Coinage of the Americas Conference at The American Numismatic Society, New York City

© The American Numismatic Society, 1988

American colonial records suggest that until the middle of the eighteenth century, peace treaties and land sale agreements between European colonists and American Indian groups were symbolized by the exchange of traditional Indian beaded belts (wampums), or animal skins.1 The awarding of medals to American Indians was therefore never a standard practice in Britain’s bid to retain possession of its American colonies or in her colonial rivalry with France. Greatly valued as official symbols of recognition by Indians, however, medals soon became inextricable from English dealings with Indians. Because of their ideological importance, the U.S. government also early adopted medal distribution as an aspect of its Indian policy. American scholars recognize the value of medals as important documents of U.S. history, yet far more research has been done on the presidential medal series than on its colonial antecedents. The standard treatments by Belden and Prucha systematically exclude these colonial medals.2

This essay focuses on the numismatic problems of an early English medal series believed to have been awarded to American Indian Chiefs by King George I. The earliest reference to this medal appears in a book by Charles Miner titled The History of Wyoming (a small town in Pennsylvania) in which he states:"Fortune was unexpectedly propitious to our search, for we found a medal bearing on one side the impress of King George the First, dated 1714 (the year he commenced his reign) on the other an Indian chief."3

The first in a series of colonial medals, this"peace medal" is not only the earliest of its kind that bears direct iconographic references (on the reverse) to the native American, it is also the most problematic. This series is probably the only bronze medal distributed before the Admiral Vernon medals of 1740, and unlike later medals we know nothing about its origins, the authority behind its issue, its authorship, date, and context of its distrbution. My paper uses archaeological, documentary and numismatic evidence to address these issues.

The corpus of George I medals comprises pieces made from bronze or copper with an undetermined alloy. A catalogue of all known examples is appended. Some examples have traces of silvering on them.4 They average about 17 g in weight, 39 mm in diameter, and 1.5 to 2.2 mm in thickness. Some had loop attachments and, where a loop has broken off, a hole was made for a suspension ring. Extremely rare in American and Canadian collections, only 19 pieces were available for analysis during my research at the ANS in summer 1985. Most of these, plus the nine pieces that were in the Bowers and Merena 26-28 March 1987 sale appear to have been recovered from burials, as they all show signs of corrosion and pitting on their surfaces.5

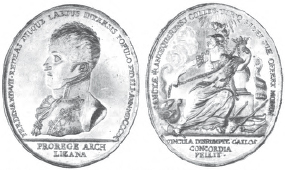

My study has identified three obverse and six reverse types. Obverse Type I has a laureate bust of George I portrayed in low relief (fig. 1). The legend GEORGE KING OF GREAT BRITAIN is spread out with the G of GEORGE starting from beneath the right shoulder. This obverse is combined with two reverses, A and B, and they are exclusive to it. Reverse A shows a figure presumed to be that of an American Indian in frontal view and leaning on a bow in his left hand while holding an arrow with his right. On top of a hill to the far left is a tree and to the right of the tree, a deer. Although similar to A, reverse B depicts the Indian in profile and in motion. This type is the smallest in size of the whole group, measuring about 37 mm in diameter, and no more than 1.3 mm thick.

Type II medals follow a similar design format as Type I, but they are larger, approximately 39 mm in diameter (fig. 2). The bust of George I on the obverse is executed in much higher relief, the transitions in facial features are smoother, and the armor and hair more detailed. The legend is close together with the G of GEORGE and N of BRITAIN starting and ending at the tips of the monarch’s shoulders. Two reverses, C and D, appear on medals of this group. In both cases the Indian is shown in the act of shooting an arrow at the stag. Reverse C has 5 branches in the tree, and a high slope to the hill, while reverse D has six branches and a low slope.

Type III closely resembles Type II on the obverse, but the bust is larger, and the relief higher (fig. 3). The shoulders are broader and the floral motif on the chest appears to be the reversal of that which appears on Type II. Two distinct reverses, E and F, are associated with this type. Similar to C and D, E and F can be differentiated by the fact that there are only four branches on the tree, and that the gradient of the slopes is higher. The only apparent difference between E and F is that the second branch at 1 o’clock appears at the node between the first and third branches in E, and on the first branch in F.

This analysis has identified two broad style groups. Type I represents a distinct group not only because of its crude obverse bust, but also because of its two reverses, A and B, which are iconographically different from those of Types II and III. A chronological sequence based on style is not possible, but this evidence suggests that the two sets of medals may be the work of two workshops or artists.

The Type I medals are unsigned, but those of Types II and III are distinguished by the artist’s initials, T.C., on the truncation of the obverse bust.

This leads to the question of attribution, which has aroused considerable speculation. None of the well known English medalists or engravers of the early eighteenth century bears the initials T.C., but the initials I.C., by contrast, are well known as those used by Johann Croker, whose medals and coins rank among the finest in English history.6 Many American numismatists have attributed the medals to Johann Croker, following Betts’s erroneous identification of the initials as I.C.7 Close examination under magnification, however, proves the initials to be T.C. American numismatists have obviously been frustrated by this apparent contradiction as the entry in the Sotheby (Toronto) 1968 sale catalogue illustrates:"George I, copper medal by John Crocker, laureate bust to right, in armour, signed TC on truncation, GEORGE KING OF GREAT BRITIAN"8

Johann Croker was the Chief Engraver of the English Royal Mint from 1705 to 1741. One of the most prominent medalists of the early eighteenth century, he executed almost all the medals of Queen Anne and George I, and also remained influential in the Royal Mint through much of the reign of George II.

It would be, then, quite reasonable to speculate that the"official" medal of George I for Indian Chiefs would have been designed by him. And such attribution seems even more convincing considering intriguing stylistic connections that exist between the bronze medals that bear the initials TC and Croker’s bust for the George I coronation medal of 1714. Yet, this evidence raises more questions than answers: Are the obverses on the bronze medals copies from an original by Croker? If so, is TC a misspelling of Croker’s initials? The busts may have been copied from an original of Croker, but the initials TC are definitely not his. Published illustrations of Croker’s medals indicate that he was consistent in placing his IC beneath the bust, rather than on the truncation of the neck.9

The authorship of Type I medals is equally speculative. Of the three types, only medals in Type I are distinguished by a six-pointed star or mullet located directly beneath the obverse bust. This seems to confirm the separate status of the Type I medals. A mullet is a common heraldic device and tells us nothing concrete about the medal. It thus poses some questions: Who owns the star, is it an artist’s personal symbol and if so, who is he? Is it a mint mark or simply a control mark to distinguish this issue from earlier or later issues?

Two names in English numismatic sources may be our only clue to the identity of the artist; George Hautsch and George Vestner who both worked at the English Royal Mint in the early eighteenth century as engravers and medalists used the mullet as personal emblems.10 Hautsch was the first to use the six-pointed star on his medals from the 1690s until his death in 1712, two years before the accession of George I. Attribution of the piece to Vestner is also doubtful on stylistic grounds, since both he and Hautsch are credited with much finer and more professionally executed medals than this mediocre design. And even when both used the star, neither pierced his star at the center as in these examples.

The search for the origins of the medals seems as problematic as finding their author or authors. Records of English colonies in North America—New York, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Maryland, and Virginia—do not mention any royal presents of an Indian Peace Medal during the reign of George I.The most comprehensive source on British medals Medallic Illustrations, describes only a medalet, listed as a"Scottish Archery Ticket" from the same period with similar iconographic features, but that identification seems tentative.11 Neither Betts nor Whiting cite primary sources to support their claims that George I issued this medal series for American Indian Chiefs at his accession to the throne.12

The paucity of written data compels us to turn to the numismatic evidence for further clues. The use of an English rather than a Latin legend, for instance, represents a significent departure from the accepted practice of the English Royal Mint. Graham Dyer, Librarian and Curator of Medals at the Royal Mint, notes that Croker also favored Latin inscriptions. He thus endorses my speculation that this feature may be"an indication that the medals are probably unofficial issues with no connection to the Royal Mint."13

That these bronze medals were private issues seems convincing on close analysis of the pieces themselves. As the medals average 1. 5 mm in thickness, it would have been difficult to strike up such high relief busts using any simple minting devices available during the early 1720s. Even with the more advanced screw press, multiple blows may have had to be used since most of the medals (particularly Types II and III) reveal signs of modeling, unevenness, and in one case cracking, on their surfaces. It appears that the pieces were struck in a screw presss without benefit of a collar. Some letters of the legend have indentations (fish-tailing) beneath the lower serifs which is the sign of the outward flow of displaced metal as the flan comes under the pressure of the dies.

