the entire incuse coinage. The dies are difficult to distinguish one from another, especially when the coins are at all worn. The chief variations occur in the inscriptions, but these may have been recut in some cases. The rims of the reverses are sometimes recut—compare Nos. 176 and 191.

CLASS X (Nos. 209-232). Thick flan staters with symbols (excepting the grasshopper types of class XII). These symbols are the lizard, ram's head, mule's head, murex. The module varies from 24 to 16 mm. Some of the reverses have inscriptions engraved in the die and in relief on the coins, notably 228, 229, 230.

CLASS XI (Nos. 233-257); Small flans without symbols, ranging from 20 mm. to 16 mm. As with Class X, some of the coins have inscriptions engraved on the reverse dies (Cf. numbers 246, 247, 248).

CLASS XII (Nos. 258-261). The grasshopper types of the thick flan issues. These are separated and placed here because of their connection with the double relief issues.

There is slight reason for thinking that the date assigned by Head in Historia Numorum for the incuse coinages of Metapontum needs any changing, although there is not much positive evidence to justify making 470 the date for the last of the incuse issues. For the beginning of the coinage, we can only gauge that it must have been well before the destruction of Sybaris (510). The extensive coinage of that city warrants believing that it may have begun as early as 550 B. C. The great influence of Sybaris must have been partly responsible for the continued use of the thin incusi up to the time of Croton's victory, but for this there is only the negative evidence of hoards that the thin form did not long continue after the downfall of Sybaris. The practice of overstriking was much more common with the thick flan staters and especially with the later issues. But these, save with some of the issues from Agrigentum, offer little help in dating. M. Babelon in his Traité illustrates the Achelous piece as coming before 470 and in view of its having an obverse die identical with that of No. 91, his conclusions, based on style and lettering, are borne out. There seems small reason for doubting that the somewhat similar standing Apollo and Hercules issues in double relief also followed closely upon the thick-flan incusi. The early stater issued by Pandosia, which is so obviously modeled on these issues of Metapontum, helps to confirm this placing of them (Cf. Head's illustration and remarks).35 With the Metapontine issues in mind, it is easy to complete the obverse type, which the bad preservation of the British Museum specimen has made indefinite in the cut used by Head. The object at the lower left is clearly an altar similar to that on several dies of Metapontum.

With the exception of the Curinga and the Taranto hoards, we have no adequate account of hoards in which the incuse coins of Metapontum occur. Those listed in the introduction of Sambon's "Recherches sur les Monnaies Antiques de l'Italie" are helpful but as the varieties are not distinguished, their value is limited. A very important hoard is recorded by von Duhn 36 It was found at Cittanuova in 1879 and must have contained data which would have settled many questions regarding these South Italian issues, but aside from the portion secured for the Berlin cabinet, we know very little of its make up. Mention has already been made that so far as our present knowledge goes, these incusi are not found outside of Italy.

The Curinga hoard is one of which we have record of two-thirds of the pieces unearthed. A list of the varieties is given in a note.38 These show that the hoard must have been buried some time after the adoption of the thick-flan fabric and before the flan had been reduced to its smallest format. B. C. 490 would be a fair approximate date, judging by the issues of Metapontum alone. There are comparatively few of the issues which I consider the earliest. There are none of the grasshopper-dolphin pieces and few or none of the wide-flan and divided-inscription issues of Classes III and IV. Casts of the Metapontum pieces were prepared for me through the kindness of Dr. Orsi.

The Taranto hoard in the record made by M. Babelon provides much valuable data. It was possible to supplement this by a study of the pieces which still remained in the possession of Messrs. Spink &Son, who courteously permitted me access to this residue. The list appended gives the varieties seen.39 This hoard, again judging by Metapontum's pieces alone, would seem to have been formed at least a decade before the Curinga accumulation. There was at least one of the thick-flan staters but the crystallized condition of most of the pieces left little room for deductions concerning their circulation, although at the same time it served as a reason for believing that this thick flan stater could hardly have been an intrusion. Additions to the hoard must have ceased about the time of the beginning of the use of the thick flan format. It may have been in the process of formation during an extended period since there was a large proportion of the earlier varieties.

