Coinage of the Americas Conference at The American Numismatic Society, New York City

© The American Numismatic Society, 1985

In the summer and fall of 1862, the Confederate Treasury Department faced a whole series of crises; crises, one might note, that were to a considerable degree of the Secretary's own making. By failing to prod Congress vigorously in the matter of taxation either during the Provisional Congress or during the opening session of the First Regular Congress, Secretary Christopher G. Memminger had guaranteed the absence of fiscal revenues and permitted the Congress to place the whole burden of supporting the war on the monetary side of the Treasury. And since even Secretary Memminger was well aware that a plantation economy had only a limited lending capacity, particularly if its crops could not be sold (as was the case from 1861 on); this meant in turn that all expenses would have to be met by the use of a government currency.

But for probably the first time in history, a goverment hellbent on a printing press economy was hindered in its goals by the absence of the printing personnel and materials needed for that purpose. Henry D. Capers, Chief Clerk of the Treasury Department during the Provisional Government and Memminger's biographer, pointed out with only slight exaggeration that there was only one security engraving establishment in the whole South, consisting of a small shop manned by one engraver, his young son, and an assistant (the American Bank Note branch in New Orleans, which masqueraded during its Confederate period under the adopted firm name, Southern Bank Note Company). The reality, though, was bad enough with only three engravers and half a dozen lithographers, together with the typeset capacity available to the firm of Evans & Cogswell in Charleston.

These ludicrously inadequate resources, not all of which were available to the government, obviously had to be augmented and were—with imported talent, materials and the inducement of various non-printing oriented businessmen to take in hand the task of organizing and operating securities printing firms. Unfortunately, numerous blunders were made in this ad hoc approach to the problem, fundamentally attributable to Secretary Memminger's undisguised laissez-faire beliefs and his hard money view that the treasury notes could and would be dispensed with after the war as a means of public finance. As shall be shortly seen, others more perspicacious than he, watching the growing tidal wave of "Memminger's Gigantic Skunk Cabbage" otherwise known as the Confederate currency, had come to a different view without ever being able to convince the Secretary of the error of his ways. The Secretary's attitude found its most pernicious expression in his refusal to regulate the activities of those who, because of the capital, materials and manpower furnished to them by the government, were little better than extensions of the Treasury. As a result, no permanent arrangements were made—contracts let printers use Confederate resources for the manufacture of rival state, bank and private currencies while less profitable Treasury orders were left unfilled.

Equally undesirable was a whole train of other evils. Without adequate supervision, printers multiplied the number of designs for each denomination, thereby promoting confusion and making the work of even the most inept counterfeiters easy. Moreover, too many high denomination notes had to be printed to meet the Treasury's needs thereby dislocating the currency. And above all, the competition which the Secretary promoted in the interest of trying to reduce the printing bills (regulating the production of unnecessary plates would have been more to the point of getting rid of bill padding) only resulted in cut-throat maneuvers in which the stealing of one another's workmen, arson, interception of rivals' supplies and elaborate intrigues, not excluding trumped-up treason charges, wasted the time and energies of all concerned, while hundreds of thousands of soldiers deserted the Confederate Army for the lack of food, clothing, arms, shelter and pay, because of an empty Treasury.

These cancers in the Confederate financial program (if it can be honored with such a name), reached acute form in the summer and fall of 1862 because of two factors which might have been reasonably anticipated. First, there was a striking need to reduce the currency to manageable size by a forced funding program. This meant that the printers would have to print a large quantity of bonds which would divert them and their limited printing capabilities away from the currency, itself urgently needed to pay past and present bills. Then, thanks to a group now known as the Payne brothers, Yankee intruders penetrated into the South where they distributed nearly $2 million of counterfeit money, thereby causing the public to refuse to receive nearly $150 million of notes printed by the firm of Hoyer and Ludwig. Thus the government had to catch up on $50 million of arrears, clear off a minimum of $ 150 million of discredited currency plus another $ 100 million which needed funding, together with the bonds into which these were to be funded, plus produce the $40-$50 million per month needed to meet current needs. And all this new currency clearly needed to be of better quality than the earlier issues to avoid the counterfeiting panic which then engulfed the country.

It was obvious therefore that there were going to have to be radical changes in the way the Treasury produced its securitites, the designs of the currency and the relations between the printers and the Treasury. Equally, the Treasury was going to have to tackle the inhouse bottlenecks which were also a contributory factor in this vexatious equation.

Characteristically, the Secretary chose to address himself to these last first. Among the most pressing of these was the delay imposed on getting currency and bonds out—each note was autograph signed by clerks, each bond was signed by the Register and each coupon was signed by one of his clerks. The United States and the Confederacy had both faced this problem in mid-1861 when the Treasurers and Registers on both sides had been relieved of the duty of signing all notes personally. This had been carried one step further in February 1862 when the United States legal tender legislation allowed printed signatures. The Treasury, by way of precaution, printed the Treasury seal on every note not printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, which had been established with a view to getting out Government securities without the aid of banknote firms whose self-interest made them suspect in Washington.

If signing notes by hand was speedily discarded in comparatively manpower—rich Washington, continuing such practice in Richmond was sheer folly. Fortunately, the Union invasions had created quite a number of refugees and Secretary Memminger had availed himself of the work force thus unintentionally furnished him to hire a corps of women who performed these duties while male clerks were diverted to more important tasks or shipped off to the army. However, this system did not always work well as the work force was not used to keeping business hours, while sickness and "female complaints" etc., left the signing forces out of balance (notes signed by one person each from the Treasurer's or Register's division) or short by one designated partner or another. Printed signatures, which the Congress had not heretofore seen fit to authorize, were a clear necessity.

Accordingly, Secretary Memminger wrote in July 1862 to the Chief Clerk of the Treasury Note Bureau in Columbia, Joseph D. Pope, asking him to sound out the printers on the feasibility of using printed signatures. On July 31, Edward Keatinge, on behalf of the his firm, Keatinge & Ball, replied, advising the use of printed signatures with the same precautions used in Washington, that is, the application of a seal to each note, before issue, and without which the note would be invalid.1 The Secretary duly petitioned the Congress for the necessary legislation, but with the exception of the 50 cent notes authorized by the an act in April of 1863 (and later the bond coupons), such permission was never forthcoming. Thus the Treasury would have to struggle on until the end of the war with clerks signing $1 and $2 bills worth perhaps 2-5 cents in coin.

The next question was what to do about the relations between the Treasury and its recalcitrant contractors. Fortunately, a series of events transpired in 1862 which offered new opportunities to anyone with the wisdom and vigor to exploit them. The most important of these was the providential arrival in the South, aboard the Giraffe , of a crew of 20 Scottish lithographers whose services had been contracted for in London, on behalf of the Confederacy, by Major Benjamin Ficklin, Quartermaster General of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Ficklin, who had been in London to procure military supplies for Virginia, had undertaken the additional commission of hiring printers and did so. The printers had been contracted for on two very specific terms; first they were to be paid £4 a week in coin and second, they were to work exclusively for the Treasury and not for any private contractor or any person engaged in the printing business for profit. These terms were almost made to order since had the Secretary the mind to do so, he had the nucleus with which to set up a Confederate Bureau of Engraving and Printing. It would then have been a simple matter to divert the printers detailed to the contractors by the Army, cut off the subsidies, take back the equipment lent to the contractors—and the contractors would have had to surrender to any terms the Secretary might offer them. He could then keep those he needed, get rid of those who were inefficient, quarrelsome or unnecessary and make sure that all the printing work done benefitted the Treasury alone so that it would be able to meet its needs. It says something about the desperate straits in which he found himself that Memminger overcame his prejudices on the point to at least make inquiries as to its feasibility.