Although significant, the fact that a screw press was used for the operation does not locate the manufacturing site of the pieces. Screw presses were widely used in Britain during the early eighteenth century. In London, Bristol and Birmingham, they were used for the private manufacture of buttons, toys, and allegedly, for counterfeiting coins.14 By contrast, we have no definite record of a screw press in any of the American Colonies. Massachusetts apparently owned a mechanical device that was used for the minting of its own coins about 1652. However, by 1684 the operation of the Massachusetts mint had been halted by the Crown. A decade later, Massachusetts officials appealed for a lift of the royal ban, an indication that the device was probably still operational.15

Comparison of these bronze medals with some contemporary American Colonial coins and medals, including the Pine Tree shilling of Massachusetts (1652-1684), the Rosa Americana two pence (1723), the Higley three pence (1737) and the Admiral Vernon medals (1739-41), however, reveals no stylistic connections. Official medals of the Royal Mint either before or during George I’s reign also exhibit no affinities. The letter punches used for the legends on these bronze medals are significantly different from the official British and American coins or medals. For example, not only do we find a characteristic E punch on Types II and III, but also the G punches of these types have peculiar humps on their horizontal bars. The numismatic evidence thus suggests an origin other than an American colony for these two issues. If they originated in Great Britain, they were probably produced in a private mint.

Private mint records are in general not readily available and the lack of published contemporary sources from Birmingham, for instance, makes a full reconstruction of this medal’s history difficult. However, a letter from James Logan, Secretary of the Province of Pennsylvania, to John Askew of London, dated 26 June 1726, may hold the key to unravelling the history of these bronze medals,"... I shall observe here that being out of medals it will be necessary to bespeak of Jos. Harmer of Birmingham 4 or 5 gross of the same I had of him at 36 sh. p. Gr. or perhaps Samuel Wilson in Crooked Lane will supply them at the same price but they must be of the best sort with an impression on both sides...."16

The size of the George I medal is almost equivalent to the English crown, a silver coin. Since the crown was worth five shillings, no more than four silver medals could have been obtained for each English pound. If Logan paid as little as 36 shillings for each gross (144 pieces), then his medals could only have been made of an inferior metal such as copper, which was far less expensive than silver, but more difficult to work.17 It can also be inferred from Logan’s letter that his medals may have been produced in more than one workshop, located in Birmingham and London.18 This point is particularly significant given the marked stylistic differences that exist between medals of Type I and those of Types II and III. However, the consistencies in the iconography of their reverses suggest some historical link between the pieces, possibly the same patron for all the types.

Questions regarding the authority behind the medals, when and why they were issued, can be answered by examining their specific historical context. Even though we do not have absolute dates for these medals, it is safe to assume that those that bear the effigy of George I were issued during his reign. Later issues are designated by the name George II in the legend. Thus the issue and distribution of the bronze medals seems to have begun sometime during the reign of George I and continued through much of that of George II.

The archaeological finds have mostly come from western and central Pennsylvania and western New York. Outside of this nucleus, the distribution of the medals is sporadic.19 This geographical area roughly coincides with the lands occupied by the Iroquois and Tuscarora Indians in the eighteenth century.

The American historian Herbert Osgood observed that"the wars of the seventeenth century were sporadic and mainly between European settlers and Indians. The wars of the eighteenth century in contrast were intercolonial, that is, between the British and the French. The Indians were only drawn into these wars because of alliances they had with the individual colonies."20 The crucial role played by the Iroquois and Tuscarora Indians in this respect emerges in New York City and Pennsylvania colonial records.21 By the end of the seventeenth century autonomous Iroquois groups—Seneca, Cayuga, Oneida, Onondaga and Maquase—had formed a federation known as the"Five Nations." They were later joined by the Tuscarora bringing their number to six. For many years they were considered the most powerful Indian alliance in the eastern United States, and the"Six Nations" were most valuable military allies to European colonists in North America.

Logan asserted that military alliances with these Indian nations provided the buffer and their"only security against the French in case of a rupture."22 Perhaps of equal value was the ability of the Indian communities to mobilize large numbers of warriors on short notice to defend allied colonies. The geographical and political importance of the Six Nations would thus explain why the English colonies made consistent efforts to protect and reaffirm their old treaties with the tribal chiefs.

From 1693 through 1735, however, the French made significant inroads into these alliances by offering presents to various Indian chiefs from the king of France. Fears of French attempts to lure Indians of the Six Nations were echoed in a letter of 11 June 1715 from Capt. John Riggs to Capt. Nicholson which was later transmitted to Secretary William Popple."Last week an express came down from our frontiers, that the Govr. of Canada is very busy, tempting our 5 nations to come over to them, there being great presents sent them from the King of France..."23 At least three silver medals dated to 1693, 1706 and 1710 were included in the presents to Indian chiefs.24 Many more were distributed on subsequent occasions.25

Comparable presents were not forthcoming from the British despite persistent requests from the colonial authorities to the Home Government. The desperation of the colonists was quite evident in several letters sent from New York City and Pennsylvania to the Lords of Trade in Britain. These letters repeatedly emphasized the need to counter growing French influence with royal presents to the Indians.26 New York City Governor Hunter wrote on 29 September 1715,"I must also intreat your lordships to intercede with his majesty that the Ordinary presents to the Indians upon the accession of the several Princes to the throne may be speedily transmitted. They are wanted and will be of great service at this time...."27

Although the precise nature of the royal presents was never revealed, it is on record that both King Charles II and Queen Anne distributed medals to some Indian chiefs at their accession. George I did not follow this precedent. Indeed, throughout the reign of George I and the greater part of his successor’s, no official English medals were awarded to Indians.

At the conference between Pensylvania officials and representatives of the Six Nations at Albany, 7 September 1721, Governor William Keith offered one gold medal (probably an example of George I’s coronation medal) and other presents to Indian chiefs.28 It seems that between 1714 and 1752, belts and gorgets were used extensively as symbols of alliance with Britain rather than medals.29 The only official British medal on record that was distributed to Indian chiefs was a silver medal of George II which was awarded by Governor Sir Denvers Osborne of New York to Iroquois chiefs who attended a conference at Albany in 1752.30 That the 36 year period between 1714 and 1750 represented a period of great intercolonial conflict would seem to be sufficient justification for a private medal. Thus it is not surprising that in 1757,1764, and 1766, the Quakers of Pennsylvania commissioned a series of private medals for distribution to Indian chiefs.

The historical significance of the bronze medals under study, however, lies not so much in the interaction between the Iroquois and the European colonies as a whole, but rather in the precise role played by James Logan.

Mr. Logan was a well-known scholar and Pennsylvania statesman. He had come to the colony in the company of William Penn in 1699 at the age of 25. When Penn returned to England in 1701, Logan became Chief of the Proprietary Representatives of the Penns. From 1701 on, he was agent for all land sales, a position held until 1732 when William Penn’s son Thomas arrived in Pennsylvania. Even though Logan is said to have relinquished all his public offices, including that of Secretary of the Province, in 1714 at the accession of George I, he remained liason for Indian relations for at least two more decades and also served a term as mayor of Philadelphia in 1723.31

Of all these diverse roles, Logan’s involvement in the fur trade of Pennsylvania offers the most insight into the meaning and significance of the medals.32 After surviving a political filibuster in 1705, Logan returned from England"armed with documents" to transact business for the proprietary on a scale hitherto unheard of.

But in 1708, management of the province of Pennsylvania passed from William Penn to a trusteeship representing Penn’s creditors. Logan’s political influence took a downward turn. He left public office in 1714 for private business, specializing in the fur trade. In partnership with London merchant John Askew, he bought a stock of goods to run a wholesale business suited for the Indian trade.33 By 1720 Logan owned one of the largest wholesale establishments on the east coast. He maintained two warehouses in Philadelphia, on Fishbome’s Wharf and on Second Street, from which he supplied smaller traders with sundry foreign goods imported through Askew.34 The most prominent and probably richest of the fur traders, Logan extended credit to both Indians and small traders. A description of a consignment of goods taken by one Henry Smith, a fur trader, that appeared in his journal, included medals intended for Indians.35 How many of these medals were already in circulation by 1726, which Indians received them, and on what occasions, may never be known. But Logan states quite explicity that"the Indian Goods must goe only to the traders to receive skin"36 and thus his motives for distributing the medals cannot be misinterperted. Further, since we have no official requests for medals in Pennsylvania records, or from any of the other English Colonies between 1714 and 1750, it seems almost certain that the medals were acquired for Logan’s own personal benefit.