No. 100b, struck over a Croton stater, shares with the Poseidonia issue struck over the Metapontine type (De Luynes Coll. 524), the distinction of being one of the few overstruck incusi known to us.

It is to be hoped that some future hoard will give us more facts upon which to build. The history of Metapontum is so fragmentary that further data would be very welcome.

1a  1* Eight-grained barley ear with bracts or folioles at the base. Border narrow and light. Die-break to left of the

apex of the ear and extending to 1. to outermost awn. Double-struck—note awn to r.

1* Eight-grained barley ear with bracts or folioles at the base. Border narrow and light. Die-break to left of the

apex of the ear and extending to 1. to outermost awn. Double-struck—note awn to r.

℞ Eight-grained barley ear incuse, tapering slightly toward top.

1b Same die as 1a. The break has developed. The border is recut and is now coarse. The traces of the earlier border may be seen at the lower 1. The enlarging of the border has been at the expense of the field, and has partly eliminated the break above the inscr.

℞ Die of ia.

1c Die 1a with further re-cutting. The inscr. has been preserved in its relative position by deepening its outline with some sharp tool so that it is now a sequence of fine points. The rim and pos- sibly the ear have been deepened. The die-break at the apex has been almost, but not entirely eliminated. The awns, now at an angle of 45 degrees do not obliterate those of the earlier stage of the die, and these may be seen in the field to the left.

℞ A new die with ear having eight grains and a coarse borde—double struck.

28 mm. 7.97 The American Numismatic Society (ex Taranto H'd).

28 mm. 7.97 The American Numismatic Society (ex Taranto H'd).

1d Die in later stage than 1c. The die-break at the apex has deepened. The inscr. has been made linear, although there are traces of the stippling visible in 1c.

℞ Probably same die as 1c, altered by the addition of the inscr. which has been cut in the die and is therefore in relief on the coin.

28 mm. 7.77 Cambridge (McClean—ex Taranto H'd?); Brandis 72—8.10 (not certainly these dies).

28 mm. 7.77 Cambridge (McClean—ex Taranto H'd?); Brandis 72—8.10 (not certainly these dies).

2  Eight-grained ear. Inscription compact and with die-break to left of the M.

Eight-grained ear. Inscription compact and with die-break to left of the M.

℞ Very similar to No. 1d—possibly the same die.

29 mm. —. —Sir Arthur J. Evans; Sir Herman Weber Coll. 734, 7.47.

29 mm. —. —Sir Arthur J. Evans; Sir Herman Weber Coll. 734, 7.47.

3  Eight-grained barley ear. The dots of the border instead of being coarse are fine and regular.

Eight-grained barley ear. The dots of the border instead of being coarse are fine and regular.

℞ Eight-grained ear, the uppermost grain very small. The border narrow and finer than usual.

28 mm. 7.90 The American Numismatic Society; Naples (Fiorelli 2283); Spink &Son, ex Taranto H'd, 4

specimens, 7.58, 7.78, 7.97 and 7.97; Naville V, 427—8.15; Paris (illustr. in La Musee, 1908. p. 126); Berlin;

Curinga H'd—8.02.

28 mm. 7.90 The American Numismatic Society; Naples (Fiorelli 2283); Spink &Son, ex Taranto H'd, 4

specimens, 7.58, 7.78, 7.97 and 7.97; Naville V, 427—8.15; Paris (illustr. in La Musee, 1908. p. 126); Berlin;

Curinga H'd—8.02.

4  Broad barley ear, 14 mm. wide at base, with flattened bracts which touch the border. Relief very high and

bold. Inscr. weakly cut.

Broad barley ear, 14 mm. wide at base, with flattened bracts which touch the border. Relief very high and

bold. Inscr. weakly cut.

℞  More boldly cut than obv. Base of ear of same width as obv. Inscr. in relief.

More boldly cut than obv. Base of ear of same width as obv. Inscr. in relief.