The reply that he got from Pope was not very encouraging, certainly not in every particular. As Pope put it in his August

18, 1862 letter:2

I do not think we will mend the matter a great deal by putting three of four contractors in one house and calling them a Government

establishment. They would quarrel still, and perhaps worse than ever. All want to be masters, and all want the profits. This

is the whole truth, and all the trouble they have been giving me had been in their efforts to outdo each other. All wish to

dictate

just as soon as you do not yield to their particular schemes...

In fact, if it was not that I feel that I would not be doing my duty to my country, I would kick them all over together and

quit. I have never been so annoyed in my life. They deliberately desire to use me to outwit each other. It is impossible for

you at a distance to see the will and won't policy of these contractors...These contractors have no idea of doing anything

that will take away from the profits. To counteract all of this, I would with great deference propose that a real Government

establishment be inaugurated (for a long time after a peace these notes will have to be used), and to this end I have suggested

that paper in large quantity be imported, and lithographic material, as well as steel-plate material and presses, and men

in sufficient quantities to put the Government beyond the control of contractors.

The Secretary, perhaps because of his confidence in the capabilities of Pope and no doubt governed by his desire to avoid a Government currency after the war (which the absence of a Government establishment would neatly impede), chose not to act on this advice, although he did promulgate various rules at Pope's suggestion, which greatly limited the scope of the printers' powers, cut off the magpie—like stealing of one another's personnel and some of their other shoddy practices.

There only remained the question of what to do about the currency. For manifestly, as the counterfeiting panic had proved, there was no way in which they could continue along the disastrous course already pursued. The currency needed to be standardized, and improved in quality and measures taken to speed up its production by cutting out as much individual plate-making as possible. Once again, Memminger turned to Pope and an extensive study was made of the whole subject. And since the views of the contractors, with the exception of Keatinge on purely technical matters, was hardly disinterested, Pope leaned heavily on the views of George Dunn, the leader of the Scottish lithographers, who was destined to become a small-time contractor in Richmond during 1863-65.

As George Dunn summarized his views, which were passed on to Secretary Memminger:3

Sir: Supplementary to the short conversation I had with you on Thursday last, in which I briefly pointed out the necessity

for adopting a different course than hitherto

pursued with the engraved issues of Confederate paper, I beg to state that, having examined the issues, in no instance is

there an original design, either in denominational ornament or vignette, to be found in one of these notes. The centralization

of bank-note engraving as a system, and the very fine style in which American paper has been gotten up in New York City, are points long since acknowledged. Machinery may be found there not more to be admired for construction than admirably

adapted for producing any kind of device requisite to fine variety and beauty to promissory notes. The engraving of the figures

and vignettes has reached a point approximating perfection; but the very limited number of first-class draughtsmen and engravers,

compared with the enormous demand for paper in America, arising out of its low denominational value, has given rise to an injudicious use of the transfer press for reproducing

engravings on both steel and copper. In this and other ways, demand has been met, and the first great element of security

for a note, viz., originality of design in the ornament as in the writing, has been lost sight of. Any artist contented with

excellence and beauty only, and satisfied to ignore invention altogether in his productions, may find all the assistance he

requires in any of the many aids to engravers published in the North; but the duplicate engraved plates being also there,

he is very much at the mercy of the men whose ideas he borrows.

Practical men in England had some difficulty in deciding how you would overcome those connected with your circulation, New York City being the producing place; they had no idea you would adopt a plan of operation which gives to the men in the North the power

to issue the originals you have been content to copy. There has been exhibited a want of prudent thought on this subject most

culpable; and as Government officials could hardly be expected to be acquainted with all the minutiae of the art, the enormous

injury inflicted on the Confederacy is fairly to be charged against those who have set up this system of imitation. Three

designs for dollar bills were shown to me last week about to be forwarded to Colonel Memminger for his approval by Mr. Keatinge.

If this gentleman did not perceive the danger in which he stood as to professional reputation, he might at least

have discovered how much he jeopardized the Confederate States circulation. Bills got up in the style of these is just imitation

"made easy." Profusely and elaborately ornamented as they were, they showed some perfect gems of art, but the condemning fact

was just as palpable as their beauty. Without one redeeming exception, every item of ornament was a specimen from an existing

engraving. If we cannot altogether defy spurious issues, we need not assist them. If we cannot, for present want of machinery

and material, come up to that degree of excellence which has been attained in the North, let us adopt a style of our own,

and for the perfections of a lengthened experience substitute originality of idea. I do not enter on the question of printing

from engraved plates transferred to stone, or from the plates themselves, or to the question of electrotypic art as used in

the Bank of England for note production. To accomplish the Government intentions, except by printing from engraved plates

transferred to stone, at least from 150 to 200 copper-plate presses would be required. This fact for the present establishes

lithography as a necessity....

Certain points made in Dunn's letter require commentary and amplification.

First, there can be very little doubt as to the lack of originality of the Confederate currency up to that time. With the exception of the Confederate leaders' portraits appearing on such notes, there was nothing new in the whole series. It was not merely that the lettering and vignettes were copied from notes already in circulation in the South, the originals being, as Dunn properly pointed out, in the North; it was no less true that whole notes or parts of them had been copied from plates available in the South, the masters of which were also in the North. For example, The first Leggett, Keatinge & Ball notes, types 23 and 324 were reengravings of the notes of the Farmers and Mechanics Bank of Savannah; the green portion of the type 21 note was taken from a plate for the Commercial Bank of Columbus, Mississippi. Likewise, as has been demonstrated in the March 1972 edition of The Numismatist,5 the Indian Princess note, the Women with urn-Eagle and Shield notes (types 35, 27, 28) were all created from plates lent by the Bank of Charleston, South Carolina. And the spoils of the American Bank Note Company branch in New Orleans yielded the plates of the Banque des Ameliorations of New Orleans, which in turn was converted for use on the Keatinge and Ball types 33 and 34 $5 bills. Still worse, much of this art work was 20 years or more behind the times, had lost its copyright protection, and was no longer to be had just at American Bank Note. Anyone so minded could become an accomplished counterfeiter with just that ease cited by Dunn.

But having diagnosed the evil, what was to be done? There was neither time nor money to import the men and material to emulate European bank note printing nor, given the southern conservatism, would public opinion have looked with favor upon so radical a departure from past practice. The solution was to keep the general appearance of American notes while doing work that was as original as possible. Obviously, there was not time to redo everything, but much of what had been done did have some distinct features and those should and could be exploited. Accordingly, notice was sent to all the engravers of the government's intention to create a uniform type note for each denomination and for those interested to submit to a committee appointed by the Secretary their proposals as to how the new notes ought to look. Therefore, Keatinge in July 1862 came to Richmond to make drawings of Confederate leaders, soldiers, buildings and so forth in order to furnish new designs for the upcoming contest. On September 6, the Committee met and after reviewing the various proposed signs forwarded a report with their recommendations to Secretary Memminger, as follows:6

Sir: In obedience to your instructions, we beg leave to report that designs for Confederate notes have been submitted to us by Colonel Duncan, Messrs. Keatinge & Ball, George Dunn, and Messrs. Paterson & Co. To save time and have the aid of some experience, we invited Messrs. William Thayer, of the Bank of Charleston; E. J. Scott, of the Commercial Bank of Columbia; and Mr. Strobel, of the Farmers' and Exchange Bank of Charleston, to meet with us and examine the designs. Assisted by them, we have made the following selections: One dollar note, with the head of Mr. Yancey, of Alabama, designed by Messrs. Keatinge & Ball, has been selected without alteration.

Two dollar note, with the head of Mr. Benjamin, Secretary of State, designed by Messrs. Keatinge & Ball, has been selected without alteration.

Five-dollar note, with the head of the Secretary of the Treasury (as appears in Mr. Dunn's design), has been composed from designs furnished by Messrs. Keatinge & Ball and Mr. Dunn, as follows: The lettering of the note as designed by Mr. Dunn; the medallion with the figure "5" to be put on the upper corner over the head of the Secretary of the Treasury; on the left end of the note heavy machine-work of the pattern of that exhibited upon the note of Keatinge & Ball to be extended to the top of the note, with the word "five" printed as in the 1's, 2's, and 5's of Messrs. Keatinge & Ball; with a view of the Capitol at Richmond, enlarged, from the drawing of Mr. Dunn, as a centre vignette.