In fact, the two motives were interwined. In addition to their military support role, the Six Nations were respected as important commercial partners. Because of the Indian Wars of Virginia and the Carolinas, which began in 1712 and lasted for nearly five years, Pennsylvania merchants, including Logan, made huge trade gains. With the wars over in 1717, competition increased as the fur trade in those southern regions was revived. Logan noted in a letter to Mrs. Hannah Penn"the tightening competition he was facing from Maryland and especially the price war that was being waged by New York City traders, not to mention constant French obstructions of free trade."37 In his letters to Askew, Logan emphasized that Indian trade goods must be of high quality. As he had stated in an earlier letter, the fur trade was his brainchild and only source of income, thus he would work toward maintaining his edge over other competitors. Economic necessity thus may have influenced the issue and distribution of Logan’s medals more than political expediency and, with more than 700 medals, he undoubtedly bought a lot of loyalty.38

| No. | Dies | Wt.(g) | Dia.(mm) | Source | |

| 1 | IA | 10.7 | 37 | Adams Coll., K.2. Kagin's (San Francisco), 29-30 Mar. 1985 (Western Reserve Historical Society), 999. | |

| 2 | IA | 38 | Wayte Raymond, 16 Nov. 1925 (W.W. Wilson), 925. | ||

| 3 | IA | 37 | M.A. Jamieson, Medals Awarded to North American Indian Chiefs, 1714-1922 (London, 1936), p. 5, fig. 3 | ||

| 4 | IB | 12.3 | 37.5 | Bowers and Merena, 26-28 Mar. 1987, 1138 (looped). | |

| 5 | IB | 11.4 | 37 | Bowers and Merena, 26-28 Mar. 1987, 1139 (looped). | |

| 6 | IB | 11.5 | 37 | ANS, purchased 1918 ("Presented to the great-grandfather of Dark Cloud of the Abenaki Tribe, St. Francis Reservation, Quebec") Jamieson, p. 6, fig. 4. | |

| 7 | IIA | 18.4 | 40 | Bowers and Merena, 26-28 Mar. 1987, 1131 (looped). | |

| 8 | IIC | 14.8 | 40 | ANS, gift of M.M. Greenwood | |

| 9 | IIC | 15.8 | 39.5 | ANS (looped). | |

| 10 | IID | 40 | Stacks, 29-31 Mar. 1973, 114. | ||

| 11 | IID | 40 | Jamieson, p. 4, fig. 1. | ||

| 12 | IID | 14.8 | 39 | ANS, gift of the Norweb Coll., S.H. Chapman, 9 Dec. 1920 (W. H. Hunter), 44. Jamieson, p. 5, fig. 2. | |

| 13 | IID | 39.5 | Sotheby (Toronto), 30 Oct. 1968, 105. | ||

| 14 | IID | 17.3 | 40 | Bowers and Merena, 26-28 Mar. 1987, 1135 (looped). | |

| 15 | IIa | 39 | SI | ||

| 16 | IIb | 39 | Morin (see below, note 3), fig. 7 | ||

| 17 | IIIE | 20.0 | 40 | ANS, gift of J. Coolidge Hills Coll. | |

| 18 | IIIE | 41.5 | Bowers and Ruddy, 28 July-1 Aug. 1981, 2672. | ||

| 19 | IIIE | 20.7 | 41.5 | Bowers and Merena, 26-28 Mar. 1987, 1133 (looped). | |

| 20 | IIIE | 17.5 | 40 | Adams Coll., 192. | |

| 21 | IIIE | 40.5 | SI | ||

| 22 | IIIE | 41 | Presidential, 6 Dec. 1986 (Paul Patterson), 261. | ||

| 23 | IIIF | 21.3 | 41 | ANS | |

| 24 | IIIF | 21.2 | 41 | Adams Coll., X. | |

| 25 | IIIF | 14.9 | 40.5 | Adams Coll., 193. | |

| 26 | IIIF | 41.5 | Archive Publique Canada, 1601. | ||

| 27 | IIIF | 18.3 | —c | Bowers and Merena, 26-28 Mar. 1987, 1132 (looped). | |

| 28 | IIIF | 18.4 | 40.5 | Bowers and Merena, 26-28 Mar. 1987, 1134 (looped). | |

| 29 | IIIF | 19.0 | 41 | Bowers and Merena, 26-28 Mar. 1987, 1137 (looped). | |

| 30 | IIIF | 41 | Stacks, 29-31 Mar. 1973, 113. | ||

| 31 | IIIF | 42 | SI |

| 1 |

I would like to thank John W. Adams; John J. Ford, Jr.; Cory Gillilland, National Numismatic Collection, SI; Cornelius Vermeule,

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and Norman Willis, National Medal Collection, Public Archives of Canada. I am deeply indebted to Dr. Alan M. Stahl of the ANS and Dr. Richard Doty for the numerous ways in which they guided my

research at the ANS during the summer of 1985.

|

| 2 |

Bauman L. Belden, Indian Peace Medals Issued in the United States

(New York City, 1927); Francis P. Prucha, Indian Peace Medals in American History (Madison, 1971).

|

| 3 |

Charles Miner, The History of Wyoming

(Philadelphia, 1845), p. 27.

|

| 4 |

Stacks, 29-31 Mar. 1973, 114, described as silver-plated brass. Extant examples of this medal show no date; nor do we find

three stars or an Indian wearing a feather, as Miner depicts in his line drawing. In"Medals in Wisconsin Collections," The Numismatist 1923, p. 16, there is a description of a specimen in the Wisconsin State Historical Museum with stars arranged identical

to those shown in Miner’s drawing— one on top of the tree and three above the Indian? The drawings in Victor Morin,"Les médailles

décernées aux indiens américains," Mémoires de la Société Royale du Canada

, 1915, fig. 7, and William H. Carter, Metallic Ornaments of the North American Indians (London, 1973), appear to have been based on Miner’s. The medals depicted may be classified as Types II or III. It may be that the

small stars are invisible on examined specimens because of corrosion or wear.

|

| 5 |

See the Appendix for a catalogue of the known specimens. No medals seem to have been recovered or observed in a ethnographic

context. Most of the archaeological finds are surface collections, and a few appear to be the result of illicit excavation.

|

| 6 |

Leonard Forrer, Biographical Dictionary of Medallists, 1 (London, 1904), pp. 472-79, which lists no Peace medals among 13 for the reign of George I.

|

| 7 |

C. Wyllys Betts, American Colonial History Illustrated by Contemporary Medals (1894; reprint ed. Winnipeg, 1964), p. 83, n. 165.

|

| 8 |

Sotheby (Toronto), 30 Oct. 1968, 105.

|

| 9 |

A corpus of works signed by Croker appears in Medallic Illustrations of the History of Great Britain and Ireland

, ed. Hawkins, Franks and Grueber (1904; reprint ed. London, 1977). Engravers of the Royal Mint in the eighteenth century

were allowed to lend their dies out for private use. Fears that the practice facilitated counterfeiting of currency were expressed

by Sir Isaac Newton, Master of the Mint from 1699-1727, in a proposal designed to curb the right of mint engravers to work

on private medals: Rupert A. Hall and Laura Tilling, eds., The Correspondence of Isaac Newton, 2 (Cambridge, 1977), pp. 405, 413,422, 446. The identity of the artist with the initials T.C. is open to speculation. Several

candidates may be listed: Thomas Callowhill mentioned in an Askew letter of 1704 in William Trent’s Correspondence (unpublished

MS in Historical Society of Pennsylvania); or Thomas Carter, a notorious counterfeiter who is mentioned in one of Newton’s

letters (Hall and Tilling, p. 405) are just two possibilities.

|

| 10 |

Forrer (above, n. 6), 2 (1904), pp. 441-42, and 6 (1916), pp. 252-57.

|

| 11 |

Medallic Illustrations (above, n. 9) 2, pl. CXLIX, 23, p. 485. The"Scottish Archery Ticket" has the effigy of King George II and is smaller that

the pieces in this corpus. Neither H. A. Grueber, Synopsis of the Contents of the British Museum Department of Coins and Medals (London, 1881), nor George Tancred, Historical Record of Medals and Honorary Distinctions (London, 1891), the two other major sources on British medals, list this medal at all for either George I or George II. Morin (above,

n. 4), p. 293, thinks that the first George I medal for Indians may have been in commemoration of the Peace of Utrecht signed

in 1713. He describes two varieties of George I medals, one with the legend"George King of Great Britain," and the other"Georgius

Mag. Br. Fr. Et. Hib. Rex" The latter is obviously the coronation medal, and the first may be a reference to our bronze medals.

|

| 12 |

Betts (above, n. 7), pp. 82-83; J. R. S. Whiting, Commemorative Medals. A

Medallic History of Britain from Tudor Times to the Present Day (Trowbridge and London, 1972), p. 117.

|

| 13 |

Personal communication Dyer to Quarcoopome, July 1985.

|

| 14 |

See Newton’s correspondence in Hall and Tilling (above, n. 9), letter n. 1347, pp. 413, 414 and 422.

|

| 15 |

This was implied in a copy of a Royal Proclamation of Queen Anne now in the ANS Library. It was some time between 1715 and 1717 that New York City made an appeal for a Royal Patent to mint copper coins: John R. Broadhead, ed., Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York City