28 mm. 8.06 Jameson (ex Taranto H'd); Bement 150—8.19; E. T. Newell, 6.69; Vienna, 7.74; Cambridge (McClean

896), 8.16; Hirsch XXX, 158— 8.20; London (B. M. C. 2), 7.84; Munich; Spink and Son, 7.90, 7.97, 7.76, 7.97, 8.10, 7.81—all

ex Taranto H'd,

and possibly from variant dies.

28 mm. 8.06 Jameson (ex Taranto H'd); Bement 150—8.19; E. T. Newell, 6.69; Vienna, 7.74; Cambridge (McClean

896), 8.16; Hirsch XXX, 158— 8.20; London (B. M. C. 2), 7.84; Munich; Spink and Son, 7.90, 7.97, 7.76, 7.97, 8.10, 7.81—all

ex Taranto H'd,

and possibly from variant dies.

5  Barley ear less broad than No. 4 which this piece may possibly precede. Die shows signs of having broken at

border.

Barley ear less broad than No. 4 which this piece may possibly precede. Die shows signs of having broken at

border.

℞ No inscription. Similar to No. 4, but the middle row of grains is narrower.

28.5 mm. —.— Paris (Taranto H'd. Cf. Rev. Num., 1912, Pl. IV, 12).

28.5 mm. —.— Paris (Taranto H'd. Cf. Rev. Num., 1912, Pl. IV, 12).

6  Eight-grained barley ear tapering toward the top and with short folioles at the base. The border very crude

but with an inner circle of dots.

Eight-grained barley ear tapering toward the top and with short folioles at the base. The border very crude

but with an inner circle of dots.

℞ Nine-grained barley ear, longer and broader than obverse. Border very crude.

29 mm. —.— Taranto H'd, 1911; The American Numismatic Society, 7.32 (ex Taranto H'd).

29 mm. —.— Taranto H'd, 1911; The American Numismatic Society, 7.32 (ex Taranto H'd).

7  The bracts are only slightly curved and do not touch border. Width of ear 8 mm.

The bracts are only slightly curved and do not touch border. Width of ear 8 mm.

℞  Similar to No. 2. Width of ear 10 mm.

Similar to No. 2. Width of ear 10 mm.

29.5 mm. 7.84. Taranto H'd, Spink &Son—three, 7.97, 7.90, 8.10; London, B. M. Cat. 4, 7.70.

29.5 mm. 7.84. Taranto H'd, Spink &Son—three, 7.97, 7.90, 8.10; London, B. M. Cat. 4, 7.70.

8  Eight-grained ear in high relief. The bracts are almost semi-circular and touch the border. Width of ear 8.8

mm.

Eight-grained ear in high relief. The bracts are almost semi-circular and touch the border. Width of ear 8.8

mm.

℞  in relief. Ear, 10 mm. wide, is broader than on obv.

in relief. Ear, 10 mm. wide, is broader than on obv.

29 mm. 8.18 Bement 152; Spink and Son, ex Taranto H'd, 2 pcs. weighing 7.97.

29 mm. 8.18 Bement 152; Spink and Son, ex Taranto H'd, 2 pcs. weighing 7.97.

9  Eight-grained barley ear. The middle row constricted to little more than a line. As in No. 12, the

workmanship is very crude. The ear is crooked. The inner border of dots is coarse.

Eight-grained barley ear. The middle row constricted to little more than a line. As in No. 12, the

workmanship is very crude. The ear is crooked. The inner border of dots is coarse.

℞ The die-workmanship is crude. The border is unlike anything heretofore.

28.5 mm. 8.10 Paris.

28.5 mm. 8.10 Paris.

10  Eight-grained ear. Inner border of dots well defined. Foliole to left curves upward at outer extremity.

Eight-grained ear. Inner border of dots well defined. Foliole to left curves upward at outer extremity.

℞ Eight-grained ear, larger than ear of obv.

27 mm. 8.00 Vienna; London, B. M. Cat. 5, 7-78; The American Numismatic Society, 7.61; Spink &Son (Taranto

H’d), two, one weighng 8.00.

27 mm. 8.00 Vienna; London, B. M. Cat. 5, 7-78; The American Numismatic Society, 7.61; Spink &Son (Taranto

H’d), two, one weighng 8.00.