Ten-dollar note, with the head of Mr. Hunter, of Virginia, and Capitol of South Carolina, as designed by Mr. Dunn. In fact we take Mr. Dunn's design, with the following alterations: One of the medallion "X's"—a design of Messrs. Keatinge & Ball—to be put in the right-hand upper corner, over the head of Mr. Hunter; the machine-work on the left-hand end of the "ten" of Messrs. Keatinge & Ball to be put on the left-hand of the ten selected, with the word "ten" printed as in the "ten note" of Messrs. Keatinge & Ball. The likeness of Mr. Hunter, as in Mr. Dunn's note, to be preserved.

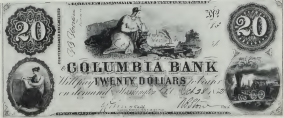

Twenty-dollar note, with the head of Mr. Stephens, the Vice-President, in lower right-hand corner, without scroll; one of the "XX medallions" to be put in the upper right-hand corner (without the scroll), over the head of Mr. Stephens; the left-hand end of the note to be ornamented with machine-work of the pattern now in the lower left-hand corner, to be extended to the top word "twenty," printed as in the other notes of Messrs. Keatinge & Ball, with a view of the State-House at Nashville, as represented by the drawing of Mr. Dunn (for a centre vignette), to be enlarged to suit the space allowed in design of Messrs. Keatinge & Ball.

The details of the notes to be left to Mr. Keatinge, according to the instructions of the Secretary of the Treasury.

The machine-work for the back of the notes is to be left also to Mr. Keatinge, with the understanding that he is to get up a different back for each denominational words "One Dollar," "Two Dollars," "Five Dollars," &c., printed twice, in letters of proper size, so as to cross each other on the back of the note.

From the difficulty of obtaining coloring matter, so as to have all the notes alike, we would recommend that the back of the l's and 2's be printed in red; the back of the 5's, 10's, and 20's (circulating bills) in green; the interest 100's now used to have the "hundred" on the face left out, and the back in green, with the words "interest hundred" printed straight across the back from left to right; the circulating 50's and 100's to have the words "fifty dollars" and "hundred dollars" straight across the back.

We would further report, without going into details now, that we consider it perfectly practicable to make transfers in the Government establishment, and that Mr. McGown, with a part or the whole of the force now on the Government supply, will be able to furnish the tranfers necessary to all the lithographic establishments.

Very respectfully,

JOS. DANIEL POPE

S. G. JAMISON

Here too, some commentary and explanation is clearly necessary as the designs proposed and forwarded to the Secretary both as regards the face and the backs were significantly altered, if not completely discarded before the notes reached the form as issued. An important point is that the $1 note used a portrait of Senator Clement C. Clay of Alabama, rather than Senator Yancy. This substitution was politically, not artistically motivated. Yancy had become an opponent of President Davis and Secretary Memminger was not about to honor a man on the outs with his chief. While there is no correspondence to confirm this interpretation, the effort to change the design of the $100 note in November 1862, after Secretary of War Randolph had resigned in a huff because of what he felt was excessive Presidential meddling in the affairs of his Department, together with a failure to consult before decisions were made, allows us to infer such a substitution. For, on that occasion, Memminger hurriedly wrote asking for the design to be changed, but as the only suitable substitute from a size standpoint was a portrait of Patrick Henry, which was available in the North, the decision was made to stick to the original vignette and the situation had to be explained to the President. Evidently Davis did not insist on a change, and Randolph was thus honored even after his abrupt resignation.

Another key point was in the matter of the back tints. The proposed design for the $1, $2 and $5 notes to be printed in red, was discarded, the back of the $5 note was printed in blue, as was originally planned only for the $20 and the $10 bills. The lower denomination notes in fact received no backs at all. The reason for this change was twofold. First, there was not enough ink available and second, another printing, with its attendant delays was not desired. Moreover, the Government had discovered that they could have pink paper manufactured in the South which would provide the color without the time delays that a second printing entailed.

Quite clearly, despite the competition of others, there were only two engravers in the Confederacy capable of doing work up to the standard expected by the committee and of the two (Keatinge and Dunn), to judge by the work of each that was accepted, Keatinge was clearly the superior. It is true that the Treasury had to make do with lithography, rather than engraved work, but a comparison of the early $20 bills done by the Scottish lithographers with the engraving work done by Keatinge shows such a high quality level of reproduction that the difference was not sufficient to justify the extra work and ink in doing this work the more elaborate way. Indeed, Secretary Memminger for a long time thought that the backs of the $ 100 and $50 notes were engraved, whereas, with the exeption of the earlier issues and those made from leftover plates, all are lithographs.

This improvement in quality coupled with speedier methods of production cut off counterfeiting on any serious basis until the end of the war and allowed the Government to meet its bills more effectively for another year. Then, confronted with a demand beyond their productive capacity coupled with the demands imposed upon them by a massive new funding program, the system broke down and the Treasury fell hopelessly behind. The fault for this lay more with a Congress which failed to impose taxes to check the inflation than with the printers. And if the printers were not as successful as might have been desired, they still did quite well vis-à-vis the North with all its resources, which itself was often a month in arrears on its obligations.

| 1 |

Raphael P. Thian, ed., Correspondence with the Treasury Department of the Confederate States of America, 1861-1865, Appendix, Part 5, 1861-62 (Washington, 1884), pp. 588-89.

|

| 2 |

Pope to Memminger, August 18, 1862, in Thian, Correspondence, pp. 596-98.

|

| 3 |

Dunn to Pope, August 19, 1862, in Thian, Correspondence, pp. 599-601.

|

| 4 |

Type references are to Grover C. Criswell, Confederate and Southern States Currency, 2nd ed. (Citra, FL, 1976).

|

| 5 |

Douglas B. Ball, "Confederate Currency Derived from Banknote Plates," The Numismatist 1972, pp. 339-52.

|

Coinage of the Americas Conference at The American Numismatic Society, New York City

© The American Numismatic Society, 1985

Two great economic truths were swiftly recognized in the South following Secession: first, the newly formed central government could not function, much less wage war, without money; and second, the chartering of banks under different codes within the various southern states made necessary some sort of voluntary system under which they could work together across state lines in support of national and regional economic requirements. Accordingly, urged on by the Tennessee Legislature, and doubtless encouraged by the new central government in Richmond, some of the major southern banks sent delegates to an initial Bank Convention in Atlanta at the beginning of June 1861. Resolutions were passed by that Convention on June 3, 1861, recommending that all southern banks receive and pay out Treasury notes of the CSA government; that they advance the government money against deposit of high denomination Treasury notes or stocks and bonds; that the railroad companies be urged to accept Treasury notes for fares and freight bills; that the legislatures of the various states pass measures to allow Treasury notes to be used for the payment of taxes; and a variety of related measures. The Convention, headed by Gazaway Bugg Lamar of Savannah, Georgia, then adjourned to meet again on July 24 in Richmond.

The Convention reassembled on the appointed date with a substantial increase both in the number of delegates attending and in the number of banks represented; Lamar was again in the Chair. This second meeting of the Bank Convention lasted through July 26 and produced numerous resolutions reinforcing those of the earlier meeting and adding further details to the suggestions made at that time. Following opening services and the reading of the minutes of the previous meeting, President Lamar informed the delegates that he had been in contact with Memminger, Secretary of the Treasury of the CSA, and had learned from him that, during the adjournment of the Convention in June and July, Memminger had received letters from various CSA banks agreeing in general with the proposals initially set forth.