, 5 (Albany, 1856), 462.

|

| 16 |

Quoted in Harrold E. Gillingham, Indian Ornaments Made by Philadelphia Silversmiths (New York City, 1936), pp. 6-7. There is no citation given for the letter and the context in which the request for the medals was made by

Logan is not explained.

|

| 17 |

Because of the difficulty of working copper, copper-based coinage of the early eigtheenth century was subcontracted to private

mints in Bristol and elsewhere in Britain by the Royal Mint. The practice continued at least until the end of the 1720s. See

Newton’s correspondence in Hall and Tilling (above, n. 9), letters 1403, 1431, and p. 433.

|

| 18 |

Crooked Lane was demolished to make way for King William Street in 1831. A detailed account of the street’s history is given

in Bryant Lillywhite,

London Coffee Houses (London, 1963), p. 669. The Lane, however, was probably better known for its blacksmiths quarter which is often praised in English

poetry. See, for instance, Middleton’s

The Witch of Edmonton

(1. 173) where the clown is asked to fetch bells:"Double bells: Crooked Lane ye shall have them straight in Crooked lane."

|

| 19 |

The note"A New Discovery Group of the First American Indian Peace Medals," Kagin’s, 29 Mar. 1985 (Western Reserve Historical

Society), pp. 1-3, also centers the distribution of this type in the mid-Atlantic region. According to Horace E. Hayden,"Account

of the Various Silver and Copper Medals Presented to the American Indians by the Sovereigns of England, France, and Spain, from 1600 to 1800," Proceedings and Collections of the Wyoming Historical Society 2, 2 (1886), pp. 217-38, two of these medals were found at Point Pleasant, VA, on the spot where a battle was fought in 1774.

The accession information on the piece in the ANS collection indicates that it came from the St. Francis Reservation. The

Canadian Public Archive specimen was probably collected from Canada. These two pieces may have been transported there by Iroquois and other Indians who were enticed by the French to cross over

to Canadian territory to be mobilized against English settlements: C. Hale Sipe, The Indian Chiefs of Pennsylvania (Butler, 1927). The nine medals in the Bowers & Merena sale of 26-28 Mar. 1987, were found in Natrona (about 20 miles west

of Pittsburgh) in about 1915.

|

| 20 | |

| 21 |

Acccording to W. Beauchamp,"Metallic Ornaments of the New York City Indians," Bulletin of the New York City State Museum 8,41 (1901), p. 379,"the southern Indians being of less account got no medals for a long time."

|

| 22 | |

| 23 |

Broadhead (above, n. 15), 4, pp. 414-15.

|

| 24 |

Henry Nocq, Médailles offertes par Louis XIV et Louis XV," Gazette Numismatique Française 11 (1907), p. 163.

|

| 25 |

Morin, (above, n. 4), pp. 279-89; R. W. McLachland,"The Canadian ‘Indian Chiefs’ Medal," AJN 29 (1894), pp. 59-60. Several medals were given to various Indian chiefs at a council held at Quebec in 1742, between the

Marquis de Beauharnois, Governor-General of New France and representatives of the Sioux and other tribes, see"Medals in Wisconsin Collections" (above, n. 4), p. 15.

|

| 26 |

Broadhead (above, n. 15), 4, 413, 456.

|

| 27 |

Broadhead (above, n. 15), 4, 436.

|

| 28 |

Broadhead (above, n. 15), 4, 677-78.

|

| 29 |

Treaties between English colonies and Indian groups published by Benjamin Franklin contain detailed descriptions of presents

given to Indians at such meetings. Colonial records indicate that until probably 1750, traditional Indian wampums (beaded

belts) constituted the primary symbols that were exchanged at the signing of peace treaties and negotiations for land sales

between Indians and English settlers. Animal skins, particularly those of the beaver and deer were also employed, see Frank

Speck, The Penn Wampum Belts, Leaflets of the American Indian Heye Foundation 4 (New York City, 1925).

|

| 30 |

E. B. O’Callaghan, Historical Magazine, Ser. 1, 9 (1865), p. 285; Gillingham (above, n. 16).

William Trent’s Journal for 10-24-59 describes another conference with Indians at Pitts,"Willi [Stanwix] sent for them, made each of the chiefs a

present of a silver medal, after drinking several healths the General took his leave of them."

|

| 31 |

Joseph Johnson,"The State of the Colonies, 1732: A Quaker Imperialist View of the British Colonies in America,"

Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 60 (1936), pp. 111-130, provides an interesting biography of James Logan, summarizing his career as politician, statesman

and scholar in Pennsylvania. See also Sipe (above, n. 19), pp. 84ff, and Albright G. Zimmerman,"The Indian Trade of Colonial

Pennsvlvania" (Ph.D. diss., University of Delaware, 1966). Kelly (above, n. 22), p. 160, says Logan was the mayor of Philadelphia

in 1723 but he does not identify his source of information, or how long Logan was in office.

|

| 32 |

Logan probably benefited from his privileged position as Chief of the proprietary representatives of the Penns and from his

personal relationship with William Penn. It is also noteworthy that for some time, part of the profits from the fur trade

went to the proprietary representative in London. A Pennsylvania statute of 1701 stated that"no persons are permitted to trade with those Indians but by license from Mr.

Penn." Protests were lodged by various individuals with Colonel Quarey, principal agent for the Pennsylvania Company against

this law, see Zimmerman (above, n. 31), pp. 2, 55, 67, 78.

|

| 33 |

John Askew apparently had business dealings with other prominent Pennsylvania merchants including Isaac Norris and Jonathan

Dickinson. He was also listed among partners of William Trent, one of the richest traders of Philadelphia, see Zimmerman (above,

n. 31), pp. 67, 79-80. In a letter to one Mr. Eagles, dated 31 October 1724, Logan explained that Askew lived in Ayloffe Street

in Goodman’s fields, but was to be met with daily at the Pennsylvania Coffee House in London.

|

| 34 |

Zimmerman (above, n. 31), pp. 86, 116.

|

| 35 |

Shippen family papers (Historical Society of Pennsylvania XXVII, 26) cited by Zimmerman (above, n. 31).

|

| 36 |

Zimmerman (above, n. 31), p. 80.

|

| 37 |

Zimmerman (above, n. 31), pp. 90-91, 93, 104; see also Osgood (above, n. 20), p. 85.

|

| 38 |

I am still working on the iconography of these medals. I have therefore decided to omit an in-depth discussion of it. It is,

however, significant that the hunting scene is given an emblematic status. The imagery not only reflects Logan’s economic

interests as a fur trader, but also may be an attempt to appeal to Indian sensibilities. According to J. C. H. King, Tbunderbird and Lightning: Indian Life in Northeastern America 1600-1900 (London, 1982), pp. Iff., the deer had a central position in the Iroquois economy of the seventeenth and eighteenth century.

|

| a |

The reverse is too corroded to permit die identification.

|

| b |

Possibly type II; pencil tracing after Miner’s line drawing of a piece that has not been seen since.

|

| c |

Oval, 40 x 37 mm.

|

Coinage of the Americas Conference at The American Numismatic Society, New York City

© The American Numismatic Society, 1988

Of the various Indian Peace Medals issued in North America under British rule, perhaps the rarest and most intriguing are the Happy While United (HWU) medals, dated 1764, 1766, and 1780, and undated. Without exception they are exceedingly rare. Most are housed in museums and are relatively unknown to today’s collectors.1

Before considering the Happy While United medals, however, some discussion is needed of the Montreal medal, a related undated type issued in 1761, some three years before the earliest dated HWU medal. Like the Happy While United medals, the Montreal medals were commissioned by Sir William Johnson, produced by D.C. Fueter, and issued to North American Indians with allegiance to the British Crown.

Robert W. McLachlan, in his article on Canadian Indians, described the Montreal medal as follows:"Obv. MONTREAL A view of fortified town, showing five church spires, with water in front of which there is an island; to the right on a fort is a flag displaying the cross of St. George; Ex. DCF in a small oval. Edge corded. Rev. Plain (for the inscription); size 45 m. [sic] This medal appears to be cast. The specimen in my collection is inscribed: ‘TKAHONWAGHSE ONON- DAGOS.’ The ‘DCF’ is no doubt the silversmith’s stamp."2

The identity of DCF was unknown when the hallmark was first mentioned in the literature by Schoolcraft in 1851.3 C. Wyllys Bett in his 1894 work on colonial medals hypothesized that the DCF on the Montreal medal meant D.C. Fecit or D.C. made it.4 Dr. William Beauchamp did not say who DCF was in 1903,5 nor did McLachlan unravel the mystery in 1905.6 Although partial attribution of both the Montreal and HWU medals was made by Frederick W. Hodge in 1907, DCF remained unidentified.7 However, in 1909, McLachlan reported the identity of DCF to be Daniel Christian Fueter, crediting John H. Buck, then curator of the Department of Metal Work in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City for the identification.8 This identification was followed by Chapman,9 Gillingham 10 and Jamieson.11

Daniel Christian Fueter was a Swiss silversmith who emigrated to New York City by way of London in 1754 and later settled in Bethlehem, PA, returning to Switzerland in 1769.12 He entered his mark at the guildhall in London on 8 December 1753. After arriving in New York City, he ran a classified ad in the New York City Gazette of 27 May 1754, which read:"Daniel Fueter, Gold and Silver-Smith. Lately arrived in the Snow Irene, Capt. Garrison from London, living back of Mr. Hendrick Van De Waters, Gun-Smith, near the Brew- House of the late Harmanus Rutgers, deceased, makes all Sorts of Gold and Silver Work, after the newest and neatest Fashion; he also gilds Silver and Metal, and refines Gold and Silver after the best Manner, and makes Essays on all sorts of Metal and Oar; all at a reasonable Rate. N. B. He buys old Gold and Silver Lace, and Gold-Smith’s Sweeps."