11  Eight-grained ear. Thick stem.

Eight-grained ear. Thick stem.

℞ Similar to No. 10.

27 mm. 8.00 Curinga Hoard and one—possibly two others; Charles H. Imhoff; Berlin; Naples (Fiorelli 2284);

Munich; Spink &Son (Taranto H’d), two, one 7.97.

27 mm. 8.00 Curinga Hoard and one—possibly two others; Charles H. Imhoff; Berlin; Naples (Fiorelli 2284);

Munich; Spink &Son (Taranto H’d), two, one 7.97.

12  Note that E has elongated vertical stroke.

Note that E has elongated vertical stroke.

℞ Similar to No. 10.

13  Stem very short. The border of dots more pronounced. The ear broader at the centre than at the base.

Stem very short. The border of dots more pronounced. The ear broader at the centre than at the base.

℞ Similar to No. 10. Note line just within border.

27.5 mm. 8.02 Bement Sale 151; Curinga Hoard—two 8.01 and 8.00; Spink &Son (Taranto

H’d—7.78).

27.5 mm. 8.02 Bement Sale 151; Curinga Hoard—two 8.01 and 8.00; Spink &Son (Taranto

H’d—7.78).

14  Similar to No. 13, but bracts more pronounced.

Similar to No. 13, but bracts more pronounced.

℞ Similar to No. 13 but with awns at wider angle.

27.5 mm. 8.21 E. T. Newell; Curinga Hoard, 7.09; Cambridge (Corpus Christi—Lewes Coll.); Spink &Son

(Taranto H’d)—four or five, 7.81 (identification not certain), 7.97, 7.84 (two), 7.90; Naville V, 428—7.94.

27.5 mm. 8.21 E. T. Newell; Curinga Hoard, 7.09; Cambridge (Corpus Christi—Lewes Coll.); Spink &Son

(Taranto H’d)—four or five, 7.81 (identification not certain), 7.97, 7.84 (two), 7.90; Naville V, 428—7.94.

15  Compact inscription, the vertical stroke of the T extending slightly beyond the horizontal. Right bract

touches border.

Compact inscription, the vertical stroke of the T extending slightly beyond the horizontal. Right bract

touches border.

℞ Similar to Nos. 10-14.

16  Similar to No. 14 but the M and the E of the inscription are separated by an interval equal to that which

separates the E from the T.

Similar to No. 14 but the M and the E of the inscription are separated by an interval equal to that which

separates the E from the T.

℞ The ear similar to No. 11.

28 mm. 8.11 Berlin; Paris (ex Taranto Find, illus. Rev. Num. 1912, PI. IV, No. 11; ten (?) other specimens

weighing from 7.50 to 8.15, see also No. 11); W. Gedney Beatty; Arolsen; Curinga Hoard 8.00; Headlam Sale 196, 8.27; Spink

&Son (Taranto

H’d),— 7.97.

28 mm. 8.11 Berlin; Paris (ex Taranto Find, illus. Rev. Num. 1912, PI. IV, No. 11; ten (?) other specimens

weighing from 7.50 to 8.15, see also No. 11); W. Gedney Beatty; Arolsen; Curinga Hoard 8.00; Headlam Sale 196, 8.27; Spink

&Son (Taranto

H’d),— 7.97.

17  Eight-grained, square-topped ear. Short stem. Inner circle of dots well defined.

Eight-grained, square-topped ear. Short stem. Inner circle of dots well defined.

℞ Similar to No. 16.

29 mm. 8.29 (Spink &Son—ex Taranto H'd).

29 mm. 8.29 (Spink &Son—ex Taranto H'd).

℞ Ear tapering slightly toward top.

28 mm. –.— Naples (Fiorelli 2285).

28 mm. –.— Naples (Fiorelli 2285).

19  Short, compact ear of eight grains. The awns at the apex have an interval greater than heretofore.

Short, compact ear of eight grains. The awns at the apex have an interval greater than heretofore.

℞ Eight-grained ear slightly larger than that of obv.

28 mm. 7.97 Spink & Son (ex Taranto H'd); Allotte de la Fuye Sale 61, 8.20.