The Convention then acted swiftly on a series of motions and resolutions: hearty approval of the government's action in prosecuting the war against the United States; general agreement that southern resources were more than adequate to handle a war, and that the delegates to the Convention would contribute their aid to render those resources available to the public; that it was the duty of banks, capitalists, and property holders to provide monetary and other support to the central government during the war; and that a committee of one delegate per state be set up to receive and pre- sent resolutions to the Convention as a whole. Having passed these resolutions, the Convention adjourned until July 25.

By the time of the next meeting on July 25, further delegates had arrived; these were duly introduced to the Convention and took their seats. Ramsey, President of the Bank of Tennessee branch at Knoxville, then moved to invite Secretary Memminger to participate in the Convention; this resolution passed promptly and a delegation was selected to present the invitation. Two major motions were passed on to the Committee on Business: one, that banks would receive and pay out the notes of all other banks in the CSA during the war, as designated by the banks then represented in the Convention from those states then represented; and the other the establishment of a committee to explore the expediency of, and necessary measures for, engraving and printing bank notes and manufacturing bank note paper within the CSA.

By the time these measures had been dealt with, the delegation reported back that it had extended the Convention's invitation to Secretary Memminger and that he was then present in the hall. Upon being presented to the Convention by President Lamar, Memminger thanked the delegates for their support of the government and offered some suggestions for their consideration. Following Memminger's talk, the Convention considered a series of other resolutions which, after discussion, were referred to committee: one proposed that, since many farmers and planters had voluntarily subscribed a portion of their forthcoming crops of cotton and other produce to aid the government, the banks should advance such farmers and planters the sums they might need prior to harvest, such loans to be repaid to the banks when the crops were sold; another proposed that all banks in the CSA would receive and pay out each other's notes and also all CSA notes from $5 to $100, the balances due between banks to be settled in CSA notes; and a third recommending that banks agreeing to the proposals of the Convention should limit the circulation of their own notes so as not to exceed their actual capital.

On the recommendation of Secretary Memminger, the Committee on Business was asked to consider, and report to the Convention upon, the nature of post notes which they felt it would be advisable for the Government to issue; what amount of such notes might safely be placed in circulation; and whether or not it would seem advisable to control, through advances on produce, the crops of cotton and other non-perishables in case the Union blockade was maintained. Another of the delegates then proposed a resolution to the effect that the Convention recommended the issue of Treasury notes, most of which should bear 5 percent interest per year; and further, as a separate resolution, that any attempt by the Convention at that date to interfere with existing regulations on the receiving and paying out of notes, with the exception of the agreement to handle the Treasury notes, would be highly inadvisable. This latter point was basically a States' Rights platform introduced into a Convention whose very meeting proclaimed the necessity of central operations extending across state boundaries if the Confederacy were to be able to carry on the war successfully. It was to return to haunt them very shortly.

This rapid growth in the number of matters referred to the Committee on Business led to a motion to increase the number of members of that committee so that it might be able to complete its tasks within some reasonable time period; this passed, and the President added seven more members to it. The Convention then adjourned for the day.

When the Convention reopened on the morning of July 26, a lengthy series of resolutions was proposed to deal with one of the most difficult problems facing the Convention members: the constitutional prohibition in the State of Louisiana against suspension of specie payments and the issuance of paper notes instead, which was basically what was being proposed as general policy for the delegate banks in accepting and paying out the proposed CSA Treasury notes. The resolutions proposed urged that the Louisiana banks take steps as rapidly as possible to assemble, if necessary, a state convention to nullify or revoke the constitutional provision in question; that they press for this vigorously; that the Governor of Louisiana be requested to cooperate in the matter; and that the Secretary of the Convention should forward the entire proceedings of the Bank Convention to the Louisiana Governor and to all the Louisiana banks. At the request of the proposer, these resolutions were tabled temporarily.

The Standing Committee then proposed that all banks in the CSA should make arrangements with the major banks in the cities to receive notes of those banks in payment and on deposit, and that those banks so doing should post public notice of their arrangements so that soldiers would not be subjected to discounts on their pay through dealing with banks which were not parties to such arrangements. This was adopted. The Committee also recommended acceptance of the earlier motion for the banks to make advances to planters who had pledged part of their future crops to the aid of the government, but that other proposals regarding control of crops be postponed until a later meeting of the Convention when the situation might have stabilized or changed significantly. This was also accepted. After a few other motions had been handled—most of them being referred to the Committee on Business—the President read a letter from the two delegates from the Crescent City Bank in Louisiana (the only bank in that State which had sent delegates) politely requesting that their names be removed from the list of delegates since they had found out that no other banks from Louisiana were going to be represented at the Convention and thus felt themselves in a rather awkward position. The Convention then adjourned until late afternoon.

The evening session on July 26 marked the conclusion of this second meeting of the Bank Convention. It was largely occupied with the presentation of the recommendations of the Committee on Business. These recommendations, embodied in a formal report, included the opinion that it would be safe for the CSA Government to issue "at least one hundred millions of dollars, in addition to the notes already authorized by law"1 as the members of the Committee felt certain that such notes would be willingly accepted by the citizens and the banks and would soon become the currency of the country. A further resolution they proposed modified one made earlier at the first Convention by stating that banks represented at this session of the Convention would receive and pay out such Treasury notes as "may be issued by the Government," thus accepting in advance all future note issues. They also urged all banks which were not represented at the Convention to adopt a similar resolution and send it to Secretary Memminger.

Since it was clearly the intention of the government that these Treasury notes serve the function of a currency system, the committee recommended that all notes of a given issue bear the same date of issue and carry the same rate of interest, to reduce confusion and difficulty on the part of tellers and others in handling them and calculating the interest due on the individual notes. They recommended an interest rate of 2 cents per day per $ 100, which worked out to 7.3 percent per annum; that the notes be redeemable in three years or less, at the option of the government, and that they be convertible at the choice of the holder into 8 percent stocks or bonds; also, that they be receivable for all public dues except the cotton export tax. They also recommended that notes from $5 to $20 should not bear interest as they would function as the basic notes within the currency system.

A few other items remained to be handled after acceptance of the committee's report: a delegation was sent to President Davis to see when he might be able to meet the delegates briefly; assorted stan- ding committees were composed to prepare for a future meeting of the Convention in October; James Rose of South Carolina succeeded Lamar as President; and a final resolution of importance to bank and Treasury note students was passed, calling the attention of enterprising persons to the need for an establishment in the CSA to produce bank note paper and engraving plates and for actually producing the needed notes. With notice from the delegation that CSA President Davis would receive the Convention delegates at 9 o'clock that evening, the Bank Convention adjourned. It had accomplished perhaps more than it had expected, but many problems remained, the majority of them having to do with the States' Rights factor—especially in Louisiana and western Alabama—and the complications of the Union blockade and eventual staggering inflation.

Perhaps the most important factor left unresolved was the Louisiana situation: since Louisiana banks were forbidden to suspend specie payments and use paper notes instead, they could not cooperate in the general bank resolve across the South to receive and pay out the CSA Treasury notes. The matter was further complicated by the close connections between Louisiana finances and those of southern and western Alabama, including Mobile; if the Louisiana banks had to operate on a specie basis, then so did the nearby Alabama banks for the practical reason of staying in business. Since specie was virtually unobtainable in quantity anywhere in the South after 1861, handling of payment for any government project was very difficult. In the long run, the inability of the banks and the Government to make payments in specie in Louisiana and adjacent areas meant that work on the vital ironclad gunboats being built in New Orleans was slowed by the difficulty of obtaining parts and also by massive labor disputes. Those gunboats were still incomplete when the Union fleet attacked up the Mississippi and captured New Orleans (which they would have had great difficulty doing if the boats had been ready for their approach). The loss of New Orleans and control of the lower Mississippi eventually cost the South the war, so we may say with justification that the situation that led the Louisiana delegates to withdraw from the Richmond Convention was ultimately a contributing cause of the defeat of the CSA itself.