Fueter was an accomplished silversmith well known for the beautiful pitchers, vases and decorative items he produced. An exemplary specimen, a splendid silver basket wrought by Fueter in 1756, is illustrated in the Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts (Boston), October 1954, pp. 87-88.

While it was Fueter who designed and produced the Montreal medals, the man responsible for having them commissioned was Sir William Johnson. Johnson held a number of offices in the Colonial government which put him in a position of authority with respect to government relations with the Indian nations. In 1744 Sir William was appointed commissioner of the Six Nations by New York City Governor DeWitt Clinton and in 1746 he was made commissioner for Indian affairs. In February 1748 he became commander of all forces in defense of the New York City State frontiers. In 1755 General Brad- dock made him sole superintendent of the affairs of the Six United Nations, with the rank of Major General. As such, he was the leader of the expedition of the battle of Lake George, where he soundly defeated Baron Dieskau—a major turning point of the French and Indian War.13 Sir William also played a major role in the battle of Montreal; where the defeat of the French was instrumental in bringing an end to the war.

McLachlan, in his article on Canadian Indian medals, was the first to mention Sir Willian Johnson’s involvement with the Montreal medal. In that article, McLachlan quotes excerpts from a private diary kept by Johnson and correctly concludes that the medal was issued as a reward for those Indians who took part in the Montreal campaign.14 In Arthur Woodward’s 1933 article on the Montreal medal, he quotes liberally from the Sir William Johnson Papers giving further evidence that the medals were awarded to England’s Indian allies at Montreal and providing a wealth of information about how the Montreal medals came into existence.15

According to a letter quoted in Woodward’s article, Sir William was ordered by General Amherst in 1760 to enlist the cooperation of as many Indians as possible to join the British in defeating the French at Montreal.16 As the fight progressed, some of the Indian ranks joined the French side, but a sufficient number remained loyal to the British to effect the fall of Montreal in September of 1760. According to Woodward,"Apparently the idea of a medal to be issued to the faithful Indian allies of the Montreal expedition, as a token of appreciation of their loyal conduct, was born on the field of battle, probably within the walls of the conquered city and was fathered no doubt by the sagacious Sir William, who knew such a gesture would tend to cement tighter the bonds of good will and friendship between the Indians and the British Crown.17 Woodward concludes that Sir William made a list of the Indians who were to be honored with the medals (a list that Amherst refers to in a letter to Johnson, see below n. 21) and that Amherst took the list to New York City with the intention of having the medals made immediately.18

In February of the next year, Amherst wrote to Sir William to report on the progress of the medals. This letter contains the first authentic, contemporary description of the medals. Amherst wrote,"As an Encouragement to Such as behaved well during the last Campaign, I have, as I mentioned to You, I would, Ordered a Number of Silver Medals to be struck, representing the City of Montreal with a blank Reverse, On Each of which is to be Engraven the Name of One of those Indians, who, by wearing the same as a badge of Distinction, will, by Virtue thereof have free Egress and Regress to any of His Majesty’s Forts, Posts & Garrisons, so long as they Continue true to his Interests: they are not quite finished Yet, when they are, I shall send them to you, to make a Distribution of them."19

Fueter had been commissioned to do the work, which he completed in April 1761. The medals were not struck but were cast in an engraved mold. The cost of the Montreal medals is mentioned in a letter written to William Pitt by General Amherst on May 4, 1761."I have sent one hundred and Eighty two medals to Sr Wm Johnson, to be delivered to as many Indians as accompanyed the Army to Montreal, it will please the Indians much, and I trust will have a good Effect, the Expense is not great, the whole amounting to 74/6/4 Sterling."20

A total of 182 silver medals were produced and according to Amherst, one gold specimen was made especially for Johnson. On 17 April 1761, Amherst wrote to Johnson:"I send you by Capt. Minnett 182 Silver medals for that Number of Indians who were under your Command On Our Arrival in Montreal. Each medal has a Name inscribed on it, taken Exactly from the List which you gave me in Canada according to the Enclosed Copy.—...I Enclose One of these medals In Gold, which I beg your Acceptance of; and that you will permit me to say, no one has so good a right to it as yourself; for I am convinced those Indians that did Accompany the Army were Induced to it from the proper Care, and good Conduct you shewed towards them.—"21 This is the only mention in the literature of a gold medal for Sir William, and although noted by Woodward, it has not been acknowledged in the numismatic literature. Very possibly this unique specimen has been destroyed or is lying in some obscure place awaiting discovery.

The Montreal medals are generally thought to be cast only in silver, but the engraved Canadian Archives specimen (M1) is in pewter. Although Woodward was of the opinion that any pewter medal was probably a forgery, he apparently did not examine the actual medal. The present writers are of the opinion that it is genuine.

M1 (Betts 433). Edward Cogan, 19-21 May 1873 (Isaac F. Wood), 1169. Pewter, 45mm. Reverse engraved at top TANKALKEL, and in center in Roman letters MOHICKANS. Described as in good condition, composition as"some white hard substance and has a ring attached to it." See Sandham, no. 75 (where the inscription in the center is MOHIGRANS.22 The same medal is illustrated in Beauchamp with the correct spelling MOHIGRANS.23 The medal is also illustrated in the Canadian Numismatic Journal with the notation “presented to the Chief of the Mohawks for assistance in the British capture of Montreal."24

In discussing this specimen, Betts 25 describes the reverse as TANK ALKEL at the top; MOHICKANS in the field. Additionally, he noted that the description was taken from McLachlan’s paper where the name of the recipient is given as TANKILKEL, and that of the tribe as MOHIGIANS. Betts goes on to note that these are errors and that the name is spelled MOHIGRANS in Sandham. He notes that this particular specimen is in pewter, which has been confirmed to us by Hillel Kaslove.

Edward Cogan, 29-30 June 1876, 631. On reselling this specimen, Cogan included the proper description of the reverse engraving and noted the composition as"type metal."

McLachlan’s original article on Canadian numismatics was first published in 1881.26 In a subsequent article published in 1884,27 McLachlan noted his recent purchase of the Bushnell specimen of the Montreal medal (M2) and noted that it was his first opportunity to handle an original. In this article he noted that the proper reverse description of the medal sold in the 1876 Cogan sale was the one in Sandham.

M2 (Betts 431) S.H. & H. Chapman, 20-24 June 1882 (Bushnell), 286. Silver, 45mm."DCF Rev. Engraved at top TAKAHON NAGHOE, in center ONONDAGOS, in lower part subsequently engraved ‘Taken from an Indian Chief in American War 1761.’ Silver with Loop." Surprisingly this medal was not plated in the catalogue.

As indicated above, McLachlan purchased this medal and described it in his 1884 article.28 He described the reverse as"Reverse plain; ‘ONONDAGOS’ is engraved in capitals across the field, and the name ‘Tekahonwaghse’ in script at the top." We agree with this reading of the name as against that given earlier by Chapman. McLachlan again described this medal in an article published in 1899, where he identified the five churches portrayed on the obverse.29 Betts correctly listed and illustrated this specimen with a line drawing. It was sold to the Antiquarian and Numismatic Society by McLachlan and is plated in that Society’s journal in 1932.30

M3 (Betts 432). Ben G. Green, 13 Sept. 1912 (Morris, pt. 2), 483 (not illus). Silver. 44mm. Reverse engraved MAD OGHK/ MOHIKANS. Then S. H. Chapman, 9-10 Dec. 1920 (W.H. Hunter), 54, pi. 4 (obv. only). Then Glendinning (London), 15-19 June 1925 (W. Phillips), 844, illus. (obv. only).