28 mm. 7.97 Spink & Son (ex Taranto H'd); Allotte de la Fuye Sale 61, 8.20.

20  Similar to No. 19. The bracts are unequal in length, and each touches circle of dots inside the main

border.

Similar to No. 19. The bracts are unequal in length, and each touches circle of dots inside the main

border.

℞ Closely similar to No. 19.

29.5 mm. 7.96 Locker-Lampson Coll. 17; Spink's Circular, 53358 (ex Taranto H'd), 8.29 and four others —8.10,

8.10, 8.07, 7.78; Curinga Hoard, 8.01; G. F. Marlier, Pittsburgh.

29.5 mm. 7.96 Locker-Lampson Coll. 17; Spink's Circular, 53358 (ex Taranto H'd), 8.29 and four others —8.10,

8.10, 8.07, 7.78; Curinga Hoard, 8.01; G. F. Marlier, Pittsburgh.

21  Closely similar to No. 20–possibly same die with inner border made linear. Eightgrained ear, tapering

towards top.

Closely similar to No. 20–possibly same die with inner border made linear. Eightgrained ear, tapering

towards top.

℞ Eight-grained ear, tapering towards top.

28 mm. –.— E. P. Robinson, Newport; Naville V. 64–8.19.

28 mm. –.— E. P. Robinson, Newport; Naville V. 64–8.19.

22 Similar to No. 20.

℞  In relief. Eight-grained ear.

In relief. Eight-grained ear.

27.5 mm. —.— Berlin; Pozzi 156, 7.96; Naville V, 429—7.98; Spink &Son (Taranto

H'd), 7.71, 7.97 and 7.41.

27.5 mm. —.— Berlin; Pozzi 156, 7.96; Naville V, 429—7.98; Spink &Son (Taranto

H'd), 7.71, 7.97 and 7.41.

23  Eight-grained ear. Well defined circle within border.

Eight-grained ear. Well defined circle within border.

℞  In relief. Eight-grained barley ear tapering toward apex.

In relief. Eight-grained barley ear tapering toward apex.

27.5 mm. 8.05 Curinga Hoard; Hunterian 1, 7.77; Spink &Son (Taranto H'd)—two, one weighing 8.10; Caprotti

188, 7.70.

27.5 mm. 8.05 Curinga Hoard; Hunterian 1, 7.77; Spink &Son (Taranto H'd)—two, one weighing 8.10; Caprotti

188, 7.70.

24 Similar to 18 but the ear not so broad and the inner circle linear.

℞  In relief. Eight-grained ear.

In relief. Eight-grained ear.

25  Eight-grained ear of even width. The flan is more than usually cupped. The awns have been deepened to form

a continuous line. The border shows recutting in some specimens.

Eight-grained ear of even width. The flan is more than usually cupped. The awns have been deepened to form

a continuous line. The border shows recutting in some specimens.

℞ A broken die. The break at the end of the awn farthest to the right has been repaired and the die recut for a short distance. The crack in the field to the r. has become continuous.

28.5 mm. —. ——7.99, 816. American Numismatic (2); Berlin;

Curinga H'd, 8.00.

28.5 mm. —. ——7.99, 816. American Numismatic (2); Berlin;

Curinga H'd, 8.00.

26 Die of No. 25.

℞  In relief. Otherwise similar to No. 25.

In relief. Otherwise similar to No. 25.

28 mm. —.— Spink and Son (Taranto H'd?).

28 mm. —.— Spink and Son (Taranto H'd?).

27  The awns more widely separated than heretofore. The flattened bracts do not touch the border which has an

inner linear circle, but no apparent outer circle.

The awns more widely separated than heretofore. The flattened bracts do not touch the border which has an

inner linear circle, but no apparent outer circle.

℞ Similar to Obv. in dimensions. The bracts are present at the base of the ear for the single time on the r. in the entire incuse series.

28  Seven-grained ear tapering toward top; with folioles. Coarse border similar to that of Nos. 1-5.

Seven-grained ear tapering toward top; with folioles. Coarse border similar to that of Nos. 1-5.

℞ Seven-grained ear.