A complete list of the delegates to the Bank Convention in Richmond has survived; and is included at the end of this article. Altogether, 51 banks from 7 states (including, initially, Louisiana) were represented, most of them sending the President of the bank. Some sent two representatives, and five of the banks sent three delegates. The smallest delegations included Louisiana (two delegates from a single bank) and Alabama (three delegates representing the Central Bank); in both cases the Louisiana specie problem was involved, as discussed earlier. The other states involved were Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia (which, of course, was hosting the meeting). Had anything (such as a Union raid in strength) happened to the Convention, the Southern banking community would have been decimated at its highest levels.

We know some details concerning a few of these delegates. For example, the Cashier of the Planters and Mechanics Bank in South Carolina was Clement Hoffman Stevens, born in Norwich, Connecticut, in 1821. At the start of the Civil War he was placed in charge of building the fortifications and armored battery on Morris Island; in 1862 he was commissioned Colonel of the 24th South Carolina Infantry Regiment, and was promoted to Brigadier General in 1864. At the end of July of that year, he was killed in the battle of Peach Tree Creek during the Atlanta campaign. The President of the Knoxville branch of the Bank of Tennessee was Dr. James Gettys McGready Ramsey, born in Knoxville in 1797 and doubtless one of the major forces in getting the Tennessee Legislature to urge the convening of a banking convention. He practiced medicine in Knoxville from 1820 on, and was a Director of the Louisville, Cincinnati and Charleston Railroad. He was also President of the Knoxville branch of the Southwestern Railroad Bank (whose President, James Rose, succeeded Lamar as head of the Bank Convention). Ramsey served as President of the Tennessee Historical Society from 1874 until 1884; he died in Knoxville in April of that year.

We have seen something of Lamar's role as President of the Bank Convention during its first two meetings in Atlanta and Richmond. In addition to serving as President, he represented two Georgia banks: the Bank of Commerce, Savannah, of which he was President, and the Bank of Columbus; he also had a financial interest in the Mechanics Bank of Augusta, of which his brother was Cashier. He was born in Georgia in 1798. In 1834 he built the steamer John Randolph, the first iron steamboat in American waters, and was a founder in the next year of the Iron Steamboat Company of Augusta, Georgia, operating on the Savannah River. From 1845 until 1861, he was President of the Bank of the Republic in New York City, and he represented CSA interests there as agent during 1860-61, purchasing and shipping south large amounts of arms and ammunition and becoming involved in the attempt to have bank note plates engraved in New York City for the CSA. During the Civil War he served as head of blockade running operations for the CSA; when the famous Stonewall Jackson memorial medals, which had been made in Europe, were run through the blockade in 1864 and reached Savannah, it was in one of Lamar's warehouses that they were buried to keep the Union forces from finding them.

These three interesting characters, who were delegates to the Bank Convention in Richmond, were also signers of bank notes for their own banks in their regular capacity within those organizations. We currently know, from actual observation, of 38 delegates who signed circulating notes from 37 represented banks, and there are probably others on the list of whom we have not yet seen a signed note. We have seen one of the interconnections between delegates in the case of Ramsey and Rose. We also have some reason to believe that Lamar (running the steamboat line on the Savannah River as well as the Bank of Commerce) was connected by marriage with James Rose of the Southwestern Railroad Bank in South Carolina, and that both of these men were connected with J.W. Davies of the Georgia Railroad and Banking Company by marriage, thus establishing a river and rail network covering much of the South and handling a very profitable volume of goods. Doubtless there were similar connections between others of the major financial figures in the relatively small and compact southern banking community. We also, as it happens, know the name of Lamar's opposite number in 1861, the man who served as Chairman of the banker's commission which agreed to cover the first Federal War Loan: Moses Taylor, President of the City Bank in NYC from 1855 on, Controller of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad from 1857 on, Treasurer of the first Atlantic cable venture, President of the Lackawanna Coal and Iron Company, and later Treasurer of the Marquette, Houghton and Ontonagon Railroad in Michigan.

Members of the southern banking community cease to be just signatures on obsolete notes when we can observe tham at work in other areas, and serving as delegates to the 1861 Convention. We can begin to realize what a small group of men were in charge of the major share of the wealth of the South, and how vital their cooperation was to the new CSA government; from their roles in the Convention, and the resolutions they proposed and passed, we can see how vitally interested they were in the success of that new government. It all adds a new dimension to obsolete note collecting, and an increased pleasure.

ALABAMA

Central Bank of Alabama: Wm. Knox (Pres.),2 Chas. T. Pollard, J. Whiting.

GEORGIA

Bank of Commerce, Savannah: G.B. Lamar (Pres.).

Bank of Columbus: G.B. Lamar.

Bank of Middle Georgia: W.B. Johnston.

Merchants and Mechanics Bank, Macon: W.B. Johnston.

Planters Bank of the State: R.R. Cuyler.

Central RR and Banking Co. of Georgia: R.R. Cuyler.

Mechanics Bank of Augusta: Thos. S. Metcalf (Pres.).

City Bank, Augusta: Thos. Barrett.

Geeorgia RR and Banking Co.: J.W. Davies.

LOUISIANA

Crescent City Bank: W.C. Tompkins, J.O. Nixon.

North Carolina

Bank of the State of N.C.: G.W. Mordecai.

Bank of Cape Fear: W.A. Wright.

Farmers Bank of N.C.: W.A. Caldwell (Cash.).

Bank of Yanceyville: Thos. D. Johnston (Pres., earlier Cash.).

Bank of Clarendon: John D. Williams (Pres.).

Commercial Bank of Wilmington: O.G. Parsley (Pres.).

Bank of Washington: James E. Hoyt (Pres.).

Miners & Planters Bank: A.T. Davidson (Pres.).

Bank of Fayetteville: W.G. Broadfoot (Pres., earlier Cash.).

Bank of Lexington: B.A. Kittrell (Pres.).

Bank of Lexington, Graham Branch: E.F. Watson.

Bank of Wadesborough: H.B. Hammond (Pres., earlier Cash.).

SOUTH CAROLINA

Bank of the State of S.C.: C.M. Furman , C.V. Chamberlain (Pres.).

Bank of South Carolina: George B. Reid (Pres., earlier Cash.).

State Bank: Wm. C. Bee, Robert Mure, G.M. Coffin.

Union Bank of S.C.: W.B. Smith (Pres.).

Planters & Mechanics Bank: J.J. McCarter, C.H. Stevens (Cash.), C. T. Mitchell

Bank of Charleston: J.K. Sass (Pres.), George A. Trenholm.

Southwestern RR Bank: James Rose (Pres.), J.G. Holmes.

Farmers & Exchange Bank: John S. Davies (Pres.).

Peoples Bank: D.L. McKay, Jos. S. Gibbs (Pres.).

Merchants Bank of S.C. at Cheraw: Allan McFarlan.

Bank of Georgetown: J.G. Henning (Pres.).

Bank of Chester: George S. Cameron (Pres.).

Exchange Bank: John Caldwell.

Bank of Hamburg: J. W. Stokes (Pres.), Wm. Gregg.

Tennessee

Bank of Tennessee: G.C. Torbett.

Bank of Tennessee, Memphis Branch: Jos. Lenow.

Bank of Tennessee, Knoxville Branch: J.G.M. Ramsey (Pres.).

Bank of West Tennessee: T.A. Nelson (Pres.).

Bank of Memphis: M.J. Wicks.

Planters Bank, Memphis Branch: D.A. Shepherd.

Farmers Bank of Virginia: W.H. Macfarlane (Pres.).

Bank of Virginia: James Caskie (Pres.), A.T. Harris, J.L. Bacon.

Exchange Bank: L.W. Glazebrook, W.P. Strother.

Bank of the Commonwealth: L. Nunnally (Pres.), J.B. Morton , J.A. Jones.

Merchants Bank of Virginia: C.R. Slaughter (Pres.).

The Danville Bank: W.T. Sutherlin (Pres.).

Bank of Richmond: Alexander Warwick (Pres.).