M4. Sotheby (London), 10-14 May 1926 (John Murray & A.B. Murray), 557. Composition not listed, but it brought £70. We believe it is in silver. Reverse engraved ARUNTES, MOHAWKS. This medal is illustrated by a line drawing in Beauchamp.31

We are thus able to account for four of the Montreal medals which have appeared in auctions. Beauchamp illustrates, with line drawings, two additional medals with reverse inscribed CAN EIYA in script at the top and ONONDAGOS in capitals; and SON GOSE at the top in script and MOHIGRANS in capitals.32 Victor Morin in 1915 agreed that there were only six of these medals known.33 As late as 1955, in an unpublished letter sent to J. Douglas Ferguson, Morin continued to assert that only six of the Montreal medals were known. However, we note that Jamieson lists a seventh reverse, unillustrated, inscribed KOSKHAHHO.34 John Ford, Jr., owns two Montreal medals, one in silver and one in white metal. Due to his recent move, they are not available for study at the present time.

The Montreal medals and the Happy While United medals are closely related. As with the Montreal medal, it was Johnson who commissioned the HWU medals and Fueter who made them, but the two issues served somewhat different purposes. The Montreal medals were issued to those Indian chiefs who fought loyally with the British forces against the French at the battle of Montreal. The HWU medals, on the other hand, were used to attract as allies those Indians who still remained loyal to the French after the British had won the war and to reaffirm the loyalty of the Indians who had fought with the British during the war.

Woodward writes that in the spring of 1764, Johnson issued a general treaty invitation to those tribesmen who had been French allies in an effort to win their allegiance to the British. In July of the next year, a convocation of French Indians met with Johnson at Fort Niagara.35 Johnson knew that the leaders would be wearing French medals and wrote to General Thomas Gage on June 1 to ask for English medals to have ready to replace the French ones.36 Gage found that there would be insufficient time to have a special medal made since the medals used for such official confirmations were usually ordered from England. As the need for the medals was pressing, Gage proposed to use the dies that had been recently prepared for medals for some unspecified southern tribesmen.37 Woodward quotes a letter Gage wrote to Johnson on June 10,"I am afraid the Medals can’t be got ready by the Time you desire.I have been these two Months getting a Dye made for Medals to send to the Southward. I believe it’s now finished. The Reverse is not the King’s Arms but represents an Englishman and an Indian in Friendly Conversation. I suppose these would do for you as well as the old Pattern. I imagine when the Dye is once made that it can’t take much time to run the Medals. They are larger than yours [presumably the Montreal medal], & I will see what can be done for you immediately."38 Although there is no evidence that any Happy While United medals were ever issued to southern tribes, this letter from Gage certainly allows that possibility. Furthermore, in 1875 a Happy While United medal was found in a grave in Tennessee.39

Of the delivery of the medals, Woodward writes, The medals were finished and sent to Johnson on the 26th of the month. Gage wrote at that time saying: ‘Mr. Watkins, a volunteer setting out from hence to join the army under the command of Col. Bradstreet. I profit of that occasion to send you the 60 medals I mentioned in my letter of the 24th Inst, to have had struck off agreeable to your desire. The Mould was made for the Medals for the Indians in Florida [we infer from the use of the word"Mould" that the pieces were cast from the die and not struck] &c. & tho’ not quite as large again as that you sent to me I fancy it will answer well enough. I can not say much for the workmanship of them nevertheless they are finished by the best hand that could be found here’."40 In a subsequent letter to Johnson on July 15, Gage wrote,"Mr. Watkins an Ensign of the 30th carried the Medals from hence some Time ago, and should have nearly joined you by this Time."41

As best we can determine, the first reference in the literature to the Happy While United medals was by Schoolcraft in his history of Indian tribes in 1851,42 wherein he described a HWU medal housed at the Bibliothèque Impériale in Paris. Alexandre Vattemare cited the Schoolcraft reference in an 1861 publication43 which precipitated a note by William Sumner Appleton in his review of Vattemare.44 Betts, in his 1894 history of colonial medals, listed four HWU medals, all dated 1764 (Betts 509, 510, 511 and 513).45

In general, the obverses of the HWU medals show a bust of the King of England surrounded by the inscription GEORGIUS III D.G.M. BRI. FRA. ET. HIB. REX. F.D. The reverses, allowing for individual differences, are as described by Betts, "HAPPY WHILE UNITED. In exergue, 1764. In the field N/YORK and DCF counterstamped. Landscape, representing in the foreground an officer and at the right an Indian, seated on a rustic chair on the bank of a river. On the right a house on a rocky point, at the junction of the river with ocean, and three ships, under full sail, at sea. The Indian holds in his left hand a pipe. With his right hand he grasps the hand of the officer who is seated on his left. At his right a tree, at the left a mountain range. Silver. Cast. Size 46, with loop for suspension, formed of a pipe and an eagle’s wing."46

The known HWU medals bear the dates 1764, 1766, 1780, or no date. The obverse legend is the same on all the medals while the portrait differs slightly from medal to medal. The reverses, believed to depict New York City harbor, exhibit a few slight differences. Notably, the rarer large-size medals (72-75 mm) show three ships; the small-size medals show two. All are cast and chased in silver with a loop formed from the likeness of a pipe and eagle’s wing, except for one small-size specimen which is composed of two shells joined at the rim (HWU 12). The problem of striking a medal, whether 55 or 75 mm, with the pipe and eagle wing suspension undoubtedly accounts for the lack of any fully die-struck medals of this series. Of all the medals we were able to examine photographically, three do not bear the N:/YORK and DCF hallmarks.

HWU 1 (Betts 511?). ANS, purchased 1941 from Thomas A. Hendricks. Silver, cast, 54 mm.

HWU 2 (Betts 511?). Sotheby (London), 10-14 May 1926 (Col. John Murray and Major A.B. Murray), 559."2.2 inches" (55.9 mm). Regrettably only the obverse is plated and the cataloger did not indicate that it was undated. He created that impression, however, by reference to the illustration in Tancred which is undated.47 For clarification, we note that the wrong Betts number is listed. Thus any conclusions of precisely what this medal was, must at this time remain speculative.

Betts 511 is an undated small-size medal classified as a separate type by Betts because of the missing date. His description of this piece is perplexing for two reasons. First he notes that there are no ships on the reverse, but this is undoubtedly an error since the ANS specimen considered to be the Betts 511 type (HWU1) has two ships. Secondly, Betts dates 511 as 1764 but notes that the exergue is plain and refers to the description in Tancred, p. 49, of a similar undated medal. The line drawing in Tancred shows a series of lines across the exergue indicating perhaps that the date might have been removed either from the piece itself or from the die. Probably these"no date" pieces were produced for presentation in a different year.

HWU3 (Betts 510). Massachusetts Historical Society, ex. Appleton. Silver, cast, 75 mm. Strobridge, 12-14 Dec. 1872 (Furman), 101.

We believe that Betts 509 and 510 (cast, chased in silver, 75 mm in diameter) are two examples of the same type rather than two different types. Betts 509 is the piece described by Vattemare and noted by Betts to be in the Bibliothèque Nationale.48 Betts 510 is listed in AJN 7, p.90, as belonging to the Appleton Collection, now MHS. We believe Betts’s information had to have been sketchy because of his separate classification of these two specimens and because Betts 510 is the only HWU medal that he notes to be counterstamped on the reverse with N/YORK and DCF.

HWU4 (Betts 513). S.H. Chapman, 9-10 Dec. 1920 (W.H. Hunter), 71. Silver, cast and chased, 55 mm; reverse stamped in upper field with two punchmarks: N/YORK and DCF. Found in 1864 seven miles from Berlin, Ontario. Listed by Chapman as an example of Betts 510. Then Glendining, 15-19 June 1925 (W. Phillips), 842. Jamieson (above, n. 11), p. 15, 12. This medal apparently now resides in the British Museum.49 It is illustrated here from a cast in the ANS.

HWU 5 (Betts 513). National Numismatic Collection, SI. Silver, cast, 54 mm.

HWU 6 (Betts 513). ANS. Silver, cast, 55 mm (loop broken off).

HWU 7 (Betts 513). Norweb Collection, purchased as duplicate from ANS, 1967. Silver, cast, 55 mm. Illustrated from a cast in the ANS.

HWU 8 (Betts 513). Sotheby (Toronto), 30 Oct. 1968 (Reford), 108. Silver, cast, traces of gilding on obverse (suspension loop missing), 55 mm. This medal is the only 1764 that we are aware of that does not have the reverse punchmarks N:/YORK and DCF. For clarification we note that it was incorrectly listed as Betts 511, a variety with no date on the reverse.