Traders Bank of Richmond: A. Johnson , Hector Davis, E. Denton.

| 1 |

The Proceedings of the Richmond Convention are published, most conveniently, in "Proceedings of the Bank Convention of the

Confederate States," The Essay-Proof Journal 102 (1969), pp. 76-83, with illustration of the original title page on p. 76.

|

| 2 |

Delegates who signed issued notes are indicated in italics.An Historian's View of the State Bank Notes: A Mirror of Life in

the Early Republic

|

Coinage of the Americas Conference at The American Numismatic Society, New York City

© The American Numismatic Society, 1985

It is an auspicious opportunity when we come in direct contact with contemporary artifacts; in our instance, numismatic items serve as such first hand documents, defeating the contention of many historians that numismatics is not easily approachable by the historic researcher. Coins and money in general can be an excellent inspiration to the historian, they being after all the nervus rerum gerendarum, the means which put in motion the entire life of the past: its politics; its wars; its riches; its arts. But in order to reach valid historical conclusions, we need to subject coins to a complex research program. In our case the state and private bank notes which were produced during the first half of the nineteenth century speak in good part for themselves. A kaleidoscope mirroring the entire spectrum of people's lives, activities and feelings unfolds in an unbelievable richness and never-ending succession of miniature paintings.

It has happened to me only twice in my numismatic career that I have been astounded by a numismatic history book illustrated by the very people of that period: one is the series of Roman Republican denarii, depicting in hundreds of coin images the mythology and history of that remote period, and then again the stupendous series of vignettes which embellish the so-called "obsolete" notes of the United States. Departing from the very official, rigid and terse emblematic appearance of currency notes in general, bankers of that period entered into a frenzied competition to outdo each other by rendering their notes varied, attractive and meaningful.

There might have been a similarity between the moneyers of the Roman Republic and the bankers of the early United States: both were avidly seeking to capture the interest of the public. The Roman moneyers tried to further their political careers—their cursus honorum—the U.S. bankers attempted to gain the support of the public at large in order to increase their business. I am tempted to ascribe to these ambitions the basic incentive to create a medium of circulation which varied drastically from the general aspect of currency. The Roman moneyers had to extoll the deeds of their ancestors, which could not be shown only by a symbolic figure but required a representation of a more complex scene. The American bankers produced a similar storybook on their currencies. They were the creators of a capital which was at the base of the growth of the new country. Banking was a free enterprise and bankers were therefore in fierce competition with each other. It is interesting to remark that the Roman Republican denarii were created in a period of intense growth as were the state and private U.S. bank notes. It was the period of the introduction of mechanization, of the locomotive, of the steamship, of budding industrialization, and, at the same time, of the development of the backbone of the national economy—farming and cattle-raising. People worked hard to tame the new lands and transform them into a rich productive country. It was, in a different form, the El Dorado of which settlers of the western world had dreamed so often. People were conscious and proud of their achievements, and nobody was more so than the banker who was at the root of all these achievements. He wanted the world to know what the people had created, and at the same time, entice them to do more. Why design posters or write brochures telling about your accomplishments when you can put little "posters," illustrated with the most varied scenes, into the hands of everybody? It was one of the most ingenious advertising machines ever envisioned.

These were the psychological motives to create this most unusual kind of currency. In addition, bankers could count on a tradition of art appreciation in the country. From studies of the seventeenth century engravings and wood-cuts in the Colonies, we gain the impression that homes were often decorated with various prints, as a traveler remarked in Williamsburg "that I almost fancied myself in...some...elegant print shop."1 The description of prints of the eighteenth century indicate a great variety of subjects—nature and city views, Indian portraits together with so-called "heads," authentic and imaginary portraits of contemporaries. The public was used to seeing prints even with a classical and historical content, collect them and hang them in their homes. Therefore to see their money decorated with similar engravings would not seem unusual to them.

As to the artistic value of these vignettes, we know who created them; the printing companies seldom failed to put their names in fairly visible locations on these notes. There is a long roster of names of printing firms, ending with the exceptionally active American Bank Note Company. We even know in some instances the engravers of the vignettes, but we ought to know more about the source of inspiration of those artists—an enormously vast and complicated research field. I tried to cut the Gordian knot by asking myself about the motive in selecting certain themes or subjects. We know that special sample books were prepared by the printing companies which facilitated the choice of the bankers. I see in their preference for particular themes the key to the mentality which dominated not only the business world of those decades but which also reflected, to a certain extent, the way of thinking and feeling of an entire nation.

My point of departure in examining these design elements is the assumption that no matter what the personal tastes or motives of the bankers were, they would not have continued to impose a selection and a style which would have been displeasing to the majority of their customers. Sinclair Hitchings stated in an article on the graphic arts in colonial New England that: "The graphic art... produced in New England in the seventeenth century was the result of what people in the colonies needed, what they had time for, and that for which they were willing to spend money."2 I am certain that not everybody felt the same way about the selection of themes or of their rendition, but the large majority must have enjoyed it; otherwise the richly illustrated currencies could not have survived for half a century.

As an historian I have always been interested in the way people thought or felt during the various periods of history. We know from our own experience how much the mentality of our own pre- and postwar generations varied, and how difficult it is for them to understand each other. Therefore, I find it invaluable to discover a window which permits us to look directly into the way of thinking of generations removed by more than 100 years from our own world. Of course any historian has to ask how authentic, how true to real life are these myriad pictures? The answer cannot be straightforward; it has to be subjected to rigorous scrutiny in each case. But as a general introductory statement I feel safe in asserting that they render a true picture of the artistic taste of the period. As to the inspiration for many vignettes, I am touching again upon a large undisclosed chapter which could reveal fascinating aspects. Art and art objects were not unknown to the American public in the early 1800s. Some of the famous collectors and artists who traveled and studied abroad were perfectly informed about the great art trends in Europe, which certainly have served as inspiration to many engravers, disseminating this aristocratic hobby among the masses. I would like to accentuate only the fact that special attention should be paid also to the various ethnic groups in the country who might have favored their native art or artists.

Whoever is familiar with the genre paintings of the past century will feel immediately at home with the style of most of the vignettes. We are at the end of the Romantic and Biedermeier period when artists shied away from the harshness of reality, and enveloped everything in a hue of eternal beatitude. The bucolic happiness which some vignettes exude should not be viewed as an intended distortion of reality, but as an expression of the artistic taste of the period which permeated not only the graphic arts, but also literature and poetry. Therefore, when using the vignettes as illustrations of life in the early 1800s, we should be aware that we are often looking through a rose-colored filter, and search for the reality, which is there and unfolds in an almost neverending variety of aspects.

Many vignettes furnish us with a lot of historically valid information and greatly enrich our understanding of the material culture as well as of life in general in the United States 150 years ago. I am afraid that this paper instead of answering questions will actually map out a rather long series of new aspects.

I intend only to sketch out some of the main aspects or categories which I have extracted from the great multitude of subjects. These include: early settlers and historical scenes; the ethnic environment—the Indian and the Black; family life; farming; transportation—trains, ships, bridges, canals; occupations; city views; buildings; monuments; and, not to be overlooked, an endless number of male and female portraits; allegories; mythological scenes, and even saints. There are indeed only a few aspects of human life which have not been touched upon, such as music, sports and religion. Should these omissions induce us to draw some historical conclusions?

Undoubtedly farming and the inventions of the century, the steam engines, dominate uncontested as the main factors in the economy of the time. It should be noted that the subjects of the vignettes are not necessarily tied to the general characteristics of the areas where they were issued, although often there is a logical connection between the place of issue, the name of the bank and the subject of the vignette—cottonpickers are not easily found in New England, neither is whaling in Kentucky. Therefore we can state, within certain limitations, that the vignettes tended to underscore local patriotism and pride.