HWU 9 (Betts not). B. Max Mehl, 2 May 1922 (James Ten Eyck), 2439. Silver, cast and chased, 87 mm. Reverse stamped N/YORK and DCF. Not illustrated and Mehl does not identify the"great Indian chief’ who owned this medal. Identified as Betts 511 which matches the obverse description but Betts notes that this is a 1764 medal in size 34 (55 mm) and that it is illustrated in Tancred (above, n. 46), p. 49, an illustration that is not dated. Mehl noted that he knew"of only one other, of slightly different variety, having been offered at auction, but of this particular variety, I can find no record of another specimen." Presumably he meant the 1764 Hunter specimen sold by Chapman (HWU 4).

HWU 10 (Betts?).B. Max Mehl, 23 June 1936 (Morse, Faelton and Todd), 1876. Silver, 87 mm. Noted by Mehl as Betts 511, reverse stamped N:/YORK and DCF, dated 1764. Described as probably the finest known specimen. Unfortunately not illustrated so we can offer no further information.

HWU 11 (Betts not). S.H. Chapman, 9-10 Dec. 1920 (H.W. Hunter), 72. Then Glendining, 15-19 June 1925 (W. Phillips), 843. Silver, cast, 72 mm. Jamieson (above, n. 11), p. 14, 11a; Morin (above, n. 33), fig. 13. Presumably now in the BM.

HWU 12 (Betts not). ANS, ex. W.W.C. Wilson. Silver, two uniface shells joined at rim, 59 mm. Raymond, 16-18 1925 (Wilson), 929.

There are two distinct varieties of the HWU medal dated 1766, both unknown to Betts. The Hunter specimen (HWU 11) of which an unmarked cast is in the ANS, is in Very Fine condition. It is cast and chased in silver and has a suspension loop. There is no hallmark and the reverse shows three ships. It was originally the property of Chief Waubuno, hereditary Wampum Keeper of the Delaware Indians at Muncy, PA. The medal and its pouch were purchased from the chief by G.M. McClurg of Toronto and later sold to the Oronhyatekha Historical Collection, then to the Ontario Museum and later acquired by Hunter. It was then purchased from Hunter by W. Phillips of Hampstead, England, and sold by Glendining in June of 1925. Its present whereabouts are unknown unless it is in the British Museum, having been acquired along with the 1764 piece in the 1925 Phillip’s sale.

The other known 1766 specimen (HWU 12) differs markedly in construction from the other HWU medals in that it consists of two shells joined at the rim topped by a suspension loop. The medal is 59 mm in diameter, weighs 67.72 g and is in Very Fine condition. There is no hallmark and the reverse depicts two ships. The medal was found near Niagara Falls, NY, by Ezkiel Jewett, a post trader at Fort Niagara in 1840 and eventually acquired by W.W.C. Wilson of Toronto from whom it was acquired by the ANS in Wayte Raymond’s 1925 sale. A photograph of the medal as it appeared on a 1913 postcard along with a letter giving the medal’s pedigree are in the ANS collection.

We are not aware of any written record attesting the issuance of 1766 HWU medals. Neither are we aware of any references in the literature prior to 1920 when the first one to surface was sold at auction. However Betts, citing Parkman’s"History of the Conspiracy of Pontiac," chap. 31, notes that Pontiac made peace with the English in the summer of 1765 and was given numerous gifts by Sir William Johnson at Oswego, NY, on 23 July 1766.50 Although Betts felt that the gifts included the so-called Lion and Wolf medal (Betts 535), we are of the opinion that the 1766 HWU medals may also have been issued at this time.

The latest of the HWU medal types is that known as the Virginia medal, dated 1780 (Betts 570). The obverse of this medal depicts the Great Seal of Virginia (first designed in the late 1770s) and the reverse a reproduction of the reverse of the Happy While United medals of 1764-66, with a date of 1780. The Virginia medals measure 75 mm in diameter and have a pipe and eagle’s wing suspension loop. The four known specimens of this medal are all in more-or- less Mint State condition and it seems unlikely that they were ever awarded officially or even worn.

HWU 13 (Betts 570). Described by Betts as being in the collection of W.S. Appleton, which was willed to the Massachusetts Historical Society. 75 mm.

HWU 14 (Betts 570). Raymond, 27 Oct. 1933 (Senter), 42. Copper.

HWU 15 (Betts 570). BM, since at least 1870. Pewter, cast, 75 mm. Listed by Betts as in the BM.

HWU 16 (Betts 570). Private collection, Ohio. Brass, cast, 70 mm.

Betts cited the specimen of his Betts 570, then in the Appleton collection, as made of copper as did Appleton on two published occasions.51 It seems more likely, however, that it is brass. Appleton later willed the medal to the Massachusetts Historical Society. The present whereabouts of the medal are unknown; it has not been found at the MHS and was not listed in the catalogue of the MHS sale scheduled to be held by Stack’s in 1973.52 The ANS has a plaster cast of an unidentified Virginia medal which may well be the MHS specimen.

Clearly Wayte Raymond was impressed by HWU 14, as it occupied one of only two plates in the catalogue. The whereabouts of this piece are unknown. HWU 16 was only recently discovered in Ohio and has been examined by the authors.

It seems unlikely that these Virginia pieces were issued officially. From a technical standpoint, none of the HWU medals could have been fully die struck with the eagle and pipe suspension edge with the technology available to Fueter in 1760 or even 1780. Thus, although the 1780 pewter medal in the BM is extremely sharp and detailed, it could not have been struck. The brass (or copper) cast pieces (Appleton’s misplaced piece, the Senter piece and the Ohio one), are relatively crude castings. There is little doubt that these medals were not made in or around 1780. Since the Appleton piece was known from about 1850, this may well have been when they were made. Until further data on these Virginia medals are available, they must be relegated to an apochryphal position in the Indian Peace Medal series.

Certainly the views expressed herewith on this fascinating series are not the last word, but we hope that the information available here will prompt more research by contemporary scholars.

| 1 |

A study of this type could only have taken place with the cooperation of scholars from all over the Western Hemisphere. We

wish to acknowledge the help of the following people: John W. Adams; John J. Ford, Jr.; Gordon Frost; Warren Baker; Francis

D. Campbell, Jr. and Kay Brooks of the ANS library; Hillel Kaslove, Bank of Canada, Ottawa; George Kolbe; Harrington E. Manville; Charles Rand, Cory Gillilland, SI; James Welch; Mark Jones, Keeper of Medals,

BM; and Eric P. Newman.

|

| 2 |

Robert W. McLachlan, Medals Awarded to Canadian Indians (Montreal, 1899), p. 14 (also serialized in CANJ 1899, with different pagination).

|

| 3 |

Henry R. Schoolcraft, History of the Indian Tribes (Philadelphia, 1851), p. 79, p1. 20.

|

| 4 |

C. Wyllys Betts, American Colonial History Illustrated by Contemporary Medals (New York City, 1894), pp. 226-28.

|

| 5 |

William M. Beauchamp,"Metallic Ornaments of the New York City Indians,"

New York City State Museum Bulletin

305 (1903), p. 61.

|

| 6 |

Robert W. McLachlan,"The Montreal Indian Medal," AJN 40 (1905), pp. 107-9.

|

| 7 |

Frederick W. Hodge,"French

Canadian Medals," Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico 30 (1907), pp. 830-37.

|

| 8 |

Robert W. McLachlan,"The Maker of the Montreal Indian Medal," AJN 43 (1909), pp. 155-56.

|

| 9 |

S.H. Chapman, 9-10 Dec. 1920 (W.H. Hunter), 54.

|

| 10 |

Harrold E. Gillingham,"Indian and Military Medals from Colonial Times to Date," address delivered before the meeting ot the Numismatic and Antiquarian

Society, Philadelphia, 15 February 1926.

|

| 11 |

Melvill A. Jamieson, Medals Awarded to North American Indian Chiefs, 1714-1922 (London, 1936), p. 13.

|

| 12 |

McLachlan (above, n. 8), p. 155; see also Stephen G.C. Ensko, American Silversmiths and Their Marks (New York City, 1927), pp. 88, 180.

|

| 13 |

Appleton’s Cyclopedia of American Biography (New York City, 1888), s.v."Sir William Johnson," pp. 451-52.

|

| 14 |

McLachlan (above, n. 2), pp. 13-14, citing Life of Sir William Johnson, 2 (Albany, 1841), p. 435.

|

| 15 |

Arthur Woodward,"A Brief History of the Montreal Medal,"

Bulletin of the Fort Ticonderoga Museum (1933), pp. 15-29. Certainly of all papers written on the Montreal and HWU medals, Woodward’s is the most scholarly and complete.