Interestingly, the number of vignettes referring to historical events is relatively limited, concentrated mostly on the colonization period and the Revolutionary War: Washington's crossing of the Delaware in the cold December of 1776, after a painting by Thomas Sully; the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown, October 1781, after a painting by John Francis Renault;3 Colonel Marion, the "Swamp Fox" inviting a British officer to share his potato and water dinner, after a painting by John B. White;4 and the widely used "Signing of the Declaration of Independence," after John Trumbull's famous painting (fig. 1).5

The patriotic feeling of the country found strong expression in the countless portraits of political figures, George Washington being overwhelmingly acknowledged as the "founder," the "Father of the Country." Examples include the copy after Gilbert Stuart's "Washington on Dorchester Heights,"6 and another vignette characteristic of Washington's apotheosis, with his bust surrounded by three muses of the arts in semi-classical attire (fig. 2).7

Benjamin Franklin follows closely as one of the favorite fathers of the country. David Martin's so-called "Thumb Portrait" is an especially well executed art work.8 From among the hundreds of male portraits of famous or sometimes anonymous national or local personalities, one might note the level of artistic quality in John W. Dodge's portrait of the aging Andrew Jackson,9 or the likeness of Major General Thomas Sumter (1734-1832), Revolutionary soldier, copied after an oil of 1795/6 by Rembrandt Peale.10 Highly interesting is the fact that even famous foreign personalities, such as Napoleon I, or even classical and mythological figures such as Archimedes, Cincinnatus or Atlas found their place on American bank notes. Due somewhat to the public's select knowledge of foreign literature and history, but rather more to ethnic pride are the somewhat primitively designed portraits of German literary figures, such as Johann Wolfgang Goethe 11 and Johann Gottlieb Klopstock, represented by the Northampton Bank in Germanic Pennsylvania of the 1830s.

The female portraits constitute one of the most puzzling chapters in the history of the graphic arts of the American currency. In addition to a few well known figures such as Martha Washington,12 Dolly Madison, Jenny Lind, and even Josephine Beauharnais, practically dozens of lovely young ladies are represented on paper notes (fig. 3).13 We cannot escape the impression of romanticized valentine card figures, however incongruous that is in the context of the forbidding dignity of a business document such as a bank note. Many of the lovely ladies must have been the beauty queens of those days or relatives of leading local personalities, who have thus entered anonymously onto the roster of important figures of the early 1800s. Many vignettes do have the pronounced character of an authentic portrait,14 but to search for their identity is a tremendous job which could be quite rewarding, but must be undertaken with great patience. They all express the general romantic admiration for serenity and aesthetic perfection which permeates practically every scene represented by the artists of those days.

Family life is idyllic and beautiful; children are well behaved and eager to learn,15 and life on the farm with all its chores seems leisurely and enjoyable (fig. 4); 16 milkmaids look like fashion models posing in front of a tranquil landscape.17 No matter how distorted these representations might be, considering the hard life of the farmer and the worker who had to bear the brunt of the tremendous effort to build the country, we cannot dismiss the importance of some vignettes giving us a more realistic picture of the material culture and ambience of the period with their tools and farm utensils. Examples include: a grain cradle;18 one of the early mechanical reapers, most likely Hussey's reaping machine of the 1830s, not McCormick's famous new invention, since it has a hand rake (fig. 5); 19 one vignette depicts a complex of three agricultural machines—harrow, hay thrower, and another type of mechanized weeder.20 We are told about the quality of the crops by reference to man-high corn; the importance of the cotton industry;21 haymaking; the making of turpentine (fig.6).22 Of interest and significance is the attention given to farm animals,23 such as the horse, sheep, pig, and to scenes dealing with the cattle24 and meat industry.25 On one particular note there is even a hog slaughtering scene (fig. 7).26 Somehow these scenes bring to mind Sandburg and stories of Western "butchers of the world," the cattleman and the sheep rancher.

A country which was rapidly expanding and developing in every way had to show its pride in the industrious people who accomplished the American miracle. Therefore, many occupations are represented on bank notes, from lumberjacks chopping trees,27 and men loading boards, to masons and stone masons, cobblers28 and surveyors (fig. 8).29 The sailor also figures prominently in these notes, generally depicted as a happy young man eager to see the world.30 Interesting is the representation of two occupations—that of an alchemist31 and of a drummerboy.

Fascinating are the vignettes depicting one of the most lucrative but most hazardous occupations, that of whaling, which spellbound the world with its haunting stories and lured men far into endless waters. One vignette, "attacking a right whale and cutting in," (fig. 9) is a scene copied after a French marine painter, Louis Garneray (1784-1857).32 Women are seen not only on the farm, but also in the sweatshops of early industry, as they can be viewed at looms (fig. 10) 33

The budding industries were certainly the pride of the country, factories with smoke stacks are not rare on notes,34 often representing local industries, such as the Franklin Silk Industry in Franklin, Ohio, or symbolizing banks bearing in their titles names such as Manufacturers, or Mechanics. Scenes depicting men working at a forge, in front of glass melting furnaces,35 or with large machines, can be of great help to industrial historians by giving detailed pictures of tools and of working techniques. Men loading barrels of tobacco point toward another important wealth—the tobacco industry. The mining (mainly coal) industry36 as well as the relatively new industry of oil extraction at Titusville, PA (fig. 11).37 find their place also among the important resources of the country. In short, there doesn't appear to be an industrial advancement that was not depicted on the bank notes.

Transportation was another facet of the country's growth which found an exceptional interest with the public. A notable scene shows a vehicle similar to a Conestoga wagon passing through what appears to be a tollgate (fig. 12).38 This scene on a note issued by the Easton and Wilkesbarre Turnpike Co. in Wilkesbarre, PA, could have taken place along one of the earliest turnpikes in the country, such as the Lancaster Pike which ran from Philadelphia to Lancaster and had tollgates every seven miles. The loading of large bales of cotton and their transportation in carts pulled by three teams of mules can be seen on bank notes issued by southern banks.39 Their ultimate destination was the wharfs, where steamships waited in the background for the cargo brought in by carts and trains.40

The Black makes his appearance in these vignettes either as a cotton picker or as a driver of mule carts and coaches. The so-called Concord coach manufactured in Concord, New Hampshire seems to have been the standard means of transportation for people. One vignette depicts an overland mail coach—Beachey's Line for California (fig. 13),41 another provides a real genre scene—a friendly chat between two blacks and a white man driving a two-wheel cart.42

For water transportation, artists usually depicted barges as well as smaller boats and rafts. Flatboats often can be seen on large waterways. Quite interesting were the shanty boats of hunters and trappers with a hut on top for living on the water (fig. 14).43 Hand in hand with the construction of roads came one of the most important factors in the rapid growth of the country—the development of good waterways. The first attempt to penetrate deeper into the hinterland was to connect the Hudson River with Lake Erie; conceived by Gouverneur Morris, it became a reality under the leadership of the New York City Major and later Governor DeWitt Clinton (1769-1828).44 In 1825 the Erie Canal connected Buffalo on Lake Erie with Albany on the Hudson. This success started a "canal craze or fever," which brought an undreamed expansion and prosperity to the country. The paper notes did not miss this fact. Examples include a boat drawn by horses through a canal in Washington, D. C.,45 or in Wisconsin;46 the James River and Kanawha Canal in Virginia;47 or the Dismal Swamp Canal located at the border of Virginia and North Carolina, connecting the Chesapeake Bay and Albemarle Sound.48 Fascinating is the vignette showing the raising of a boat on a steep incline to a higher level of a canal (fig. 15).49 Bridges varying from arched to suspension were even more often depicted on paper notes, already being shown on notes of 1816 (Bridge Co. of Augusta, Georgia). A very popular vignette used during the 1850s and 1860s is of the bridge over the Susquehanna River at Rockville, near Harrisburg, PA (fig. 16).50

The country seemed to have reached the peak of its mechanization through its trains, which had a slow beginning but once well entrenched took over the country in a storm, helping to conquer the wide spaces of uninhabitated land and tying the Atlantic to the Pacific.