Although written 55 years ago, it was previously neglected by numismatic scholars.

|

| 16 |

Woodward (above, n. 15), p. 17, citing the Sir William Johnson Papers, 3 (Albany, 1921), p. 272.

|

| 17 |

Woodward (above, n. 15), p. 17.

|

| 18 |

Woodward (above, n. 15), p. 17.

|

| 19 |

Woodward )above, n. 15), pp. 17, 19, citing Johnson, 3, pp. 317-18.

|

| 20 |

Woodward (above, n. 15),p. 23, citing Johnson, 3, p. 386.

|

| 21 |

Woodward (above, n. 15),pp. 22-23, citing Johnson, 3, p. 378.

|

| 22 |

Alfred Sandham, A Supplement to Coins, Tokens and Medals of the Domain of Canada

(Montreal, 1872), p. 10, 75, illus.

|

| 23 |

Beauchamp (above, n. 5), pi. 26, 284.

|

| 24 | |

| 25 |

Betts (above, n. 4), p. 194.

|

| 26 |

Robert W. McLachlan,"A Descriptive Catalogue of Coins, Tokens, and Medals Issued In or Relating to The Dominion of Canada and Newfoundland," serialized in AJN, 1880-85. Republished as a book of the same title (Montreal, 1886).

|

| 27 |

Robert W. McLachlan,"The Montreal Indian Medal," AJN 18 (1884), pp. 84-87.

|

| 28 |

McLachlan (above, n. 27), p. 85.

|

| 29 |

McLachlan (above, n. 2), pp. 13-14.

|

| 30 |

CANJ 1932, p. 132, p1. 4, 1 and 2.

|

| 31 |

Beauchamp (above, n. 5), p1. 26, 283.

|

| 32 |

Beauchamp (above, n. 5), p1.26, 281 and p1. 33, 388.

|

| 33 |

Victor Morin,"Les médailles décernées aux Indiens d’Amérique," Mémoires de la Société Royale du Canada

(1915), p. 304.

|

| 34 |

Jamieson (above, n. 11), p. 10.

|

| 35 |

Woodward (above, n. 15), p. 27.

|

| 36 |

Woodward (above, n. 15), p. 27, citing Johnson, 4, p. 437.

|

| 37 |

Woodward (above, n. 15), p. 28.

|

| 38 |

Woodward (above, n. 15), p. 28, citing Johnson, 4, p. 447.

|

| 39 |

AJN 10 (1876), p. 54.

|

| 40 |

Woodward (above, n. 15), p. 28, citing Johnson, 4, p. 453.

|

| 41 |

Woodward (above, n. 15), p. 28, citing Johnson, 4, p. 482.

|

| 42 |

Schoolcraft (above, n. 3), p. 79, pi. 20.

|

| 43 |

Alexandre Vattemare, Collection de Monnaies et Mé dailles de I’Amérique du Nord du 1652 & 1858 (Paris, 1861), p. 76.

|

| 44 |

AJN 2, (1868), p. 110.

|

| 45 |

Betts (above, n. 4), p. 226-28.

|

| 46 |

Betts (above, n. 4), p. 227.

|

| 47 |

George Tancred, Historical Record of Medals and Honorary Distinctions Conferred on the British Navy, Army, and Auxiliary Forces (London, 1891), p. 49.

|

| 48 |

Betts (above, n. 4), p. 227.

|

| 49 |

Sotheby (Toronto), 30 Oct. 1968 (Reford), 108, note describing the example in the BM illustrated in Jamieson.

|

| 50 |

Betts (above, n. 4), p. 238.

|

| 51 |

William S. Appleton in a letter in AJN 7 (1873), p. 90; see also Appleton, AJN 2 (1868), p. 110.

|

| 52 |

Stack’s, 29-31 Mar. 1973. The lots consigned by MHS were withdrawn prior to the auction.

|

Coinage of the Americas Conference at The American Numismatic Society, New York City

© The American Numismatic Society, 1988

To understand the current thinking on what we call the"Spanish medal in America," that is, the medals produced in territories under Spanish rule, we have to consider some fundamental studies from the turn of the century. We can then examine the policies behind the introduction of the earliest medal in Spanish America, whose influence extended to the medals of later periods. A consideration of the circumstances of the introduction and spread of the medal, which we intend to follow here in its general outlines, will shed light on the colonial policy as a whole.

Regarding published sources, the works of Medina on Spanish colonial medals, published between 1900 and 1919, remain fundamental;1 supplemented by Herrera’s 1882 work on Spanish proclamation medals2 and Vives’s 1916 book on medals of the House of Bourbon.3 These works all exhibit a similar point of view; they differ in that Medina focused on the American case individually, while Herrera and Vives considered it in the context of Spanish history as a whole. In more recent years, while several works have treated the development of the Academies, especially that of Mexico,4 from a variety of viewpoints, the medals themselves have only been treated in isolated works which are basically catalogues for collectors.5 In a recent study, I examined the medallic activity of the Academy of San Carlos, and placed it in the context of Spanish and American medallic activity.6

The first question to deal with must be the validity of the term Spanish in this medallic production, the extent to which it is a manifestation of Spanish intention and the role played by interests, producers, manufacturers, and recipients. To this end, we shall examine three points of reference whose influences complemented each other: the proclamation medal; the work of the mints; and the work of the academies.

The first documented medal in the new world, of which no extant specimens are known, is that of the proclamation and oath of Philip II in Lima in 1555. Medina has critically analyzed the documentation published by Herrera.7 To its difficulties of interpretation is added the uniqueness of the case, not only since, as Medina has explained, this was a medal for Lima alone, but also in that there were no analogous medals, either extant or known from documents for the next century and a half. In any event, the mention of a royal proclamation ceremony of the sort typical of Spain, including the distribution of medals with the king’s image, remains significant. The use of coins in this context on the American continent is attested indirectly for this period and explicitly for later times. We cannot therefore eliminate the possibility, if we accept the explanation of the development of American proclamations proposed by Medina, that the lack of a mint in Lima in 1555 led to the creation there of a medal to fill a role served by coins elsewhere and in Lima itself at a later date.8 In any event, we have here the earliest evidence for connecting the origin of the Spanish-American medal with the ceremonies attendant on a royal proclamation.

Apparently, the singular form in which the Renaissance medal was adopted in Spain did not lend itself to export to the new world because of the different social and political relationships.9 The notice published by Medina of a medal of Gonzalo Pizzaro stands out as an exception.10 Only the proclamations of kings, documented from the time of Philip II (that is, the official government activities), would serve as the occasion for the creation of coins or medals to disseminate the image of a new king.11 The single case documented for the Hapsburg Dynasty does not allow us to do more than speculate about this activity on the basis of what happened in the eighteenth century. This is confirmed by the fact that from the appearance of the earliest extant specimens of 1701, the proclamation medal remained for many years in Spanish-America, and, even after the introduction of other genres, continued to be the dominant form.

The geographical distribution of the cities in which medals were minted for the six proclamations up to 1808 can serve as an index of the spread of the Spanish medal on the American continent. From the data assembled by Herrera, Medina and Grove, we can discern a progressive extension and intensification of the production of the medals. Mexico served as an initial focal point and remained the area of greatest production. From there, production extended in two directions—to the Caribbean Islands and to the south—a distribution still apparent in 1808. Though the regional configuration of proclamation medals is related to the location of mints, it corresponds more closely to clearly-defined economic regions; for example, the region of el Plata, which had no mint in this period.

However, some exceptions are apparent, with some places and issuers fluctuating radically in output, not only on a local scale as was frequent in New Spain, but occasionally as an entire region. Cuba, for example, had been previously normal in its production, but produced no medals for the proclamation of Ferdinand VII in 1808. The outpouring of medals on the island in 1834 can be seen as a reaction to the independence of the continental viceroyalties. Nevertheless, the distribution is generally representative of the lines of development in Spanish America during the eighteenth century.

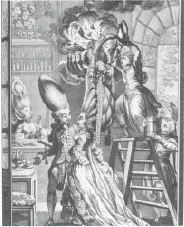

The earliest known examples are for the proclamation of Philip V in 1701 (fig. 1), which were limited to the two cities of New Spain, Mexico City and Veracruz, issued no doubt by municipal authorities.12 Both are of cast silver and correspond, as Medina pointed out,13 to the prototype of the medal for the proclamation of Philip V in Cadiz (fig. 2), dated 1700.14 The 1701 issues have the same obverse (except for the date) and retain the titulature of the Cadiz piece with no mention of the New World; the Mexico City piece has on the reverse the inscription IMPERATOR INDIARVM together with the arms of the city. These characteristics, together with the mediocre quality of these pieces, leads to the inference that they were the product of silversmiths’ workshops. This conclusion is supported by the documented production of proclamation medals in Spain by silversmiths trained as artisans rather than in the fine arts.15 In America, on the other hand, such documentation is common as in the case of Gonzalo Pizzaro mentioned above.16 From such examples, it can be affirmed that even if in its concept the medal was introduced as a royal proclamation, in practice its development was bound up with and influenced by the artisanal world, specifically silversmiths.

This can be seen, above all, in the clear connection between peninsular and American workshops, in spite of the existence of American mints and the documented use of coinage in connection with proclamation ceremonies.