The canal era gave way to the era of trains and the paper notes reflected fully this triumph. No subject was as popular on bank notes as trains. The amazing fact is that we can follow the technical evolution of the train quite well through the vignettes, although in some cases we have to contend with the vivid imagination of the artist. After Peter Cooper proved in 1830 that his locomotive, Tom Thumb was, if not faster than the horse, at least trustworthy of negotiating treacherous curves, the future of the steam powered train was assured. Vignettes of the early 1830s show us the first trains with one or more passenger cars (fig. 17), 51 called omnibus cars, some with coal tenders,52 others with early British engines, carrying some freight cars53 and tenders54 which protected the passengers from possible explosions of the boiler. Later there were trains with a John Bull locomotive, and the number of passenger and freight cars increased. The two designs from John White's book on John Bull's 150th anniversary of its first run on September 15, 1831, show the outline of the locomotive as built in 1831 by Robert Stephenson & Co., as well as its component parts, which correspond in general outlines to the drawings on our vignettes.55 Later the outline of the steam-engine changed; in addition to a sturdier body, it had a balloon smokestack, and a cow-catcher in front.56 Other- vignettes show us scenes in train stations;57 the loading of mer- chandise; people greeting the arrival of the train; and, most interesting, a freight train with many coal carts passing a coal processing factory (fig. 18),58 symbolizing the importance trains had in the development of industry.

Ships were another principal means of transportation. Sailboats,59 sloops, schooners, clipper ships, steamboats,60 and Mississippi and Missouri packets and ferryboats were often depicted on paper notes. At times even the name of the more popular steamboats, such as the "Selma," could be clearly identified on the drawings.61 The artists showed, with a tremendous pride, famous sea battles such as that of Commodore Oliver Perry's victory against the British on Lake Erie in September 1813 in an engraving by R.G. Harrison.62 Even an ironclad cannon boat can be seen in firing position on a bank note of 1861, shortly before the famous battle between the Union's revolutionary ironclad Monitor against the ironsided Merrimack of the Confederacy. The intense water traffic had to be supplied by a booming ship construction industry, of which we find a few interesting scenes starting with notes of the late 1830s (fig. 19).63

Another important historical facet is revealed by many vignettes, i.e. the relations between two ethnical elements who were very much part of the American scene—the American Indian and the Black. Interestingly, the Indian is more often portrayed than the Black, who is usually shown as a natural aggregate of farm life (fig. 20),64 and there appears to be no special preoccupation with the slave/owner relationship between Whites and Blacks; the latter depicted as happy and content with their way of life.65 In this area it is evident that the bank notes do not reveal any concern with the great moral and political issues of the day, slavery versus abolitionism. With the Indian the approach is quite different. The Indians seemed through their frequent portrayals and through their poses to convey a message. Their presence is acknowledged, as well as their reserve. The Indian is often a silent observer from a lonely crag of a strange civilization booming with trains, shops and beautiful buildings (fig. 21).66 He is a hunter;67 he enjoys his family life in the midst of natural grandeur;68 but he does not mingle with the newcomers. Of note is that warlike poses are rarely shown.69 Was this indeed due to the little concern shown to the Indian hostility in a period when bloody encounters raged throughout the country, or was it a rather diplomatic oversight? Do all these scenes denote the general uneasiness of the white man toward the Indian? After all, most of these drawings preceded Custer's bloody end by at least 15 to 20 years. Or can it be that, within the spirit of "Manifest Destiny," the idea that the Continent was the white man's prerogative, meant that the Indian was only a part of its natural grandeur? Touching is a scene, redesigned from a less peaceful drawing, where an Indian squaw points with a conciliatory gesture toward a plow, the symbol of domesticated life (fig. 22).70 Interesting also are some of the Indian princess's pictures,71 including an impressive, idealized portrait of a Madonna-like Indian huntress (fig. 23).72

Having examined the ethnical environment, I would like to pay some attention to the rendition of the physical environment, including a lovely view of a southern cove with beautiful palm trees and cotton plants,73 or the rather sketchy rendition of Niagara Falls.74 The animal world is also fairly well represented; deer, ducks, beavers, even a phoenix bird on a nest, and horses, sometimes beautiful wild horses, inspired by Le Roy's "Black and White Beauties," (fig. 24),75 and, of course, the buffalo, the monarch of the prairies.76 Neither do we miss man's best friend, Fido, the faithful guardian of man's riches,77 and a beautiful dog's head, copied after Edwin Landseer's painting entitled "My Dog," perhaps a Bernese Mountain Dog.78

Moving from the wilderness to the city, we find that bank notes often carry highly interesting urban views, some known, but many still to be identified. It is indeed fascinating to study the details of a street view in Cambridge, MA, in the 1840s,79 or the entrance to Llowellyn Park in Orange, NJ, in 1862.80 From among many vignettes depicting interesting buildings may be noted the very imposing view of the yet to be completed Capitol in Washington, in 1851 (fig. 25);81 also a very interesting drawing of the old Dutch Church, built in 1815 in Albany, NY;82 the state house in Charleston, SC,83 and Jefferson's Monticello.84

After churches the most important buildings were banks, such as the temple-like architecture of the Girard Bank in Philadelphia,85 or the classically inspired Bank of Louisiana in New Orleans (fig.26).86 Boston liked to show the Bunker Hill Monument,87 and Baltimore depicted a slightly differently designed Battle Monument,88 erected in 1825 in commemoration of Baltimore's defense in September 1814.

A special chapter should be devoted to the innumerable allegories, symbolizing every possible virtue and any memorable aspect of government, such as commerce or navigation. Figures such as those of Navigation89 or Freedom and Prosperity (fig. 27) 90 are indeed very graceful and well designed. In no other group of vignettes is the influence of classical antiquity more pronounced than in the selection of mythological and symbolical figures. The grace, attire, and coiffure of these ladies is in the finest classical tradition. They were obviously inspired or copied after classicistic paintings of good vintage as in mythological scenes depicting Neptune (fig. 28),91 or a group of Olympians with Mercury the god of money.92 The figure of Liberty93 is often depicted in various attires,94 and can be often mistaken for Columbia.95

Many of the support figures flanking a coat of arms refer to more up-to-date-looking people, such as workers, farmers, and women with children. Remarkable is the often encountered juxtaposition of Indians and Whites (fig. 29).96 The importance of the Indian element in the country is acknowledged by this prestigious role assigned to them—I know of no vignettes depicting Blacks in similar poses. At the same time, through the separate grouping the artists indicated the special position assigned to the Indian in the country.

Finally, one might consider extraterrestrial figures such as an excellently executed St. George killing the dragon;97 or Santa Claus descending from heaven to bring gifts and happiness (fig. 30).98 I consider this unusual figure as symbolic for the entire group of vienettes. which is indeed a Santa's bag of surprises.

| 1 |

Joan Dolmetsch, "Prints in Colonial America," Prints in and of America to 1850, Winterthur Conference Report 1970 (Charlottesville, 1970), p. 54.

|

| 2 | |

| 3 |

Chesterville, SC, Bank of Chester, $5, 1853.

|

| 4 |

Columbia, SC, State of South Carolina, $5, 1872.

|

| 5 |

Watertown, NY, The Watertown Bank & Loan Company, $10 proof, no date.

|

| 6 |

Reading, PA, The Berks County Bank, $5 proof, no date.

|

| 7 |

New Orleans, LA, Citizens Bank of Lousiana, $100 proof, no date.

|

| 8 |

Augusta, GA, Bank of Augusta, $10, 1837.

|

| 9 |

Macon, GA, Manufacturers Bank, $5, 1862.

|

| 10 |

Columbia, SC, State of South Carolina, $5, 1872.

|

| 11 |

Northampton, PA, Northampton Bank, 10 Taler, 1835.

|

| 12 |

Savannah, GA, The Merchants & Planters Bank of the State of Georgia, $2, 1857.

|

| 13 |

Smethport, PA, The McKean County Bank, $5 proof, 1858.

|

| 14 |